In Nepal’s churches, donated properties are held privately, fueling internal strife. Urgent calls arise for a dedicated law to protect and regulate the assets of all religious institutions.

Man Bahadur Basnet | CIJ Nepal

On 8th November, the weekly Saturday congregation started at Koinonia Samdan Church in Hetaunda. The church’s preacher Vinod then recited a story in which a non-Christian took advantage of a fight between two Christian followers. Vinod was standing in the prayer hall of the 33-year-old church in Pratibha Nagar where he was preaching the message of gaining strength through mutual unity. However, the land of the same church has been divided like private property due to disagreements between the followers. As a church is a place of worship and religious activities of Christians, it seems strange that the lands of many churches all over the country are divided in the private ownership of individuals.

Koinonia Samdan Church in Hetauda.

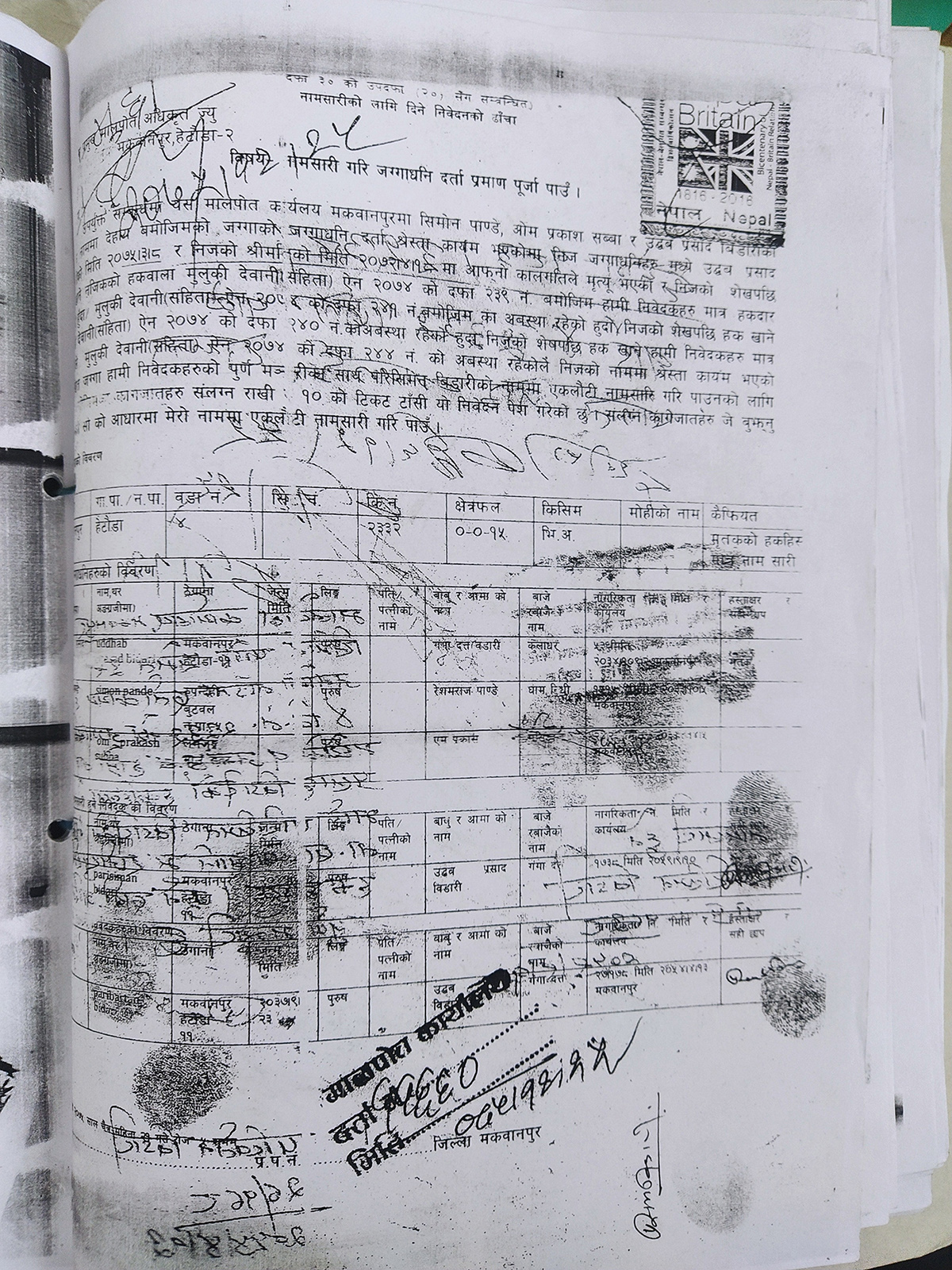

According to the president and pastor of the church, Ramakrishna Pant, Meenakumari Chhetri donated 9 dhur of land for the Koinonia Samdan Church, which was established in 2047. In 2053, the Church sold the land and 15 dhur land was bought in Hetaunda-4. “Since the number of followers was increasing, we sold the land, and a bigger land was bought elsewhere,” remembers Pant. The land was then registered jointly as the property of Uddhav Bidari, then president of the church, Prakash Subba, vice president of National Churches Fellowship of Nepal (NCFN), and Simon Pandey, general secretary. In the minutes of the church board meeting held on 13 Bhadau 2053, it is mentioned that the land will be registered in the name of the three individuals until further legal arrangements are available.

After the death of Uddhav Bidari on Asar 8, 2075, District Land Revenue Office Makwanpur named his son Parisian as the living joint owner of the land. After becoming one of the legal owners, Parisiman approached the court, claiming the church property. “Since my financial situation is extremely poor, I asked them to sell the property and give me my share of the amount. However, as they did not agree to my request, I am forced to appear with a complaint,” he wrote in the complaint letter registered in the district court of Makwanpur in Asar 2076. Parisiman claimed that he would be entitled to the said property because allegedly three individuals including his father equally invested and bought the land.

After the passing of Uddhav Bidari, his son seeks to transfer ownership of Koinonia Samdan Church’s land in Hetauda. The dispute escalates to court as the church’s land is registered under an individual’s name.

However, according to the church board meeting minutes and the NCFN records, the land was purchased to establish the church. Hem Bahadur Thapa, who sold the land, also presented a document that the land was indeed sold for establishing the church. It is also mentioned in the paper that the land was bought with the money collected from the donations and offerings of the followers and various organizations. The ward office also provided financial support to build a church on the land. Ward Chairman Nabin Sigdel says that during his previous tenure (2074 to 2079), the ward provided two lakh rupees to the Samdan Church Building Consumer Committee.

“Just as we support temples, the church is also given a budget for religious activities,” he says. The church establishment submitted the documents of the ward’s financial support to the court to prove that the property was not private.

However, while the case was ongoing, both parties agreed to reconcile outside the court proceedings. “Parisiman asked for Rs 50 lakh. We were ready to give 8 lakh. Finally, a transaction of 13 lakh rupees was made and the reconciliation took place in Chait 2077,” says Pant, the church leader. According to the decision given by the bench of Judge Manoj Shrestha, the agreement was reached after “13 lakh rupees was transacted as a value equal to one-third of the land.”

“What happens when their children start claiming the land in the future? That incident has shaken me to the core. The property bought from the offerings of the believers may end up as private shares!” says Pant. There is a long list of religious leaders like Pant who are worried about the church property going to private individuals.

Pastor Ramakrishna Pant.

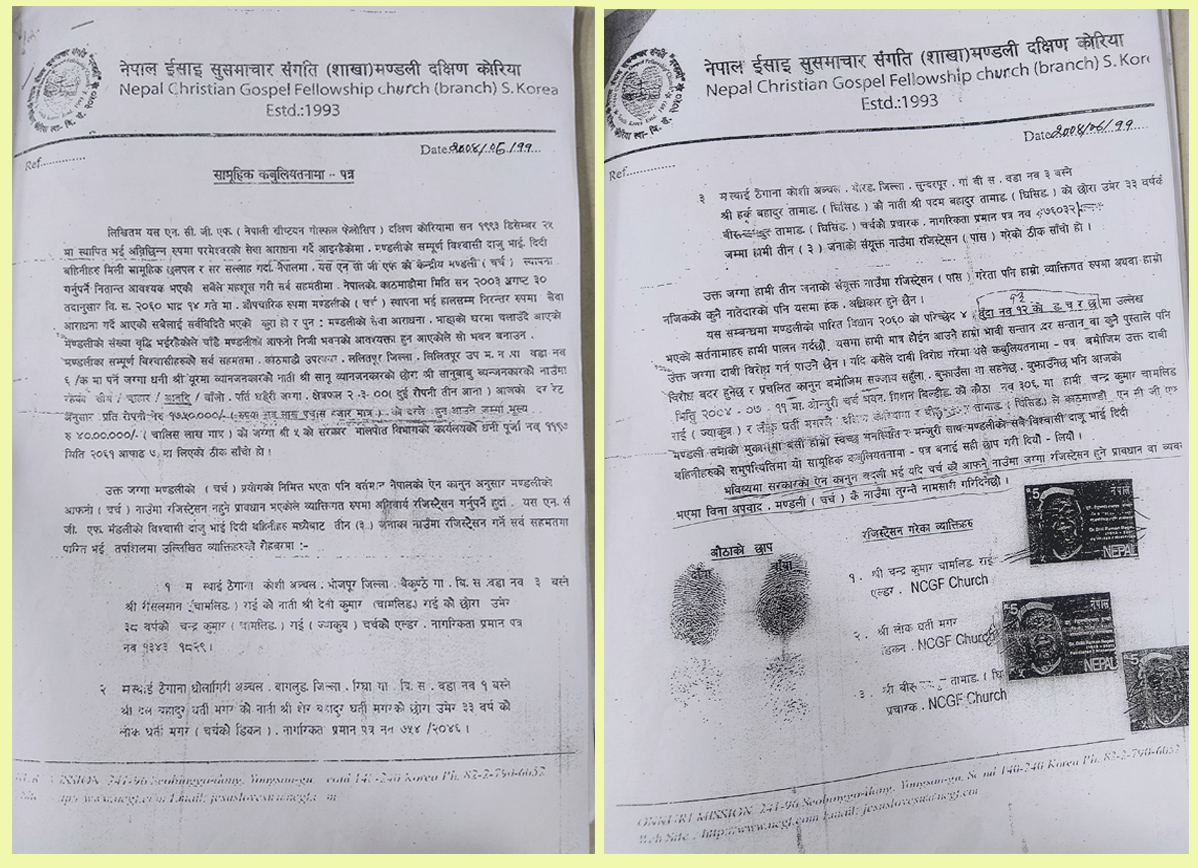

Bir Bahadur Tamang from Morang, Lok Bahadur Gharti Magar from Baglung, and Chandrakumar Rai (Jakub) from Bhojpur established the Nepal Christian Gospel Fellowship (NCGF) Church in South Korea in 2050. As the number of followers increased, they established the church in Nepal in Bhadau in 2060. Initially, the church was run in a rented house, which then moved to its property in Gwarko, Lalitpur after a year. It is revealed from the documents submitted to the court that 2 ropani 3 ana land was purchased for the church in Gwarko for Rs.2 crore 60 lakhs.

The land was registered jointly by the three individuals, Tamang, Ghartimagar, and Rai. It was also mentioned in the mutual agreement that “if the law is changed later, the land will automatically belong to the church and the three individuals’ children, grandchildren and relatives will not be able to claim the land.” However, after seven years, disagreements started between the three of them, which resulted in a chain of claims and counter-claims on the land.

After the property dispute arose, Rai hurriedly registered NCGC by the Organization Registration Act, 2034 on 7 Chait 2068 at the District Administration Office, Lalitpur. The church could have been registered under the same Act earlier as well. “But the churches did not agree to be registered according to this law as they did not want to be equated with non-governmental organizations. Even the administration, upon hearing the name of the church, threw a lot of hurdles in the registration process,” says Chari Bahadur (CB) Gahatraj, president of the Nepal Christian National Federation.

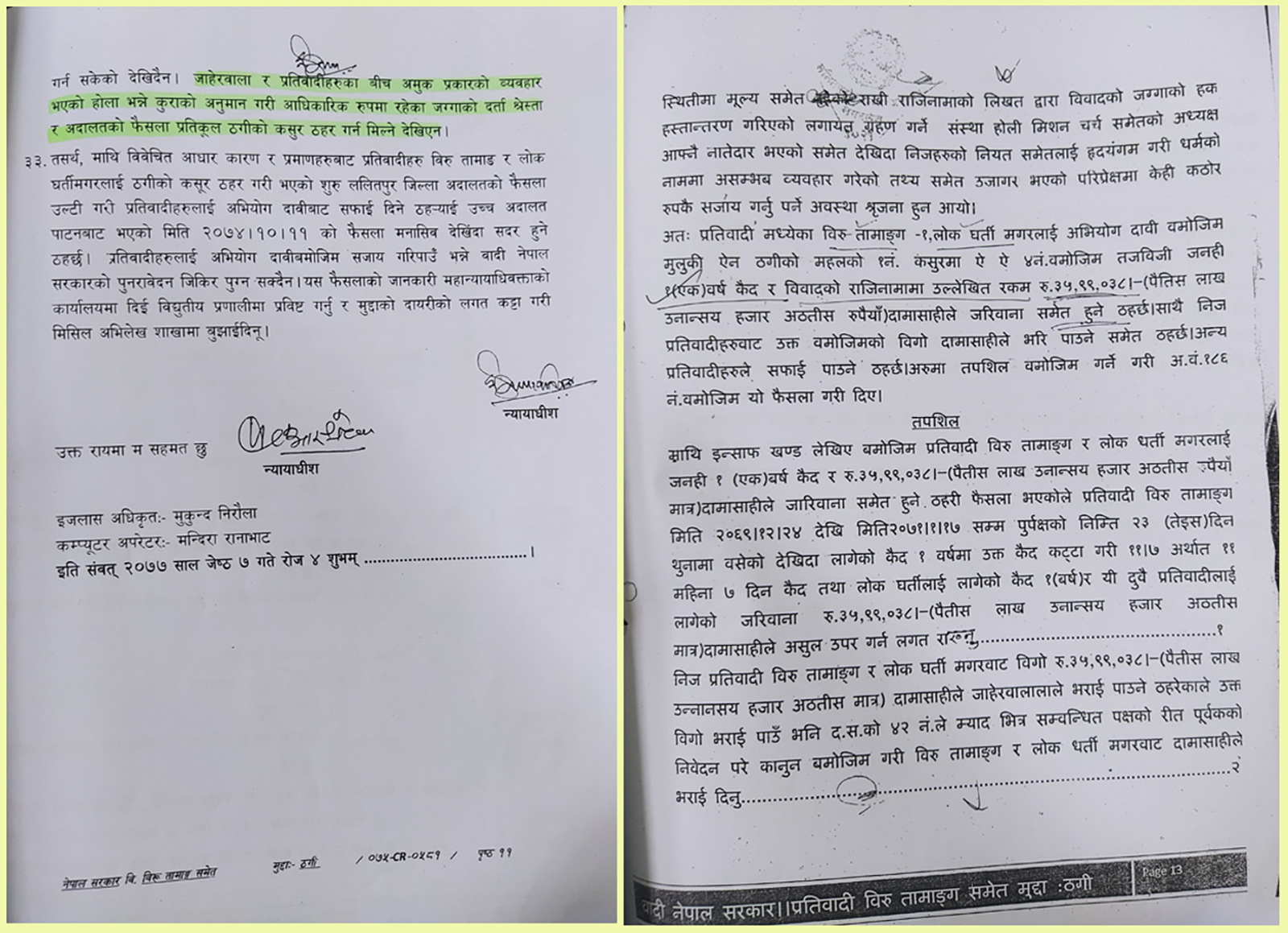

Initially agreed upon, the transfer of land rights to Nepali Christian Gospel Fellowship (Church) faces legal turmoil as the agreement is breached, prompting a Supreme Court intervention over the land dispute.

Twenty-one days after NCGC was duly registered, Tamang and Ghartimagar, two of the landowners, registered another church called Holy Mission Nepal (HMN) in the District Administration Office, Lalitpur. The portion of the land that was registered in the name of the two owners, was then transferred to this new church. After that, the land was registered under the joint ownership of Rai and HMN Church in the records of the land revenue office. But Rai then filed a complaint with the Lalitpur Police saying that Tamang and Ghartimagar cheated by transferring the land portion to the new church when originally the three of them had agreed to buy the land for NCGC. The police investigated the charge of fraud and took the case to the court.

The District Court Lalitpur in Baisakh 2071 found Tamang and Ghartimagar guilty and sentenced them to one-year imprisonment with a fine of Rs.18 lakh each. The bench of Judge Kazi Bahadur Rai decided that the transfer of the land rights to the HMN church, chaired by Tamang and Ghartimagar’s relatives, is a wrongful act under the facade of religion and should be severely punished.

An appeal was filed against this decision in the High Court of Patan. The High Court overturned the decision of the District Court in 2074. After Tamang and Ghartimagar registered their land in the name of HMN Church, both of them filed a separate case of ‘dartafari’ in the District Court of Lalitpur. Filing an application to the court with a demand to divide the previously jointly owned land and register it in the name of a separate person is called a ‘dartafari’ case. Tamang and Ghartimagar were successful as, in Magh 2070, the District Court ruled that their share of the land would be registered separately. Basing its verdict on the District Court’s decision, the High Court explained that since Tamang and Ghartimagar transferred their share of land to the HMN Church by informing the District Court and the District Administration Office, this is not a case of fraud.

Excerpt from Supreme Court and Lalitpur District Court judgments regarding property dispute of Gwarko-based Nepali Christian Gospel Fellowship (Church).

Chandrakumar Rai (Jakub) of NCGC appealed again to the Supreme Court against the decision of the High Court. The Supreme Court upheld the decision of the High Court explaining that the dispute was of a civil nature, and as Rai, Tamang, and Ghartimagar are mentioned in the official records as the land owners, it was not a case of fraud. In the decision made in Jeth 2077, the Supreme Court declared that “the collective confession to register the land in the name of the organization in the future will be invalid.”

This judgment also explained that domestic documents like confessions are not legally recognized. Replacing the Muluki Ain, the Muluki Dewani Samhita Karyawidhi passed in 2074 states that documents recording more than 50,000 rupees will not be legally recognized if they are not certified by the local level. There was no such arrangement in the previous Muluki Ain. The judgment given by the joint bench of judges Ishwar Prasad Khatiwada and Bam Kumar Shrestha reads, “Against the officially registered land rights, it is not possible to establish the offense of adverse fraud by assuming a particular type of behavior between the complainant and the defendants.”

Billions worth of assets at risk

According to the claim of the National Christian Federation, there are 7000 churches registered in the federation, but the actual number of churches in the country is around 16000. Of these, only 35 to 40 have been registered in the District Administration Office, says CB Gahatraj, president of the federation. If the federation’s claim is to be trusted, 99 percent of the churches are running without registration.

According to the Organization Registration Act, 2034, there is a provision to register religious organizations at the District Administration Office, but the churches are not accepting to be registered according to that law. “We are saying that all religious organizations should be regulated by bringing a special law,” says Gahatraj, “If churches are run according to the Act, they will have the status of an NGO.”

Shivahari Gyawali, an activist and scholar who advocates for the rights of marginalized communities, says that religious laws are necessary to make religious institutions transparent and accountable. “Temples, mosques, churches are religious institutions that also provide social services,” he says, “All temples have not come under state regulation. Donations are offered in small temples too. Budgets are given at local levels. But as they are not regulated, the state does not get taxes.” On the other hand, he opines that a law governing religions is necessary also to keep the state neutral from religious matters, which would then regulate the places of worship of all religions.

Chari Bahadur (CB) Gahatraj, president of the Nepal Christian National Federation.

Gahatraj says that if there is no regulation of religious institutions like the church, a large amount of wealth, as well as, the faith of the followers are at risk of loss. According to him, out of the total number of churches, about 3000 churches stand on the land bought in the name of private individuals, while the rest exist in rented spaces. The property of the churches is mainly accumulated by the offering and donation of the followers. Each follower’s weekly offering to the church, monthly offering equaling a tenth portion of the income, and voluntary offerings make the churches prosperous. Additionally, some churches also bring money from abroad. Gahatraj says that even though the Federation itself brought 1 million US dollars in aid to build a cemetery from an American organization called Christian Aid in 2066, it was deposited in Sarita Thapa’s personal bank account.

Sarita is the wife of Sundar Thapa, the then-president of the Federation. But Gahatraj says that the cemetery was not built and it is not known where the money was spent. “The property bought with the donations of the believers, and local/foreign donors is not in the ownership of the church. This has created a serious discord in the Christian community of Nepal,” says Gahatraj, “Churches are becoming the arena of strife.”

Arena of strife

Claiming the property of the church, dividing the church, and building a new church is a common problem all over the country among Christians. Church leaders have been detained by the police due to such misbehavior and manipulation. Owing to a similar dispute in 2068, Pastor Elia Pradhan was arrested by the police. Former MP Binod Pahadi says that Pastor Elia was released from custody on the condition that he would return the land originally belonging to the church. Pahadi was also the coordinator of a task force formed by the then Ministry of Peace and Reconstruction in 2069 to resolve the issues faced by Christians. Elia’s son Benjamin says that according to the order of the District Administration Office, he has transferred all the properties of the church in his father’s ownership to a newly registered church.

Bethsalom Church in Putlisadak.

An example of the problems that arise when the community’s property is kept in private ownership is the Bethsalom Church in Putlisadak. The land of this church, which is considered to be the second oldest in the country and the oldest in Kathmandu Valley, has a history of partition among its registered owners. According to Jhakendra Rai, a member of the church management committee, the church was established in 1953 by Athyal, John, Kurian, and George, who came from Kerala, India. The land of this church was initially bought in the name of three people including Gupta Bahadur Shrestha.

However, after some time, Gupta Bahadur renounced Christianity and took back the land registered in his name. “I heard that Shrestha took back his share of land after a long litigation,” says Rai. The land belonging to Gupta Bahadur now houses the office of ‘Name,’ a business that conducts preparatory classes for medical education. Rai said that the remaining 3.5 ropani of land is registered in the ownership of three other people, but the church is using it anyway.

Baptist Church, Balaju, Kathmandu.

“It’s like this all over the country, property amounting to crores is in the name of individuals,” says Pasang Lama, pastor of Balaju Baptist Church, who has experienced similar claims and counter-claims. “It is said that what is given by one hand should not be known by the other hand. In practice, the property of the church is being divided for private ownership.”

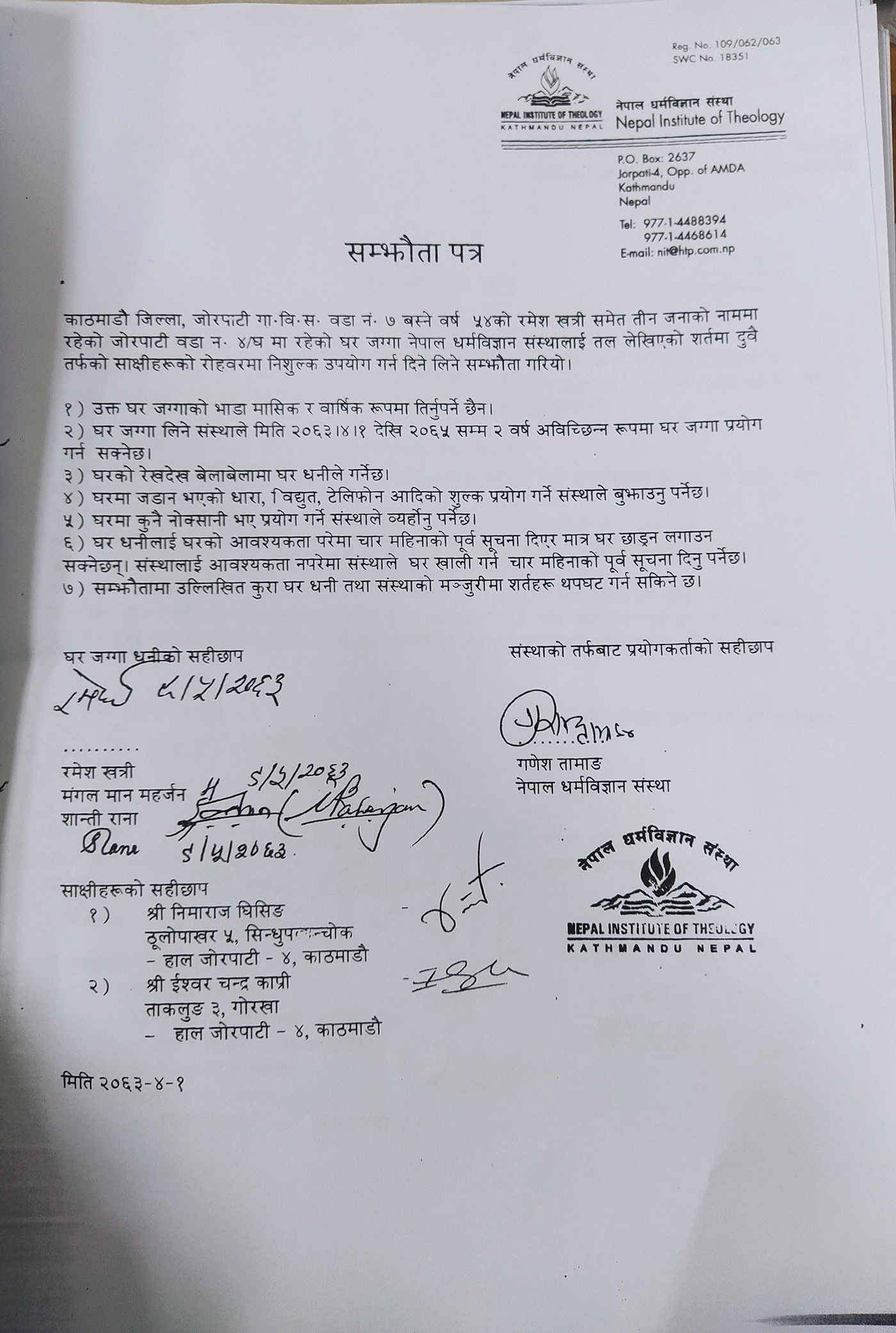

In addition to the churches, the community land remaining in private ownership has become a problem even among the institutions opened to disseminate Christian philosophy and Bible education. In the 2030s, Nepal Bible Ashram was established to conduct Bible school and Bible training. With the financial support of various foreign organizations, church leaders, and Christians, three ropani and five ana land was bought for the Ashram in Jorpati, Kathmandu. Since the Ashram was not registered officially, the land was then registered in the joint ownership of Mangalman Maharjan, Ramesh Khatri, and Shanti Rana in 2037.

Lease Agreement to Nepal Dharma Science Institute (NDSI).

When the disagreement regarding the ownership of this land was growing, the Nepal Dharma Science Institute (NDSI) under the leadership of Jeet Ghale was registered in the District Administration Office of Kathmandu on 6 Bhadau 2062. In 2068, Ghale filed a case in the district court, claiming the land right.

After that, an agreement was made between the landowners and NDSI to restore the property. There was a written agreement that NDSI would use the property free of charge for two years. The agreement made on 25 Baisakh 2064 stated that the three landowners would donate the land to NDSI. However after the rental period ended, the landowners changed their minds. Instead of donating the land, they pressured it to vacate the land. However, NDSI refused to leave the land, citing the previous agreement with the landowners. Amid the controversy, the owners transferred the land right to the National Churches Fellowship of Nepal (NCFN) on 29 Asar 2068.

In the resignation letter showing the land transfer, it is mentioned that 3 crore 26 lakh rupees was paid by NCFN. “Ramesh Khatri including three other individuals indeed took 3 crore 26 lakh rupees from you (NCFN) on today’s date,” it is stated in the registration approval document submitted to the Land Revenue Office in Chabahil. But Mangalman Maharjan, one of the land owners, insists that the transaction was confirmed in the document only to pay the revenue of the land.

NCFN is an NGO comprised of various churches. After the land transfer process, NCFN pressured NDSI to vacate the house. Executive Chairman Ghale on behalf of NDSI filed a writ in the Patan High Court with a demand for an injunction, explaining that NCFN was trying to remove NDSI from their land illegally. In Mangsir 2068, the High Court dismissed the writ.

In the case of the Kathmandu District Court, the bench of Judge Muraribabu Shrestha ruled in Chait, 2068 that “since the ownership of the land is represented by the official document of dhani purja,” the person who has the document can transfer the land right. After the verdict, NCFN became the legal owner of the land. Due to this incident, properties accumulated by devotees’ gifts and donations are at risk of being divided as ancestral property or joint investment property. “There are many such incidents, many settle disputes within the church out of fear of defamation of the religion,” says former MP Pahadi.

Either strict or ignored

Organizations Registration Act, 2034 during the Panchayat period was the legal provision that allowed religious organizations to be registered and operate. But during that period, not a single church was registered, instead, they operated secretly. During the Panchayat period, there are examples of Christians being arrested for being involved in proselytizing.

Journalist Sudhir Sharma wrote in Kathmandu Today magazine in 2055 that Christianity was introduced in Nepal after King Pratap Malla, who was gifted with a telescope in 1661 (AD), was permitted to preach the religion to two priests.

With the promulgation of the Interim Governance Act of Nepal in 2007, Christian preachers started to be active in Nepal. However, after the introduction of the Panchayat system in 2017, Christian preachers were again restricted. The Constitution of 2015 guaranteed that people could “follow and practice the eternal (Sanatan) religion while respecting the prevailing traditions.” However, it was difficult for Christians to practice their religion freely.

In 2017, Christians including Pastor Prem Pradhan, Gwara Guvaju, and others involved in proselytizing were prosecuted and sentenced to prison. Pradhan baptized some employees of Palpa Missionary Hospital on 6th Bhadau 2017 while returning from Humla. The Supreme Court then sentenced 11 individuals including Pradhan, to prison, while this verdict was published in the Nepal Law Gazette of Mangir 2018. Pradhan was jailed many times during the Panchayat for religion-related offenses.

After the restoration of democracy in 2047, on the recommendation of the interim government, King Birendra Shah pardoned at least 35 people who were serving prison sentences in religion-related cases and withdrew the cases of about 300 people who were facing trial. “On the recommendation of the Prime Minister in the context of the new political changes taking place in the country,” such instructions were given in the notice published in the Gazette on 29th Jeth 2047.

Although the multi-party system adopted a liberal policy on religion, it was difficult to register churches in practice. After 38 years of its establishment, in Asar 2055 an organization called National Churches Fellowship of Nepal (NCFN) representing various churches, was registered in the District Administration Office, Kathmandu. It is mentioned on its website that NCFN was established in 1960 (AD). This means that NCFN ran for 38 years without registration. Even now old churches such as Bethsalom Church in Putlisadak in Kathmandu and Nepal Christian Congregation in Gyaneshwar are running without registration. The plots of these churches are owned by individuals.

Churches are registered in the District Administration Office only after being forced to do so due to disputes over the property of churches and split between religious leaders. As a church legally becomes a non-governmental organization (NGO) when it operates under the Organization Registration Act, the Christian community believes that this legal system is wrong. “How can a religious organization be registered as an NGO?” Balaju Baptist Church Pastor Pasang Tamang says. He believes that NGOs need to be certain about income, and its source, with auditing responsibilities, which is impossible in churches. “The income of the church is the offering. How can we estimate the amount gathered by offerings?” he says.

Pastor Pasang Tamang, Baptist Church, Balaju.

How are religious institutions running?

In 2048, the number of Christians in the country was 3 lakh 18 thousand 389. According to the census conducted by the National Statistics Office in 2078, this number has now reached around ten lakh. Gahatraj, the president of the Christian Federation, claims that there are around 30 lakh Christians. Although the claims are varied, there is no dispute that the number of churches in Nepal is increasing with the number of Christians. However, it is strange that the state is unaware of the mismanagement of the church and the disputes within it.

Important religious sites of Hindus and Buddhists are operated through development committees and development funds. For instance, Pashupati Area Development Fund, Greater Janakpur Area Development Council, Pathibhara Area Development Committee, and Devghat Area Development Committee operate the respective Hindu places of worship. Similarly, Buddhist sites of devotion, such as Boudhanath and Lumbini are regulated through the Boudhanath Area Development Committee and Lumbini Development Fund respectively. The Buddhist Philosophy Promotion and Monastery Development Committee exists to protect and regulate viharas and monasteries across the country.

Khenpo Kamal Bhandari, president of the Nepal Buddhist Association, the umbrella organization of Buddhist monasteries, says that the number of monasteries in Nepal is around 5,000. He said that although public monasteries are registered, private monasteries are running without registration. “The number of private monasteries is very small,” he says, “but I have not come across any problems regarding private claims of ownership of monasteries.” According to Gangakumari Gurung, administrator of the Buddhist Philosophy Promotion and Monastery Management Committee, the number of public monasteries registered in the committee is 3,000. She says that the committee stopped registering private monasteries. “A monastery should not be private at all. It is automatically a community,” she says. “That’s why we stopped registering it as a private monastery for three to four years.” Gurung also says that some monasteries may have been registered in the District Administration Office, while others may have become the.

Thus, even though the places of religious and cultural faith of Hindus and Buddhists are regulated by the state to some extent, the churches of Christians and mosques of the Muslim community have to be registered as non-governmental organizations.

President of Nepal Muslim Association Nazrun Falahi says that the land of the mosque is also registered in private ownership or as non-governmental organizations. “The sanctity of religious institutions would be maintained if they are registered and regulated by formulating specific laws,” says Falahi. According to Mohammedin Ali, a member of the Muslim Commission, the old mosques in Kathmandu such as Jame Masjid and Kashmiri Takia Masjid were registered as mosques because the kings themselves had given them the land rights. “There is no problem with the ownership of the old mosques but the new ones are registered in the name of two or three individuals to avoid being registered under the Organization Act. It can become a big problem later on.”

Suresh Shrestha, Joint Secretary of the Culture Division of the Ministry of Culture, says that he did not know that the land of the churches was privately owned. He expressed surprise and said, “It shouldn’t be like that!” Narayan Prasad Bhattarai, spokesperson and joint secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs, also says that he is not aware of how the churches are operated.

Law is necessary

Clause 2 of Article 26 of the Constitution stipulates that all religious groups have the right to protect the operation of their religious sites and religious guthis. However as the churches are registered as personal property, their physical infrastructure is at risk of being destroyed. The constitution has also made provisions for the operation and protection of religious places and shrines and for the management of their property and land. In Chapter 6 of the Muluki Dewani Samhita, 2074, formulated after the promulgation of the Constitution, there is a provision that all religious activities and their finances can be managed and operated by establishing a guthi. In sub-section 2(tha) of section 315 of the said law, there is a provision that the guthis established for monasteries, temples, chaitya, mosques, churches, or other religious activities shall be public. If the property is not transferred to guthis within three months of their establishment, the guthis are dissolved. Based on these provisions of the law, church properties registered in the name of individuals can be managed and operated through guthis.

Although the property of the churches in private ownership can be protected, neither the state nor the Christian leaders have paid attention to this. Researcher Shivahari Gyawali says that the problem is caused by government indifference and church leaders who do not want to leave valuable property currently under their control. “Nowadays, there are fewer and fewer people who say that church property in the name of individuals should be registered in the name of the church itself,” he says.

It is in Dewani Samhita that guthi can be registered by submitting an application to the District Panjadhikari. The officer who registers, supervises, and cancels guthi is defined as Panjadhikari. It is also mentioned in Dewani Samhita that if the Panjadhikari is not appointed by a separate law, then the Land Revenue Officer in the district is called the Panjadhikari. This means that it is the responsibility of the Land Revenue Office to register and monitor guthi.

However, donations in churches, monasteries, and mosques come not only from followers but also from foreign countries. Foreign funds coming to the monastery can be regulated by the Buddhist Philosophy and Monastery Development Committee. But in the case of churches and mosques, there is no regulatory body at all. Advocate Swagat Nepal says that a separate law is needed for the accounting and regulation of offerings in religious institutions. Advocate Nepal says, “When some people in the community assert that privately held property should be returned to the church, the private owners would rather give up the religion than relinquish the property. Therefore, I went to 33 districts and told them the necessity to formulate the law for the property to be returned.” He says that there is a need for a specific law to regulate and manage religious organizations to prevent the wrongful use of donations and gifts from followers and foreign funders.