Rudra Pangeni: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Baburam Pandey, a section officer in the Ministry of Land Reforms, joined Nepal’s civil service as a non-gazetted officer seven years ago. The 31-year-old, who hails from Arkhale Village, Gulmi district, lives with his wife and five-month-old son in a one-bedroom rented flat in Kirtipur. Pandey spends Rs 10,000 (28 percent) of his monthly income on house rent. He often finds himself thinking that he will spend his whole life as a tenant. “I don’t have savings,” he says. “Even if I sell my ancestral property, I don’t think I can buy a piece of land [in Kathmandu].”

From government officers like Pandey and private-sector professionals to working class Nepalis in the capital, everyone struggles to secure a house in Kathmandu. The exorbitant cost of property in Kathmandu is inextricably tied to the inflated price of land in the capital. That’s the source of the problem plaguing the capital’s real estate market.

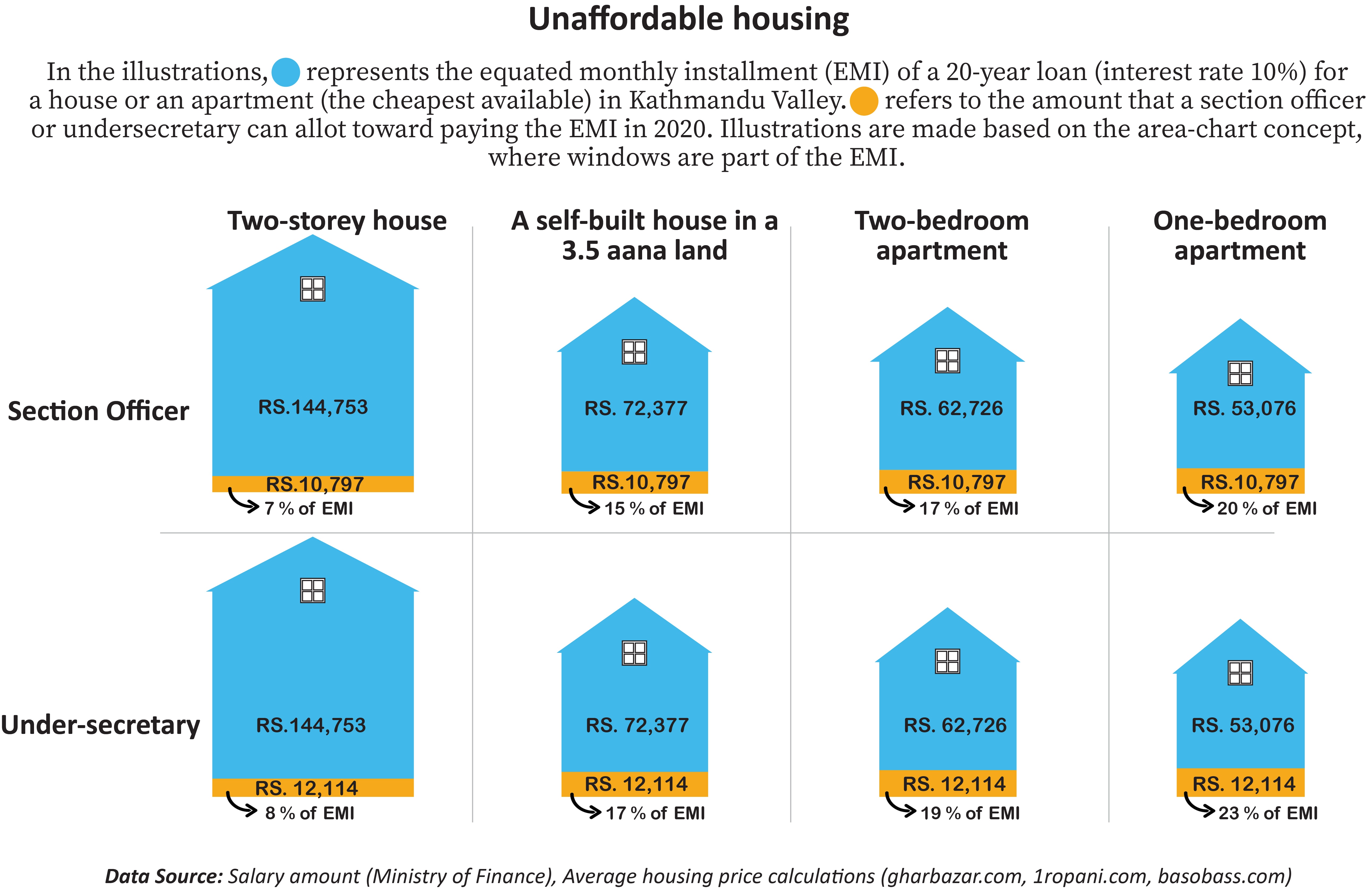

According to Leilani Farha, the former UN special rapporteur on adequate housing, it’s universally accepted that a maximum of 30 percent of an individual’s or a family’s income should go towards housing costs. But renting or buying a house in Kathmandu and in Nepal’s other urban centres costs more than an arm and a leg.

That’s not the case in most countries, where better regulated markets enable people to buy a house or a flat with a monthly installment (on an 18-20 year loan) not exceeding 25 to 30 percent of a citizen’s salary. In Nepal, according to the latest household survey by the Central Bureau of Statistics, urban households spend about 45 percent of their income (Rs 431,337) on foodstuff and 18.7 percent on rent alone. The survey, however, does not include questions related to a family’s monthly installment for buying a house or a flat.

Infographics by Pramod Acharya

Professionals like Pandey also face difficulty in buying a home through bank loans. Banks don’t issue home loans to people in his income bracket, as their salary doesn’t meet bank requirements. “Housing affordability should be set against household income, and no one should have to pay more than 30 percent of their income towards affording a house,” Farha told CIJ Nepal. “This is a widely accepted figure. Housing costs should not be based on what the market can accommodate. Rather, they should be based on how much households can pay in relation to their overall income.”

But Kathmandu’s real estate market operates in opposition to that logic. “Almost all professionals in Nepal don’t have the means to afford Kathmandu’s real estate rates,” says Kishor Thapa, a housing expert and former secretary. “How many years does one have to work to buy a plot of land? When can they finally build a house? People’s minds are consumed by these questions because housing is an essential need.”

It’s also universally accepted that a person or a family should be able to build a house with two years of their income. But in Nepal, a government officer can only buy the cheapest one-bedroom flat (Rs 5.42 million) available in the market with 9 years of his salary (with an average annual salary increment of 9.18 percent). Even if both husband and wife work for the government, they would still struggle to buy a house here. Likewise, a large number of private-sector employees cannot afford a house. Except for those in the upper echelons of some corporate houses, the average private-sector professional’s annual income is not much higher than that of government employees. According to Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), among Nepalis with a savings account, the average savings is Rs 40,700 per year. In the urban areas, such account holders save on average Rs 60,400 per year

As for the poor in Kathmandu, they cannot afford to rent the most basic flat even with 25 percent of their income. Even the country’s doctors and engineers, who are well paid, struggle to buy a house or a plot.

Four years ago, Nepal participated in the Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development in Quito, Ecuador. The government’s report, titled ‘Inclusive Cities and Uplifting Communities’, said the number of families in Nepal’s urban areas who could not afford a house was increasing owing to rising real estate prices. According to former secretary Thapa, the urban housing problem has impacted the working poor especially hard. He says the government’s failure to introduce new policy on housing could ultimately result in homeless people sleeping on the streets, with their numbers looking to rise in a few years.

But while the government’s inability to regulate the sector has been a bane for homebuyers and tenants, it has proven to be a boon for real estate players. That’s primarily because land, which is a natural resource, has become a lucrative commodity in urban Nepal. As a result of the government’s regulatory failures, many people have turned to land-dealing to make money. Land is such a money-making commodity that today industrialists are focusing on the real estate sector, over their own sectors.

Sujeev Shakya, chairman of Nepal Economic Forum, an economic research organization, says, “Whether it be a school or a hospital, a hydropower company or a bank, enterprises now focus on how to make money quickly. To do that, they turn to real estate. Rent-seeking, which is the practice of making money off ventures that do not help the overall economy, has been detrimental to the culture of entrepreneurship in Nepal.”

That issue, however, doesn’t seem to bother politicians, who are themselves involved in the real estate market. The infamous Baluwatar scam, which saw big-name politicians colluding with real estate agents, brought to light the nexus between Nepal’s political elite and the land mafia. And because everyone, from the average Nepali to tycoons, knows that they can quickly make money off real estate, everyone wheels and deals in property when the chance presents itself. It’s thus no surprise that Kathmandu has turned into a chaotic concrete jungle.

But why is land being exploited in such a manner? Outlined below are the major factors.

Profit without hard work

According to Sujeev Shakya, most sectors are taxed at a very high rate, even as land dealers continue to be taxed at a much lower rate. The corporate sector, for example, has to pay a 25 percent tax on profits. The government levies a 10 percent tax for every Rs 100,000 a professional or job holder earns per year, on top of the minimum income tax threshold of Rs 400,000 (for an individual) or Rs 450,000 (for a married couple). Similarly, the minimum tax rate for an annual income exceeding that amount is 20 percent. And home builders pay a 25 percent corporate tax on the sale of their units.

But land deals are not taxed as heavily. This encourages real estate players to buy and sell land, rather than build housing units, because they can pocket a larger portion of the profits made. The capital gains tax on land sales is capped at 5 percent. Unsurprisingly, most professionals would rather become land dealers than devote their life to working a steady job.

A conduit for money laundering

The real amount involved in a land transaction is never reflected in government documents. Buyers spend large amounts for a plot, but they register only a fraction of that at the Land Registration Office. This helps them evade taxes. Because it is so easy to circumvent the sector’s rules, land deals have also become conduits for laundering black money. “One of the main reasons behind the increase in real estate prices is that people who make their money illegally invest in the real estate sector,” says economist Chandra Mani Adhikari.

On April 21, 2015, speaking at a programme in Rupandehi, Kewal Prasad Bhandari, the erstwhile Director General of the Department of Money Laundering Investigation (DMLI) had said, “The mafia have bought expensive parcels of land but registered them at lower prices in order to launder ill-gotten money through real estate deals.”

Due to the absence of an integrated database of house and land ownership, the government itself is in the dark about the volume of land an individual owns.

Transactions involving large amounts of money actually violate the law. Conducting cash transactions of above Rs 1 million is illegal in Nepal (the Department of Money Laundering Investigation can confiscate the money used in such deals). Nevertheless, people still buy and sell land using cash. According to Sitaram Dahal, President of the Nepal Legal Professionals’ Association, cheques making up some of the transaction amount are presented at the Land Registration Office, while the part of the deal conducted in cash is not registered.

Reports of such illegal acts, some involving public figures, are already part of public knowledge. A Nepal Weekly article of 2018 says, “Former Chief of Army Staff Rajendra Kshetri bought a house in the Dhobighat neighbourhood, Lalitpur, by paying Rs 20 million through an intermediary, while eschewing the formal banking process.” No action has been taken against him so far, and only recently did a parliamentary committee direct the Department of Money Laundering Investigation to investigate Kshetri’s property.

According to land buyers, even registered real estate agents, to avoid scrutiny, ask that they be paid in cash, or in cheques amounting to below Rs 1 million. Banks are supposed to report transactions of Rs 1 million or above to the NRB’s Financial Information Unit (FIU). Likewise, real estate companies and Land Registration Offices have to report to the FIU transactions above Rs 10 million. After analyzing their data, they are also required to report suspicious transactions. However, Rup Narayan Bhattarai, DLMI’s director-general), has denied getting any information of suspicious transactions in the real estate sector.

“Because the Land Registration Office and other relevant agencies have not filed reports, we haven’t been able to investigate the real estate sector,” says Bhattarai.

But a mechanism launched in 2013 does allow the FIU to monitor bank transactions of a person or organization. Besides, banks also require that for transactions exceeding Rs 1 million or above clients furnish details about their revenue sources.

Owing to this provision, public figures such as politicians and high-ranking officials resort to diverting their money to cooperatives, instead of banks.

“They authorize the directors of cooperatives to buy properties under the director’s name so that they (politicians and high-ranking officials) can make a profit without inviting scrutiny,” says economist Keshab Acharya.

A former FIU official, seeking anonymity, says, “Most government officials do know that illegal income gets diverted to the real estate sector.” But because officials too are exploiting the gaps in the regulatory mechanisms, the authorities are in no hurry to help design remedies.

Banks and the real estate sector

Generally, loans provided by banks, which come from their clients’ savings, should increase a market’s productivity and create employment. But that’s not the case in Nepal–even though an NRB directive says that commercial banks should disburse at least 10 percent of their loans to agricultural initiatives and a combined 15 percent to the tourism and energy sectors. But banks don’t report the exact figures for such priority-sector loans, and mislead the NRB.

On February 9 2020, Naya Patrika Daily reported that only 17 percent (the minimum requirement is 25 percent) of the loans issued by banks went towards productive sectors. To make matters worse, bankers have been lobbying the government to avoid action after the NRB fined a few banks for failing to meet the requirement last year.

“If my bank can invest in, say, hydropower, I am able to borrow another category of loans from another bank for reporting purposes, only for meeting the minimum credit flow in the agriculture or tourism sector,” says Bhuwan Kumar Dahal, President of the Nepal Bankers’ Association (NBA), an umbrella organization for Nepal’s banks.

From Left to right: Finance Minister Yubaraj Khatiwada, Former Finance Minister Ram Sharan Mahat and Governor of Nepal Rastra Bank Maha Prasad Adhikari. They have invested their savings in real estate in order to make money. Photo credit: Ministry of Finance, Nepal Rastra Bank and Republica Daily.

Two years ago, Finance Minister Yubaraj Khatiwada issued a white paper on the state of the country’s economy. “The banks have issued loans not to the government-designated priority areas, but to areas that contribute less to income generation and employment,” said Khatiwada. Seventy-six percent of the loans were disbursed against real estate and movable property, and project financing was rare, according to him.

The money that companies purportedly borrow for investing in other enterprises–industries, schools, hospitals–is also being funneled into the real estate sector, according to Shakya. “Many enterprises are not making huge sums of money,” says Shakya. “These enterprises also divert their business loans into land deals, to make money overnight.”

Nara Bahadur Thapa, who recently retired after serving as executive director at NRB’s Research Department, points to the government as the main problem. “This is not the banks’ fault. It results from the government’s failure to boost economic activities via mega development projects and so on,” he says.

But banks, too, prefer to loan out money for land deals–because there is little risk involved for them. Banks lend amounts worth only one-third of the market value of the land their client wants to purchase. If their client fails to pay back the loan, the ban

ks can auction off the land. Furthermore, banks don’t care whether the loan they gave was used for the purposes the borrower outlined in the loan agreement. The Office of the Auditor General, in its annual report, has warned that action should be taken against banks for not tracking how their loans are used. Deputy Auditor General Ramu Dotel says, “Loans taken out for other purposes routinely get diverted to real estate deals.”

The NBA’s Bhuwan Kumar Dahal admits that banks are complicit to some extent in helping increase real estate prices. It all stems from practices that involve land as the cornerstone. “Clients don’t pay off their loans if we lend without collateral. That’s why we require land as collateral,” he says. In response to the banks’ preferences for land as collateral, many entrepreneurs first invest in land before setting up their business. For the entrepreneurs, this makes sense on two counts: one, the price of their land will continue to go up no matter what; and two, even if their business fails, the increased value of their property will help offset some of their losses. But this manner of doing business also helps increase overall market demand for land. Ultimately, this artificially inflated demand raises the price threshold for land everywhere.

Thus, among those who work in the real estate sector, it’s land dealers who are making a killing. Bhesh Raj Lohani, general secretary of the Nepal Land and Housing Developers Association, says, “Of the Rs 162 billion invested in the real estate sector until mid-January of this year, the housing sector has only received 10 percent of those loans. The rest has gone to unregistered agents who make a profit by merely trading plots.” According to the NRB, Rs 255 billion has been invested this year in personal home loans. The total investments related to houses and flats account for only 12 percent of all the loans disbursed to the real estate sector.

Earlier, in 2011, the NRB had capped real estate lending at 25 percent, to prevent a possible financial crisis arising from the banks’ over exposure (some up to 65 percent) to the real estate sector. In response, some banks started masking the loans they issued to that sector by packaging them as other types of loans.

There have also been instances where the banks themselves have colluded with the land mafia on shady land deals. For example in a case that was widely covered by the media recently, 21 banks loaned out a total of Rs 2.41 billion to the land mafia, who presented property inside the Prime Minister’s residence, in Baluwatar, as collateral.

The lure of land dealing is also adversely affecting development activity across Nepal. Advances released by the government to contractors for procuring construction material, for example, often get invested in real estate, according to Kishor Thapa, who is also a former Urban Development Secretary. “That’s why not a single project gets completed on time,” he says.

The well-to-do invest in land

Government officials and public officials often talk about how investing in sectors such as agriculture, tourism, and hydropower will increase productivity and generate employment. But many current and former ministers, who champion the need to invest in productive sectors, have themselves invested in real estate.

An aerial view of Kirtipur that shows sprawling urban center in Kathmandu valley. Photos: Rudra Pangeni

According to the property details furnished by Finance Minister Yubaraj Khatiwada on April 16, 2018, he owns two houses in Kathmandu’s Bishalnagar neighbourhood (a 5 anna and 14 anna plot under the land certificate of his wife Kamala Khatiwada). Besides, the couple owns 24 anna of land, worth Rs 9.5 million, in Changunarayan, Bhaktapur. They also own land in Jhapa and Dolakha.

Nepali Congress leader Ram Sharan Mahat, a former finance minister, who held the portfolio six times, owns houses and plots in various locations. According to the property details he released in 2014, when he was Finance Minister, he owns a two-and-half story bungalow in Bansbari, on the outskirts of Kathmandu. His wife, Roshana Mahat, owns a 1,761 square foot flat in Baluwatar. He also owns three ropanis, of 11 anna of plots, in Budhanilkantha, Chapali, and Dhapasi. In addition, he owns 12 ropani and 7 anna of land in Kavre and 3 ropani of land in Nuwakot.

Governor of the Nepal Rastra Bank Maha Prasad Adhikari has also poured his savings in real estate properties. After becoming the governor, he released his property details on May 2020, which showed he owns a house built in 6 Aana land in Sainbu Lalitpur. Likewise, he owns a total of 12 ropani land in Chhampi and Sainbu Lalitpur and he is also owner of 3 bigaha land (reward and inherited property) in Jhapa district. In addition to that he has stake in different financial institutions and hydropower companies worth Rs 15.7 million.

Former Deputy Prime Minister Gopalman Shrestha released his property details on August 6, 2017. According to the details, he owns seven houses in Kathmandu, Rupandehi, Syangja, Pokhara, and Lalitpur. He also owns a total of 22 anna of land in Kalanki, Tinthana, and Thankot, Kathmandu, along with plots in Rupandehi and Syangja.

Politicians are not the only ones investing in real estate. Well-paid professionals from the corporate sector and Nepalis who work for foreign donors also prefer investing in real estate. They buy houses and flats in expensive housing colonies– not to live in them, but to earn a profit. A Bhaktapur resident who bought a flat for more than Rs 20 million at Cityscape Towers, in Hattiban, Lalitpur, says, “We invest in property because it’s a safer investment than starting a company. We wouldn’t be able to monitor the activities of our business, if we were to start one, because we spend most of our time on our job.”

People are not interested in bank savings either, because the interest rate offered is often lower than the inflation rate. An NRB study on real estate financing published nine years ago shows that the demand for real estate also increased due to lack of investment opportunities.

Former Finance Secretary Rameshwar Khanal says, “When the economy does not expand, it is common for people to invest their accumulated wealth in real estate.”

This practice, wherein large sections of the middle and upper middle class invest in real estate, is also a major driver for making Kathmandu’s land rates among the most expensive in the world.

Politicos and the people turn real estate brokers

A popular Nepali song, ‘Jagga Dalal’, by Rabin Lamichhane and Sita Shrestha, includes these lyrics:

I can’t even light my kitchen stove with my salary

I can’t live off my business

So I too will become a land broker now

Because the work is easy and the money plentiful

This folk song says a lot about the popularity of real estate brokerage as a profession. All you have to do as an agent is show a plot to prospective clients and get a commission on the sale, without your having to invest a single rupee. And should you choose to hide your activity, you don’t have to pay a tax on your earnings.

Dealing in land is so lucrative it’s impacting sectors that have nothing to do with land deals. In an interview with Barhakhari, veteran artist Nir Shah said the quality of Nepali films started to deteriorate after land brokers began investing in films. Flush with quick money, a handful of real estate brokers got into producing films, to garner name and fame. On the flipside, more than a dozen artists, frustrated with their low returns from films, and lured by the prospects of big profits, started to engage in land deals.

It is extremely easy for anyone to become a broker. In its budget speech two years ago, the government had made it mandatory for real estate brokers to register themselves, but that provision has not been implemented yet.

Furthermore, elected officials and politicians, far from helping rein in the sector, oftentimes intervene in the most unscrupulous fashion. Twelve years ago, Pushpa Kamal Dahal, then Maoist chairman, addressed an election rally in Bharatpur, where he called for shifting Nepal’s capital to Chitwan. The district’s real estate prices have since increased almost 25-fold. “After his speech, people from Kathmandu rushed to buy plots in Chitwan,” says Thapa. “Some plots were bought and sold many times a year.”

Measures to control land prices

One way to control prices is to stop the quick buying and selling of land. The government has levied a profit tax of 5 percent on land that is resold within five years, and 2.5 percent on land that is resold after five years. But the taxes haven’t done much to control land prices. “The tax rates for those who quickly sell a plot should be higher,” says Thapa. “And if we place a five or seven year moratorium on sale after purchase, land will no longer be treated as a commodity.”

Another option is to control and regulate how banks extend credit to people. Banks should not be allowed to issue loans when people present as collateral land with an inflated value. Former Finance Minister Surendra Pandey says, “If banks stopped lending on the basis of land put up as collateral, the price of land would go down automatically.”

Such regulations would help increase investment in productive sectors. But this would be possible only if the banks first focused more on financing projects and if the NRB regulated the banks effectively. The government can also control real estate prices by imposing higher taxes on inherited property and on the properties that people own besides their primary residence. The lack of taxes on inherited property helps people accumulate property, according to economist Shakya.

The Constitution envisions a socialist-oriented economy, in which every citizen is able to afford housing. Experts say the government should help turn that vision into reality. “The government could integrate plots of land and carry out low-cost schemes for plotting, for example,” says former Secretary Thapa. “Why can’t we do what our neighbours have done?”

Nepal’s real estate sector can only get reformed if the government deals with it with a firm hard. “If the government reformed the overall real estate economy, most Nepalis finally would not have to worry about owning a house,” says Thapa.

Note: 1 ropani is equal to 508.73 square meter or 0.125 acre. Rs 115 is approximately equal to a US dollar.