Why has Kathmandu’s garbage issue not been resolved? A look at the politics of trash and the billions of dollars that are made off of it.

BP Anamol | CIJ, Nepal

Balen Shah, the mayor of Kathmandu Metropolitan City, has recently become embroiled in a number of disputes. Few people are willing to accept the controversies he has been involved in as normal. Although he has a five-year term, why does he seem to want to stir up controversy right away? Perhaps only Balen has an answer to this. But he has developed a propensity to make comments on social media, seemingly without seeking anyone’s advice and disregarding the propriety of his position. He prefers to keep the media at a distance from himself.

All of Balen’s contentious deeds have one common cause: Kathmandu’s trash management issues.

Balen found it impossible to “remain at peace” for even a week after being elected mayor. He could do little else than think of how to manage the mountains of trash that towered in Kathmandu’s chowks and gallis. He commuted back and forth between Bancharedanda and Kathmandu on a regular basis.

A truck collecting Garbage in Bista village, Kageshwari Manhara-7. Photos: Manish Paudel

Bancharedanda residents, who live close to the Nuwakot-Dhading border, were enraged. The removal of garbage from Kathmandu was restricted there. Balen attended lengthy conversations with stakeholders back in Kathmandu between numerous visits to the site in an effort to appease protesters. Meanwhile, he was under so much pressure from the public and the media that it appeared as though he was powerless to take any other action until the garbage issue was resolved. Balen committed himself to finding a solution for nearly 1.5 months before giving up entirely.

“The politics in waste appeared to be so dreadful that if he had attempted to solve it further, his whole career would be beleaguered. Everyone was on the same page in hindering waste management,” one of Balen’s advisors said. “Once he realized that if he didn’t pull out of it, he’d get into difficulty, he promised to blacktop the road to Bancharedanda, and for the time being, eased waste disposal. But there’s no long-term plan. We can’t really say what will happen next.”

After abandoning the trash management campaign because it was too difficult to implement, Balen began tearing down squat buildings erected inside the city. Both proponents and opponents of the “dozer horror” were present at the time. Drives to ‘discover’ the old Tukucha stream through tunnel excavation and the demolition of subterranean buildings to make way for parking lots were increased. Balen doesn’t seem to be in the mood to disappear into the shadows, whether it is by using a bulldozer to raid a squatter camp or by intimidating street vendors in the sake of clearing the footpath.

Why did a mayor as aggressive as this one decide to withdraw from sustainably managing waste, Kathmandu’s perennial problem? And why was he keen on activities that could be termed ‘mayor terrorism’? “The kind of setback he received in waste management seems to have hurt his ego,” a Kathmandu Metropolitan City official said. “Now the mayor is like a wounded lion on the prowl.”

The politics of waste

The garbage emerging out of each of Kathmandu Valley’s homes, shops, and hotels is dumped at Sisdole and Bancharedanda landfill sites of late. The inside story of this seemingly unending waste problem is connected to politics and an income of Rs2 billion.

Let’s take an instance. In June last year, while Balen was looking for sustainable solutions to the problem, the local committees of Nepali Congress, CPN (Maoist Centre), and CPN (Unified Socialist) in Dhading’s Dhunibesi-1 announced that they’d put a permanent ban on waste disposal at the aforementioned landfill sites. Sending a joint letter to their respective party’s higher committees, they mentioned that garbage from Kathmandu Valley had made the lives of the locals there hard and unpleasant.

When these committees took such a decision, their parties were governing in the Bagmati Province and the center. At the central level, the parties kept mum about the warnings of the local committees. After sensing that the major parties themselves would pose hurdles to waste management, Balen had taken to social media to write, “The constitution envisions mutual cooperation and coordination between different tiers of government. But against this spirit, why do governments at different levels not help each other and play games to render them unsuccessful?”

Balen, who was elected as an independent, is alone in Kathmandu metropolis. Some argue that Balen’s ostracisation even among other elected people’s representatives and officials is not unnatural. But the ground reality tells another story.

When the CPN-UML won the position of Kathmandu mayor in 2017, the party was strong at ward level as well. The party led both the federal government and Bagmati provincial government. After it merged with the Maoist Centre to form NCP, it held a monopoly of sorts over the federal government, Bagmati government and Kathmandu metropolis. But even then, nothing was really done towards solving Kathmandu’s waste management problem.

What might be the reason behind this?

Though it is hard to exactly answer this question, when one chronicles the events, politics features prominently. Several instances point to the parties’ and their cadres’ ‘politics’ over waste.

One instance—in the November 20 elections, as many as 30 lawmakers were elected in Kathmandu district, including 10 in the House of Representatives and 20 in the provincial assembly. In the Kathmandu Valley, including Bhaktapur and Lalitpur, as many as 45 lawmakers were elected (15 in the HoR and 30 in provincial assembly). This number only accounts for those elected directly. What is surprising is that nobody has spoken a word about Kathmandu’s waste even after months since they were elected. It appears, it’s a non-issue for them.

So much so that even before he took oath of office, Member of Parliament Prakashman Singh, who was elected from Kathmandu-1, visited Melamchi river mouth leading a team and also met with the prime minister with his delegation. What could an MP do to bring Melamchi’s water to Kathmandu, a task that remains delayed even as all governments in the past several decades have worked towards it? If he could, then Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba would have already supplied the water and claimed responsibility for the success. But Kathmandu’s MPs can play a role in waste management. The issue, however, doesn’t seem to make their priority list.

Waste management featured prominently in Balen’s election agenda but Kathmandu’s parliament and assembly candidate didn’t even speak a word about it in their election campaigns. While Balen is taking the blame for botched waste management efforts, the newly elected people’s representatives are least bothered about it.

Some argue, why should MPs speak about the duties of local government? But in truth, it is in this very argument that Kathmandu’s ‘waste politics’ is connected to. Party leaders and cadres who have benefited from this kind of politics stay away from the whole issue. If someone comes forward with an attempt at a solution, they pose hindrances. Balen was on the receiving end of this maneuvering.

Because the landfill sites are outside the Valley, the ball is not on the court of Kathmandu metropolis or other local units here. Regarding this, the role of the federal and provincial governments is also important. But parties who are dominant in federal, provincial and local governments do not make any effort towards a solution. Instead, they instigate local residents at landfill sites and pose hindrances. Balen pulled out of the waste management drive because he couldn’t overcome those hindrances.

Why is Kathmandu’s waste problem not resolved? Who poses the obstacles? We put forward this question to Ram Kumari Jhankri, who was the Minister for Urban Development when Balen was elected and was also active in seeking solutions. Jhankri said that even though parties are not conspiring against a solution from the central level, their leaders and cadres at the grassroots are.

“Yes, those party leaders at the grassroots level are politicking over it on the back of higher-ups,” she said. “But we can’t exactly say who the conspirators are. We haven’t launched enough investigation into who really is responsible.”

Dumping site, Teku.

Waste from all of Kathmandu and even from Banepa Municipality reached Sisdole and Bancharedanda. The Valley had no waste problem until 25 years ago but with an increase in population and expansion in commerce, and hotel and restaurant business, it emerged as a major headache.

In the beginning, the Valley’s waste was dumped at Gokarna. After the landfill site there got full, the authorities started to dump garbage at Okharpauwa/ Sisdole on 5 June 2005 marking World Environment Day. Even though it was claimed that the waste would be dumped there for only three years, after 18 years, the authorities failed to come up with any other option. A total of 1200 metric tons of waste reaches Sisdole daily. After the Sisdole site got full, with a mountain made of waste, garbage began to be disposed of at Bancharedanda, which lies about 8km away at the Nuwakot-Dhading border.

Locals of Sisdole and Bancharedanda frequently stage protests saying the waste there has made them sick of lasting diseases. When they protest, the waste is not collected in the Valley and is seen strewn about in kitchens and streets. But it is not that the demands of the locals at the landfill sites are impossible to meet. They demand that the roads where waste containers ply be regularly repaired, and that the affected people be provided subsidized health care and education.

Though it is difficult for Kathmandu metropolis alone to fulfill these demands, if the federal and provincial governments want it, they can be met. But why was no step taken towards that? Why don’t members of parliament and assemblies make an effort towards that?

No mechanism or management

Even though the two metropolises and a few local units in Kathmandu Valley partially collect waste, most local units don’t do so themselves. Neither do they manage it. It is the private companies that have been doing that for years. What’s surprising is that the government doesn’t have a protocol for this. The companies have a free hand.

This ‘trade’ of waste appears to be the main obstacle to its management. Experts say that a large group is active in not letting the waste management succeed lest its income of years be gone; it is a group that has an access to political parties, their leaders and the government.

Separating the biodegradable and non-biodegradable waste in Dhobikhola corridor.

Nabin Manandhar, who is spokesperson for KMC and also the chief of its ward 17, says that there is a ‘big syndicate and politics’ in waste management. He explained, “A company takes responsibility to manage waste but it outsources the job to another company. Neither do the two companies have a written agreement nor does the government keep a record. If a company is collecting waste from a certain place, no other company can enter the jurisdiction. Where would these companies get all the courage to do so?”

Jhankri, too, cites the trade of waste as an obstacle to its management. “First off, the state is not clear about waste management, and then there’s the issue of income the individuals and companies make in the name of waste management,” she said. “The state could actually benefit financially from waste management but it didn’t get into that and handed over the responsibility to private businesses. When there’s no protocol, it’s all about connections. And then money is involved in that. Would those who benefitted from it let waste be managed sustainably?”

Jhankri adds that there’s additional and invisible income from waste and that has led to gangsterism.

Bhusan Tuladhar, an environmental expert, says that while the trade of waste is an obstacle to waste management, it is not the only reason. “The major reason is that waste is not in the state’s priority—there’s no change in how we look at waste and there’s no clear methodology on how to manage waste and whose responsibility it is,” Tuladhar said. “The main thing is about how to mobilize the private sector. Their motive is to earn money, and it’s a shortcoming on the state’s part that it can’t manage waste.”

Tuladhar sees similarities in how services like public transport, education, health care and waste management are operated—they’re all turned into lucrative businesses.

Dhundiraj Pathak, another expert on waste management, echoes Tuladhar, saying even though the private businesses are partly responsible for the long-standing waste management problem, it is the state that shoulders the most responsibility. “The citizens are paying tax and the government is also spending money. Where does all this money go?” he said. “When private companies levy fees, it’s their responsibility to not only collect the waste but also to manage it. When waste is managed sustainably, the companies currently engaged in waste collection would be bound to think about their role—that’s another aspect. But is it okay for the metropolitan city to remain inactive just because of that?”

Dominance of the private companies

Companies that collect waste levy fees to each household, shops and businesses in the Valley. But there’s no legal basis to that. They fix their own rate. They do so just on the basis that they are registered in the company registrar’s office and local units.

For instance, the company ‘Baneshwar Mahila Batabaran Sewa Pvt Ltd’ collects waste from Kathmandu metropolis’s ward 10, 31 and 32. The company started work in 2059BS under the name ‘Mahila Batabaran Sanstha’ and was registered at the company registrar’s office in 2068BS. The company collects waste from altogether 3232 members, including households and businesses. It’s operator Durga Dulal says that the company charges a minimum of Rs450 to Rs10,000 from each of its members monthly.

“We charge depending on the quantity of waste we collect from households, between Rs450-Rs500. For hoteliers, we charge between Rs5000 and Rs7000, and for party palaces and banquets, we charge Rs10,000,” she said.

Another company, ‘Paribartan Sewa Samiti’, which is based in Kathmandu-17, has been collecting waste since 2062BS. The company started collecting waste from Kathmandu-7 and is today the one that collects the most quantity of the Valley’s waste. The company’s operator, Mitra Prasad Ghimire, who is also the general secretary of Waste Management Association, says that his company collected waste from Kathmandu’s wards 6, 7, 8, 15, 17 and 18, and also from the Parliament office, Pashupati Area Development Trust, residences of ministers, assorted ‘VVIPs’ and Banepa’s southern area. The company categorizes waste and also recycles it into compost manure.

Ghimire says that his company collected waste from 30,000 households. “We charge Rs50 for a single shutter shop, and above that, depending on the quantity of waste collected,” he said. “The Kathmandu Mall alone pays Rs42,000 monthly.”

None of these companies are in a binding contract with the government, which doesn’t have the record of how much money these companies make.

Ishwarman Dangol, chair of Kathmandu-15, said that private companies are charging fees as they please. “They don’t seem to be paying tax, that’s why they are an illegal enterprise. Stakeholder agencies should control it,” Dangol said. “The metropolis has been unable to move ahead with a plan. There’s politics of give-and-take involved in waste. But everyone’s turning a deaf ear.”

Even though waste collection and management is the duty of local units, they are turning away from it, the reason private companies are holding sway, Dangol said.

Ghimire, the general secretary of Waste Management Association, says that waste is being collected without any agreement with any agencies. He adds that even though government agencies know of it, they are keeping mum because they are unable to fulfill their responsibilities. “The government hasn’t come forward to sign an agreement, and how could it monitor it?” Ghimire said. “They don’t manage waste themselves. It’s like we are doing it for them. Work takes money, that’s why we charge fees.”

Dulal says that even though they have repeatedly advised the metropolis to sign an agreement, it hasn’t paid heed.

According to Sarita Rai, chief of the metropolis’s environment department, says that the metropolis itself collects waste from main roads, public spots and wards 12, 18, 1, 20, 21, 23, 24 and 25. The metropolis also partially collects waste from wards 5, 6, 7, 11, 13, 15, 16, 17, 22, 26, 27, 28 and 32, she says.

According to Rai, as many as 72 vehicles collect waste from these areas and take it to Teku Transfer Station. She added that containers ferry waste from hospitals, schools, banks, plazas and public offices to the transfer station, from where tippers and containers of 8 and 13 ton capacities transport it to Bancharedanda for disposal. On average, 135 vehicles reach Bancharedanda daily with Kathmandu’s waste.

Income from waste exceeds Rs2billion yearly

Of the 77 companies under the Waste Management Association Nepal, 66 collect waste in Kathmandu Valley. Of the Valley’s 22 local units, waste from 18 are collected by these companies, while Kathmandu Metropolitan City, Lalitpur Metropolitan City and Bhaktapur and Madhyapur Thimi municipalities collect their waste partially in coordination with private companies.

Of the 1200 metric tons of waste in the Valley, Kathmandu metropolis alone produces about 600 tons. Of the 66 companies, 38 operate at the KMC.

While investigating into the operators of these companies, we found that some had from to 25 joint owners. According to the Association, as many as 400 individuals hold the ownership of these 78 companies.

What is interesting is that an office holder at the Association said that most of the companies’ owners were affiliated to one or the other political party. It is because of that political connection, nobody attempts to bring them to the state’s radar. And the local units too play accomplice to them, showing no interest in collecting waste.

The evidence is that none of the local units have forged any agreement with them. The local units only charge them for rented containers.

“An integrated waste management project formulated by 10 local units including KMC is currently in the process of coming into force after agreement with Nepal government investment board and NepWaste, and because there’s official agreement with any private companies, the metropolis hasn’t charge any company any money,” reads a document provided by Rai.

For vehicles of capacity up to 8 tons to dispose of waste at landfill sites, the metropolis charges Rs300 and for vehicles over that capacity, Rs400, as disposal fee. In the fiscal year 2078-79BS, the metropolis collected Rs1,17,76,700 as disposal fee.

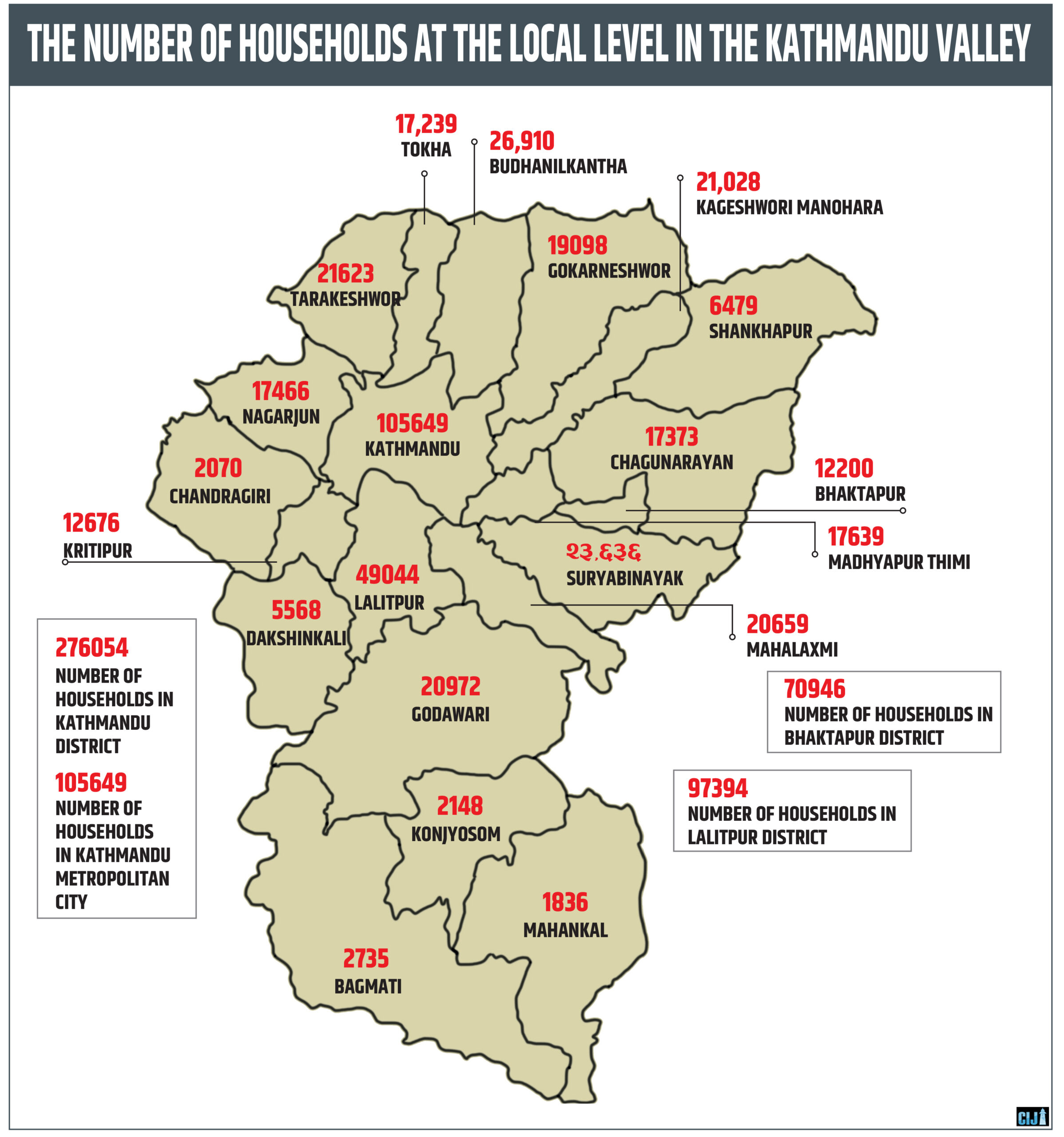

According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, there are as many as 4,44,394 households in Kathmandu Valley within its 21 local units. Waste from nearly 75 percent of them is collected by private companies.

According to the statistics of private companies registered under the Association until 2078BS, they have as many as 2,49,602 members in 18 local units in the Valley. By which, the companies collect Rs14,97,61,200 with Rs600 on average monthly from each member. That amounts to Rs1,79,71,34,400 yearly.

But the statistics provided only include households. The companies also charge businesses and shops. And there’s more money to make for them after the waste is segregated.

Dangol, the chair of Kathmandu-15, says that the companies, party cadres and other stakeholders expand their area of work in the name of tole sudhar committees and clubs. Many of these companies collect waste from bazaar areas and dispose of them haphazardly at Bagmati, Rudramati, and Bishnumati river corridors in the night. While they contribute to pollution, they are not booked.

But on what basis do these companies fix their fee rate? After formulating a directive on work operation monitoring and evaluation 2076BS, the companies came up with new rates from Chaitra 1 that year, citing an increase in price of petroleum products. Some companies even go against the directive and fix a rate of their own.

When local units were without people’s representatives in 2051BS

Before 2046BS, a German company collected Kathmandu’s waste for 10 years. After that, local units themselves began to collect it. In 2054BS, after representatives were elected to local units, they collected Kathmandu’s waste until 2059BS, according to Dangol.

Dangol was also the ward chair in 2054BS. “The metropolis had assigned an organization for door-to-door waste collected then,” he said. “After 2059BS, local units were without representatives, and the private companies entered in waste collection to fill the void.”

After waste management proved difficult, tole sudhar committees and other such groups began to collect waste, registering themselves at district administration offices, Dangol recalls. After then, the number of companies began to rise. “And gradually, they began to hold sway,” Dangol said.

It’s not that there has been no effort for sustainable waste management. After 2070BS, the government dubbed waste management a ‘pride project’ and decided to operate it under the investment board. After it was decided the board would assume responsibility of projects worth over Rs6billion and other entities projects under that, the board issued a tender and selected the company NepWaste. “There was already an agreement in the city working committee and council to assign NepWaste for the task,” Dangol said. “Other local units within the Valley had decided to assign the KMC to do an agreement. But then Mayor Bidya Sundar Shakya didn’t forge any agreement for reasons unknown. After that, the tenure of local representatives was over.”

The KMC can still sign a project development agreement (PDA) with NepWaste. For that, the government would have to provide 300 ropanis of land at Bancharedanda area for the private sector’s waste purification center. The investment board in 2076BS had given the responsibility to invite private investment on waste management to local units, except for Kirtipur and including KMC, Dakshinkali, Chandragiri, Nagarjun, Tarakeshwar, Tokha, Budhanilkantha, Gokarneshwar, Kageshwari Manohara and Shankharapur.

For a sustainable management of Kathmandu’s waste, a sanitary landfill site is currently being constructed at 31,000 sq ft area in Bancharedanda’s base by diverting the Kolfu river. According to the auditor general’s 59th annual report, the site would sustain mixed waste for 20 years and segregated waste for up to 40 years. With that aim, a leachate pond of 20,000 cubic meters and a sedimentation pond are under construction with scientific procedures, according to the report.

After Balen Shah pulled out of the waste management issue, can Bancharedanda landfill site alone keep Kathmandu’s suffocation at bay? How can the politics and business of waste be tamed?

Jhankri, the former urban development minister, also says that businesses with vested interests have posed hurdles to sustainable waste management fearing their income would dry out afterwards. “As waste collection is not codified, many people saw it as a source of income, and they stopped it from being legalized fearing their income source would dry out,” she said. “The state is negligent to such an extent that it hasn’t envisioned income out of waste on the streets. Instead, a few people are making money out of it.”

Jhankri concludes that the bureaucracy is also assisting this nexus. “Bureaucracy also benefits from administrative and legal hassles. If it is brought under law, officials fear losing their benefits,” she said. “Because many are benefitting from mismanagement, nobody is willing to give a chance to sustainable management efforts.”