Due to lack of ambulance service in Barahakshetra, a municipality of 80,000 population in the district of Sunsari, pregnant women and other serious patients die on their way to hospital.

Santosh Gupta | CIJ, Nepal

In May last year, Narayan Jha, desperately tried to arrange an ambulance to take his mother suffering from fever to hospital. His efforts went futile.

Four days later, his mother Sudhira Jha aged 53 collapsed at home.

“I had taken her to Chatara Health Post for treatment after she wasn’t feeling well,” said Narayan adding, “Doctors had prescribed us to take her to Ghopa camp, a hospital based in Dharan. I requested all privately run ambulances but they all refused my pleas to make an ambulance ride citing Covid-19.”

As briefed by Narayan it wasn’t possible to carry his ailing mother to hospital on his back. Four days later she got sick, he somehow managed a four-wheeler from the municipality. But she was pronounced dead shortly no sooner after doctors saw her at a hospital in Dharan.

Like Sudhira, locals of Barahachhetra, which is considered an accessible area in many ways as compared to other areas because of its easy access to road connectivity, are dying because of not getting access to ambulances.

The nearest ‘Singha Durbar’; yet a distant dream

Failed to arrange ambulances six locals have died in this municipality in a year, according to locals. Four deceased including three covid-19 infected women were from ward no. 2 and war no. 10 of the municipality. Another pregnant woman from ward no. 4 faced a similar fate in May. On December 10 last year, a cancer patient from ward no. 1 breathed her last because of not getting access to an ambulance service.

Barahakshetra Municipal Office.

Despite different ailments, the key cause of death behind the aforementioned deaths was the same: unavailability of timely ambulance service. For locals ranging from relatively accessible Chauribari to remote Chaktraghatti village of Barahakshetra managing an ambulance during health emergencies have become a matter of far cry.

In villages, this is everybody’s problem.

Ganesh Rai, a local of Baguwa, had to take his 73-year-old cancer patient mother to Dharan on a tempo seven times when Covid-19 halted public transportation.

“I had to take my mom to the hospital twice a month but couldn’t get an ambulance during lockdowns,” said Ganesh, “It was quite painful to take her to hospital on a tempo during the period of health emergencies.”

Ganesh, who lost his mom in November last year, often thinks she could live for a longer time if a comfortable ambulance was on standby in the village.

Hem Rai, another local from Baguwa, had to lose a 27-year-old wife because of not having an ambulance. “She complained of a stomach ache all of a sudden in the night. I searched for an ambulance as her condition was becoming more serious,” he recalled the seven-year-old incident, “Doctors declared her dead soon after reaching the hospital. The situation hasn’t changed yet.”

Barahakshetra, a municipality of 77,565 population, extends over 223 square kilometers. The municipality known as the largest local government in Sunsari district doesn’t have even a single ambulance.

Few privately run ambulances charge excessively high fees from service seekers and are not reliable in providing timely service. One has to pay five to seven thousand to take patients from Suryakunda to Dharan, a 19-kilometer road section.

“We have to pay a highly excessive fee to get ambulance service,” said Hem, “Getting timely ambulance service remains yet another challenge. The municipality has no hospital nor does it have ambulances to take patients to the hospital.”

Primary Health Center, Chatara.

Nirmala Majhi, a local of Barahakshetra-2, Sunsari, didn’t get the ambulance to take his mother-in-law to the hospital when she was suffering from chronic throat ache and fever. She was taken to Chatara Health Post which had later referred family members to take her to well-equipped hospitals. Economically poor Nirmala wasn’t able to afford a private ambulance so she tried to commute on a private vehicle. That also didn’t work. Nirmala returned home together with the ailing mother-in-law.

“Ten minutes after reaching home she breathed her last,” Nirmala lamented, “Much had been talked that Singha Durbar will arrive at all courtyard once local governments are in place under new federal set up but that proved false for us. Elected people’s representatives get allowances just for attending meetings. Who cares for people like us? It doesn’t matter whether we are dead or alive?”

This municipality has no ambulance. Locals have to pay a hefty fee to take patients on an auto-rickshaw in case of health emergencies. Getting an auto-rickshaw is also not easy when an emergency arrives.

Krishna Chamling, a local of Barahakshetra-3, Punarbas, fainted all of a sudden and fell on the ground. Locals tried to take him to the hospital but he collapsed before reaching the hospital while being taken on an auto-rickshaw, according to his friend Jitendra Rai.

“Perhaps, he could survive if he was taken to hospital in time,” said Jitendra.

Just two months ago, a woman from Aandramath of Barahakshetra was suffering from labor pain. The woman from a poor Mushahar family had no money to hire a vehicle. She breathed her last before reaching the hospital. “Husband was away from home for a menial job. No other family members were at home,” said a villager adding, “She died at home while talking about ways to collect the money required for transportation.”

Chakraghatti Municipal Hospital.

Depressed by the loss of the wife, the husband has already left this village together with children. Health offices in Chatara and Madhuban and another one established at the municipality are often overwhelmed. Patients from bordering Udayapur, Bhojpur and Dhankuta districts also arrive at the Chatara health office. Due to the increased number of patients, Chatara health office provided emergency and delivery services round the clock whereas OPD remains open from 8 am to 8 pm.

Dr Anil Giri of Chatara Health Post says 20 percent of the total patients approaching health posts need either ICU or NICU. The health post refers such critical patients to major regional cities namely Dharan and Biratnagar.

“Sadly, we don’t have well-equipped ambulances to transport critical patients to big hospitals,” said Dr Giri.

Chatara health post is a nodal health office for those injured along Dharan-Sindhuli-Hetauda and Rupnagar-Chatara-Nadaha Road sections. The hospital has no ambulance whereas it has to refer critical patients immediately to other hospitals.

“This center requires both an ambulance and coffin carrying vehicle,” said Dr Giri.

In 2014, a woman from Tamrang of Dhankuta was admitted to Chatara health office. She died at the hospital after failing to arrange a vehicle to go to Dharan. “It’s been eight years since she died in the absence of an ambulance. Yet, nothing has been changed so far,” said Lamka Man BK, a Maoist leader, who is also a member of Chatara Health Post Management Committee, “Municipality lacks life-saving ambulances.”

Hospital authorities blamed the lack of resources behind their failure to buy an ambulance. “Health post is not in a position to buy an ambulance on its own. We are already tired of knocking on the doors of municipality and district offices. Our voices remain unheard.”

Growing private business

Altogether six privately run ambulances are in operation in this municipality. These ambulances are accused of eying on profit-making business rather than serving critical patients.

Lal Kumar Tamang, chief of ward no 2, says most privately run ambulances have flouted health criteria i.e., installation of oxygen cylinders and arranging first aid equipment. Neither are patient-friendly.

Ambulance of Prakashpur Health Post that has been out of operation.

“Privately run ambulances aren’t available in case of any health emergency. If available by luck, they seek an unaffordable fee,” he said.

Because of this, service seekers prefer to travel on public vehicles. Sharada Khadka, 48, a heart patient travels on a public bus to reach BP Koirala Health Institute, Dharan. “Since ambulances are not available, we travel on public transportation to reach hospital risking life,” said Sharada.

Sharada, who is also the former chief of Save the Heart, says at least five heart patients from her village are travelling on public vehicles on a regular basis.

Patients have to frequently reach the hospitals for treatment. “Ambulance ordered from Dharan was delayed by an hour. By then, the patient collapsed.”

Privately run ambulances, which often lack even a torch, are often to carry students to goods to make a profit.

Lal Bahadur Rai, principal of Prakashpur-based Sunrise English Boarding School, said two people, a male and a female, died two months ago because of not getting timely ambulance service.

Principal Rai himself nearly lost his son in absence of an ambulance. “None of the privately run ambulances refused to take my six-year-old son to hospital when he was suffering from pneumonia. He was taken to hospital only when we warned them of vandalizing ambulances. Luckily, he survived.”

Unaware people’s representatives

The municipality has failed even to manage an ambulance whereas it has principally endorsed the motto of ‘Prosperous City, Happy People, Quality’.

Principal Rai thinks not having an ambulance is the height of irresponsibility. “Elected people’s representatives don’t care about the people. We are also responsible for this mess as after the election we forget everything unless the next round of election approaches.”

Hari Parajuli (R) and Dilmaya Raut.

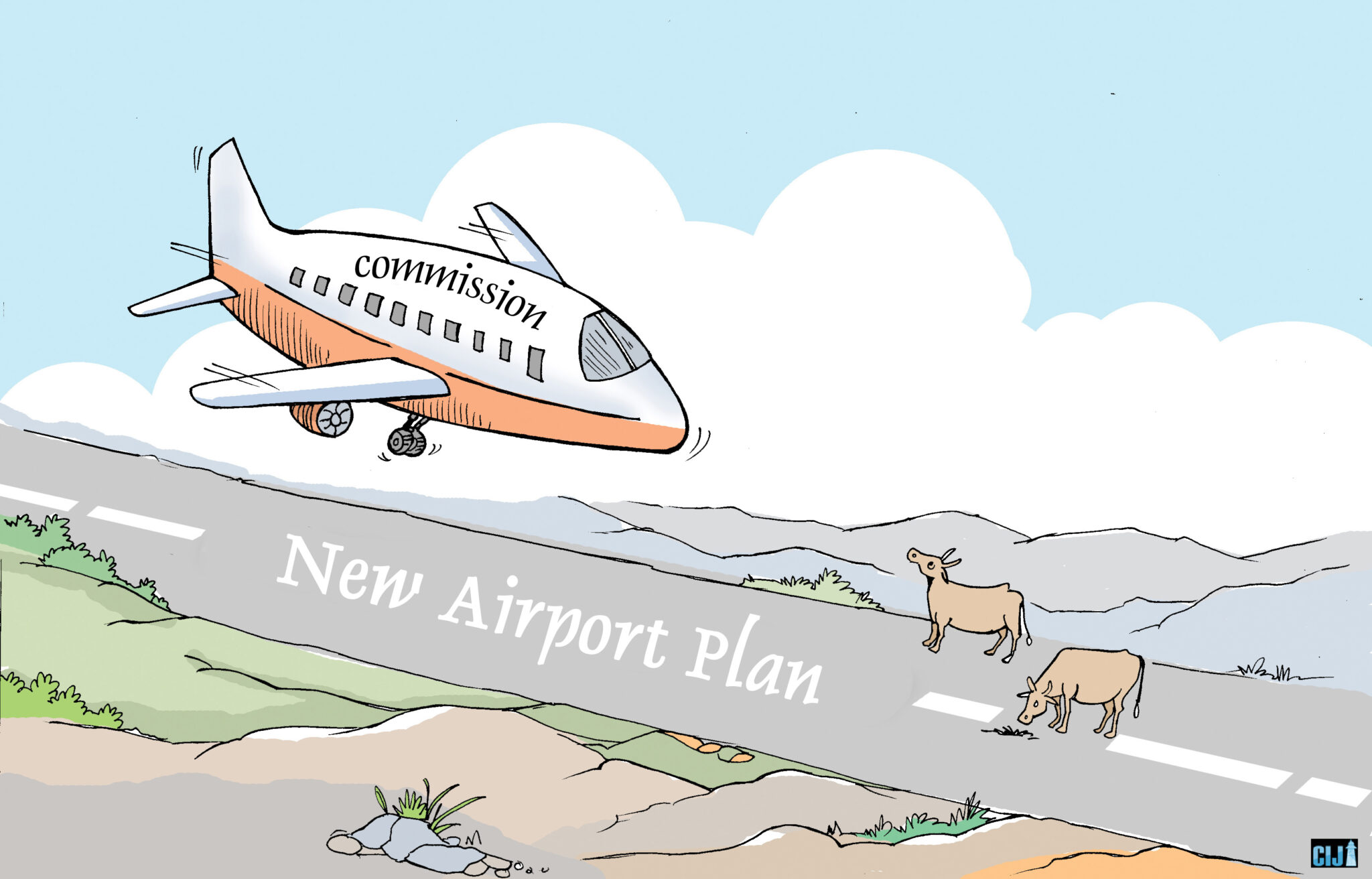

The municipality has unveiled an annual budget of Rs 1.58 million for this fiscal year. As per financial details mentioned in the municipality’s records Rs 10 million has been allotted for facilities of office bearers, Rs 550,000 for their allowance, Rs 2,800,000 for field allowance, Rs 1,380,000 for visit, Rs 200,000 service and consultancy, Rs 2,400,000 for miscellaneous and Rs 150,000 for programs.

The budget has been spent in other areas. More than 20,000,000 has been spent on research and consultancy on animal husbandry and floriculture. About Rs 3400,000 was spent in repairing religious sites. The health sector is largely ignored even while the municipality allocated more than Rs 1 billion as its annual budget.

Disabled people are also miffed with the inaction of the municipality. “My body below the waist is motionless. My husband crawls. No caretakers at home except elderly parents. Local government, whom many say is the nearest Singha Durbar, didn’t care about us,” said Dilmaya Raut, a disabled who married another disabled Hari Parajuli.

The couple needs an ambulance even to reach the health office, which lies ten minutes away. Poor people aren’t able to afford an ambulance.

Jitendra Rai, a local leader of the main opposition CPN-UML, blames elected people’s representatives aren’t serious about buying ambulances for locals. “If you ask the ward office about their failure to buy ambulances it blames the municipality, and then municipality to provincial and federal governments.”

Bijaya Acharya, a Female Community Health Volunteers in Prakashpur said pregnant and serious patients have to struggle to reach health offices. “Road is not good. Cases of pregnant women giving birth to children or serious patients dying on their way to hospital are too common.”

Mohan Subedi, chairperson of City Hospital Management Committee, Chakraghatti, complained his proposal to arrange ambulances was never heard when he raised this issue at the municipality meeting.

Opposition leaders say that Mayor Nilam Khanal deliberately allocates less budget on their plates when they propose a budget for good work. “Not releasing enough budget to buy an ambulance even when the municipality unveils more than Rs 1 billion budget is not good. It’s nothing other than the height of irresponsibility and negligence towards the people,” said Uddab Prasad Pokharel, ward chief of Barahakshetra ward no 6.

Nilam Khanal, Mayor

Mayor Nilam Khanal claimed he has been working hard to arrange resources from the federal government to buy an ambulance and hoped to get it by the end of mid-January. Health officials, locals and people’s elected representatives aren’t convinced with the mayor’s words.

They blame the mayor for not initiating the process to procure an ambulance.

Other municipalities in the district have two ambulances. For example, Dewagunj has three ambulances. Two of the total three ambulances donated by India are in operation.

Another neighboring municipality Koshi Rural Municipality has two ambulances. Haripur and Laukahi rural municipalities, which have less than 44000 population, have two ambulances each. So is the case of Bhamari Bazaar and Satterjhoda of Gadhi Rural Municipalities whereas their local population is less than 35000.

Shree Prasad Yadav, the chairperson of Gadhi Rural Municipality, said his government has been arranging free ambulance service for 600 locals identified as disabled and economically poor in Bhameri and Satterijhoda.