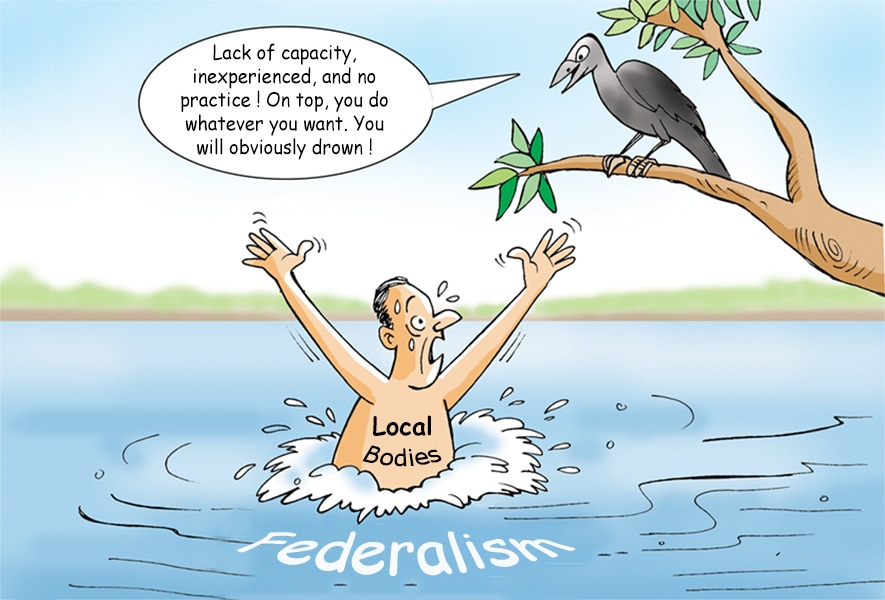

The performance of local governments has been unsatisfactory despite the enormous mandate provided to them, a study conducted by the Office of the Auditor-General claims.

Krishna Gyawali: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Local governments have been given a range of responsibilities, from formulating laws to managing schools, and enhancing farming and animal husbandry to ensuring good governance. The Constitution of Nepal 2015, increased the authority of the local governments. But their efficiency has not seen much change. A glance at the comprehensive study and audit of 27 local levels across the country, released by the Office of the Auditor-General in June-July 2020, is self-evident.

• The internal income of Baitadi District’s Patan Municipality was just Rs2.5 million. The municipality spent Rs6.3 million on the salary of officials in the fiscal year 2018/19. The municipality provided monthly allowances to ward chiefs and members even though its internal revenue was insufficient.

• The internal check-and-balance system of Bhaktapur Municipality was found to be pretty weak. The record of the material property of the municipality is not up to date. The record does not include the details of materials of the erstwhile village development committees and other government offices. The receipt of expenditures was not kept properly. There were records that showed that expenditures were made on credit whereas the money was reimbursed to the staff. The report of the audit says, “A suitable decision should be made towards strengthening the internal check-and-balance system.”

• As per the Local Government Operation Act, 2074, municipalities across the country are mandated to provide building and house construction permission only after the design is passed according to the building construction guidelines. But the Kamalbazaar Municipality in Achham District was not found to have passed the design even until the end of the last fiscal year. There is a risk of damage by an earthquake if houses and buildings are constructed without getting the design passed.

• Local levels at eight places, including in Parwanipur, Gorkha, Dhankuta, Amargadhi, Gaushala, Mohanyal, Khajura and Gurbhakot have not been able to form accounts committees yet, which has hindered the efficiency of local levels.

• Local levels in Gauradaha, Rupa, Mohanyal, and Lalitpur have not been able to form village/city education committees in their local levels. Mithila Municipality has not been able to form a school management committee yet. These local levels have not been able to keep land records of public schools in their jurisdiction.

• Local levels including Phedikhola, Parwanipur, and Gaushala have not made laws related to urban development and building construction, settlement development, and revenue guidelines. In the absence of guidelines, there is no uniformity in the kinds of services provided by the municipalities and rural municipalities.

According to the study of the Office of the Auditor-General, Gauradaha, Gorkha, Phedikhola, Parwanipur and Gaushala have not made any laws related to the management of the services they provide. These local levels have also yet to make laws related to urban development and building construction, settlement development, cooperative operation and revenue guidelines. Similarly, they are yet to make laws on the usage of local infrastructure and service surcharge, which has led to confusion among service seekers about the kinds of services they get and how much they are expected to pay for such services.

According to Ashok Byanju (Shrestha), president of the Nepalese Federation of Municipalities, local governments face legal and practical hindrances to work in full capacity as per the constitution. “Local levels do not have enough staff from the relevant subjects and areas. A total of 102 local levels are being run by chiefs-in-charge. It is due to the lack of manpower that they have not been very efficient at their work.”

The Office of the Auditor-General had conducted a comprehensive study of 27 out of 753 local levels that would represent all provinces, geographies and levels. During the study, it conducted a discussion with 350 stakeholders and studied 1,500 projects. It also analysed the records of the past two years as well.

According to Maheshwar Kafle, the spokesperson of the Office of the Auditor-General, eight of the 27 local levels refused to provide their documents altogether. “The performance of the local levels is pathetic,” Kafle said. “They are terrible at financial management. Their budgets are traditional rather than result-oriented. The study concludes that their performance needs to be improved.”

Projects selected on a whim

The selection of rural and settlement level projects is the most important work of the local levels. The local levels can collaborate with other local levels to run projects that they cannot run on their own. They recommend the projects they cannot handle on their own to provincial governments and even the federal government. The study of the Office of the Auditor-General shows that the local levels in Mohanyal, Parwanipur, Gaushala and Gauradaha selected projects on the basis of requests from ward members. Eleven local levels from Gaushala, Melamchi, Mohanyal, Jiri, Lalitpur, Mithila, and Gorkha, among others, were found to have selected projects through the decision of the council.

The selection of any project should be accompanied by an environmental impact assessment (EIA). However, 19 of the local levels studied by the Office of the Attorney-General were found to have begun projects without completing the EIA. The study pointed out it is wrong of the local level officials, builders and contractors to build the projects thus selected. The study shows how people’s representatives do not even monitor the projects selected for local development. The study showed that only 10 percent of the projects were monitored by the representatives. Although each local level came up with 200 projects on average, they did not seem to run for long.

Consumer’s committees were also found to have subleased their work to contractors. Throughout the country, consumers’ committees were found to have spent Rs1.46 billion on machinery usage in the year 2018/19. The usage of machinery, such as bulldozers and excavators, were seen to have impacted the environment negatively as well as increased hazards.

The study also showed that such activities had inspired the consumers to become agents and rent-seekers. Let us look at an example from Nuwakot. In the fiscal year 2018/19, Bidur Municipality signed a contract through a consumers’ committee to complete a project worth Rs 5.276 million at only Rs 4.980 million. But the consumers’ committee subleased the work to a contractor at Rs1.198 million. The study provides a long list of such discrepancies at other places as well.

According to Krishna Prasad Sapkota, former president of the Federation of District Development Committees, an assessment of the past three years of local levels shows three kinds local levels: The first is excellent and creative; the second is average and works according to instructions; and the third is good-for-nothing and is always looking for loopholes to make a profit. “These three kinds of local levels each occupy one-third of the total local levels across the country. If we do not control the one with selfish motives in time, then they will be the ones in the majority in the future.”

Extravagance abound

The officials of local levels receive allowances as per the provincial laws. But there is no uniformity in such allowances. For instance, the Barahapokhari Rural Municipality in Khotang District has employed three drivers on a contract basis when the rural municipality does not have vehicles at all. Similarly, in the fiscal year 2018/19, the deputy-chief of the Paatarasi Rural Municipality in Jumla District took Rs95,000 as an allowance for presenting policies and programs in the village council. The deputy-chief of Sinja Rural Municipality took Rs2 lakh and the chairperson of Tatopani took Rs95,000 as allowances.

The report of the auditor-general shows that the local levels have not constituted internal auditing units. In the past three years, several local levels have failed to conduct audits of public schools. The local levels have not constituted the audit committee and the good governance committee required for the same. “On the one hand, this shows that the schools have not followed financial discipline, and on the other, the local levels have shown no inclination towards the same,” the report says.

Local levels account for 12 percent, or Rs38.12 billion, of the total Rs132 billion unaccounted expenditure in the last fiscal year. This explains the financial indiscipline among local people’s representatives in the past three years since the country devolved state power to local levels. The Office of the Auditor-General has pointed out that 105 local levels did not convene the council to pass the budget in time, and 68 local levels spent more than the budget passed by the council. According to Balananda Paudel, the then of the Local Level Restructuring Commission, “We keep saying that local levels have failed to do this thing or that because they have this much of unaccounted expenditure. But how do we see the fact that the federal government has more unaccounted expenditure than that of the local levels?”

Paudel, who is also the chairperson of the National Natural Resources and Finance Commission, said the current local levels have done much more than the local levels of the yesteryears that had no constitutional mandate and people’s representatives. “There should be a debate on how much they should have done and what they have not done. But it won’t be right to conclude that they have only created a mess and nothing else.”

Paudel, who led the project that conceptualised the formation of 753 local governments, sounds hopeful about the role of local governments. “We can all imagine what would have happened at a time like this in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic if there were no local people’s representatives,” Paudel said.

Things did not happen as expected

Even after local people’s representatives took over local governments, the governments are yet to increase their efficiency. Bansha Lal Tamang, secretary-general of the National Federation of Rural Municipalities, said “Federalism is a new practice. Moreover, the erstwhile village development committees that did not even have office buildings have been transformed into local governments. So three years is not enough for them to begin working efficiently.”

The study by the Office of the Auditor General showed that the local governments had not monitored whether the medical shops, hospitals, nursing homes had been registered and were operating as per guidelines. “Local levels have not even used their mandate to monitor and regularise hospitals with 15 beds or less and medical shops,” the report says. “This leads to the people being deprived of quality and reliable health care.

According to Sapkota, the former chairperson of the Federation of Village Development Committees, skilled manpower was not sent to the local levels during the adjustment of government officials. The concerned ministries including Agriculture and Animal Husbandry did not allow the transfer of their manpower to the local level. It is only the low-level manpower that have been transferred to the local level. “In such a situation, it is not unusual for local levels to be unable to work as expected. The local levels still suffer from the lack of experienced and skilled manpower.”