Local units, supposed to speed up help, are instead causing trouble for people with disabilities, leaving them bitterly disappointed.

Laxmi Basnet | CIJ, Nepal

On July 12, 2020, the Shahid Bhumi Rural Municipality in Dhankuta appointed Fulmaya Rai as a primary-level teacher to Siddhadevi Secondary School in Saptingtar-7 under relief quota. Fulmaya is a relative to Manoj Rai, the local unit chief. Rai had orchestrated the selection of an able-bodied person for the post reserved for a visually-impaired individual. The Dhankuta District Association of Visually-Impaired organised a press meet to protest against the move.

On January 17, 2019, the Education Development and Coordination Unit, Dhankuta, had provided a relief quota to the school upon a decision by the District Education Committee. The visually-impaired seeking to apply for the post had thus waited for the date of a formal public notice. But the notice was published without informing the job-seekers, and Fulmaya was selected for the position, with officials claiming that no one had applied for it, says Khagendra Yonjan, an advisor to the district-level association of visually-impaired.

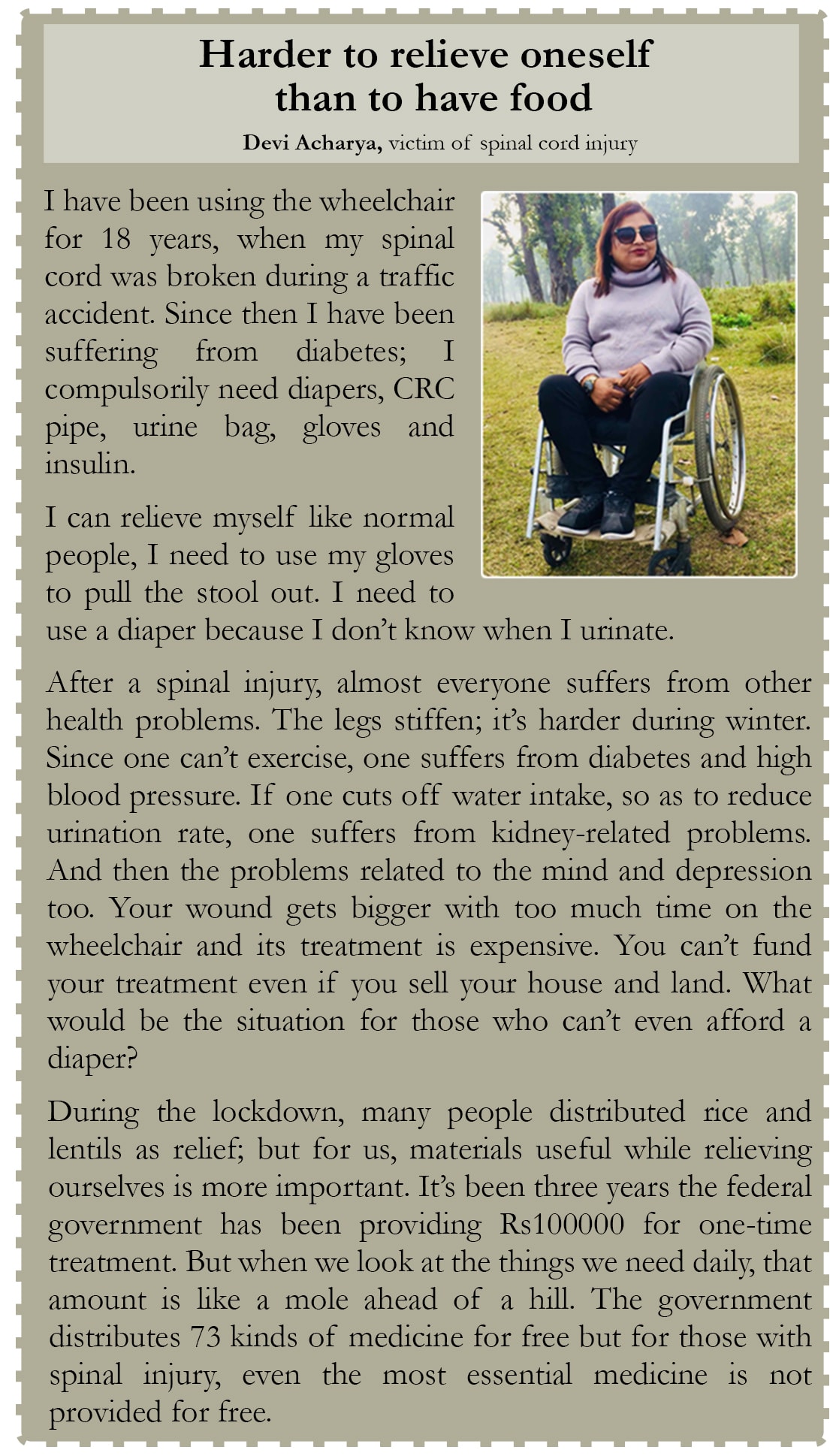

A child studying at Special School. Photo: Urmila KC, Teacher, Special School.

The association had appealed the decision but it went unheeded, leading to a public protest on August 1, Yonjan informs. A day later, the association lodged a formal complaint at the Itahari-based Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA). But the Authority has ignored the complaint despite repeated pleas, says Yonjan.

In Kanchanpur, after a quota for a visually-impaired woman teacher was “lost” in 2017, rights activist Balram Pant launched a fast-unto-death protest. As in Dhankuta, here, too, an able-bodied person was appointed for the position. Likewise, Pant had also informed the District Education Committee and filed a complaint at the CIAA.

Pant broke his fast after two days, after a consensus with authorities that the quota would be “located”. Pant, who is a central committee advisor to the Nepal Visually-Impaired Persons’ Association, says, “In many districts, able-bodied persons close to authorities have been instated for positions reserved for visually-impaired women.”

In July, when the Bhimdatta Municipality purchased wheelchairs for the disabled, it met with protests from the disabled themselves. The reason was the wheelchairs were not fit for use in outdoor settings but instead of the kind used inside hospitals by patients.

The municipality had agreed for the deal with one company but it purchased substandard pieces from another company, says Manoj Chand, a rights activist who had lodged a complaint against the move at the CIAA. “We have a local unit that doesn’t even understand the difference between the wheelchairs used inside the hospitals and ones used by people with disabilities,” Chand says. “What else can we expect?”

Some of the 25 wheelchairs purchased at Rs375000 each were already distributed. The distribution was stalled after it was revealed that some machines were unusable, others damaged, says Dirgha Kumar Swar, another rights activist.

Since the local level elections, Gopal Pun of Baijnath Rural Municipality-4, in Banke, has been demanding for prosthetic legs with the local unit. Pun had lost the lower part of his left leg when he was hit by a truck in 2006. He was provided one prosthetic legs by an organization but it is now damaged. Pun can’t buy one on his own given his impoverished economic background. And with the local level turning a deaf ear, he currently can’t do any work to make a living, he says.

Bulldozer in the house

There were 20 students at a rehabilitation centre for children with mental disabilities in Imadol, Mahalakshmi-2, in Lalitpur. The centre doubled up as a special school and was set up at a public building. On 13 May 2019, a bulldozer raged at the school while the students were at the house. “They ran the bulldozers without informing anyone,” Urmila KC, a guardian, says.

The rehabilitation centre has been operated by Society for the Rehabilitation of People with Mental Disabilities, which is chaired by Nanda Kumar Neupane, ward chief of Mahalakshmi-1. KC adds, “The ward chair said that if the committee doesn’t pay the rent, then the wards 1 and 2 would, and if they don’t either, I will pay it alone.”

But since June 2018, the rent due for the building is outstanding; nobody paid it. The municipality had asked for rent before the bulldozer was run. But since the rent was not paid, today, KC has set up the centre on her own house.

The government has been providing Rs600000 per year to pay for the four teachers, the children’s fooding, and school management. KC, who also teaches, says that she along with two other teachers are not getting paid. “In three years, the municipality provided only Rs375000, VATs excluding,” KC says. “We had expected things would get easier after the local unit elections, but instead they got harder.” The centre also runs “daycare” classes, which give the guardians time to focus on their work while the children are at school. KC has been still running it.

Sirjana KC, secretary of the Mothers’ Association for People with Disabilities, Lalitpur, says that the federal government has stopped providing the funds after the local units were set up, and the local units have not cared either. As a result, the rehabilitation centres and day care programs are on the verge of closure. In another rehabilitation centre, Patan CBR, in nearby Patan, a single teacher is looking after 55 children with disabilities. “Four of the five teachers who were teaching at the centre since its establishment 25 years ago have been fired by the then District Education Office,” KC said. “The office asked for the teachers’ licenses and the budget was stopped after the elections of local units.”

The “disappearance” of the quota

Bhaktapur CBR, a community-oriented rehabilitation centre for children with mental disabilities established in 1985, had been providing free treatment, special education and rehabilitation facilities for over 2000 children. The centre had eight teachers and was providing service to 63 autistic children and 15 with hearing difficulties. When the country adopted federalism, the responsibility for governance of the school went to Bhaktapur Municipality.

On 29 November, 2017, the then District Education Office, Bhaktapur, wrote a letter to the municipality to release the budget to pay the teachers. But the municipality said it hadn’t received the budget and that the position for the teachers was yet to be proved; the quotas were “lost”. Today, the teachers have been working without salaries and the CBR has been managing funds for other needs of the children.

Ramesh Ram Shrestha, coordinator of CBR Bhaktapur, says he has been asking the CIAA and National Vigilance Centre to search the “lost” quotas. “Where did the quotas disappear without our knowledge and permission from the Education Department?” reads a complaint Shrestha filed to the CIAA.

Ramesh Ram Shrestha, coordinator of CBR Bhaktapur, says he has been asking the CIAA and National Vigilance Centre to search the “lost” quotas. “Where did the quotas disappear without our knowledge and permission from the Education Department?” reads a complaint Shrestha filed to the CIAA.

Sudarshan Subedi, a rights activist, says that many community-based rehabilitation centres (CBRs) and special schools are either closed or on the verge of closure. All of this is because the local units have been negligent and many teachers have had to work without salaries, he says. “As a result, the education for thousands of children with disabilities across the country is in jeopardy,” Subedi, a former chair of the National Federation of Disabled, adds. “Even the scholarship opportunities meant for the children have been held by local units.”

The struggle to get an identity certificate

Hemophilia is a serious kind of disability, but those fighting it complain none of the three tiers of government are helping them. The genetic disease that afflicts the males has a high treatment cost. The medicines are hard to get. According to Nepal Hemophilia Society, nearly 700 people are currently fighting the disease in the country.

Bedraj Dhungana, an advisor at the Society, says that one in every 10,000 suffers from the disease, so there might be many undocumented sufferers in Nepal. “We have been able to save the lives of many because the World Hemophilia Society provides funds to treat those who need emergency care, but since even the federal government of Nepal hasn’t allocated any budget for it, we don’t have much expectation from the local government either,” Dhungana says.

According to Dhungana, the Province 1 government has allocated Rs10million for the treatment of the disease. Besides that, none of the federal, provincial and local units have provided any financial support to the sick. “There is a widespread belief among the local government officials that only those who use wheelchairs or are visually-impaired are disabled,” he says.

For the people with disabilities to get help from the government, they should be listed or acquire an identity card. After the federal government decided to stop the monthly allowance of Rs1600 to those listed as “B” grade disability (those with blue certificate) under the Social Security Scheme, the Department of National ID and Civil Registration on April 8, 2020 sent a letter to all local units to stop the allowances for the last quarter of the fiscal year 2019/20. Then all the local units stopped the allowance. According to rights activists, while the government was distributing relief to people, the federal government had stopped providing allowances for the disabled. Following the move, the people with disabilities had staged a demonstration despite the pandemic.

The government has been providing Rs3000 and Rs1600 respectively to those with red and blue certificates. Not just the allowance was stopped amid the pandemic but it also became harder to get the certificate cards.

The 11-year-old son of Bhagwati Dahal, hailing from Tamakoshi Rural Municipality-2 in Dolakha, can’t speak properly and can’t eat by himself. He can’t relieve himself without help from others either. Dahal has now admitted her son, with the autistic conditions, at a special school in Kathmandu. Six years ago, when she went to prepare a certificate for him, the officials provided him with a blue card, saying the disability was minor.

“All the students at the special school with autism have received red cards,” says Bhagwati. “Amid the lockdown, I tried to prepare a red card but the officials from Tamakoshi Rural Municipality dilly-dallied her request, saying a referral from the doctor was necessary.”

But the existing law regarding rights for the disabled states that if there arises a confusion regarding proving the grade of the disabled, the local unit can examine the person at a nearby government hospital.

A 21-year-old woman from Kathmandu Metropolitan City can’t eat or relieve herself on her own since her birth. “My husband left me because of my daughter’s disability,” the woman’s mother said. “The ward chair’s house is right beside mine, and I have pleaded to him to start a day care house for disabled or orphans. But he has completely neglected the request,” she said. The mother, who herself is suffering from diabetes and high blood pressure, hasn’t taken her daughter out for six years.

Likewise, the 19-year-old daughter of Meena Bhandari from Nagarjun Municipality-1 in Kathmandu has Down’s syndrome and can’t speak or eat by herself. After a six-year long effort, she got her certificate only in September this year. “Only when Srijana Miss (the rights activist Srijana KC) came to the school one day and with her help did the ward office recommend for the certificate,” says Bhandari. “She should have got a red card but the ward recommended the blue one, all because she could walk.”

It is because the officials are poorly-informed about mental disabilities, Down’s syndrome, and autism that the people with disabilities have been struggling for years just to get a certificate, says Mukunda Dahal, chair of the Guardians’ Association for People with Disabilities. “There are only a few doctors who understand these conditions, and officials at local units don’t feel like they need help from physicians,” he says. “That’s why because the people with these conditions could walk, the officials provide blue or other cards and not red ones.”

In many cases, even the red cards of people with autism are exchanged for blue cards. “In many special schools and rehabilitation centres in Kathmandu Valley, when the people with these conditions visit to renew their cards, their red cards are taken back and instead they are given blue cards because they could walk,” says KC, the rights activist. “Despite the fact that these children need support 24 hours a day.”

A water tank constructed in Mahalaxmi Municipality, War-2, after demolishing the special school.

Sabita Uprety, who is running a special school for children with autism, says that because even the physicians don’t understand autism, it’s getting hard to get a ID card. “Even though the law dictates that autism is a disability, there are only a few doctors inside the valley who really understand the condition and there are virtually none outside the valley,” Uprety says. She recommends that the local unit officials take the issue seriously since even though the children could walk or speak a few words, they need to be taken care of all the time.

According to the Act Relating Rights of People with Disabilities 2019, among the ten kinds of disabilities, the psycho-social disability is also one. But those with that kind of disability have a hard time preparing an ID. So much so that many local representatives have no idea about the law relating to the rights of people with disabilities. Jagadish Dhakal, a Gorkha-based rights activist, says that while working at the Siranchok Rural Municipality, he had to provide photocopies of the act and methodologies to the local units and its ward offices. “None of the representatives from all eight wards in the rural municipalities had ever seen the act, let alone they be capable of formulating one,” he says.

Matrika Devkota, founder of Koshish Nepal, an organization working towards rehabilitating people with disabilities, says since psychosocial conditions are not something apparent in one’s body, the officials should provide IDs based on the people’s behaviours. “Today, there are five representatives in a single ward. It is not that people with disabilities are everywhere,” he says. “With effort from representatives, ID cards and facilities should be provided considering the behavior and condition of people with disabilities.”

The epidemic of rape and sexual assault

A 23-year woman from Tamakoshi Rural Municipality in Dolakha, who had multiple disabilities, gave unwanted birth to two children out of rape within three years. She had problems with hearing, speaking and other psychosocial conditions. She gave birth to the first child in 2017. The child was dead upon birth. Just before Dashain this year, she gave birth to another child, who is currently under protection of an NGO. Her father says that she has been inoculated with a birth control vaccine for fear that she would be raped again and give birth to another child. “She relieves herself in her own bed but occasionally also gets out of home,” he said. “She is alone at home when we are out for work. Hence, to prevent her from another unwanted pregnancy, we decided to vaccinate her.”

Urmila KC, the rural municipality deputy chair who had met the woman after she was under protection at the NGO, says that her office will try to identify the rapist. “We can’t point a finger at anyone right now, nor has her father,” she says, “But we will make some effort from our side.”

According to the law, it is the responsibility of the local unit to protect women in such conditions, assist for legal treatment for free, and to provide ID cards. But in this case, the rural municipality has paid no attention. The victim has no certificate identifying her as a person with disability. Her father says that when they went to the rural municipality to prepare the certificate, he was returned, saying he needed a recommendation from a “big doctor”.

In Sunsari, too, when a hearing-impaired teenager was raped by a neighbour six months ago, the society came as one to recommend “reconciliation”. The victim’s mother, a single woman, says that none of the representatives helped the family to file a complaint to the police. As a result, she has had to struggle not just against the perpetrator but also with the society, the mother says. “They tried to bribe me saying I would get Rs 1 million,” she said. “But what we want is justice.”

The Act relating to rights of people with disabilities has it that the state should help the victims of rape and sexual assault get legal treatment free of cost. The act further states that the government would record incidents of rape and sexual assaults, help take the case to court, protect the victim, provide relief, and rehabilitate. The act has assured further rights as well. The act and methodology explicitly states that it is the responsibility of the local unit to implement the law. But many representatives are ignorant of the act.

“Vote politics” in providing ID

Prior to the implementation of federalism, the district-based Women and Children’s Office would provide disability ID cards. According to the Act Relating to Rights of People with Disabilities 2017 (first amendment), the responsibility was now transferred to the local units. In each local unit, the coordination committee, led by the deputy chair, decides on the kind of ID to be provided to the person with disabilities.

Lochan Bhattarai, secretary of the Forum of Human Rights for People with Disabilities, Nuwakot, says that there have been many irregularities within local units while providing IDs—those who should have received blue certificates have been given red one and so on. “With the set up of federal structure, the compulsion to visit district headquarters to prepare certificates have been solved, but those who should get one haven’t got it, and others have been unfairly benefitted,” he says.

Rajesh Sah, Province-2 secretary of Federation of People with Disabilities, says that local units have been distributing certificates to attract votes. Chair of the federation Kiran Paswan too says that there have been many irregularities regarding certificate distribution, those who should get it haven’t, those who shouldn’t have. Moreover, in many local units, the coordination committees for certificate distribution are yet to be set up.

Rama Dhakal, deputy chair of National Federation of People with Disabilities who walks with prosthetic legs, shares a bitter experience where she couldn’t meet the local representatives. In most cases, the local unit chief and other officials have their offices in the top floors, and the infrastructure at the buildings are not favourable for those with disabilities. “If they had their offices on the ground floor, it would help not just the people with disabilities but also senior citizens and pregnant women,” she says.

Even the country’s central administration centre Singha Durbar itself is not disabled-friendly, let alone the slogan of “Singha Durbar in every village”. Birendra Raj Pokharel, who has done a PhD on the subject of how the use of information-technology can streamline the role of visually-impaired in development, says, “We have repeatedly requested that documents in government websites should be in English or in Unicode, but the officials at the ministries never seems to understand. Maybe if they start it, local units too would follow suit.”

Lakshmi Maharjan Devkota, who works towards the rights of those who can’t hear, speak or both, says, “If one goes to the Ministry of Women, one would have to take a translator with them, or communicate via writing. Those who can’t write and can’t take translators also have their work at the ministry. If this is the situation at Singha Durbar, what can we expect from local units?”

People with disabilities—neglected from all spheres

According to the census of 2011, 1.94 percent of total population of Nepal (513993 individuals) are those with either one or multiple disabilities. Nearly half of them are women. A total of 36.32 per cent had disabilities relating to body; 18.46 relating to eyes; 15.45 hearing-impaired; 1.48 were those who couldn’t hear or see; 11.46 percent related to vocals; 6.04 percent with mental disabilities; 2.90 with psycho-social disabilities; and 7.52 percent had multiple disabilities.

“Since the onset of federalism, the programs meant to empower people with disabilities have stopped altogether,” says Raju Basnet, general secretary of National Federation for People with Disabilities. “The participation of people with disabilities has been annulled right from the planning process.”

A report released by the National Human Rights Commission in September this year related to the state of human rights of people with disabilities states that local units haven’t brought any concrete program in protecting and promoting the rights of the disabled and poor implementation of the law. The report further adds that the provincial and local units haven’t been attentive enough for the treatment and rehabilitation of people with disabilities, and ignorance of stakeholders regarding the free-of-cost health services for the disabled.

The commission has recommended that the local units’ role regarding the issues of disability be strengthened; provincial governments place the issue on high priority; federal, provincial and local government include disabled-friendly provisions on their laws; and also to amend the existing laws on the issue.