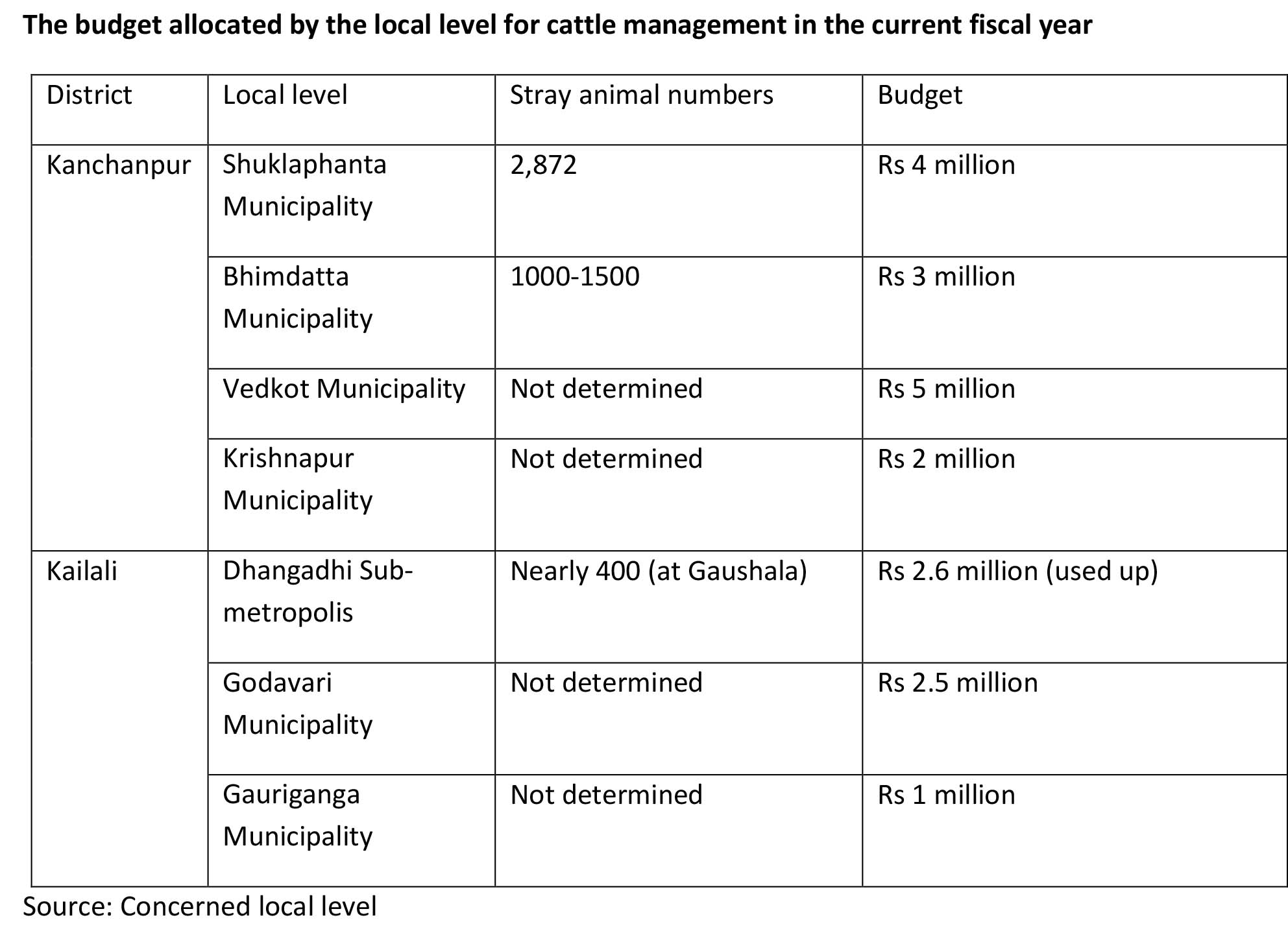

Local governments in Kailali and Khanchanpur spend Rs 20 million in total annually on stray cattle management as people abandon their old cows that don’t give milk and old oxen that can’t till land on the streets.

-Avinash Chaudhary : Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Two main cities of western Nepal are getting ugly these days. Stray cattle that roam around freely and their litter have ruined urban beauty. Local residents find it hard to move about freely and to secure their crops from the animals.

“Animals existed in plenty [in the past] but the city was beautiful,” said Hirasingh Patali, chairperson of Dhangadhi Sub-metropolis Ward 5. “People have started letting their cattle go astray.” He thinks that there are more animals on the roads in Dhangadhi now than in sheds. ‘Stray cattle’ have been a problem in Dhangadhi in the past two-three years.

During the local level elections held on June 28, 2017, management of stray animals was a major agenda. Local leaders of political parties, who stood for various posts of the sub-metropolis, had promised to control the movement of stray cattle.

The practice of people leaving their cattle astray after reaping benefits from them has led to a growth of animals on the streets. Oxen that cannot be used to till land anymore and cows that do not give milk anymore are led onto the streets discreetly.

Enraged locals parade stray cattle on the Dhangadhi Sub-metropolis premises after the animal inflicted damage to their crops. Photo: Avinash Chaudhary

Chief of Bedkot Municipality in Kanchanpur Ashok Chand said carelessness and defiance of local people had made it difficult to manage stray cattle. “Reaping benefit as long as it is available and abandoning the cattle when they are not of much use has created problems,” said Chand. “This problem would not be there if people managed their cattle on their own.”

No agency has data on the number of stray animals in Kailali and Kanchanpur. Deputy chief of Lamkichuha Municipality in Kailali Tika Thapa says the number is growing since there has been no end to the release of animals from farms. “We often send stray cattle to other districts,” said Thapa. But the animals are not under control as new ones continue to join the flocks, she added.

Most farmers in Kailali and Kanchanpur raise cows for milk. Some have cow farms. The farmers look after the cows as long as they give milk or until they are old. They release cows when they can be milked no more. “Farmers don’t keep cows that can’t be milked and oxen that can’t till,” said Shuklaphanta Municipality chief Dil Bahadur Air. “Cattle left to roam by farmers have grown uncontrollably.”

Pastures are shrinking since the concepts of community and protected forests came into force. There are no enough grounds for collecting fodder. Since the enforcement of Community Forest Act in 1993 and the subsequent Regulations, local residents cannot graze their cattle in community forests. Since the declaration seven years ago of the Basanti corridor in Kailali as a protected area, farmers’ space to collect fodder has shrunk. This has given local residents a perception that taming “useless” and “unyielding” cattle is merely a “waste of resources”.

A farmer in Godavari, Dede Lohar complained that stray animals eat up crops. “Flocks of cattle graze on crops. These days, I spend my days and nights on the field to guard crops,” Lohar said. According to him, a flock of 40/50 cattle destroy crops at Chaukidanda. Due to the stray cattle menace, farmers of Chaukadanda take turns to guard the crops they took troubles to grow against stray cattle.

Ramdasi Chaudhari, who does commercial vegetable farming in Dahangadhi Sub-metropolis-8, is tired of chasing away stray cattle. “It’s been hard to save vegetables from them. I drive the cattle away during the day but they roam about the vegetable farm at night and destroy it,” she said.

With the popularity of farm technology growing, bullocks are no longer used for tilling fields. Farmers are attracted to tractors, power tillers and mini tractors, making oxen and buffaloes redundant. Reaper, thresher and combine harvester are used these days to harvest paddy and wheat, for which oxen were employed in the past. As farm machines are available whenever necessary, there are no buyers for oxen. “There is no pasture to graze cattle. We can’t keep many cows and oxen,” said a farmer in Dhangadhi, confessing quietly that they leave those no more in use.

Stray animals tamed at Beli Gaushala in Dhangadhi. Photo courtesy: Prem Chaudhary

According to Shuklaphanta Municipality chief Dilbahadur Aire, drafting of law provisioning fine for those not taming their cattle had failed to confine animals to people’s households. “This is a common problem. All need to find a solution.”

Asked about the proliferation in cattle numbers in the city, Dhangadhi Ward 1 Chairman Santosh Mudvari said, “Stray cattle would be exported to India until a few years ago. The problem arises since there’s been a decline in the trend.” According to him, the cattle used to be taken across the border to feed the beef industry. When Yogi Adityanath was elected chief minister of the neighbouring Indian state Uttar Pradesh, he put an end to cow slaughter there. As a result, cattle export almost ground to a halt, said Mudvari, explaining the reason for the cattle being widespread on the streets.

Stray cattle have also been the cause of road accidents. “Stray cattle come onto the streets out of nowhere. Speeding vehicles can’t be stopped immediately so accidents happen,” said Tek Bahadur Jora, information officer at the Far-western Regional Traffic Police, Attariya. It is worse when stray cattle come onto the streets when visibility is low, he added.

Jora said that the traffic police office, in coordination with the local level, has taken initiatives to control stray animals. The regional traffic office has 36 units under it. Each day, one or another will be organizing events on stray animal control and traffic management.

Executive Officer Mohan Prasad Marasini of Godavari Municipality in Kailali said the programme needs support of the local people. “This has to be controlled at the people’s level,” said Marasini. “The municipality can’t reach households to check who set free animals. Laws won’t be able to control it either.”

Krishnapur Municipality has set Rs 5,000 for people releasing domestic animals per instance. But it is hard to trace who an animal belongs to since cattle are released at night, said Karna Hamal, the municipal chief. “We also have provisioned half the fine collected from the cattle owner for the person informing about the guilty,” said Hamal. “Even this was not effective.”

As the stray cattle problem is growing into a menace, some local governments are trying to confine them by building Gaushalas. Godavari Municipality has spent Rs 2.5 million so far this fiscal year to tame the animals. Executive Officer Marasini said the problem remains as grave as ever despite spending on the sheds and cow taming.

As the stray cattle problem is growing into a menace, some local governments are trying to confine them by building Gaushalas. Godavari Municipality has spent Rs 2.5 million so far this fiscal year to tame the animals. Executive Officer Marasini said the problem remains as grave as ever despite spending on the sheds and cow taming.

Municipalities have been using their resources to build Gaushalas and sheds for the animals, buy fodder for them and to pay cattle herders. Ward Chairman Santosh Mudvari, who is also the Dhangadhi Sub-metropolis spokesperson, calls this expenditure “non-essential”. “The defiance of locals has got us to make this unproductive payment. This money could be used in development works,” he said.

Krishnanagar Municipality chief Hamal has similar experience as Hamal’s. “For stray cattle management, I set aside Rs 2 million from capital budget for Gaushala construction and fodder purchase, etc,” says Hamal. “But local residents pulled down the Gaushala.” Since cows and oxen tamed at the Gaushala often strayed out and damaged crops on the fields nearby, local people stood against building the structures near their fields, he said, adding that they would destroy the structures at night.

The stray cattle problem is acute particularly in six local federal units in Kailali and five in Kanchanpur. No agency has exact data on the number of stray animals in the two districts even as the cattle are seen everywhere in public places such as highways, rest houses and religious sites. Local governments are trying to maintain their records by setting up Gaushalas. According to statistics from the Regional Veterinary Directorate, 184,666 buffalos and 360,248 cows exist at farmers’ households in Kailali and Kanchanpur districts.