In the local election held a year ago, Dalit women did not give candidacy in 123 wards out of 6 thousand 700 wards. However, political parties and the Election Commission have not been able to attract Dalit women to the vacant seats.

Sabina Devkota | CIJ Nepal

In 753 local units of Nepal, 123 wards out of 6 thousand 743 wards do not have Dalit women as ward members. According to the Election Commission (EC), the seats are vacant as no Dalit women filed candidacies in the wards in the 2079 election. In the previous election of 2074, out of all ward member seats reserved for Dalit women, 170 were vacant.

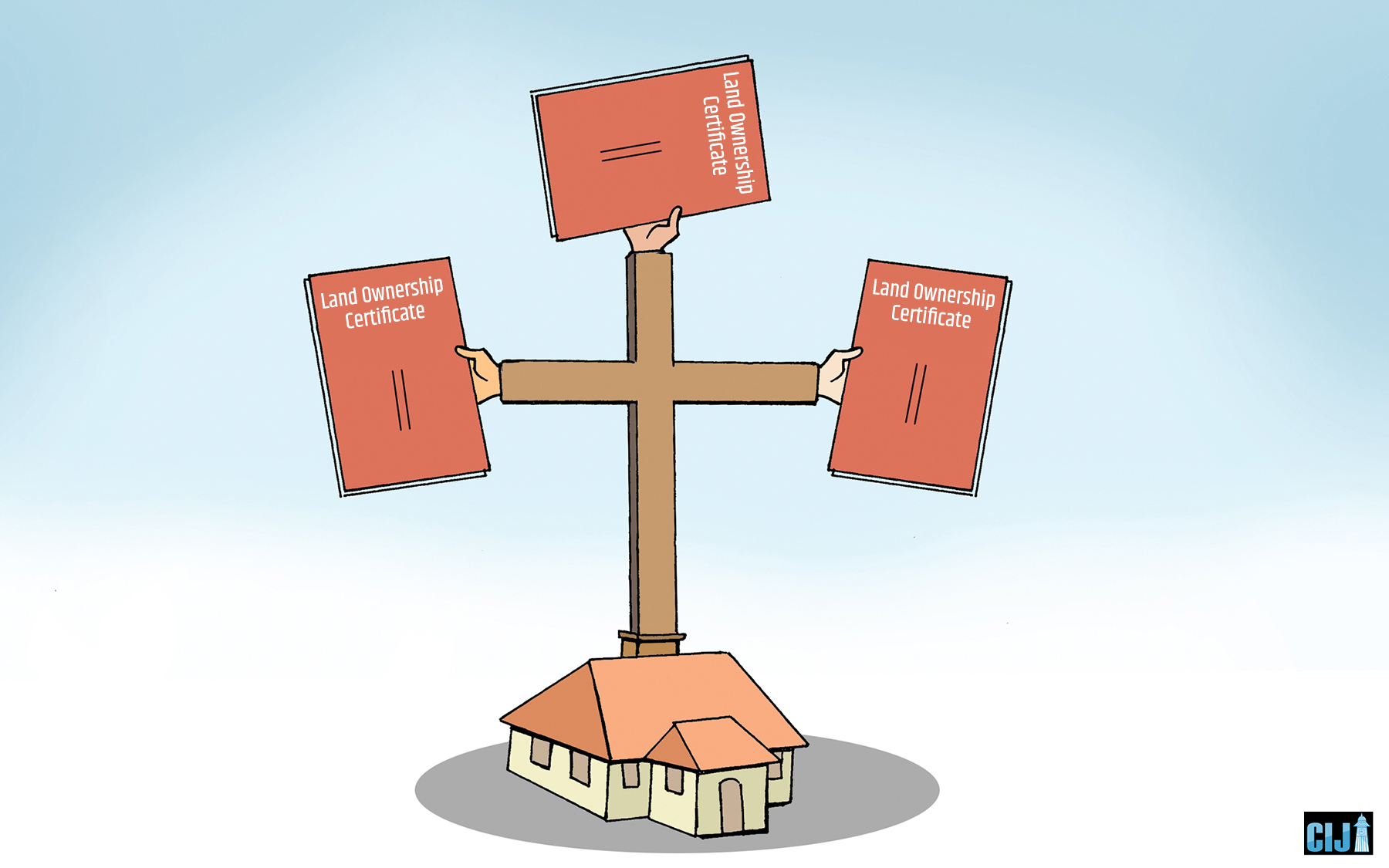

Although the constitution has made it compulsory, why did these wards not have candidacies from Dalit women? Is it because there is no Dalit community in the said wards or is there a wider socio-economic reason behind it? Without delving deeper into these questions, EC has prepared to amend the laws and allow other women to fill up these seats. It has already drafted a bill for this purpose.

On Asar 18, 2080, EC presented the amended and harmonized draft bill to the government so that it could be taken to the parliament. Article 74 (4) of the draft bill states, “Any ward that does not have candidacy from Dalit women in the reserved seats, can have women of the minority community as candidates.”

However, the claim of EC that it was forced to propose the draft bill as the Dalit community does not live in the wards with vacant seats does not match with facts. According to a study conducted by the Centre for Investigative Journalism (CIJ), out of the 123 wards without candidacy, 65 wards do have Dalit women as residents. While studying the voter list of the wards, 50 of them do have Dalit women as voters. According to the IEEAMIS system of the Education and Human Resources Development Centre, out of the 123 wards, Dalit students residing in the 40 wards have been given scholarships. 25 wards have both – Dalit students with scholarships and Dalit women as voters.

Ignorance of EC and Negligence of Political Parties

Padam Sundas, Dalit activist and former ambassador. Photos Savina Devkota

Without analyzing the reasons for the vacant seats of Dalit women ward members, EC already sent a draft bill to amend the laws and allow other women to fill up these seats. Activists have called this a conspiracy to cut down the reserved seats of Dalit women.

Dalit activist and Former Ambassador Padam Sundas said, “This process aims to directly snatch away the reservation. If this draft bill becomes the law, then it will ensure that other women will be made candidates where Dalit women have not given candidacy.” Another Dalit activist and researcher JB Biswokarma said that before proposing the draft bill, the EC must have ensured whether the wards have Dalit residents or not. He said, “Ignoring the fact that 98 percent of wards do have Dalit women as ward members, the constitutional reservation must not be taken away in the pretext of 2 percent of wards.”

According to Dalit activist and researcher Bhola Paswan, since the law mentions “Dalit or minority” instead of “Dalit” for certain executive roles in municipal assemblies and rural municipal assemblies, the Dalit community has lost at least 54 percent of executive roles. He said, “If this new draft bill is passed, then the representation of Dalit women will further decline. This is a game to deprive the Dalit community of representation.”

However, the EC Chief Commissioner Dinesh Thapaliya is not ready to accept the allegation. He said, “We are not taking away Dalits’ rights, we are seeking for representation of women.” He remarked that when other women can be represented in the 123 wards as alternative candidates, their right is now violated. Thapaliya further said that it is the responsibility of the Dalit community and the political parties to encourage Dalit women to candidacy in the seats reserved for them. He said, “We can add ballot boxes, and specify dates (of elections) but cannot find candidates for the election. It is not the responsibility of EC to check the demography of wards.”

Devraj Biswokarma, ational Dalit Commission Chairperson

The Election Commissioner Janaki Kumari Tuladhar said, “It is the constitutional spirit that each ward needs to have at least two women members. But if Dalit women do not give candidacy, other women should come to fill up the seats. Otherwise, our Sustainable Development Goal of ensuring 42 percent representation of women in local elections until 2030 will not be fulfilled.”

National Dalit Commission Chairperson Devraj Biswokarma claimed that if there is a proper investigation on the Dalit community with non-Dalit caste, then 99 percent of the wards with vacant positions will have Dalit residents. He said, “This is our job too but with a limited budget, we could not do the research before the election. There are other mechanisms to ensure the minority community’s representation. However, it is not a good practice to bring others in positions specifically allocated for Dalits.”

Paswan commented that Dalit women not giving candidacy is the fault of political parties. He said, “Political parties know that there are Dalit communities in their wards and they need to be encouraged for candidacy.” So, what must be the reason that the representation of Dalit women is not prioritized by political parties? “This is completely a politics for votes,” said Paswan. “This is related to how many votes and money you get by making somebody a candidate.”

Constituent Assembly Member and Nepali Congress leader Jivan Pariyar accepted that Dalit women not filing candidacy in their wards is the responsibility of major political parties. He said, “When the Election Commission said that they did not receive candidacy, we understood that the wards did not have Dalit residents. But I am shocked after reading this research.”

Former Prime Minister and Chairperson of Nepal Samajbadi Party Baburam Bhattarai said that CA members had not thought of the situation of wards not having Dalit women. He said, “We wanted to desperately engage with women and Dalit but we never considered that there are wards without Dalit community.”

One Intention, Many Reasons

Suresh Dhakal, a professor of anthropology at Tribhuvan University, said that it should not be assumed that Dalit women who are landless, below the poverty line and at the bottom of the power structure, will willingly come forward as a political candidate. He further said that instead of encouraging Dalit women to participate in politics, it will be dangerous to look for alternatives after seeing some empty seats.

Dr. Triratna Manandhar, Retired Professor, Department of History

Dalit women have not filed candidacy in some wards because of the ignorance of political parties, while in some other wards, the seats have been filled by self/encouraged migration.

Dhakal said that it is just not the whole truth that the seats have gone vacant due to Dalit community not residing in the wards. The exercise and expansion of caste system mandated that Khas-Arya and Dalit communities migrated in all wards of Nepal barring a few exceptions. Dhakal suggested that further investigation could be done with the coordination of the statistics division and the EC.

Dalit women not giving candidacy for the ward member position is also due to the wider discrimination against the Dalit community and patriarchy that prevents Dalit women from securing positions. Kamala Gyawali Shripali, a Dalit woman ward member of Bhajani-6 in Kailali has similar experiences.

“This time I had registered my claim for the deputy mayoral position but the coalition made another person the candidate. I discovered that the Dalit woman member does not have any substantial role, so I did not want to go for it again,” said Shripali. As she is also a student of law, she is aiming to file candidacy for an executive position in the next election. Regarding her ward not have Dalit woman candidate, she said, “This ward has some Dalit families but they did not file candidacy as they said they do not understand politics.”

Migration for reservation

Although some wards do not have Dalit woman candidates due to ignorance of political parties, in some other wards, the positions have been filled up by deliberate or encouraged migration. Santamaya Sunar migrated to Helambu-5 in the last election after she found out that the ward did not have a Dalit woman ward member in the 2074 election. She filed candidacy as a Nepali Congress candidate and has been elected without any competitors. She said, “Before I was a member of Ward 4. When I found out that Ward 5 did not have any Dalit woman members, then I bought a small piece of land and migrated here, updated this in the voter list, and became elected without any competition.”

Padamkanya Kami elected from Kanakasundari Rural Municipality-7 in Jumla unanimously, also migrated to the ward. Nevertheless, her current residence is in Ward 8. She said, “After learning that ward 7 does not have candidates, I bought land here. Having been elected unanimously, I am also a member of the executive committee.” 35 years old Goilu Kami, now a member of Jumla’s Guthichaur Rural Municipality-2 also migrated from Ward 3. Her party, Unified Socialist managed a land for her so that she could migrate to the ward.

This kind of migration is taking place not just with the initiative of political parties but also on an individual basis. Currently, a ward member, Lalsari Sunar said that Narabahadur Thapa, a businessman of Patarasi Rural Municipality-7 in Jumla gave her land freely so that she could migrate from Ward 3.

Researcher JB Biswokarma said, “If individuals migrate to take the opportunity from the reservation, that is a welcome step, just like how Chitwan’s Prachanda went to Gorkha. This can be a method to decrease the vacant positions of Dalit women ward members.”

However, anthropologist Dhakal questioned whether the migration just to get elected at the local level can be impactful. He said that although it is not unnatural to migrate for better opportunities, this may have long-term negative impact on the previous ward’s community, culture, environment, and society.

Migration: Opportunity or Humiliation

In the definition of the National Dalit Commission, Dalits are those communities who are marginalized economically, socially, politically, educationally, and culturally on the basis of religious superstition of impurity and untouchability. Although they are sidelined from the state’s mainstream, they have contributed immensely to the state-building process through their labour, skills, and art.

However, the Commission does not have a single ethnicity from the Himalayan region listed under the Dalit community. Anthropologist Tasi Tewa Dolpo said that Dalits from the region still have not been given due recognition because of the state’s centralized mindset.

Dolpo said, “Dalit activists and organizations do not go to the Himalayan region, nor there has been any research about it. The region has practices of untouchability, purification processes, punishments, not allowing Dalits to enter home easily, stigma against marriage with Dalit, and discrimination even in last rites.” He opined that Dalit communities can be found from Taplejung in the east to Bajura in the west, however, their identities may differ by geography.

He said, “Dalits in the Himalayan region include Khotrog in Nesang community of Manang, Mustang’s Mendig, Kunsang’s Ghyupa, Chhura and Dhokpa, Dolpo community’s Gara-Bera, Mandre Khampa in Humli community, Lha Khampa and Luhung Khampa of Khampa community in Bajura.”

However, the Dalit community faces extreme injustice even in the Himalayan region. A Dalit woman with Lowa caste had filed candidacy as a Dalit woman ward member in the local level election of 2074 at Lomanthang Rural Municipality-5 of Mustang. But her own brother forced her to withdraw from the election as he believed she “tarnished family’s honor” by being a candidate in a reserved seat.

According to Former Ward Chair Himjing Dorje, since then nobody has dared to file candidacy in the Dalit quota. He said, “We do have a Dalit community here but since they feel humiliation when identified as Dalit, Biswokarmas here change their caste as Lowa.”

Dolpo said that the Nepali state needs to bring in the marginalized Dalit communities of the Himalayan region to the social and political mainstream. He remarked that when there is a debate going on regarding cuts in reservations in other parts of the county, the Dalit community in the Himalayan region is not even aware of the oppression they face. Dolpo questioned if there is anybody at all who would speak up for their identity and representation.

There are diverse views regarding the reservation within the Dalit community. Some have taken it as an opportunity, while others see it as an embarrassment. This can be observed not just in rural areas but also in Kathmandu, Bhaktapur and Lalitpur.

In the past local election, 32-year-old Devi Pujari (name changed) filed candidacy as a Dalit woman ward member in a certain ward of Kathmandu Metropolitan City, representing CPN (UML). Like other candidates, she also went to the streets to campaign for votes. However, an old person said to her, “Don’t you feel ashamed to stand in the election as a Dalit? Now, everyone knows you are a Dalit, they will humiliate you. Who will marry you now?”

Some locals from the Pode community even tried to smear Devi’s face with black paint. This is not a new experience for Devi. When she stood in the 2074 election for the same position, she withdrew from the election at the last minute, owing to the pressure exerted by the local Pode community members. She said, “We have not yet been successful in making them understand that reservation exists to correct historical injustices against us.”

In the local level election of 2074, Riju Kapali of Nepal Majdur Kisan Party filed candidacy for the Dalit woman ward member in Bhaktapur-7. The Election Commission accepted her candidacy and she was elected without competition. However, after she was elected, the Kapali community and her family (excluding her husband) boycotted her and forced her to resign. Since then, she is living away from her in-laws. This time around, the Dalit woman ward member position is vacant.

The Kapali community claims that although they are socio-economically towards the bottom of the Newar community, they are not Dalit. Since the 2058 protests, the Kapali caste is not listed as a Dalit caste. Likewise, the Deula community has also recently demanded to be delisted from the Dalit caste groups.

There are two strands within the Deula community. The first group is ready to accept itself as a Dalit caste, however the second group has applied to the Dalit Commission to be delisted from the Dalit caste groups. The Dalit Commission indicated that the case is under consideration.

Retired Professor Dr Triratna Manandhar from the History Department of Tribhuvan University said, “The Newar community has a very harsh caste system. The Dalit community with Newars tend to see reservation as humiliation rather than one’s identity, representation and existence.”

Dalit rights activist and researcher Shiva Hari Gyawali said that many Dalits who have changed their caste fear humiliation if they are identified as Dalit. According to Gyawali, this is a reason that adds to the risk of Dalits being under-represented in the next local-level elections.

What is the alternative?

Dalit rights activists remarked that the Election Commission must first declare that a ward does not have Dalit residents, then only it can find alternatives for the vacant position of Dalit woman ward member. Gyawali said that both the EC and the Dalit Commission need to be made accountable for whether the wards do not have Dalit residents or whether the Dalit residents have not been identified in the first place.

Paswan suggested that the EC must first ensure whether there are Dalit residents in the said ward, and make it compulsory to register all candidates along with Dalit woman member candidates. He said that this needs to be done before sending the election officer during elections. This practice can serve to encourage Dalit women’s candidacy. He said, “The alternative to Dalit reservation is only Dalit reservation, nothing else.”

According to JB Biswokarma’s research, it is only because of the reserved seats for Dalit women ward members that the Dalit community saw a representation of 21.99 percent in the 2079 local election, which is 8 percent more than the Dalit population proportion.

However, when compared to the 2074 local election, the election in 2079 saw a decline in number of Dalit representation in executive roles. In 2074, there were 6 mayors and 11 deputy mayors from the Dalit community, while this time around, there are only 3 mayors and 11 deputy mayors.

Ward chairs increased to 5 from 1, however, vice chairs decreased to 6 from 17. The study stated that the election did not become inclusive because the structures of central committees of political parties are exclusive and undemocratic.

Political Scientist Krishna Hachhethu remarked that as the position of Dalit woman ward member is not an executive role, Dalit women are not attracted to it. He said, “Reservation is used worldwide as a method to redress the historical oppression faced by communities marginalized and made powerless socially and economically. But the reservation must be enhancing ability, power, and role of the communities, it should not be just cosmetic.”

JB Biswokarma commented that philosophically, reservation is not an agenda of liberation but that of reform. He further said that reservation is not the goal scorer of the game but it allows Dalits to understand the rules of the game and who makes the rules. He said, “When you are outside the ground, you cannot see many things. At least, Dalit women are aware of the game. They now have aspirations to become the ward chair at least once. Yesterday, people felt the water Dalits touched was impure. But today they need a Dalit representative’s signature on official documents. Seeds of Dalit women’s confidence have thus been sown.”

This is the reason why Dalit women rights activists think that the quota for Dalit women ward members must not be abandoned at any point. Durga Sob, the founder of Dalit Mahila Sangh, said, “It is an attempt to deprive Dalit women of their legal opportunity by painting Dalit women not filing candidacy as non-existence of Dalits. The draft bill proposed by the Election Commission should not be passed by the parliament at any cost.”