Farms in Syangja’s Putalibazaar are under assault from gangs of roving monkeys that destroy all the crops, leaving farmers with little to harvest.

Dinesh Kafle |CIJ, Nepal

Laxmi Sapkota learnt to use a slingshot in her forties.

For most of the summer last year, she spent her day chasing away monkeys from her family farm in Durganagar, Putalibazaar Municipality-1, Syangja.

A person can chase one monkey away by shouting “la hai, la hai“, a few by threatening them with a stick or throwing pebbles at them. But what can someone do when faced with the challenge of chasing away an entire troop of a dozen monkeys all day?

That was when Sapkota bought a slingshot. She learnt how to grip it by the base, hold a pebble in the leather pouch attached to a rubber strap, pull the strap to her chest and then release it. She missed her targets more often than she hit them, but at least the monkeys ran away.

Sapkota grows maize on a piece of land tillable by a yoke of oxen in a day – known as ek hal ko melo in the farmer lingo. By the end of the harvest season, she would have produced about 20 doko (around 4 quintals) of maize seeds, enough to prepare saatu and chyakhla for her family of five and cattle for a year. But first, she would have to keep the monkeys away from the farm.

Each time Sapkota chased the monkeys away with her slingshot and went home, they returned.

Frustrated, Sapkota even turned to more unorthodox methods. She had heard anecdotes about how monkeys were intimidated by men, so she took to patrolling the farm in daura suruwal and dhaka topi. For a while, she thought that she had tricked the monkeys into thinking that she was a man but the monkeys were clever and saw through her disguise. They instead turned more aggressive.

All Illustrations: Nilam Bhurtel

At the end of the season, all she had were maize stalks, sheaths and cobs, but no grain.

“Even if someone asked for a single grain of maize to use as medicine, I couldn’t give them any,” Sapkota told the Centre for Investigative Journalism (CIJ).

Like Sapkota, numerous other farmers in Durganagar are afflicted by the same problem – an invasion by monkeys from the nearby jungles. In the summer of 2021, Durganagar awoke every morning to shouts from residents that the monkeys had arrived. For the better part of the day, the conversation revolved around the damage caused by monkeys. They shared anecdotes about their encounters with monkeys in the times gone by. And they spoke about how farmers in places such as Dyangdi, Komla, Kaule, and Arbhyang villages, all within 10 kilometres of the district headquarters, had stopped planting crops altogether due to the monkey raids. In the long run, locals worried that this would lead to changes in their patterns of habitation and agriculture.

Both locals and experts attribute the monkey invasion to changes in Nepal’s demographic profile owing to internal rural-to-urban and foreign labour migration. As per a preliminary report of the 2021 census, in the past 10 years alone, the urban population has grown from 63.19 to 66.08 percent, whereas the rural population has declined from 36.81 percent to 33.92 percent. These changes have left rural agriculture in disarray as farmlands turn fallow. It is this paucity of food in the hinterlands that, according to experts, has pushed monkeys from rural areas to semi-urban spaces like the hills around Syangja Bazaar, where monkeys were a rarity until a few years ago.

According to Mukesh Kumar Chalise, professor (retired) of zoology at the Tribhuvan University, earlier, the monkeys would raid rural farms, which were closer to their natural habitats and provided easy access to food. But now, with rural farms in decline, the monkeys too have migrated to semi-urban and urban areas, leading to more conflicts between humans and primates in many parts of the country.

“The natural jungle has also expanded due to a decline in agricultural activities, attracting the monkeys to buffer areas between human settlements and jungles,” said Chalise.

Chalise, however, acknowledges that it is unclear whether the number of monkeys has grown exponentially or if they’ve just become more aggressive. This is because there is no data on the country’s monkey population. The first step towards mitigating the monkey problem, he says, is to count the monkeys.

“The monkeys of the Rhesus macaque species procreate in shorter durations if they have easier access to food. This may have led to a slight increase in the population of the monkeys, although we cannot make definite claims without a census,” he said.

Toyanath Paudel, chief forest officer at the Syangja Division Forest Office, affirms that there is no official data on the number of monkeys in the country. Lacking statistics, authorities rely mainly on hearsay and anecdotes to devise alleviation measures.

“Yes, there is a need for the forest ministry to conduct a census to fully assess the diversity and ecosystem of the animals. But censuses are only conducted for protected animals like tigers, rhinos and musk deer,” said Paudel.

But Paudel, too, believes that the monkeys are a symptom of much larger changes, namely migration and economics.

“We are fast changing into urban beings from rural ones. Farms in rural areas are turning into jungles after staying untended for so long,” Paudel said. “We must increase human activities in the peripheries of the jungle, such as by felling uneven trees to thin out the trees so that the monkeys migrate to the inner depths.”

The monkey menace

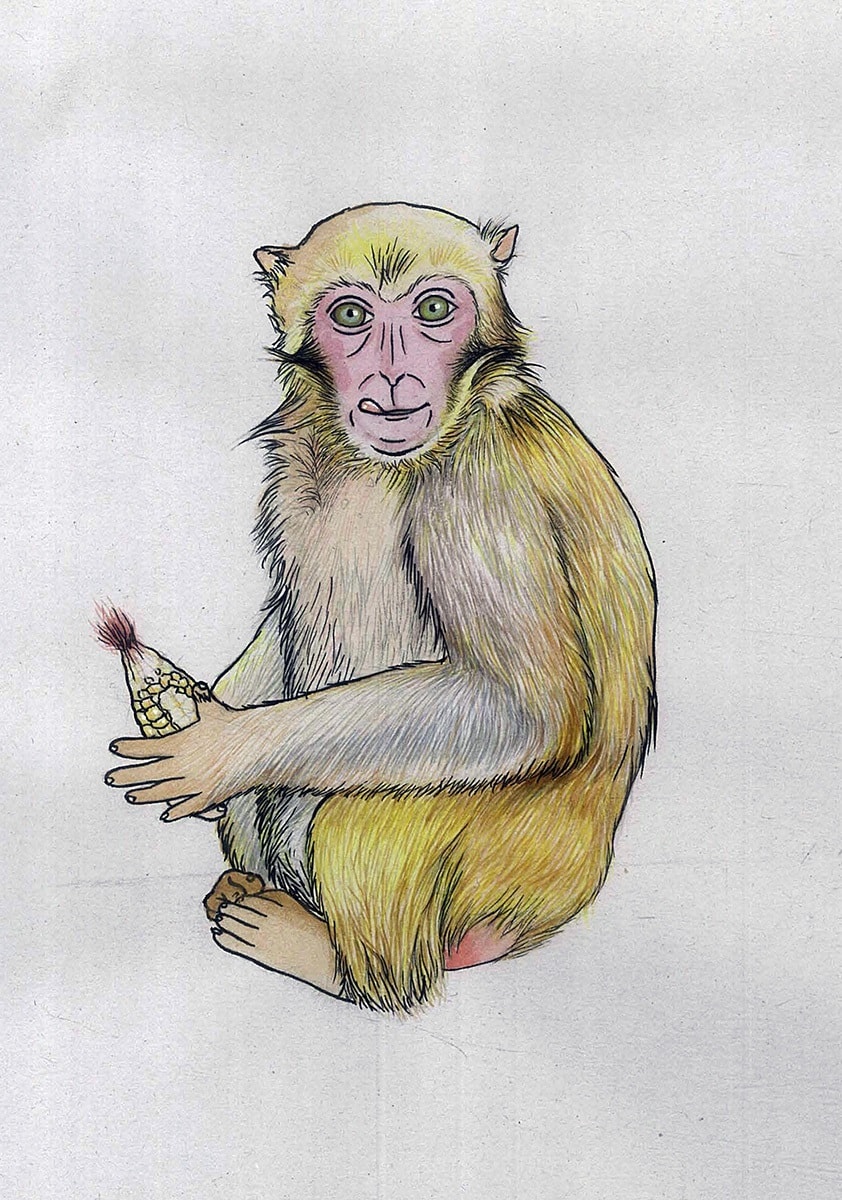

Nepal is primarily home to three species of monkeys—the Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), the Assamese monkey (Macaca assamensis) and the Hanuman langur (Semnopithecus entellus).

According to Chalise, while the threat of the Hanuman langur and the Assamese monkey is smaller, it is the Rhesus macaque, known locally as rato bandar for its dark pink face and buttocks, that inflicts the most damage on crops. The macaque often travels in troops of anywhere between a dozen and a hundred individuals. A farm being raided by a barrel of monkeys appears awash in a sea of grey heads, leading farmers to call them hajariya— or those that come in the thousands.

But it doesn’t always take a troop to wipe a farm clean. In some cases, a lone monkey, known as ekley bandar, can cause significant harm if it can spend hours on a farm, tasting and tossing hundreds of growing corn cobs.

Although government agencies do not have any aggregated data on the number of monkeys or the damage they cause, a sampling of field-specific data from various parts of the country helps gauge the magnitude of the problem.

According to a 2017 study on crop raids by Rhesus macaques in Kaski district, the crops most frequently raided by monkeys were maize (31 percent), potato (30 percent), wheat (17 percent), cauliflower (15 percent), and rice (7 percent). Thirty-two percent of the 60 households surveyed reported losses of Rs20,000, while a further 30 percent reported losses between Rs10,000 and Rs20,000. Similarly, in a 2016 study on crop raids by Assamese monkeys along the Budhigandaki River in Dhading and Gorkha districts, farmers reported crop losses of 234 quintals from an expected yield of 951 quintals in 32 hectares of crop land. Farmers in Baglung and Parbat districts reported a crop loss of 120 quintals out of an expected yield of 688 quintals in 61 hectares.

Authorities clueless, farmers desperate

Keeping the monkeys in the jungle is key to keeping farmers on their farms, thereby ensuring the security of their lives and livelihoods. But despite being well aware of the losses farmers have been facing at the hands of the monkeys, the authorities appear clueless about how to deal with the problem. None of the public officials or elected representatives CIJ spoke to denied the existence of the monkey menace, but they had little to show, even as they claimed that they were in the process of devising mitigation and adaptation strategies.

“We are aware that the monkey raids have become a huge problem in semi-urban and rural localities of the municipality, but the response is quite complicated,” said Purushottam Sharma, chief administrative officer of Putalibazaar Municipality. “It is not possible to stop monkeys from raiding crops by putting up fences nor is it allowed to kill them using pesticides.”

The Gandaki Province Ministry of Agriculture too is aware of the problem and how it has gotten out of hand in the past five years, according to Shabnam Siwakoti, secretary at the ministry. But the institution had not made any real attempt at easing the trouble caused by the monkeys.

“Wherever we go, farmers tell us about the damage caused by the monkeys. The provincial government certainly knows of the menace, but we have yet to come up with a specific programme aimed at controlling it,” said Siwakoti.

With people’s representatives and administrative officials unable or unwilling to deal with the problem, the farmers have been left to fend for themselves. Desperate, they’ve turned to more and more extreme methods.

Last July, a farmer from Durganagar who is in his early forties attempted to feed monkeys poisoned bananas. But he was too late, as the very day he returned from the market with bananas and a pouch of rat poison, he found that the monkeys had already ravaged his maize farm.

“There was no point in killing the monkeys anymore as there was no maize left on my farm,” said the farmer who wished to remain anonymous.

In Araudi village, in Putalibazaar Municipality-2, a monkey carcass had reportedly been hung from a tree to scare the others away. When CIJ spoke to the locals, they first feigned ignorance. But upon probing, a 25-year-old man from the village who also did not wish to be named conceded that they had indeed hung a monkey from a tree. He, however, insisted that the monkey had been killed by a dog and not by humans.

Deputy Superintendent Rajendra Prasad Adhikari, chief of Syangja District Police Office, said that his office was not aware of such an incident but warned that it is illegal to kill monkeys as it is a protected species.

Not all monkeys are protected though. Only the Assamese monkey is protected under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1973. The farmers in Putalibazaar Municipality, however, are not aware of the difference in species and believe that killing any monkey is illegal. Yet, they are willing to do anything to safeguard their crops.

Counterproductive measures

The local authorities have attempted to take some form of action, but they have been largely ineffective and, in some cases, even counterproductive.

“There isn’t much we can do to control the monkeys,” said Paudel, the chief at the Syangja Division Forest Office. “The only pragmatic solution we have is to chase the monkeys away whenever they come raiding. We do not have any means of catching and holding the monkeys, as it is impossible to do so.”

Chasing them away, however, is just a temporary solution, as the primates simply move to another neighbourhood. Those who live in the lower belts are affected the most, leading to resentment against those who live at higher levels.

“The monkeys driven away from Gahate Village come straight to Durganagar in a couple of minutes, jumping from one tree to another,” said Laxmi Sapkota. “We can’t chase them back uphill, so we are the ones who encounter the most damage.”

In the past few years, the Putalibazaar municipality has distributed ‘scare guns’ to farmers as a temporary relief tool. A scare gun, also known as a scatter gun, is a gas-powered ‘gun’ that produces a loud noise to scare away birds and pests from farms. In the fiscal year 2020-21, the municipality purchased 330 such guns, spending an average of Rs800 on each one, and distributed them through farmers’ groups and Tole Development Groups. However, the monkeys quickly realised that the guns were harmless.

“The guns worked for a year, but now the monkeys have gotten used to the sound of the gun and do not run away,” said Sharma, the administrative officer at Putalibazaar Municipality.

Siwakoti, the Gandaki Province Agriculture Ministry secretary, believes that insurance and compensation policies are necessary.

“But the Agriculture Ministry isn’t the only one responsible; this is an issue for the Forest Ministry in equal measures. So there is a need for both ministries to develop a common plan to tackle the menace,” she said. “We have held talks informally at various forums, but nothing concrete has been done yet to formulate mitigation policies and plans.”

Even if the ministry comes up with a compensation plan for affected farmers, their previous losses will not be compensated as no government entity has kept a record.

The Wildlife Damage Relief Guidelines, 2069, prepared by the Ministry of Forest and Environment, does not include crop depredation by monkeys among the damages eligible for compensation, even as it includes elephant, rhinoceros, tiger, bear, snow leopard, wild boar and a few other wild animals.

Another reason why the ministry had not helped the farmers deal with their losses, Siwakoti said, was because the farmers have yet to put forth their concerns in a coordinated manner.

“We have a policy of providing compensation in cases of disasters. We provide compensation in cases of the death of cattle and poultry. However, the damage caused by monkey raids is not part of the disaster management and compensation programme yet,” said Sharma, the chief administrative officer. “So the municipality has not kept any record of the financial loss suffered by farmers due to crop raiding by monkeys.”

When CIJ met Sharma in July last year, he said that the municipality had allocated a budget to mitigate the monkey menace, although he conceded that they had few ideas on how to spend it.

“We have a small amount of Rs9 lakh under the heading ‘monkey management’, but we have yet to think about what to do with it,” said Sharma.

When CIJ contacted Putalibazaar Municipality in the first week of March this year to update how the budget had been spent, Ramesh Gharti, who has now replaced Sharma as the chief administrative officer, said the budget remains unspent.

“We are confused about what to do with the budget. We will also stop distributing sound guns this year because the monkeys have got used to the sound. So the budget remains unspent, and we will spend it only after we come up with effective ways by conducting research and consulting with experts,” Gharti said.

The Syangja Division Forest Office, however, has been taking some steps towards dealing with the problem. According to divisional forest officer Paudel, in the past three years, his office has ensured that at least a quarter of saplings distributed by the office have been targeted at dealing with the monkeys. The office has distributed lemon, timur, harro, barro, gooseberry, litchi, guava, jamun, and jackfruit saplings to 1,200 farmers, who have been planting these within the forest so that the monkeys have a ready source of food and won’t have to raid farms.

“We have distributed 23,200 plants of timur mainly in monkey pocket areas such as Bheerkot Municipality, Aandhikhola Rural Municipality and Arjun Chaupari Rural Municipality,” said Amar Bahadur Parajuli, a staff member at the planning section of the Syangja Division Forest Office.

But for farmers like Laxmi Sapkota, planting fruit trees to lure away monkeys is a fanciful idea.

“It takes years for the fruit trees to grow,” she said. “By the time the monkeys learn to rejoice in the fruits in the forest, we will be long gone.”

A common pursuit

Kamal Parajuli, a businessman and farmer from Putalibazaar-1, Durganagar, lives just a few minutes away from Laxmi Sapkota. In July 2021, the summer was at its peak, and so was the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. The pandemic had forced him to shutter his furnishing store in Ghumti Bazaar, leaving him with enough time on his hands to become a full-time bandar heralu, or monkey watcher, a local term for those who spend their days chasing away monkeys.

Due to Parajuli’s vigilance, his family could harvest a decent amount of maize at the end of the season, although his farm had not remained entirely untouched by the monkeys. The primates raided Parajuli’s farm four times that summer, whenever he was away for his lunch or tea breaks. Those few minutes were all it took for the monkeys to wreak havoc on the farm. Once, Parajuli returned to the farm after 20 minutes to find dozens of partially eaten corn cobs all around.

“I wish the monkeys had eaten all of the maize, filled their stomachs and gone away,” said Parajuli.

But monkeys are fickle eaters. They would bite into a cob, dislike it and then throw it away, only to bite another one. In this incessant cycle of tasting-and-discarding, the monkeys end up destroying an entire farm within hours.

Even so, Parajuli appeared satisfied with what he was able to harvest last summer, considering how badly neighbours like Sapkota had fared. Parajuli’s success, though, was not his alone. In his desperation to drive out the monkeys, he had formed a working relationship with two neighbouring farmers. The trio worked together to guard their farms and keep their crops safe.

Like Parajuli and his friends, other farmers too have come together to forge functional relationships over a shared desire to fight off the monkey menace. Even those who haven’t planted crops participate in this collective pursuit.

Among them was Dinesh Kunwar, a soldier with the Indian Army in his mid-thirties, who had come home on vacation. When he saw troops of monkeys raiding his neighbours’ crops, he joined in the chase to drive them away, leading him to climb a nearby cliff. Kunwar fell to his death in pursuit of the primates in July last year. In the conflict between humankind and its primate relatives, Kunwar became collateral damage.

“We visited the crime scene, prepared a report, and registered the case as bhavitavya ghatana, an act of no fault, as it is not possible to put monkeys on trial as defendants,” said Rajendra Prasad Adhikari, public information officer at the Syangja District Police Office.

Departures

By the end of last summer, the monkeys had all but disappeared from Durganagar, Devisthan and Araudi villages, leaving the farmers unable to process the suddenness of their departure and harvest whatever they had managed to salvage.

But with winter now giving way to spring, the farmers are readying for another season of cultivation and are already worried that the monkeys will return. Once the seeds have been sown, the monkeys will arrive to dig them up and eat them. When the remaining seeds grow into saplings, they will eat the tender shoots. And finally, when the few remaining plants yield maize, they will eat the maize.

If they can’t find the maize, they will eat – or rather destroy – mangoes, oranges, bananas, bamboo shoots and even gooseberries.