The Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) in Nepal, initially tasked with combating corruption and ensuring good governance, now navigates through the sway of diverse interest groups and political pressures, resembling a lost traveler.

Tara Chapagain |CIJ Nepal

Lokman Singh Karki proved to be a disruptive civil servant. Initially appointed as under-secretary of the palace service through a royal decree on July 24, 1984, he was subsequently transferred to the civil service following the restoration of parliamentary democracy in 1990. On September 19, 2005, he was eventually promoted to the position of the government’s chief secretary.

Until May 11, 2006, Karki served as chief secretary. Subsequently, he was appointed to a newly established position, chief officer, at the National Planning Commission for a two-year term.

Until May 11, 2006, Karki served as chief secretary. Subsequently, he was appointed to a newly established position, chief officer, at the National Planning Commission for a two-year term.

Adept in wielding and misusing power, Karki remained indispensable even in the republican system, with political parties relying on him for specific roles. In the first week of May 2006, the government nominated him as the head of the constitutional anti-corruption watchdog, CIAA, through political party consensus. Despite his initial appointment, Karki was later ousted as parliament took an extraordinary step, filing an impeachment motion against him.

Amid existing corruption charges, Karki faced accusations from the Raymajhi Commission of abusing power to quell the Second People’s Movement. Despite these allegations, the government appointed him to the National Planning Commission. Subsequently, he was let go with the government merely seeking clarification on the charges. Karki resigned from the chief officer role only after the government reached out to the Public Service Commission, seeking guidance on the dismissal procedure

By that point, Karki had amassed considerable power, shielding him from investigations even after Parliament suspended him. Ultimately, it took a Supreme Court verdict determining Karki’s ineligibility for the position of the country’s anti-corruption watchdog to result in his dismissal

Following Karki’s removal, Deep Basnyat assumed the role of chief commissioner of CIAA. However, Basnyat found himself implicated as one of the primary accused in the notorious Lalita Niwas case, involving 175 individuals, during Chief Commissioner Naveen Kumar Ghimire’s tenure.

The former Secretary at the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure, Basnyat, formulated a proposal to transfer government land to private individuals, encroaching upon the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Land Reforms. Minister Bijay Kumar Gachhadar sanctioned the proposal, presenting it to the Council of Ministers. Madhav Kumar Nepal’s Council of Ministers issued a ‘policy decision’ on the matter. Subsequently, legal action was taken against Gachhadar, Basnyat, and others involved in the process.

Commissioner behind bars

The then Commissioner, Rajnarayan Pathak, faced accusations of engaging in the buying and selling of cases. A video surfaced, showing him involved in a financial transaction under the guise of settling a relationship dispute at Bhaktapur-based Nepal Engineering College. Another video revealed his acceptance of a bribe amounting to Rs. 7.8 million, facilitated by the college president, Lambodhar Neupane, to resolve a land-ownership dispute. Succumbing to mounting public pressure, Pathak resigned on Feb 15, 2019. Subsequently, the authority took action by filing a case against Pathak and Neupane in the special court on March 26, 2019.

After nearly four years, the court delivered its judgment, finding both Pathak and Neupane guilty. They were sentenced to three years imprisonment and fined Rs. 3.9 million each.

Conviction in numbers

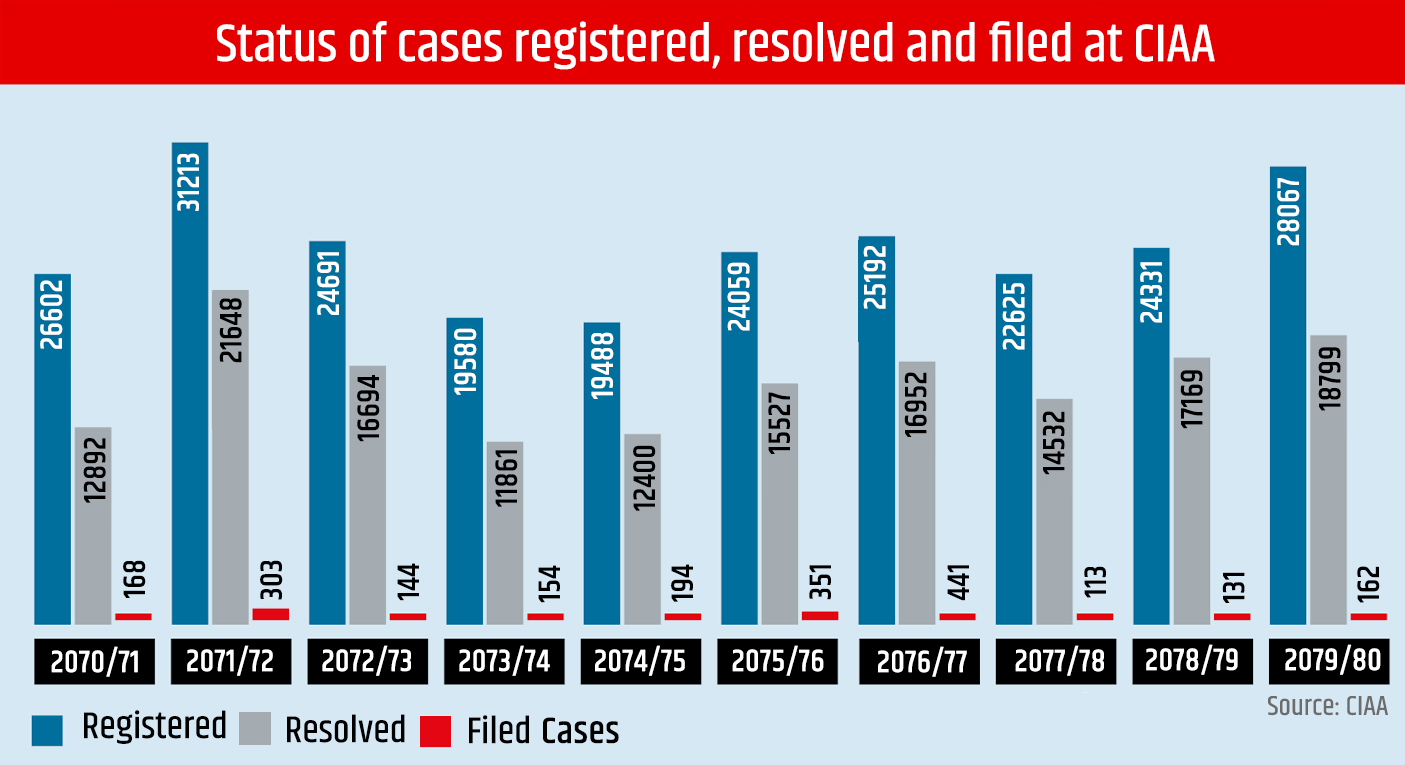

Examining the latest data, in 2021-22, the Authority received 24,331 complaints. Among them, only 131 cases, a mere 0.53 percent of the total complaints, were brought to prosecution.

Numerous complaints lodged with the authority remain pending for extended periods. According to authority sources, “During this timeframe, certain information is leaked, some cases are managed, and only a few eventually reach the court.”

Numerous complaints lodged with the authority remain pending for extended periods. According to authority sources, “During this timeframe, certain information is leaked, some cases are managed, and only a few eventually reach the court.”

Premkumar Rai, the current Chief Commissioner of the Authority, asserts that not all complaints warrant investigation, and the outcomes of every investigation may not merit a trial. He states, “About 10 percent of complaints substantiate a genuine case. These undergo the research process, and ultimately, only 5 percent proceed to a detailed investigation.”

The question that arises is why certain cases are placed on hold. Why does the decision on the same issue vary depending on people’s access and political beliefs?

The Public Accounts Committee of Parliament discovered irregularities amounting to Rs. 550 million in the construction of the Chameliya hydropower project. On December 3, 2014, the committee urged the authority to conduct a thorough investigation and prosecute the case. According to the committee, during the construction of the Chameliya tunnel, the cost per cubic meter for the slope increased from Rs. 14,100 to Rs. 41,500. Despite the committee’s request and the scandal’s connection to the then Energy Minister Radha Kumari Gyawali, the authority did not pursue the case.

Widebody Scandal: In 2016, Nepal Airlines Corporation acquired two planes for approximately Rs. 24 billion. The Public Accounts Committee’s 2018 investigation found the corporation suffered a loss of about Rs. 4.35 billion in the aircraft purchase. The planes were bought through a shell company, with tampered load capacity. Conditions included a requirement for the plane to have flown 1000 hours for intermediary purchases. The procurement process, now under investigation in France and America, became exceedingly opaque.

Image: Sulabh Shrestha, Archive/cij

Point 142 on page 48 of the 2017-18 General Account report states that issuing a Request for Proposal (RFP) for an aircraft with 1,000 flight hours without purchasing directly from the Airbus manufacturer and proceeding with the procurement process is a violation of the law. This contravenes the Public Procurement Act.

The committee alleged negligence in the procurement process and inadequate instructions, recommending action against former ministers Jitendra Narayan Dev and Jeevan Bahadur Shahi of the Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Civil Aviation, along with the then minister Rabindra Adhikari.

The committee additionally proposed taking action against former secretaries of the same ministry—Premkumar Rai, Shankar Prasad Adhikari, and Krishna Prasad Devkota—along with the then managing director of the corporation, Sugat Ratna Kansakar, who played a pivotal role in the procurement process. Despite these recommendations, the authority did not pursue further investigation, and no action was taken against any individuals. The Center for Investigative Journalism has published a comprehensive report on this matter.

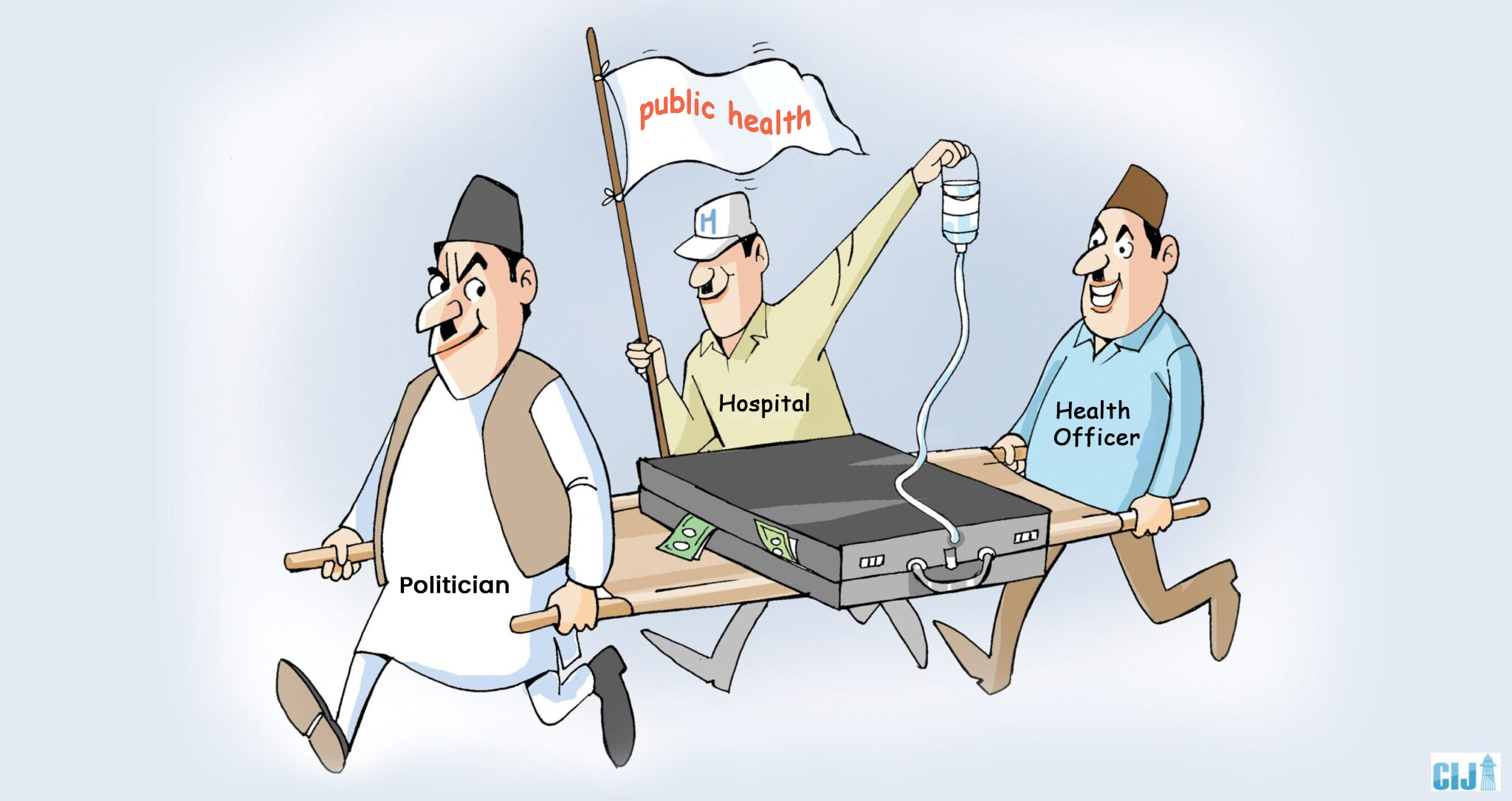

Silence on Exploiting the Epidemic: Amid the Covid pandemic, the Ministry of Health faced accusations of compromising public health by procuring substandard health materials at inflated prices for epidemic control. On March 24, 2020, the government issued a 24-hour notice and entered into an agreement with Omni Business Corporation International (OBCI) Group for the purchase of medicines and health supplies amounting to $139.4 million.

Initially, with Omni’s involvement, substandard health materials were procured at high prices through an agreement with Bidh Lab. Unfortunately, the use of these poor-quality materials resulted in the loss of citizens’ lives. Surprisingly, no action was taken against anyone implicated in this case. The then Director General of the Health Services Department and the Director of the Management Division were transferred, while the then Deputy Prime Minister Ishwar Pokharel, who served as the coordinator of the Corona Control High Level Committee, was transferred to the Prime Minister’s Office. Following this, Pokharel was once again tasked with leading the purchase of vaccines through CCMC.

Despite instructions from the Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee to investigate the then Deputy Prime Minister Pokharel, Health Minister Bhanu Bhakta Dhakal, and others, the authority has halted the case.

During the 2015 earthquake, corruption allegations surfaced in the purchase of tents exceeding Rs. 500 million. The then Urban Development Minister Narayan Khadka was implicated in this case. Departmental action was taken against the then Secretary, Joint Secretary, Director General, and Engineers. However, no further accountability was imposed in this matter.

Ncell’s Profit Remittance: When Ncell applied to the central bank to distribute dividends to its foreign investors, an amount exceeding Rs. 1.92 billion was transferred out of the country through arrangements with the Rastra Bank. Deputy Governor Shivraj Shrestha granted a 100 percent facility for this, despite provisions limiting it to 77 percent. Although the government’s investigation committee found Shrestha guilty, the Cabinet declared him innocent on Jan 16, 2020.

ANFA and Other Cases: As mentioned earlier, the appointment of Lokman Singh Karki as the head of the authority was deemed highly shameful. Besides creating numerous scandals with a controversial image, he initiated lawsuits against his appointment’s dissenters. Conversely, he granted immunity to those with vested interests.

An instance of this is Ganesh Thapa, the president of the All Nepal Football Association (ANFA), who was reportedly involved in irregularities totalling Rs. 581.71 million. The case has been kept pending

He leveraged allegations and complaints against the Maoist leadership, accusing them of corrupting over Rs. 3 billion by presenting fake fighters in combat camps as ‘bargaining chips.’

The corruption case involving the lease to Tea Development Corporation, totaling Rs. 22 billion, was suspended.

The Rs. 13 billion VAT evasion scandal, alleged to involve collusion with employees of the Internal Revenue Department, was withheld

Numerous significant corruption cases exist, wherein the authority either refrained from investigation, faced limitations, or maintained silence especially when the appointing party or leader was implicated

Investigators without investigation skills

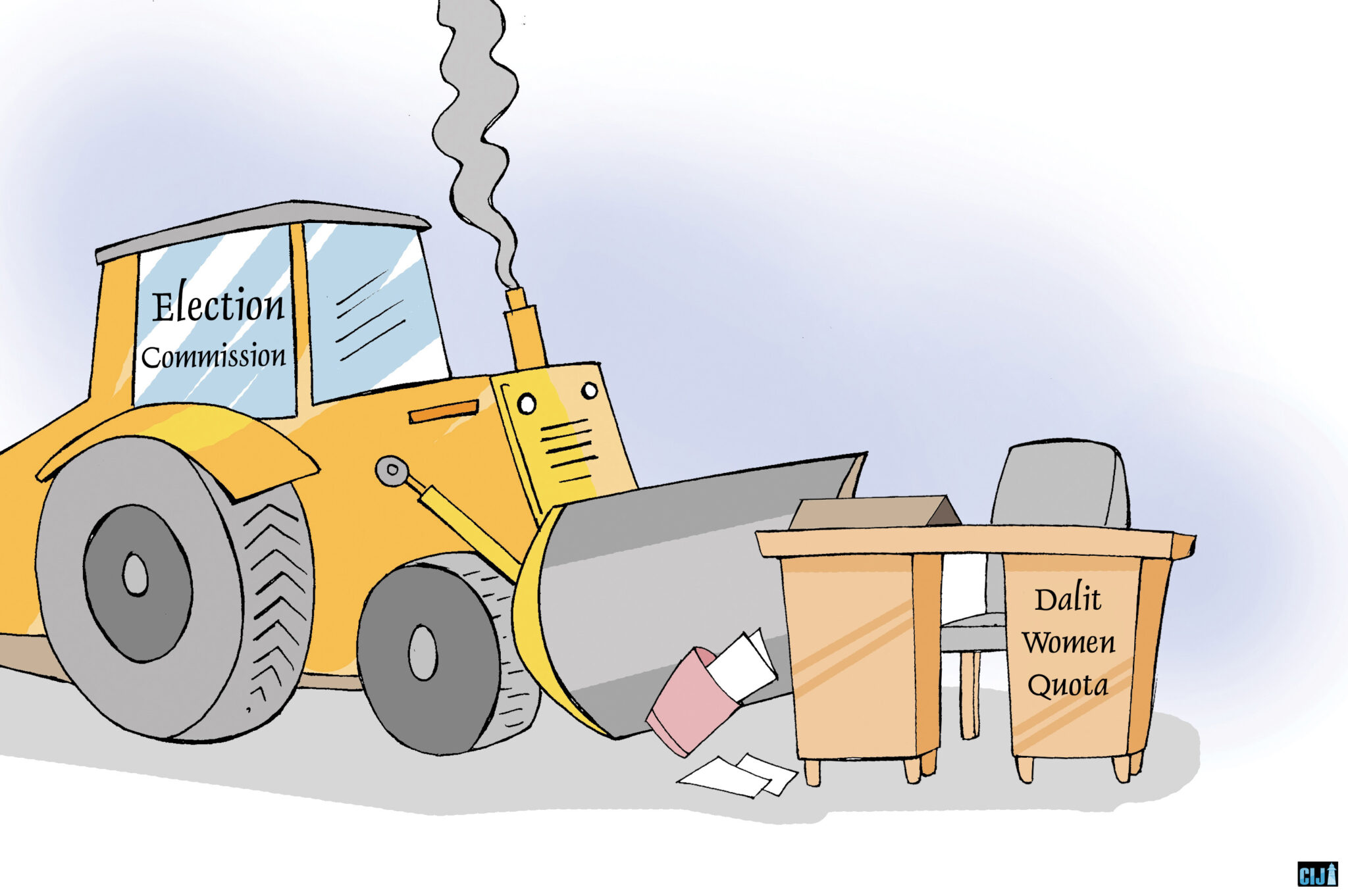

The Constitution of Nepal outlines qualifications for the chief commissioner or commissioner of the Authority, emphasizing qualities like non-membership in any political party, prominence, and high moral character. However, the Constitutional Council, led by the Prime Minister, has consistently appointed officials to the authority seemingly prioritizing their own interests. The decisions of the council, comprising the Speaker and Deputy Speaker of the House of Representatives, the Speaker of the National Assembly, and the leader of the opposition party in the House of Representatives, have not been without controversy.

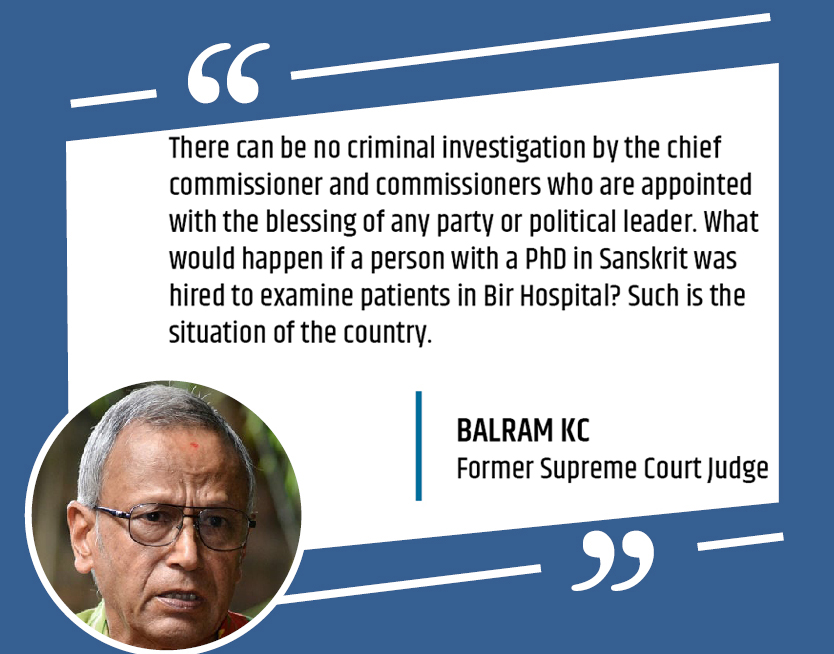

Former Supreme Court Justice Balram KC contends that a criminal investigation by chief commissioners and commissioners, appointed with the endorsement of a political party or leader, is not feasible. “These appointees lack experience in crime investigation. A person who has been a secretary for 58 years will not suddenly acquire expertise in criminal investigation after 58!” KC asserts, drawing a parallel, “What if a person with a PhD in Sanskrit were hired to examine patients at Bir Hospital? Such is the situation of the country.”

Lawyer Bipin Adhikari asserts that the investigation has lost depth as the authority endeavors to extend its reach indiscriminately. “It’s as if the CIAA has to handle everything in our case. Other mechanisms in the country seem ineffective, and it’s up to the CIAA to take action!” Adhikari points out that the CIAA doesn’t need to scrutinize every corruption case; it can focus on both limited and major issues in a thorough manner. He notes that the CIAA weakens when it involves itself even in very commonplace cases.

According to him, the selection of commissioners should prioritize individuals with the highest qualifications.

Advocate Tej Rawal points to weak investigations as the primary reason for the decline in the conviction rate in authority cases. He asserts, “CIAA does not appear to have conducted thorough investigations to confirm the allegations. Additionally, some may have the intention of seeking revenge.” Rawal perceives it as problematic when individuals with a questionable background are appointed to significant positions, emphasizing the need to appoint dynamic individuals, irrespective of their political affiliations.

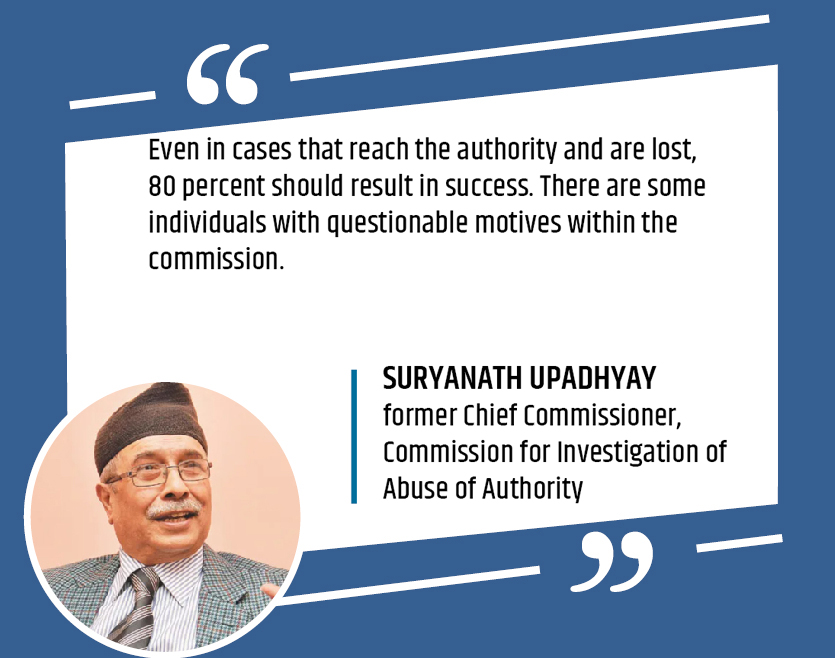

Suryanath Upadhyay, the former chief commissioner of the authority, believes that the authority’s investigations were insufficient to ensure success in all cases. He expressed, “Even in cases that reach the authority and are lost, 80 percent should result in success. There are some individuals with questionable motives within the authority.”

Suryanath Upadhyay, the former chief commissioner of the authority, believes that the authority’s investigations were insufficient to ensure success in all cases. He expressed, “Even in cases that reach the authority and are lost, 80 percent should result in success. There are some individuals with questionable motives within the authority.”

Gauri Bahadur Karki, the former president of the special court, emphasizes that the strength of a case lies in the evidence provided. He stated, “Filing a case alone is not sufficient. Comprehensive research is essential to gather evidence. In case of a loss, there is the option to appeal.”

Former Attorney General Yuvraj Sangraula suggests that the authority’s prosecution efforts have been ineffective. He contends that due to unaddressed corruption cases, there have been more losses, stating, “Prominent corrupt individuals tend not to lose cases. The authority often files cases for appearance only, lacking thorough investigation and strong evidence collection.”

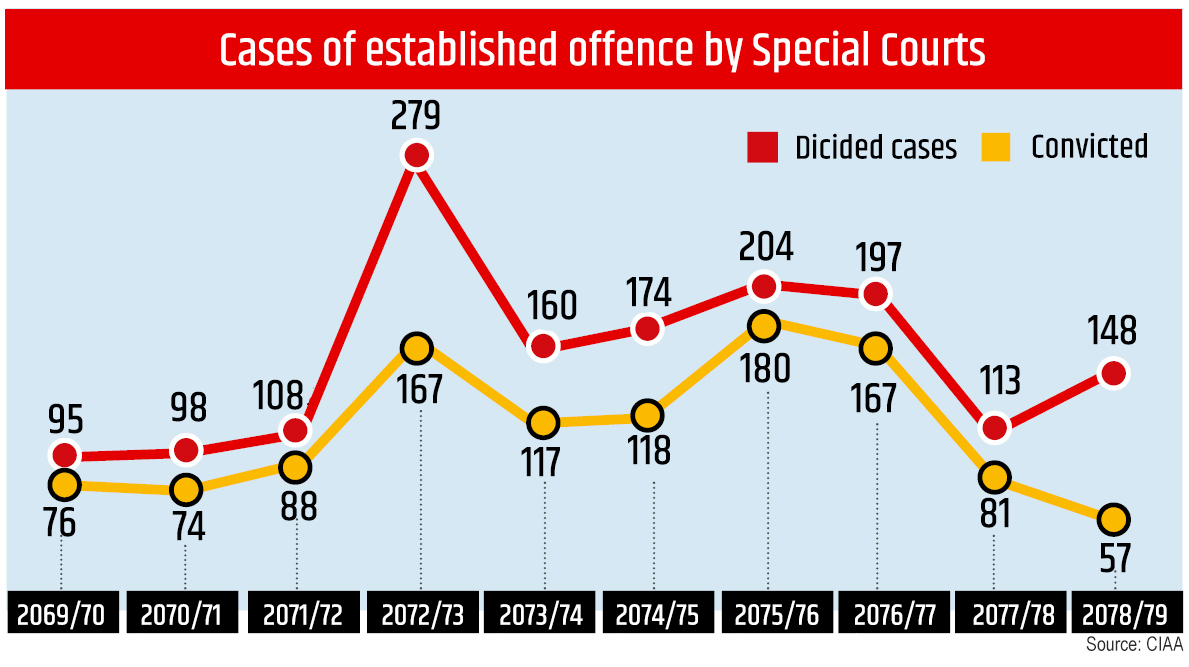

Rising cases, falling convictions

According to the Abuse of Authority Investigation Commission, 88.24 percent of corruption cases filed by the commission in the financial year 2018-19 were proven. However, by 2021-22, this figure has declined to 38.51 percent. In other words, 61.49 percent of the corruption cases prosecuted by the Authority have not resulted in conviction. Yet, there’s a concern with the authority’s data interpretation. Even if the authority files a case with 50 people as defendants and only one of them is convicted, the authority counts it as a 100 percent success.

Let’s consider an example. In the financial year 2022-23, the special court has rendered judgments in 341 cases filed by the authority. Among them, the Commission has appealed in 237 cases involving partial conviction and acquittal. In the preceding financial year 2021-22, the Commission appealed in 57 cases. The increasing number of appeals also indicates a notable level of failure.

Let’s consider an example. In the financial year 2022-23, the special court has rendered judgments in 341 cases filed by the authority. Among them, the Commission has appealed in 237 cases involving partial conviction and acquittal. In the preceding financial year 2021-22, the Commission appealed in 57 cases. The increasing number of appeals also indicates a notable level of failure.

According to Transparency International’s 2022 report, Nepal is ranked 117th in terms of corruption. Out of 180 countries, our country received a score of 33 out of 100 points. Last year, Nepal also scored 33 points. A country with a score below 50 is considered to be a ‘highly corrupt country.’

Commission chief Rai attributes the increase in corruption to political instability. He states, “In the latest Transparency International report, although corruption seems to have slightly decreased, it hasn’t actually gone down. Corruption measurements fluctuate based on indicators, influenced by government activities. Corruption tends to rise during government changes.”

Chief Commissioner Rai notes that decisions beyond the purview of the Council of Ministers are being made. Even decisions made by provincial governments and rural municipalities are categorized as policy.

Former judge KC contends that corruption is shielded by the state under the guise of policy decisions. He remarks, “Even if policy decisions are not visible, bribery should be scrutinized! The Authority Act was poorly amended. The authority should be empowered to review policy decisions through legislative amendments.”