The government is bent on purchasing equipment rather than managing human resources for critical care units.

Sagar Budhathoki | CIJ, Nepal

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, many patients lost their lives due to a lack of human resources in critical care facilities across Nepal’s hospitals. But the government is still focused on amassing equipment. It is imperative that a responsible government should focus on human resource management by engaging local units to ease the operation of critical care services.

Because of a lack of human resources in critical care services across the country’s hospitals, many patients had to lose their lives. Physicians working at critical care units say that the government tendency to purchase equipment for commission while ignoring human resource management is to blame.

Health professionals at TU Teaching Hospital care for patients in the Intensive Care Unit. Photos: Bijay Gajmer/ CIJ, Nepal

Physicians claim that over half of those who died during the pandemic could have been saved if there were proper critical care service. And there are many incidents that prove that claim.

For instance, on April 23, 2021, a 48-year-old man from Bajhang’s Jayaprithvi Municipality was admitted to the district hospital. The hospital did have ICU and ventilator services, but no person to man them. The man, who was kept at the hospital for three days, died on the way to Kohalpur where he was being taken for further care.

In another instance, another Covid patient succumbed to the disease on May 8, 2021, in Mahottari’s Jaleshwore Hospital because of a lack of manpower to run its ventilator service. The 43-year-old patient died while he was being taken to Janakpur for further treatment.

Another 42-year-old patient from Myagdi’s Beni Municipality-5 died because of similar reasons. He was admitted at Beni Hospital on 11 May, and died a day later, after he required ICU care, which the hospital couldn’t provide for a lack of human resource.

In Bharatpur’s Chitwan Medical College, one patient died on September 22 while undergoing a kidney transplant. Alleging that the patient died because of physicians’ negligence, the relatives of the deceased filed a complaint at Chitwan District Administration Office and Nepal Medical Council, Human Organ Transplant Coordination Committee.

According to Human Organ Transplant Methodology, two anesthesiologists are required for the transplant process, but, the complaint alleges, the patient’s process had not a single one.

These four incidents illustrate the dire lack of human resources in the country’s critical care units.

According to data from the Ministry of Health and Population, by September 2020, Nepal had a total of 524 ICU beds and 222 ventilators. A year later, that number increased to 2944 and 1036, respectively. But the government paid no attention to adding human resources to operate them.

A recent Public Service Commission advertisement illustrates how critical care in Nepal’s public health sector is in total neglect. While the commission issued vacancies for a total of 94 professionals, including medical officers, nurses, pharmacists, and lab technicians, not a single vacancy called for critical care professionals.

The Ministry of Health and Population’s recently-released national policy for health professionals presents an estimate of human resources required and being equipped for the health sector between 2020 and 2030. But the policy has no mention of manpower estimates for critical care.

Currently, physicians from other specializations (such as anesthesiologists, general physicians, and surgeons) are taking care of patients in ICU by taking time from their duties. Because of this, patients at the ICUs haven’t been able to get optimal treatment and service.

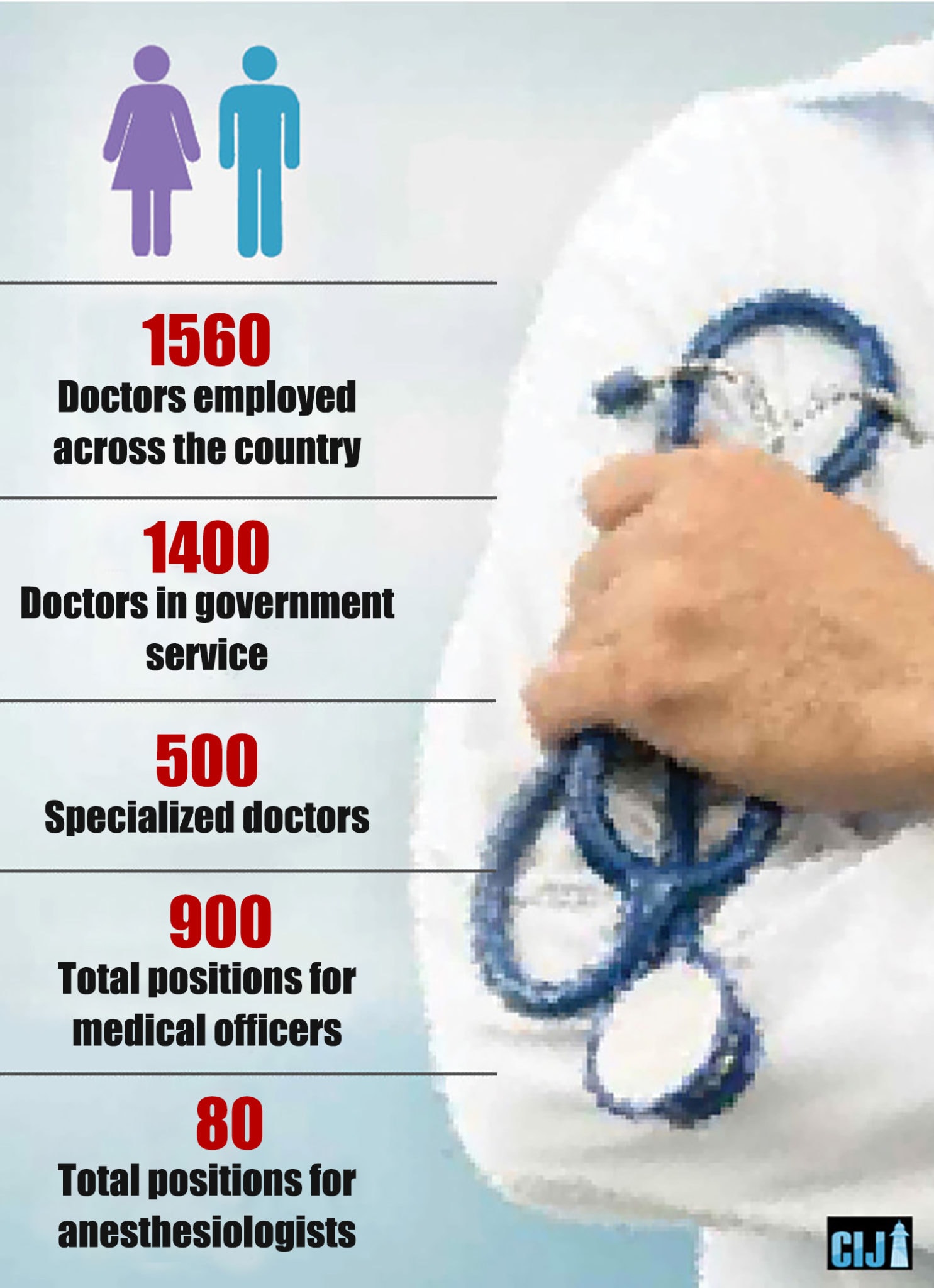

Of the 1650 physicians across the country, 1400 are from government service. Of which, 500 are specialist physicians and 900 from medical officer vacancies. There are only 80 anesthesiologists under the government vacancy.

According to ministry data, of anesthesiologists, only seven are super-specialists. Of them, three are employed at Bir Hospital, two in Pokhara Health and Science Academy, and one each in Paropakar Hospital, Thapathali, and Birgunj’s Narayani sub-zonal hospital.

In other countries, the practice has it that the ICU is led by either intensivists (those who have an MD in anesthesiology) or those who have a special training in critical care medicine for one to three years. But in Nepal, there’s no post of intensivist allocated in the entire health service.

Dr. Krishna Poudel, director at the Department of Epidemiology and Disease Control, concedes that patients have been bearing the brunt of a crushing lack of manpower in critical care. He says that Nepal’s critical care service requires three times the manpower it currently has.

A pathetic situation

In Myagdi’s Beni Hospital, the proper functioning of its five-bed ICU requires at least three doctors and 12 staff nurses but it has none at the moment. Dr. Jitendra Khanal, the hospital’s medical superintendent, says that the hospital is run by one permanent MDGP (MD in general practice) and four medical officers working on a contract basis. “The officers under contract basis are leaving soon on study vacation,” says Dr. Khanal. “It is impossible to run the ICU in the current situation.”

Dolakha’s Charikot Primary Health Centre has five ventilators, two PCICU (ICU for kids), and a six-bed HDU. The hospital, which has 50 beds, has ICUs and ventilators sent in by the provincial government but no manpower to operate them, according to Dr. Binod Dangal, the hospital’s medical superintendent.

The Danda-based district hospital of East Nawalparasi has six health workers, five-bed ICU, and three ventilators, but because of a lack of specialist physicians, three of its ICUs remain unused, according to Chhabilal Subedi, information officer at the hospital.

Meanwhile, in Manang District Hospital, two ventilators are stored unused. While the Karnali Province has ICU beds and ventilators in 10 districts, only those in Surkhet and Jumla are in operation.

According to Rabin Khadka, chief of Karnali Province health service directorate, the province has a total of 35 ventilators, 64 ICUs and 50-bed HDU. But except for four in Surkeht and two in Jumla, others remain unused, for a lack of manpower.

“While the patients were desperate during the pandemic, we couldn’t treat them in ventilators and ICUs,” says Dr. Khadka. “The situation is such that six anesthesiologists are covering 10 districts.”

Madesh Pradesh faces a similar situation. According to Bijaya Jha, director of provincial health directorate, the province has 69 ventilators but no one to operate them.

Anesthesiologist Paras Pandey of Bheri Hospital says that patients “who could have survived” have died for a lack of manpower. The problem is a “chronic” one in the country’s health sector and has cost dearly during the pandemic.

“Critical care always lacked manpower,” says Dr. Pandey. “It cost us dearly during the pandemic. Many patients who could have been saved died. If the pandemic explodes again, the loss is bound to repeat.”

Between January 2020 and November 2021, a total of 11557 people died of Covid, according to government data. Physicians say that over half of those deaths occurred for a lack of critical care service. Let alone critical care, many patients died because of a lack of oxygen, the estimated data say.

Dangal, the medical superintendent of Charikot Hospital, says that because the government is bent on amassing equipment, critical care has been severely neglected. He sees three major reasons behind this: a greed for commissions, political interests and a lack of vision.

“Those in responsible positions are bent on amassing equipment for commission,” he says. “The equipment in the hospitals, however, have been shelved away, because leaders want to show that they have done the work rather than actually doing it and there’s a lack of vision among the authorities. Otherwise, why would anyone send a ventilator to a place where there’s no one to operate it?”

The NSCCM’s criteria

The criteria set by the Nepalese Society of Critical Care Medicine, an association of critical care specialists, states that there should be relentless monitoring of ICU. The association has set its criteria according to WHO’s standard and developed countries’ practice to manage the critical care sector which is totally neglected by the ministry of health.

The ICU needs skilled manpower to help the patients’ body organs operate artificially. Because those admitted to ICU are in a life or death situation, it requires more manpower than other wads.

The ICU should have the provision of mechanical ventilation for artificial breathing, hemodialysis service and medicine for high blood pressure at all hours. Moreover, critical care physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, dieticians, pharmacists and other health workers are also essential at all hours.

According to NSCCM’s criteria, a critical care physician should lead the ICU. But in hospitals outside of Kathmandu, general surgeons and anesthesiologists are handling the ICU’s responsibilities. In a majority of hospitals, however, even that manpower is lacking.

Nepalgunj’s Bheri Hospital, Biratnagar’s Koshi Hospital, Pokhara’s Transmissible Disease hospital, Birgunj’s Narayani Hospital, Dhangadhi’s Seti Provincial Hospital, among other referral centers, do not have level-3 ICUs. Hospitals except for Koshi are running without critical care physicians.

“In truth, when patients at critical care die, people don’t pay much attention because they think the patients are already in danger,” says Pandey, the anesthesiologist at Bheri Hospital, “but it’s regrettable to think how many patients died because of a lack of treatment at ICUs.”

The Seti Provincial Hospital, which is the referral center for Far-West’s nine districts, has three anesthesiologists assigned to operate 20 simple ICUs. “We need at least 20 to make it function properly,” says anesthesiologist Kapil Gautam. “But the concerned authorities have not paid attention to increasing the manpower according to equipment.”

Pokhara’s communicable disease hospital has only one anesthesiologist, Dr. Sachin Koirala. Because the whole city has only one anesthesiologist, quality service to patients in need has become a pipe dream. Dr. Koirala says that if there were four more anesthesiologists like him that would help to ease the burden.

He adds that for a lack of level-3 ICUs, quality service has become the stuff of dreams. “We have had to become meek spectators to the reality of patients’ predicaments,” he says.

The NSCCM standard has it that the incoming patients at the emergency unit should be treated not by general physicians but by critical care physicians. Dr. Pandey says that if critical care physicians delay their service by even 15 minutes that may lead to a patient’s death. Dr. Pandey, who witnessed a massive loss of lives during the second wave of the pandemic, is the sole anesthesiologist working at Bheri Hospital’s critical care unit. The hospital has a vacancy for two more anesthesiologists that remains unfulfilled. Dr. Pandey has solely handled both ICU and operation theatre.

During the peak of the pandemic, a team led by Dr. Prabin Mishra, an anesthesiologist at Karnalai Health and Science Academy, came for help, said Dr. Pandey, adding that the hospital requires at least 10 critical care specialists during pressure. Bheri Hospital’s request for manpower with the government at the time when Nepalgunj became the ‘hotspot’ of coronavirus infection remains unheeded.

“Even in normal situations, five anesthesiologists like me are required in the hospital,” says Dr. Pandey. “You can imagine what the situation was when I was alone during the peak of the pandemic.”

In Birgunj’s Narayani Hospital, which employs 15 general physicians, there are two anesthesiologists. Of them, one was recently added on a contract basis. Dr. Prabhat Adhikari, who was alone during the peak of the pandemic, laments that a dire situation like this hasn’t fallen on authorities’ priority.

In July 2020, Birgunj was becoming a hotspot for coronavirus infection. Because people were dying of the virus across India, there was fear in the air in Nepal. At the same time, Dr. Adhikari got infected himself and had to isolate. But as the patient footfall increased, he couldn’t stay away from his duty.

He says that the situation arose because of a lack of manpower in critical care service. “The situation is the same one and a half year hence,” he says. “The situation of our critical care service is unspeakable. If the pandemic gets worse again, we don’t know how to save people.”

Rupesh Gami, a critical care physician at Koshi Hospital, says that the equipment at the hospital have been shelved away. “The reality is such that even if we had equipment, patients died because there was no one to operate them,” he says. “The irony is such that equipment is being purchased to gobble up commissions but manpower remains the same.”

Lumbini Zonal Hospital shares Koshi’s predicament. The hospital, which has a 30-bed ICU, had nine vacancies for anesthesiologists but only four are employed. Of them, only one is under the government vacancy.

Rajendra Khanal, medical superintendent at the hospital, says that ten anesthesiologists are required even in normal situations. Because there’s no official standard for ICU, the situation across the country is a mess. “Neither is there a separate critical care unit, nor enough manpower,” says Dr. Khanal. “It is impossible that patients get required care in this situation.”

This illustrates that physicians at critical care across the country have had to remain, meek spectators, while patients died in front of them during the pandemic.

ICUs without guidelines

There are only 26 critical care physicians in Nepal, according to the Nepalese Society of Critical Care Medicine (NSCCM). Almost all of them are employed in Kathmandu.

Anesthesiologists are required to work in critical care in the majority of hospitals. Dr. Hemraj Paneru, Chief Secretary of the NSCCM, says that there aren’t enough anesthesiologists either. According to him, most hospitals lack level-3 ICUs that meet the standards, and even those that do face a severe shortage of staff.

Guidelines for Critical Care Medicine require that an ICU should have a ventilator for every two beds, and a staff nurse with critical care training for each bed. According to the Nepal Government’s Guidelines for Health Institutions 2020, hospitals with more than 50 beds should have ICUs that account for 5% of the total bed count. In large hospitals, level-3 ICU beds should account for at least 10% of total bed capacity. According to the Health Ministry, no hospitals have followed these guidelines.

Subash Acharya, Head of ICU at Teaching Hospital, believes the problem stems from the government’s failure to recognize Critical Care Medicine as a distinct field within the Health Service.

According to Dr. Acharya, expecting critical care in a situation where the government’s health guidelines don’t even specify who should lead the ICU is too much to ask. He says that there is no level 3 ICU without a Critical Care Physician (Intensivist), which is why, with the exception of a few public health institutions, no level 3 ICUs or critical care physicians exist.

There are only three anesthesiologists in provincial hospitals that receive patients from ten districts. “The same anesthesiologist has to cover the operation theater and the ICU, which causes accidents during the patients’ treatments,” Dr. Acharya says, “so why isn’t the government interested in this?”

The government is interested, but only in buying equipment. The Health Ministry has accelerated the process of constructing 1400 HDUs, 180 ventilators, and 250 ICUs. It has not, however, planned how to use existing personnel.

Problems in public policy

According to NSCCM guidelines, a total of 50 nurses are required to run an 8-hour shift ICU with 10 beds. A 12-hour shift necessitates the presence of 40 nurses. Almost all ICUs in Nepal do not adhere to this standard. “The prevalent attitude is that a 10 bed ICU only needs 10 nurses,” says Dr. Acharya, Head of ICU at Teaching Hospital.

The Health Ministry has not made it mandatory for a critical care physician to run an ICU, and it has also not specified the qualifications and experience required of critical care nurses.

Kabita Sitaula, Chairperson of the Critical Care Nurse Association of Nepal (CCNAN), says that in other countries, one is allowed to work in an ICU after working in the general ward for two years and completing critical care training. In Nepal, after passing the SLC examinations, one can begin working in the ICU after completing the PCL nursing course.

“This is also why unusual events occur within the ICU,” Sitaula explains, “but these events are dismissed as normal, claiming that the patient’s situation was critical. This is a very risky practice.”

Inside an ICU, a physiotherapist should always be present alongside the doctor and nurse. However, no hospital in Nepal has a dedicated physiotherapist in its ICU. A physiotherapist in an ICU must assist patients with multiorgan failure in exercising their organs. These types of exercises aid in the recovery of critically ill patients. However, not all ICUs in public hospitals have a physiotherapist.

The presence of a Dietician and a Pharmacist inside an ICU is equally important for the improvement of the patient’s health. In the ICU, a dietician works alongside the physician to ensure that the patient is getting enough nutrition.

Similarly, a pharmacist calibrates medicine doses and administers them to patients. However, most hospitals in Nepal lack this kind of manpower. Because the government has not specified any job openings for critical care physicians, critical care nurses, physiotherapists, dieticians, or pharmacists, ICUs are operating outside of the required guidelines. According to Dr. Hemraj Paneru, a critical care physician, there will be no advancement in ICU care as long as critical care is not treated as a separate field.

“On the one hand, ventilators provided by donors and purchased by the government are sitting idle, and on the other hand, patients are dying due to a lack of critical care,” Dr. Paneru says. “It is a huge misfortune that no attention has been paid to the issue of manpower.”

Why is Critical Care required?

Critical Care Medicine is the field of medicine that provides immediate treatment to critically ill patients who have problems with various organs of the body. An ICU should have provisions for artificial breathing or mechanical ventilation to assist the running of failing organs while the major disease is being treated, blood pressure medication, hemodialysis, and so on.

According to doctors, ventilators to support the lungs, dialysis to support the kidneys, and medicines to support the heart should be readily available in critical care medicine. Similarly, patients who have been injured in an accident should be treated as soon as possible with blood transfusions and other treatments.

Critical care physicians, according to Dr. Paneru, save lives by quickly utilizing existing technology and medicines to contain the patient’s infections and support organs that are not functioning properly.

Even though there is no exact statistic, the hospital faces a daily shortage of beds for patients in need of critical care, according to Dr. Paneru, Head of ICU at Teaching Hospital. According to a Lancet Journal article titled “Global Burden of Disease Study 2016,” the leading causes of death in Nepal are disease of the blood vessels of the brain, long-term disease of the lungs, injuries from road accidents, premature births, suicides, and a decrease in oxygen as blood vessels in the heart narrow.

According to a study conducted by Nepal Injury Research, the emergency wards in two hospitals in Hetauda received 33 thousand people in a year, 11 thousand of whom were injured patients. Two thousand of the eleven thousand people were injured in traffic accidents.

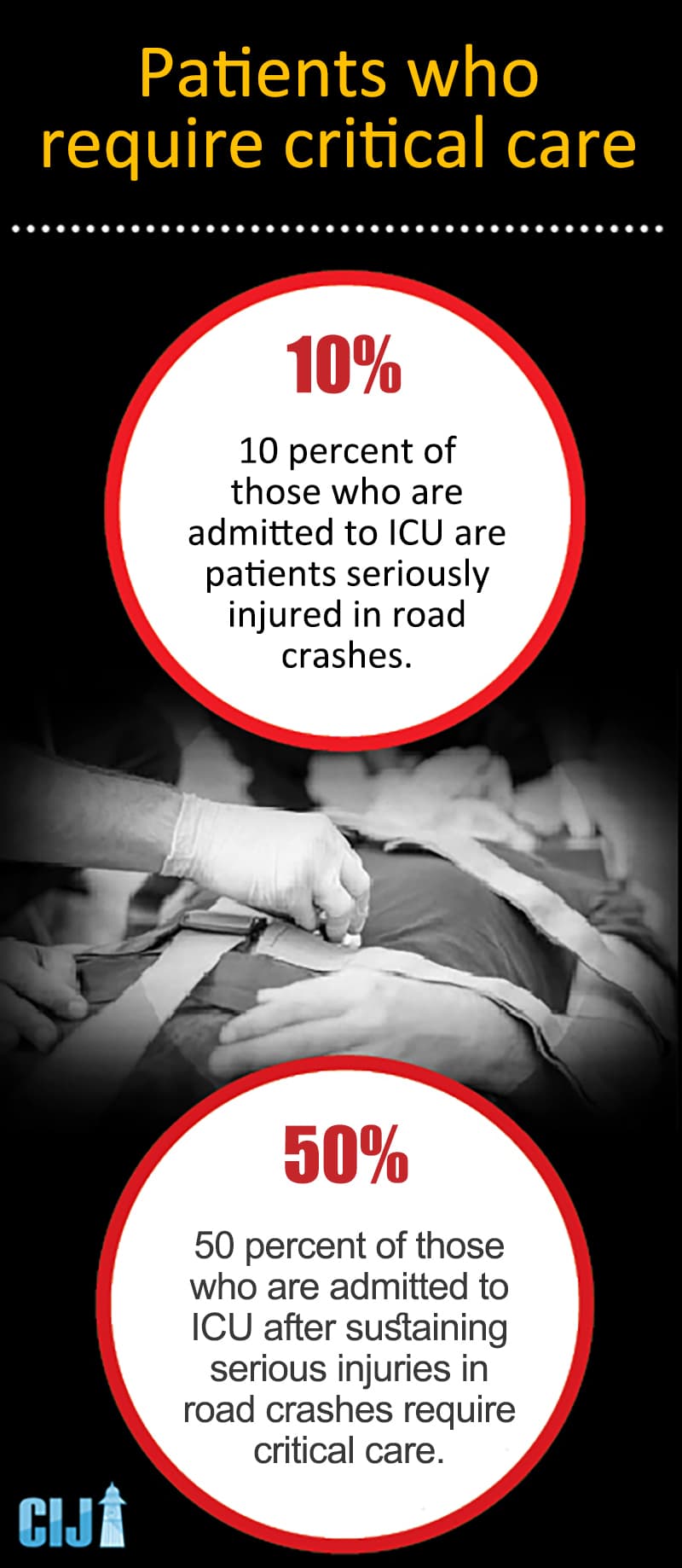

According to Dr. Pushpa Raj Panta, a road safety expert, 10% of all people who arrive in Nepal’s emergency rooms are serious patients injured in road accidents. He says that half of the seriously ill patients require trauma critical care; if those injured can be transported to a hospital within an hour, a large number of deaths can be avoided.

“Accidents have been increasing across the country,” he says, adding that this necessitates an increase in the number of hospitals providing critical care across the country.

Dr. Pramesh Bahadur Shrestha, the first person to complete a DM (a three-year course after an MD) in Critical Care, says that the Corona Pandemic has increased the need for the field in Critical Care and ICUs. He believes that Nepal, like other South Asian countries, is seeing an increase in cases of infections in the lungs, intestines, and road accidents, which is why critical care is essential.

“People who have been in accidents and have broken their ribs or have partially or completely lost consciousness due to blood clots in the brain should only be treated in critical care,” he says. “Patients who have blood clots in their liver, lungs, and other organs due to injuries should also be treated in critical care.”

“Local Level as Level One”

ICUs require not only a laboratory, critical care physician, critical care nurse, physiotherapist, pharmacist, and dietician on a 24-hour basis, but also health professionals and intensivists in cardiology, nephrology, and orthopedics. This means that critical care necessitates highly specialized personnel and equipment.

The federal government’s priority of only collecting equipment has caused problems in Nepal’s critical care services. What role do local governments play in this situation?

“The local level cannot afford critical care, which requires highly specialized manpower and billions of dollars in funding,” Critical Care Physician Dr. Paneru says. “It will be too ambitious to expect the local level to provide effective critical care when the federal government has been neglecting it.”

According to Dr. Paneru, the development of critical care should occur concurrently with the development of other fields. He adds that in order for citizens in different locations to receive equal critical care services, the referral mechanism should be improved. “Unless the referral mechanism is improved, it will remain impossible for people from villages to receive critical care,” he says.

It is obvious that critical care service will improve if the local level takes responsibility for Level 1 ICUs that fall under its jurisdiction and then refers patients to Level 2 and 3 hospitals.

However, this will necessitate coordination among ICU mechanisms across the country, according to Dr. Acharya, Head of ICU at Teaching Hospital. According to him, there is currently no coordination among ICUs in the country. Patients move from one hospital to another based on their needs. There is a high risk of patients dying on the way to hospitals and not being able to get ICU beds even after they arrive at another hospital in this process.

“Patients die prematurely after spending time that could have been spent treating them on the roads,” Dr. Acharya says. “The coordination between ICUs can be increased by improving the referral system.”

According to Dr. Paneru, it is currently impossible for local governments to run Level 3 ICUs. He says that the feasible solution is for local governments to run Level 1 and 2 ICUs and improve the referral system. Many lives, he believes, can be saved by referring patients who are unable to be treated in Level 1 ICUs to Level 2 ICUs, and then to Level 3 ICUs.

“All patients who require emergency care do not require Level 3 ICUs,” he says. “The mechanism that refers patients who cannot be supported by Level 1 or 2 ICUs must be improved.”

Patients who do not have multi-organ failures and do not require surgery for their injuries, according to him, are kept in Level 1 with close monitoring while receiving oxygen to prevent further complications. In Level 2, patients with organ failure are kept under the direct supervision of health professionals using artificial solutions.

Dr. Paneru believes that building Level 1 ICUs in primary level health centers, Level 2 ICUs in district hospitals, and Level 3 ICUs in provincial hospitals that require specialized manpower, technology, and laboratories is the way to go. “The referral mechanism should also be made efficient concurrently,” he says.