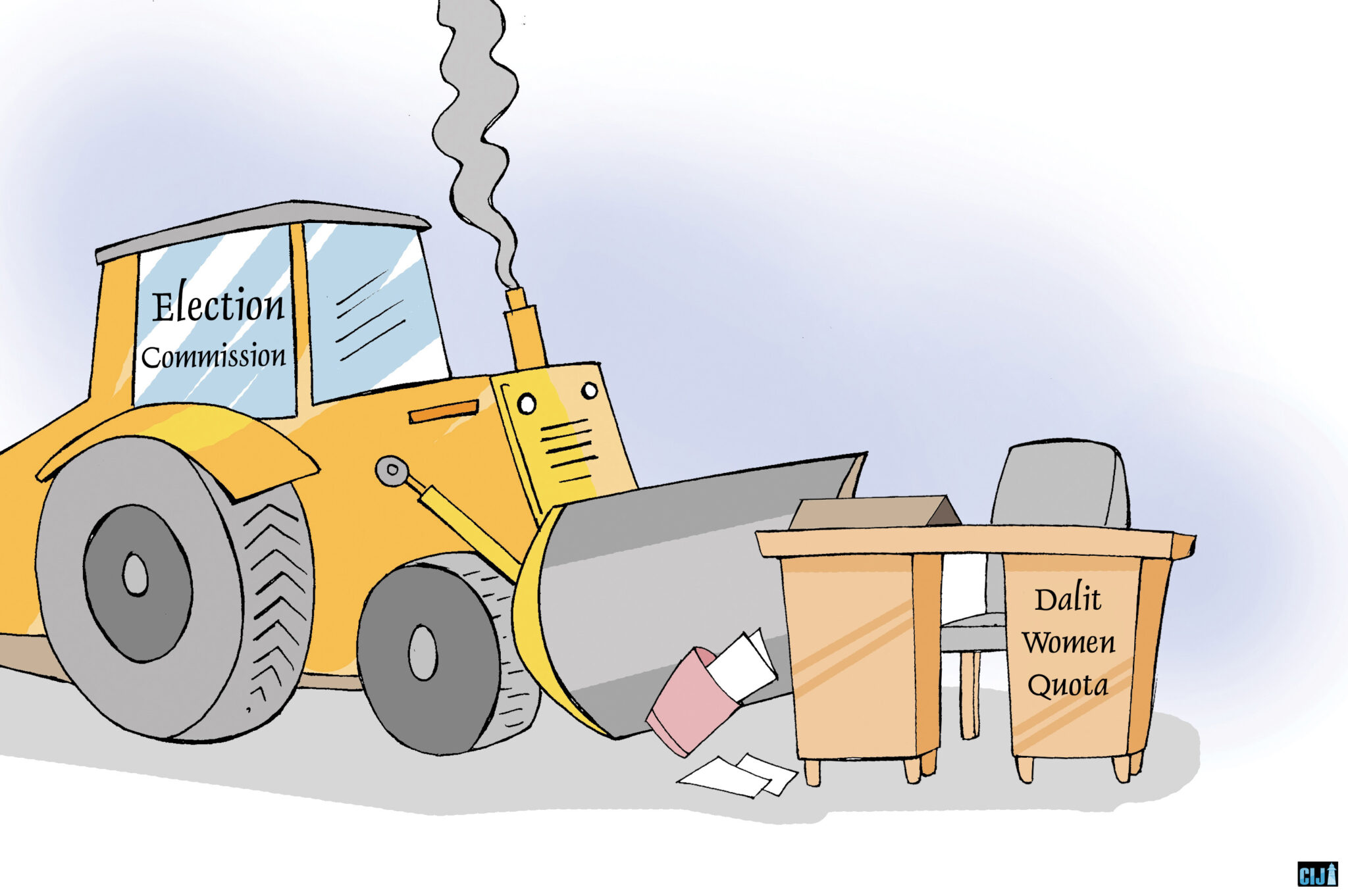

Nepal’s apex court has questioned and stopped the employee integration decision made based on federal law. As a result, local and provincial administrations, supposed to be stable and well-functioning, have been severely affected.

Krishna Gyawali, Center for Investigative Journalism, Nepal

On 10 September 2021, Sarita Sharma (who wanted to be identified with a pseudonym), a seventh-level officer at a local unit in Kathmandu valley, took a leave from her office and, within an hour, submitted her documents, including an appeal, to a ministry inside Singhadurbar.

She was happy as her switch was ensured. “I am happier now than when I passed the public service exams,” she said. “We competed for federal service but were transferred to local units, an injustice to us. I feel I have only now gotten the deserved responsibility after the court’s order.”

Officials like Sarita who have fought cases against the Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and have now returned to service at federal level as per the court’s interim order are not willing to reveal their identities to the media. According to Basanta Adhikari, spokesperson at the Ministry, nearly 200 such officials have returned to work at federal level after the apex court’s interim order. Many other cases are under deliberation at the court.

The constitution promulgated in 2015 envisions the division of the state under three levels—federal, local, and provincial. Since there was only a federal set-up earlier, the bureaucracy was likewise only federal in structure. Now, since most of the offices are governed under the provincial and local levels, they require additional officials.

Alongside, the remit and positions of the employees were heavily axed at the federal level. According to Adhikari, of the total 79000 public service employees, only 48000 remained at the federal level under the new setup. To balance the numbers of human resources, a provision was added where employees at the federal level would be integrated to provincial and local levels.

A coercive approach

According to the constitution, the Employee Integration Act was enforced in 2017. The act envisioned the employees would be given the opportunity to choose their offices under seniority basis, and the additional employees would be deployed at local and provincial levels.

The act also had a provision to allow the employees to return to federal service after a certain duration. But some time after KP Oli became prime minister, the Employee Integration Ordinance-2075 was issued, effectively canceling the act itself. According to which, a new act was promulgated.

The employees integrated according to the new law would now have to work at provincial and local levels forever. For that, they would receive up to ‘two grade’ encouragement salary (amounting to two days’ salary) added to their basic salary. They wouldn’t get a chance to return to federal service unless they get promoted.

Since the federal Public Service Act couldn’t come into effect, it was not clear whether they could take part in open competition for federal service. This concept of employee integration, put forward with a coercive rather than encouraging approach, led to widespread dissatisfaction among employees.

“The existing employees competed under the federal setup. We emphasized that if they were deployed in provincial or local levels, they would get a chance to return to federal level. We suggested that rather than complicating the integration process the employees be deployed only to get work done,” says Umesh Mainali, the former chair of Public Service Commission who retired recently, “The initial act had the provision that the employees could return to federal level after some time and they couldn’t be punished without consulting the commission. I think that if the integration was carried out under that act, it wouldn’t encounter the problems it has now.”

The employees appointed between 2073 and 2075BS just before the integration was enforced bore the brunt. Because they were at the tail end of seniority and the chance to choose the levels was provided under the seniority basis. Those who had competed for federal positions were integrated at the local levels. And those who competed for federal position after their lot would have their postings at the federal level itself after the integration was complete.

“The senior employees would remain at the federal level and also the latter lot,” says Adhikari, the ministry spokesperson. “Why do those who were appointed in between have to work at local levels?—their concern is valid to an extent.”

Selfish interests galore

According to a writ petition filed by 34 section officers at the Supreme Court, the Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development deployed employees to local levels during integration while keeping its positions secretive. Shortly afterwards, it opened an advertisement for section officers on 560 positions.

The officers allege that they were deployed to local levels coercively by hiding the positions. The ministry hasn’t denied the charges. Spokesperson Adhikari says that since the ministry was focused on integration, there “might have been some mismatch” on the number of vacant positions.

The employees further allege that the ministry deployed the section officers to local levels to promote deputy principal executive officers (Nayab Subba). When the positions of section officers are vacant, 40 percent of it is filled through internal competition and the rest through open competition. The section officers allege that when the number of vacant positions is large, it would lead to quick promotion of deputy principal executive officers, so the section officers were integrated to local units while keeping the positions vacant.

But Mainali, the former chair of the public service commission, says that this attitude is wrong. “There was discrimination between those who were in the service and those competing from outside. I am of the opinion that the provision that those in service were allowed for internal promotion and open competition is a little skewed,” Mainali says. “That’s why, the opinions like those in parliamentary committee service couldn’t compete and if they did, then their old tenure would not be added, must have been floated.”

Employees whose exams were halted because of the court order also raise questions on the role of Chief of Public Service Commission Madhav Regmi. But Regmi says that since the apex court itself has ordered, there was no option than to postpone the exams. “When we completed the interview round and were preparing for result publication, three employees were infected with coronavirus, and one had to perform 13-day death rites,” Regmi said. “The interim order was issued when we were waiting for them, leading to the postponement.”

The employees wanted change but didn’t accept it when the change was granted to them, and they became anarchic.

The perennial draw of the center

Mostly, public service employees want to be in Singhadurbar and around the federal center. Since being away from the capital and in the rural areas robs them of facilities, they want to work in a well-facilitated place. According to spokesperson Adhikari, of the 9400 employees elected to local level, nearly 3000 have submitted appeals for shift in postings. He says, “Of them, about 2000 just want to come to Kathmandu.”

For public service employees, a well-facilitated place like Kathmandu is a major draw as they keep in mind amenities for themselves and their families, and opportunities of education and healthcare. Local unit offices outside the capital are located in small bazaars. Employees don’t want to get posted to those areas for a lack of personal development and other opportunities.

According to former minister of general administration Rekha Sharma, even though the country has adopted a federal structure, public service employees still want to come to the center. “There may have been a change in structure of the state but the employees’ mindset has not. Province and local levels are still a second option for them,” she says, “This requires it to be addressed legally. Otherwise, no one will be willing to move to local units in rural areas for work.”

Employees blame the government policy as the reason behind their attraction to federal service even after the recent integration drive. While the government has said those integrated to local units would be promoted, they were only upgraded, they allege. According to the grade system, that means merely a raise of two days’ salary for them. Employees of section officer level won’t consider it a promotion when they only get a position of ‘sixth-grade’ officer.

Those who pass the exams under federal service can work around the country. But with the integration, they would be limited to a certain local unit or province. Employees have to take consent of four personnel, including both chiefs in the office they are leaving and going to. According to an employee who recently passed the exams, “When you are a section officer, you can be the chief of many offices. But there’s no such opportunity at the local level.”

The Federal Public Service Act is yet to be enforced. Because of which, there’s no clarity whether employees at local and provincial levels can compete for federal level, or whether they can partake in internal competitions. Owing to which, employees are not drawn to the integration in local units.

Menaka Kafle, deputy chair of National Federation of Rural Municipality, an umbrella association of rural municipalities in the country, and chair of Jhapa’s Kamal Rural Municipality, says that it’s because of these reasons that there’s high turnover of employees at local levels.

“Even though they work at local levels for some time, federal employees eventually want to move to federal level. And they just don’t want to work in rural areas,” she says. “Maybe it is human nature to want to stay in well-facilitated places. Either there should be a policy to encourage employees to work at local levels. Or there needs to be an immediate transfer of employees from the provincial to local levels.”

The court order and the travails afterwards

On August 9, 2021, the Supreme Court ordered to repeal the integration of 34 section officers, and returned them to federal public service. The case, filed on December 25 2022 by the officers saying that they were unlawfully integrated, was heard after eight months.

Not only that, the apex court further ordered that the employees be integrated into the federal level and the vacant seats be filled only after subtracting the number of employees who filed the case. Another order said the old employees shouldn’t be substituted by the new ones. After that, many other employees filed their cases and got orders.

The court kept on issuing interim orders. According to Regmi, once the integration of 34 section officers was repealed, the cases began to increase at the court. “Now the orders are coming ordaining that even low level public service employees not be integrated.”

Because of the court order, nearly 500 positions now remain vacant. The section 28 of Public Service Commission Act states that the public service commission’s employment process can be canceled but for that, the government should issue letters mentioning reasons.

“At least, the court order against the act should be stopped. Since the commission was not directly linked to this process, the court shouldn’t ordered it to do this or that,” Mainali says. “The commission could deny any other body’s order but not that of the court.”

According to Mainali, “The commission should have gone to the court asking the order be canceled.”

The court repealed the integration on the basis of the officers’ claim that they were unfairly treated since government had hidden the number of vacant positions and filled them after integration. The August 9 order of justices Tej Bahadur KC and Kumar Chudal and later the 20 August order of Chudal’s single bench are much alike. Even though details on how the positions were hidden and how was not mentioned in the writ petition, both the orders have pushed forward the elementary view that the positions were indeed hidden as per a letter of Department of

Civil Personnel Records.

With the government request following integration, it has opened vacancy for 560 personnel for the first year and 114 for the next year, which is very high than usual. In a written response about the integration case, Ek Narayan Aryal, secretary of Local Administration Ministry, has said that there was some mismatch about vacancy number following integration as the vacancy was reviewed in many government agencies. It appears that the court based its order on those details.

Lalbabu Pandit, the former minister who claims that the employee integration is constitutional and lawful, accuses the minister succeeding him, Hridayesh Tripathi, and other officials of doing wrong work and repealing his decision in cahoots with the court.

“Employees deployed to local levels moved the court asking for their rights in vacancies in the federal level, and the court understood the integration as shifting of the employees,” says Pandit, who was Minister of Federal Affairs and Local Development at the time of the integration. “The employees wanted change but didn’t accept it when the change was granted to them, and they became anarchic. An employee won the case and based on that precedent, a series of wrong work ensued.”

The court, which just repealed the integration at first, later ordered the process to fill vacancies of public service commission be stopped. Mainali, the ex-chair of the commission, says that once the examinations start, the examinees’ rights would take over, so the appointment process cannot be stopped.

After a flurry of court orders, the local units are reeling under a shortage of human resources. Once the integrated personnel returned to federal level, either the local level has to appoint temporary employees or wait for at least a year for the provincial public service commission to fill the vacancies.

Kafle, the chair of rural municipalities’ federation, says that after the integration was repealed, it is getting difficult to get works done for a lack of employees. “It is hard to carry out even the regular works, let alone additional ones. Local units were already short on employees. Now those who were there have returned to federal level,” says Kafle. “Employees in technical offices working under the municipality have to be deployed towards. The cutback has spelled further troubles.”