Nepal’s mountain region is witnessing excessive rain in recent years because of rising temperatures. But these areas lack temperatures and rainfall measurement systems. Climate change-induced disaster risk could be minimized if local governments are technically equipped for weather updates.

Mukesh Pokhrel | CIJ, Nepal

When a heavy flash flood occurred in Melamchi in mid-June this year, the weather around Melamchi Bazaar was all clear. Surprised by sudden floods despite no indication of rain around the area Hasta Pandit and other locals predicted the flood in the area occurred due to glacial lake outburst.

The flood caused widespread devastation, damaging personal properties and claiming lives. Next day, a team of locals led by Nima Gyalze Sherpa, Helambu Rural Municipality chief, headed towards the highland with a helicopter. They witnessed massive landslides in Bhemrathang and captured pictures of sediment carried by the flood. By analyzing pictures geologists and meteorologists concluded that landslides and floods occurred because of incessant rain. But none of them were successful in measuring rainfall precipitation as there’s no weather station around the landslide-hit area.

After studying landslides that occurred in Melamchi, Pemdang, Yangri and Larke, Shiva Baskota, a senior geologist at the Department of Mines and Geology, concluded excessive rain might have occurred. “It seems massive rainfall occurred in Melamchi, Larke and Yangri rivers,” said Baskota adding, “But there’s no weather station so it’s difficult to predict rainfall precipitation precisely.”

Baskota, who spent four days together with his team to study the devastation, says around 1.5 million cubic meter of debris deposited in Bhremthang due to landslides in the water source of Melamchi and Pemdang River.

Bhemathang is the confluence of Melamchi and Pemdang rivers. Landslides have occurred here due to high rainfall. Photo: Shivakumar Baskota

Sindhupalchowk-like excessive rainfall was recorded in Manang too. The rainfall continued for four consecutive days. Temba Dorje, 80, says he had ever experienced rainfall like this year in the mountainous range.

The rainfall was so massive that the overflooded Marsyangdi River fully destroyed 45 houses. Several infrastructures in Talgaun, Dharpani, Chame and Manang were damaged. Local governments in Manang have reported that excessive rain caused loss of properties worth Rs 4 billion. Against minimal rainfall trends Manang reported an increase this year. Nevertheless, the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM), which keeps the nationwide weather records, has no exact measurement of Manang for this year.

Weather stations have been installed in Humde (3353 meters) and Chame (2650 meters) of Disayang Rural Municipality, Manag, which doesn’t cover high altitude areas. But flash floods were witnessed in villages above 4000 meters. Massive rain was reported in Khangsar, Shreekharka, Tilicho Base Camp and Yak Kharka. Due to the lack of measurement system in the area it’s hard to measure the rain precisely.

Nepal’s mountain region lacks enough weather stations to measure rainfalls and temperatures. A few manual meteorological observation stations established are defunct.

Of the total five manual meteorological observation stations installed above 4000 meters–Khamachin of Taplejung (4242 meters), Nup of Rasuwa (4091 meters), Paigotang of Rasuwa (4091) Nar of Manang (4195 meters), Fu of Manang (4100 meters), only Nar weather station is in operation, according to DHM.

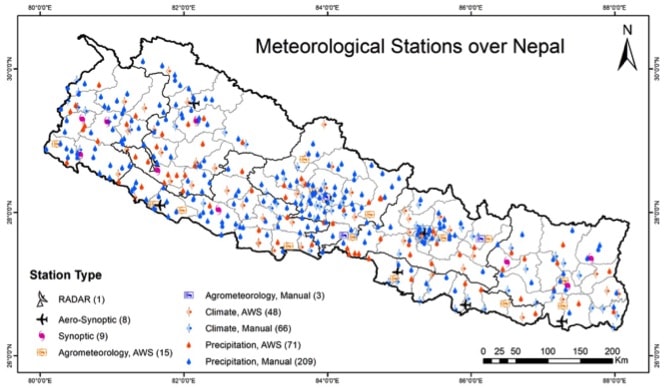

The World Meteorological Organization states synoptic observations should typically be representative of an area up to 100 km around the station to get precise rainfall and temperature forecasts. Former secretary Rishi Ram Sharma, who worked as director general at the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology, says if the weather forecast criterias of the global meteorological body is to follow the universal standards, Nepal needs to install around 14,718 weather stations, which is a difficult task considering complex geographical terrain and weather. Currently, Nepal has only 600 stations for measuring temperatures and rainfalls, according to the department.

A DHM official says the Finance Ministry never prioritizes installation of weather stations. The official complains of not getting enough resources to install these stations and keep them functional. “Why do you need weather stations? Everything is available on mobile,” he quoted the finance ministry officials as saying and added, “Policy makers don’t know that weather stations are essential even to get information on mobile.”

Information collected from old and manually operated weather stations lack credibility. Yet, the department doesn’t receive collected data on time. Ram Prasad Awasthi, a spokesperson for DHM, says generally field officials collect temperature data twice a day –8:45 am and 5:45 pm–whereas rainfall data is collected every 24 hours. Employees deployed to collect data from weather stations merely receive Rs 30 daily wage for their work. Since their daily pay is too little, an official said, there’s the tendency of self-predicting the temperature and sending it to the department on a weekly basis.

Rajendra Sharma, a senior hydrologist at the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority (NDRRMA) says installation of automated weather stations is essential in high altitude areas for receiving accurate weather updates. Coordination with telecommunication service is essential as automated weather stations require better connectivity for full fledged operation. Given that situation, automated weather stations can send timely information via mobile network.

DHM estiamtes it costs around Rs 3,000,000 to install a fully automated meteorological weather station. If the station is to be operated by humans it would cost around Rs 3,00,000 to collect temperature, rainfall, humidity and air pressure related information.

Why do we need weather stations?

Due to rising temperatures and global warming, the weather system is changing. Consequently, the mountain region known as rain-shadow area is experiencing erratic rainfalls in recent days. A report published by German Watch has ranked Nepal as ninth vulnerable country in terms of climate change hazards. Weather stations are essential to understand impacts of climate change in mountains and disaster risk mitigation.

Now defunt Automated Meteorological Center at Rara, Mugu. Photo: Department of Water and Meteorology.

DHM’s senior meteorologist Indira Kandel says the department is unable to install weather stations in high altitude areas because of geographical remoteness and no human settlements available in those areas.

Weather information is crucial to study possible climate change induced disasters and changing climate. In Nepal, getting real time weather data isn’t possible due to lack of adequate weather stations. Yet, geographical remoteness and diversity in weather conditions complicate in obtaining accurate weather forecasts.

Weather information is equally important for farmers while harvesting crops. That helps them to ensure social and food security. The DHM can forecast the probability of droughts, floods and landslides only when it gets weather information. Nepal needs hi-tech weather stations to measure general things such as temperatures, air pressure and humidity.

Local governments can do it

Kathmandu-based DHM headquarters and its regional offices are responsible for operation and monitoring of all weather stations. Because of resource crunch the department hasn’t been able to monitor and take care of those weather stations. Given this context, climate change experts say, the department’s financial and workforce burden could be eased and weather information could be more reliable if local governments get this responsibility.

“It’s the department’s job to measure rainfalls so such responsibilities should be given to local governments,” said Dahal adding, “Since the community itself is involved at the local level they will repair the station and will know how important weather stations are.”

Dahal says if the weather stations are operated by the local government they can use local radios to disseminate weather related information more effectively.

Former Secretary Sharma, however, suggests local authorities empower the local government only for monitoring and safety of weather stations, but not to give them full operation authority arguing management of technical manpower can be an issue.

“If the information acquired from the automated stations are installed at the local level they will inform if any technical glitches emerge there,” said Sharma, “Local governments can be empowered only for repairing the stations and taking their care.”

As of now, three is no coordination among three tiers of government federal, provincial and local governments. Nor have they started discussion in empowering local bodies in line to operate weather stations at local level.

Fast changing Himayan landscape

Plants and wildlife had started to move to higher elevations some 20 years ago because of higher temperatures caused by climate change. In recent days, loss of life and physical properties is on the rise as climate change is remaking the fragile Himalayan region witness unprecedented rainfalls.

Reservoir area in Pemdang. Photo: Shivakumar Baskota

Not long ago, rainfall which was limited between Chure to mid-hill range used to cause massive floods and landslides. The same devastation has now moved towards the fragile mountains. Climate change expert Ngamindra Dahal says climate change induced disasters in the Himalayas were never destructive like this year. “Massive rainfalls in Mustang, Manang and Sindhupalchok indicate rainfall is also moving to higher elevations,” says Dahal adding, “Rising temperatures pushed monsoon clouds towards higher elevations. That’s why heavy rainfall is reported in high altitudes.”

According to research published in Nature, the water holding capacity of the universe increases by seven percent if temperatures rise by one degree celsius. Temperature has risen by 1.2 degree celsius since 1850. In 2016, UNFCCC member states had signed an agreement to limit the 1.5 degree celsius temperature rise by the end of this century.

A report published ahead of COP-26 has warned the target of limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degree celsius would be an unachievable goal. Another climate change report published by IPCC states global net human-caused emission of CO2 would need to fall by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030 and reduce it by 25 percent if temperature rise is to limit to 2 degree celsius.

DHM data shows Nepal’s average temperature rise stands 0.056 degree celsius. Temperature rise trend is high in hill and mountainous regions. The department’s record shows annual average temperature rise in Nepal’s high hill areas is 0.068 degree celsius, 0.052 degree celcius in mid-hill, 0.030 in Shivalik range and 0.021 in Tarai region. Both minimum and maximum temperature rise in Manang is high. Manang’s annual temperature rise trend is 0.092, according to the department. Climate change experts blame rising temperature as the key reason behind massive rainfall in the Himalaya region.

Dr. Subodh Dhakal, an associate professor at the Department of Geology under Tribhuvan University, says geology and soil of high altitude areas like Manang and Mustang always remain fragile. Even a minor rainfall can cause massive destruction. “That’s exactly what happened in Manang, Mustang and Sindhupachok,”says Dr. Dhakal.

A report published by the Ministry of Forest and Environment shows cases of climate change induced disasters are increasing in recent days. The report, prepared by analyzing the prevalence of such incidents between 1971 to 2019 shows avalanches, thunder storms, snowstorms, heavy rainstorms, tornadoes, cold wave, hot wave, floods, pandemic and landslides are becoming too common.

Each year, on an average 420 people lost their life in Nepal due to climate change induced disasters, states the ministry’s report.

Weather stations help

This year, western part of Germany, China and India witnessed cloudbursts. This caused huge devastation as rainfall supposed to occur for a long time period poured in a few hours. On July 20, 644 mililiter rainfall was recorded in Zhengzhao of Henan province, China, in 24 hours.

Dr. Dhakal, says geology and soil of altitude areas like Manang and Mustang always remained fragile; even a minor rainfall can cause massive destruction. “That’s exactly what happened in Manang, Mustang and Sindhupachok”.

A report published by the Ministry of Forest and Environment shows cases of climate change induced disasters are increasing in recent days. The report prepared by analyzing the prevalence of such incidents between 1971 to 2019 shows avalanches, lightning, snowstorms, heavy rainstorms, tornadoes, cold wave, hot wave, floods, pandemic and landslides are rising.

Each year, on an average 420 people lost their life in Nepal due to climate change-induced disasters, states the ministry’s report.

Weather stations help

This year, Western Germany, China and India witnessed cloudburst. This caused huge devastation as rainfall supposed to occur for a long time period poured within a few hours. On July 20, 644 mililiter rainfall was recorded in Zhengzhao of Henan province, China, in 24 hours.

Citing Chinese meteorologists, a report published in Yale Climate Connection states average annual precipitation in Zhengzhou was recorded 640.9. But the rainfall expected to fall in a year occurred in 24 hours. Senior Chinese meteorologist Minghao Zhou informed that 201.9 millimeter participation recorded in an hour was a record high.

As reported by CNN citing data from the European Meteorological Society, 207 millimeter precipitation was recorded in nine hours on July 15. Likewise, cloudburst was reported in rural Kistabadh of India’s Jammu and Kashmir. Eight persons were killed and 17 are missing, as per India media reports.

Experts say the changing climate is the reason behind massive downpour. According to a report published by the Yale Climate Connection high temperatures cause more liquid water to evaporate from soil, plants, oceans, waterways, becoming water vapor. This additional water vapor means there’s more moisture available to condense into raindrops when conditions are right for precipitation to form.

A report published by CNN by quoting Hannah Cloke, a professor of Hydrology at the Reading University also states temperatures rise is the reason behind excessive rainfalls.

Weather stations installed in the aforementioned areas helped to measure rainfall and analyze changing climate. Downstream residents in these vulnerable areas were successful in moving to safer places. In Nepal and India, people have no idea about rainfall precipitation in the absence of weather stations despite increasing casualties and property losses. For example, more than 800 people were killed in 2013’s floods and landslides triggered by excessive rainfalls in India’s Hrikesh, Badri and Kedarnath. The water-induced disasters damaged 1,307 kilometers of road and swept away 147 bridges.

A report published in The Hindu states cloudburst had caused the deadly devastation in India. Meteorologists say more than 100 millimeter rainfall precipitation in a defined area in an hour is cloudburst. But the rainfall wasn’t measured.

Cloudburst was also the key reason behind last year’s floods in Nepal’s Baglung, Parbat and Achham districts. As the temperatures rise, air pressure reaches higher altitudes and it causes excessive rainfall when its moisture pressure reaches a climax. “Possibility of cloudburst remains always high in Chure, Mahabharat and hilly region,” said Dahal, “Cloudburst used to occur in the past too but not in Himalayas. Now, it’s happening in the Himalayas too. It seems it will keep happening.”

When floods hit Bhuji of Baglung and Kailash Khola of Achham last year it was assumed a glacial lake outburst in highland areas. But later it was known that devastation happened there because of cloudburst above the settlements.

Risk of Avalanche

Apart from frequent downpours, the risk of avalanche and glacial lake outburst is looming large in the Himalaya region. Flash floods in India’s Uttarakhand are recent cases of glacial outburst. On February 7 this year, 171 people died, 26 people are still missing whereas physical infrastructures worth 2.66 trillion rupees were damaged after glacial outburst caused massive floods in the mountain region.

Gangapur lake at an altitude of 3540 meters in Manang district, which is flooded by continuous rains and floods. Photo: Mukesh Pokhrel

Similar incident had happened in Nepal’s Seti River some nine years ago where 31 people died and 40 disappeared after landslides hindered the flow of the river. Santosh Nepal, a water resource and climate expert at the ICIMOD, said climate change induced multiple hazards are happening in Hindu Kush Himalayas.

“Avalanche induced floods have been causing a loss to hydropower projects. If massive floods damage dams some day downstream populations will face an even bigger crisis,” says Nepal. He says run off the river hydropower projects, downstream settlements and development infrastructures are at greater risk in the context of the number of glacial lakes and their size increasing in the Himalayas.

A new glacial inventory report prepared by UNDP and ICIMOD in 2020 has identified 47 potentially dangerous glacial lakes within Koshi, Gandaki and Karnali river basins of Nepal, the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, and India. Of them, 31 glacial lakes are categorized as highly critical. Among highly dangerous 31 glacial lakes 21 are in Nepal and India.

Since snow is melting in the Himalayas due to rising temperature, the risk of glacial outburst is high in the mountains.

Due to climate change, the total number of glacial lakes in three river basins increased to 3624 in 2015 from 3601 in 2000 whereas the area of these lakes increased 195.39 square kilometer from 179.56 km square in 2000. Between 2000-2015, an additional area of 15.8 km square increased with formation of 23 new glacial lakes.

Downstream settlements will face massive impacts in case these glacial lakes outburst. More than 66,000 square kilometer fertile land was damaged because of floods in Bhotekoshi after Tara Tso Rolpa glacial lake of Tibet burst in 1985. Hundreds of houses including 12 bridges, 27 kilometers of road section and Sunkoshi hydroelectricity project were swept away by large floods and significant damage ensured in 1981’s Zhangzangbo glacial lake.

Earlier to this, the floods triggered by glacial lake burst had damaged Sunkoshi and Dudhkoshi micro hydroelectricity projects. In 1985, Dig Tsho GLOF destroyed the nearly completed Namche Small Hydroelectric Project, in addition to causing other damage farther downstream. This incurred $1.5 million for the hydropower project. Likewise, the Sunkoshi Hydro Electricity project was damaged due to floods in 1981.

Rising temperatures have increased risks of glacial lakes, excessive rainfalls and landslides. Experts stress on the need of prioritizing sustainable development considering extreme climate events as a ‘new normal’ phenomenon. To move ahead for sustainable development, we need adequate hi-tech weather stations.

What Next?

No substantive progress has been done in identifying landslide prone and vulnerable areas although it looks doable. Basanta Adhikari, assistant professor at the Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University, says the government’s disaster response priorities are nothing other than post-disaster rescue and relief distribution.

The territory between Tilicho base camp and Shrikharka at an altitude of 4,000 meters. Here, too, the rains have begun to flow. Photo: Mukesh Pokhrel

“Risk could be minimized if settlements from landslide and flood-prone areas are relocated and downstream people are timely alerted,” said Adhikari adding, “Hastily built infrastructures and settlements multiply loss. Nobody is concerned that the settlements being built along river sides will face disaster someday.”

The government’s Land Use Policy-2068 has a provision of promoting urbanizations in a planned way by maintaining a delicate balance between development and environment and categorizing land, protecting and managing it. But the policy has been rarely implemented in practice. Instead, the number of people living along the river side is increasing every year. River banks in mid and high Himalayan areas are filled with unmanaged settlements. These settlements are extremely vulnerable to floods and other disasters.

Once fertile and flat lands are now filled up with concrete structures. This google earth picture shows it clearly. As seen in the picture, only a few houses were in Melamchi 20 years ago. Recently, houses are built up to the river banks. Sandhikharka of Arghakhanchi, Tinau of Butwal, Bhalubang of Dang and Manahari of Makanwanpur are few places which can be taken as textbook examples of unplanned urbanization. (See photo).

NDRRMA’s chief executive officer Anil Pokhrel says haphazardly developed settlements and other infrastructures could cause massive destruction in the days to come. Pokharel, who visited last year’s deadly floods in Baglung and Achham, says devastation in mid-hill areas was the result of unmanaged settlements. Downstream settlements of Bhuji Khola, Baglung, were swept away because of floods in the high Himalayan region where 10 people were dead and 34 disappeared in floods. In Achham, 12 people were dead whereas five people are still missing because of flash floods that occurred on August 19 last year.

Excessive rainfalls, floods, landslides and glacial outbursts have added additional challenges for underdeveloped countries like Nepal. But the government hasn’t taken any serious steps to mitigate such risks and keep its citizens safe from climate change induced disasters.

Arguing that the climate change induced disasters will increase in the future experts working on this issue stress on the need of adopting risk reduction ways. Raju Pandit Chhetri, who has been advocating about the climate crisis in developing countries in national and international forums, says it’s already late in calculating and mapping possible hazards and acting to mitigate them accordingly.

“From now onwards, climate change should be linked with the development activities, not just as an environmental issue,” Chhetri says, “While building bridge, road and other development infrastructures we should now think whether the climate change induced disaster would affect them.”

Chhetri says our physical infrastructures should be climate resilient and they shouldn’t be built around disaster prone areas.

Madhukar Upadhya, a watershed expert who writes on emerging challenges of managing the climate crisis, says a robust information system should be developed to receive minor weather related information on time.

“So far, we have received macro level information so micro information collected from the ground helps us to reduce disaster risk,” says Upadhya stating that rather than just saying which province will witness rainfall or normal weather conditions the information should be about weather conditions of specific river basins or mountains.

***