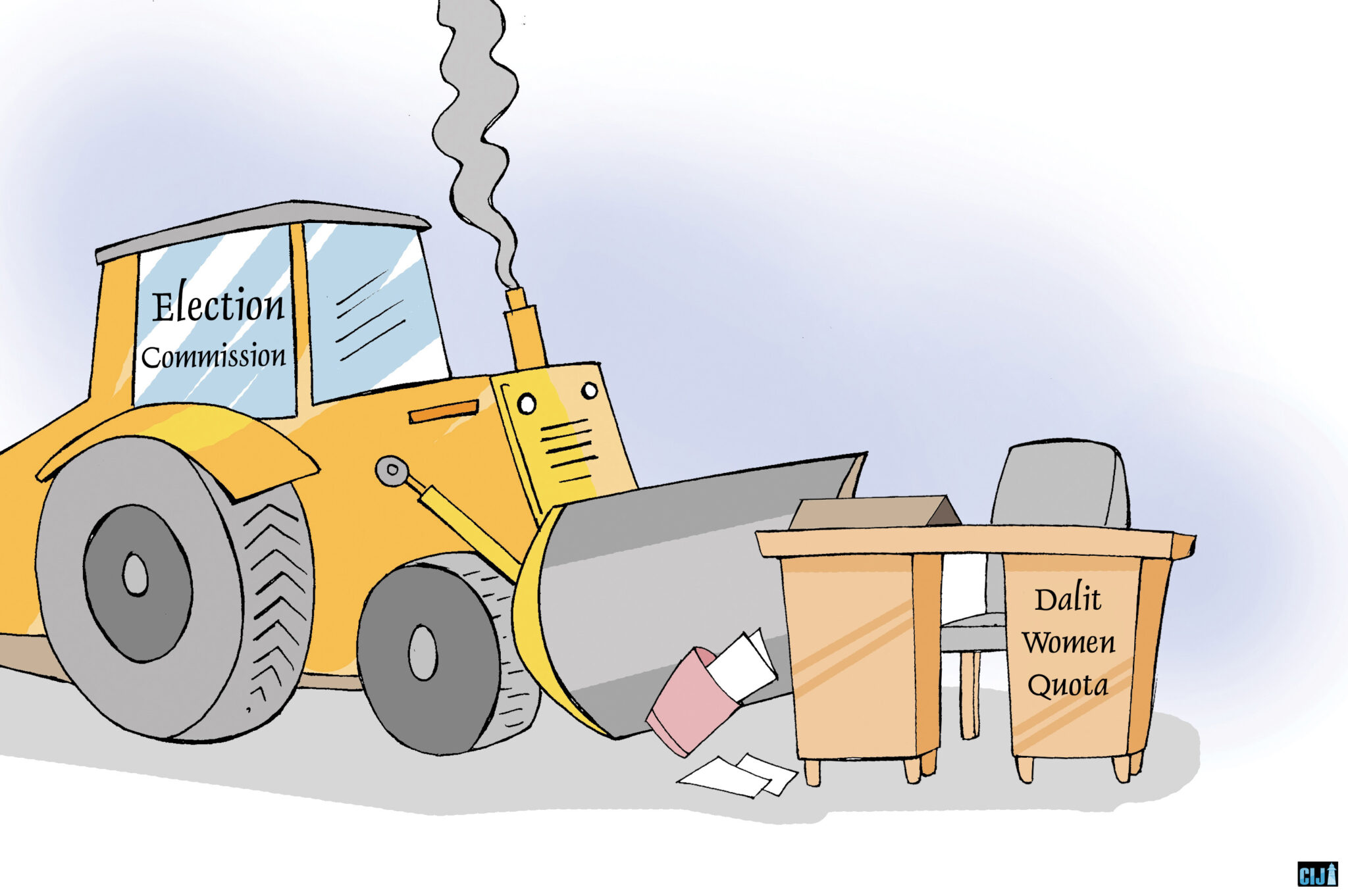

A revelation of how political parties distributed public land to their kith and kins in the name of landless squatters in the last thirty years.

Mukesh Pokhrel: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

On Feb 25, 1990, the multi-party interim government formed after the historic People’s Movement, constituted a Landless Squatters’ Problems Resolution Commission under the chairmanship of Nepali Congress (NC) leader Bal Bahadur Rai to ‘identify and address’ the problems of landless squatters. The Commission, despite formulating the strategy, did not distribute lands to the squatters.

Squatters’ settlement at Naraha village municipality-3 in Tilakpur of Siraha. Photo courtesy: Surendra Kamati

One year later on November 25, 1991, the government formed another commission under the chairmanship of Saileja Acharya, then agriculture minister, for the same purpose. Shares Tarini Dutta Chataut, the then Chief Whip of Nepali Congress at the House of Representatives (HoR): “The intention was to address the squatters’ problems with utmost priority.” In order to ensure precision, the Acharya-led Commission called for applications from landless squatters, and compiled the data. After receiving applications from a total of 263,038 families, the commission scrutinized some 54 thousand 170 applications. It then distributed ‘Nissa’ (evidence of a temporary authentication being provided prior to providing land registration certificates) to 10 thousand 278 families labelling them as ‘temporary’ squatters. Later, the commission distributed 2,296 bighas of land to 1,278 families.

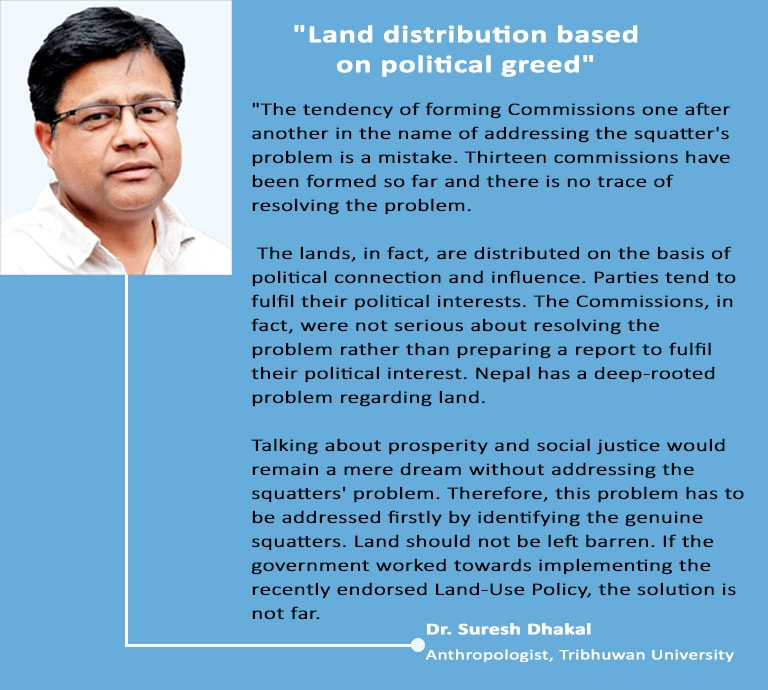

A total of 15 commissions, including those led by Bal Bahadur Rai and Shailaja Acharya, have been formed in the last 28 years with the same purpose. According to the Ministry of Land Reforms and Management, among these, six commissions distributed 46,694 bighas of land to 154,856 families, so far. However, instead of minimizing the problem, it is getting tricky. If the record of the 14th Commission formed on June 16, 2014 led by Sharada Prasad Subedi is to be considered, there is a staggering figure of 861,000 families, who are landless. Interestingly, Minister of Land Management Co-operaitves and Poverty Alleviation Padma Aryal is all set to form another commission to look into the blazing issue. “Discussions are underway to form a Commission to address the squatter’s problems,” says Minister Aryal.

Land confined in papers

Despite distributing considerable bighas of land, the problem of landless squatters still remains complicated. Smelling rat on those commissions’ intention, when we tried to go deep down into the issue, we found out that the commissions, unfortunately, were formed with ill-intentions. Several non-squatter families — mainly the kith and kins of political leaders – were given land ownership certificates.

Consider this: The Landless Squatters’ Problems Resolution Commission District Office, Rautahat decided to provide one bigha 10 kathas (one katha equals to 3645 sq.ft.) of land to Sumitra Devi Sapkota of the then Rangapur Village Development Committee-5, Rautahat on September 9, 2010. Similarly, the commission distributed 10 kathas of land to Panilal Chaudhary, and one bigha to Navaraj Khulal of the same village. In fact, none of them were landless squatters. Sumitra Sapkota owned three kathhas of land, including one katha plot no 334 (Gha), two kathas 5 (Ka) polt no. 333, and 5 (Ka) plot no. 349 in Rangapur VDC-5.

Likewise, Navaraj Khulal owned 9 kathas 13 dhurs (one dhur equals to 182.25 sq.ft.) of land. Even his father Krishna Bahadur Khatri had 7 kathas 13 dhurs of land, including 2 kathas of (Kha) plot no. 142 at Rangpur-5, and 7 kathaas 13 dhurs (plot no. 274, which included his residence) in the same ward. Similarly, Panilal Chaudhary, who got land in the name of landless squatter, too, had 13 kathaas 10 dhurs of land (plot no. 59) at the then Rangapur-7. This was revealed after a petition was filed at the Ministry of Land Reforms and Cooperatives when a piece of land belonging to local Shree Madhyamik Vidhylaya was registered in a person’s name, who claimed to be a squatter.

Bedhraj Sharma, Chairman of Bardiya Landless Squatters’ Problem Resolution Commission, formed to identify and address the problem in 1998, distributed several bighas of land to political cadres. Sharma, the then district president of Nepali Congress, registered one bigha each (plot no. 154, 155, and 156) of then Sanushree VDC to Tara Parajuli, his daughter, Bishnu Maya Bhusal, his daughter-in-law, and Dev Kala Adhikari. Details can be found at the district land survey department and land revenue office of Bardiya. None of them were squatters.

Bedhraj Sharma, Chairman of Bardiya Landless Squatters’ Problem Resolution Commission, formed to identify and address the problem in 1998, distributed several bighas of land to political cadres. Sharma, the then district president of Nepali Congress, registered one bigha each (plot no. 154, 155, and 156) of then Sanushree VDC to Tara Parajuli, his daughter, Bishnu Maya Bhusal, his daughter-in-law, and Dev Kala Adhikari. Details can be found at the district land survey department and land revenue office of Bardiya. None of them were squatters.

There are numerous instances of fraudulences. The commission formed to address the landless squatters’ problem registered a piece of land (five kathas, five dhurs of plot no. 141) at then Sonpur VDC-1 of Dang in the name of Makalu Chaudhary in 1996. Hari Prasad Chaudhary, the then Member of Parliament representing the then CPN-UML from constituency-1, influenced the commission to register the land in Makalu’s name. Bahidar Chaudhary, a UML cadre, of the same place, too, received one-and-a-half bighas of land (plot no. 273) in 1994. None of then were landless.

The commission formed by then UML government under the chairmanship of Rishi Raj Lumsali in 1994 was the commission to distribute the most bighas of land. According to the report made public by the Lumsali-led commission, out of the 58, 340 families who received lands, 24,470 were squatters, 24,052 temporary settlers, 194 Kamaiyaas, and 3,302 families were victims of floods and landslides. However, details of the rest 6,321 families have not been disclosed, whom according to a retired government official at the Ministry of Land Reforms, are party cadres. However, Lumsali defends his decision saying that the decision to distribute the land was made based on consensus. “We distributed the lands on the basis of recommendation of the district commission, which included representatives of Nepali Congress, Forest Department, and Survey Department,” he clarified.

However, quite a lot of families, who obtained land certificates, have failed to get the land. For instance, Dhan Bahadur Lopchan of formerly Kamaiya-5 owned one bigha 7 kathas and 1 dhur of land until 2001. Later, he was given a plot of 14 kathas (9/Cha 103) at the then Jirayat in lieu of his land in the name of expanding community forest. He received the land registration certificate from the Commission. However, since the commission could not furnish the record, he was totally taken aback.

Similarly, in 1999, the Landless Squatters’ Problem Resolution Commission, Saptari handed over land ownership certificate of one bigha to Damodar Sadha and his four brothers of then Madhupatti, Saptari. However, the land certificate, too, lacked the record. Bilath Ram of Dolatpur-3, Saptari, who had received land ownership certificate of 8 kathas, too, had the same story.

Says Gopal Bahadur Tamang, central member of Land Reforms Forum, “Among those who contacted us, a total of 25 thousand families — deprived of land record — have not received land despite getting the certificates.” Tamang adds, “Lands were distributed based on nepotism. Those having no political connection were left out.”

Mansuram Chaudhary of Natri, Lamahi Municipality-1 has a land registration certificate, which shows he owns one bigha of land. However, the record at the Land Revenue and Management Office shows that the plot was a public land. The Forest Reinforcement Project had provided Chaurdhary with the land certificate in 1988.

Mohan Lal Chaudhary and Krishna Kumar Chaudhary share the same ordeal. Consider what Krishna Kumar has to say: “15 families residing in Nirti have been facing similar pain.” These families were once tenants of Prem Kumari Chaudhary, a landlord in the village, who send them away after rumors of fixing land ceiling spread like wildfire in 1961. Since then, they started residing in Nirti by felling down the trees.

Landless in misery, always

Nira Dhungel and Mina Mishra Upadhyaya of Khajura-3 of Banke, sold their land to Ramesh Thapa of Saigaun VDC-1 (formerly) of the same district triggering displacement of around 36 families residing in the land since 1981. So sooner had he purchased the land, Thapa started issuing stern warning to the settlers to leave the land straightaway enticing disputes. Local Udaya Raj Khatri, a local, says, “We have nowhere to go. There has to be some arrangements for us.”

(From L to R): Mahawati, Gita Devi and Kalawati Chamar at the squatters’ settlement at Chhirbiray, Golbazar Municipality-6, Siraha.

Five families of Pratap Kumar Gautam, Natayan Gautam, Kul Dev Gautam, and Chin Kumari Gautam have been residing in plot no. 155 and 156 of (formerly) Sonashree VDC ‘Gha’ since the expansion of Bardiya National Park in 1985. However, Dev Kala Adhikari, Tara Parajuli and Bishnu Maya Bhusal have been pressurizing the Gautam families to vacate the land within a month after the Bed Prasad Sharma-led Commission gave the land to them. The Gautam family then filed a case at the Bardiya District Court and the Nepalgunj Appelate Court demanding that land be registered in their names. “The court did not listen to our voices,” Gautam complained, adding, “We have nowhere to move from here. My family is shattered. I once thought of committing suicide but I remembered my responsibilities towards the family.”

There have been quite a lot of instances that the Commission favored people having political nexus. For instance, on December 24, 2010, the Commission District Working Committee led by Mansobha Pandey of Nawalparasi distributed land receipts of the then Tamsariya VDC to 352 families residing in a public land in Chormara, Nawalparasi. A case was filed at the Commission for the Invesitgation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) against the squatters’ commission for distributing some 12 bighas of public land arbitrarily in the name of landless squatters. The CIAA on December 23, 2012 directed the government to block all transactions, including land trade, and to return the land. Meanwhile, the squatters filed a case at the Supreme Court against the CIAA’s directives. The Court on August 24, 2017 dismissed the CIAA directives. Interestingly, the then Chief Justice Gopal Prasad Parajuli was accorded a warm welcome along with a mucial band by the locals of Chormara, when he was in the village in February 2017. A joint bench of Parajuli and judge Tej Bahadur KC had decided the case in favor of the locals.

Jagat Deuja, an expert in land ownership issues, says, “Those having political nexus or having influence get lands from the commissions. In fact, the genuine landless squatters are deprived of lands.”

Identifying landless squatters

At times, natural disasters displace people compelling them to become squatters. According to Home Ministry data, natural disasters claimed around 11 thousand 163 lives from 2011 to 2015 throughout the country. The number of families will not exceed 15 thousand even if the deceased are considered as landless squatters. The commissions formed by the government have been alleged of snowballing the number. A total of 396,344 families of 25 districts had on January 31, 2012 applied for recognition as landless squatters at the Bhakti Prasad Lamichhane-led commission. Likewise, the Sharada Prasad Subedi-led commission, which had issued a notice calling for applications on June 16, 2014, received applications from a total of 861,000 families for the same. The considerable increase in the number (by around six lakhs in just three years) of landless squatters seems unusual and strange.

Jagat Deuja labels the rise in the number of landless squatters as ‘unusual’ at a time when there has been no such natural disasters during the period. “The formation of such commissions has been basically aimed at distributing land to their near and dear ones. People who are genuinely landless are not benifitted,” he argued adding that the problem will not be addressed by calling for applications or by distributing lands. “The data has to be accumulated through a systematic process by collecting details from the wards and organizing public hearings,” he suggested. Deuja also said that the government needs to put a ban on land trading for a certain period of time for the purpose.

Objective: seizing of land

The trend of calling aplications will, and has invigorated those who have political connection rather than addressing the problems of genuine squatters. According to land rights activist Ganesh Biskwokarma, this has encouraged shrewd people to acquire fertile lands in the name of squatters. Take for instance: Yagya Bahadur Raut, who owns a house and land in Besisahar, Lamjung, has a house buolt on a piece of land at Dhaankhola of Chandrauta-Bhalubang stretch alongside the East-West Highway, as well. What is hopes now is the soon would-be-formed commission would ‘offer’ him land ownership certificate of the land at Dhaankhola where he has buikt a small house.

A house built near the Tinau River at Buddhanagar of Butwal. Photo courtesy: Mukesh Pokhrel

Likewise, Jivlal Biswokarma, who owns a three-storey house at Chandrauta, expects to acquire a land in the name of landless squatter. Raut, whom we met at his Dhaankhola-based house in April 2018, said, “There were only 25-30 houses here. The number has reached 100 now.” Isn’t this enough to understand the real scenario of how people ‘capture’ public land?

Mina Kumal’s family of Nawalparasi has been staying as squatters at the banks of Tinau River, Ranigunj of Motipur, Butwal, for the last 12 years. Prior this this, this family was residing in Dipnagar of Butwal as squatters. They moved to Ranigunj after selling the land that they acquired from the squatters’ commission in 1999. Consider what Mina has to say now: “Some political leaders have assured us that we will get a plot of land soon after the formation of another commission. We are waiting for it.” She is hopeful of getting one soon.

The tendency has been challenging now. This is the reason why members of a single family have occupied several pieces of land in the same area. Families of Pavi Pariyar and Thulu Maya Pariyar, who moved from Baletaksar of Gulmi, have occupied public lands in Ranigunj with the hope of getting them reistered in their names. Pavi has constructed a hut to settle her 66-year-old mother-in-law by occupying a piece of land nearby. “We, including my mother-in-law, are waiting to get the land ownership certificates. Leaders have assured us of providing land ownership certificates during the election campaign,” Pavi said.

Even the lands encroached upon but do not have land ownership certificates have been traded these days. Krishna Prasad Gaire, who came from Kaseni of Palpa, purchased a hut made of tin sheet on 5 dhoors of land at Rs 3 lakhs. “Now this land costs Rs. 10 lakhs,” he boasts.

Sumitra Sapkota of the then Rangapur VDC-5, Rautahat, sold one bigha 10 kathas of land to Sushil Baniya on Septmber 8, 2016. Panilal Chaudhary and Navaraj Khulal also sold their land received in the name of landless squatters to Shreehar Prasad Kalika, Munna Prasad Baniya and Sujan Kalika.

In Palpa, a total of 6 thousand 500 families, claiming to be landless squatters, had applied in 2013. Fifteen hundered of them had then constructed huts by encroaching public land. Says the then central president of landless squatters’ commission Gopal Mani Gautam, “The trend of acquiring land in the name of landless, selling them, and occupying another piece of land is increasing alarmingly.”

There are several squatters’ settlements, mostly in Terai, including Dipnagar, Saljhandi, and Devdaha Shitalnagar in Rupandehi, Dumkibas in Nawalparasi, Gorusinghe of Kapilvastu, Bhalubang of Dang, Churimai of Makawanpur, Pathlaiya of Bara, Katahari of Morang, and Bhokraha of Sunsari. According to Forest Survey Report 2016, more than 1,800 hectares of land get encroached in an average every year.

‘Land is not the solution’

The governments have turned such commissions as a body for making political appointments by entrusting party cadres, who lack general knowledge on the issue for the task. The interim government led by Krishna Prasad Bhattarai formed a commission led by Housing and Physical Planning Minister, Bal Bhadur Rai in 1990. Likewise, Girija Prasad Koirala-led government formed a nine-member commission led by Shailejha Acharya in 1991. The then CPN-UML-led government formed another commission led by Rishi Raj Lumsali in 1994.

Squatters’ settlement at Naraha village municipality of Siraha.

Soon after, the Sher Bahadur Deuba-led government formed a commission under the then Land Reforms Minister, Buddhi Man Tamang. In 1997, the Lokendra Bahadur Chand-led government formed a commission under Chanda Shah. In 1999, Surya Bahadur-led government formed a commission under Buddhi Man Tamang. After this, Gangadhar Lamsal, Siddharaj Ojha, and Mohammad Aftab Alam led the commission from November 24, 1999 to 2000.

Formation of such commissions did not end here. Several commissions were formed after the Peoples’ Movement of 2006. In 2009, the commission was led by Gopal Mani Gautam, Bhakti Prasad Lamichhane in 2011, and Sharada Prasad Subedi in 2014.

The Lumsali Commission distributed the maximum land accounting more than 21,974 bighas. Mohammad Aftab distributed 9,453 bighas followed by Tarini Dutta Chataut, who distributed 7,036 bighas. Likewise, Gopal Mani Gautam distributed 4,853 bighas of land. Joint Secretary at the Land Reforms Ministry, Gopal Giri says the data of the commissions has not been up-to-date and managed. “It’s difficult to find the record of the commissions.”

Meanwhile, the government on March 2, 2017 formed a ‘Well Managed Housing Commission’ to check the rampant encroachment of public and Guthi land, and to address the squatters’ problems. The Commission headed by Gopal Dahit included Khagendra Basnyat, Prem Singh Bohara, and Jitendra Bohara as expert members, all former Maoist cadres.

According to Land Reforms Management Ministry, the Chairman of the Commission gets salary and other facilities at par with state minister while the members get salary and facilities at par with government secretaries. The commissions are formed in the districts as well. The Chairman of the district commission enjoyed the salary and perks at par with a joint secretary. In fact, the main objective of forming district-level commissions is to engage party cadres.

The political parties are aware of the fact that such commissions cannot address the squatter’s problems. Thy, in fact, paly this card during election campaigneering. Lumsali, too, is apprehensive that such commissions would address the squatters’ problem. “Merely distributing land will not address the problem. The problem has something to do with employment. Employed people do not have time to stand in a queue of landless squatters,” he said adding that the government lacks actual data about the number of genuine landless squatters in the country.

The recently formed well managed housing commission was expanded to the district level as well. However, Land Management Minister Chakrapani Khanal anulled the commission on April 27, 2018 alleging the officials of working for financial benefits. However, the incumbent Land Management Minister Padma Aryal is in faor of forming another commission, which is evident that ministers, too, are involved in emptying the state coffer.