Former Maoist combatants waged the 10-year insurgency against ‘feudal’ creditors. Now the same creditors are evicting them from their own village.

Lokendra Bishwakarma |CIJ, Nepal

It takes around three hours to reach the Jagatipur Durbar that today lies in ruin from Khalanga, Jajarkot’s district headquarter. The palace was built in 1455 by Jagati Singh, the founder of the Jajarkot state, during the period of baise-chaubise states before Nepal’s unification. To reach there, one needs to trek uphill across the place called Bohara. The mid-hill highway cuts right through Jagatipur’s front yard.

Katigaun, which falls in the then Jagatipur VDC-3 and now Bheri Municipality-11, is known as ‘comrade gaun’—comrade village—these days. During the ten-year Maoist insurgency, this village protected those with red bands on their heads and supported the insurgency. But these days, Katigaun is mired in social violence, poverty and deprivation.

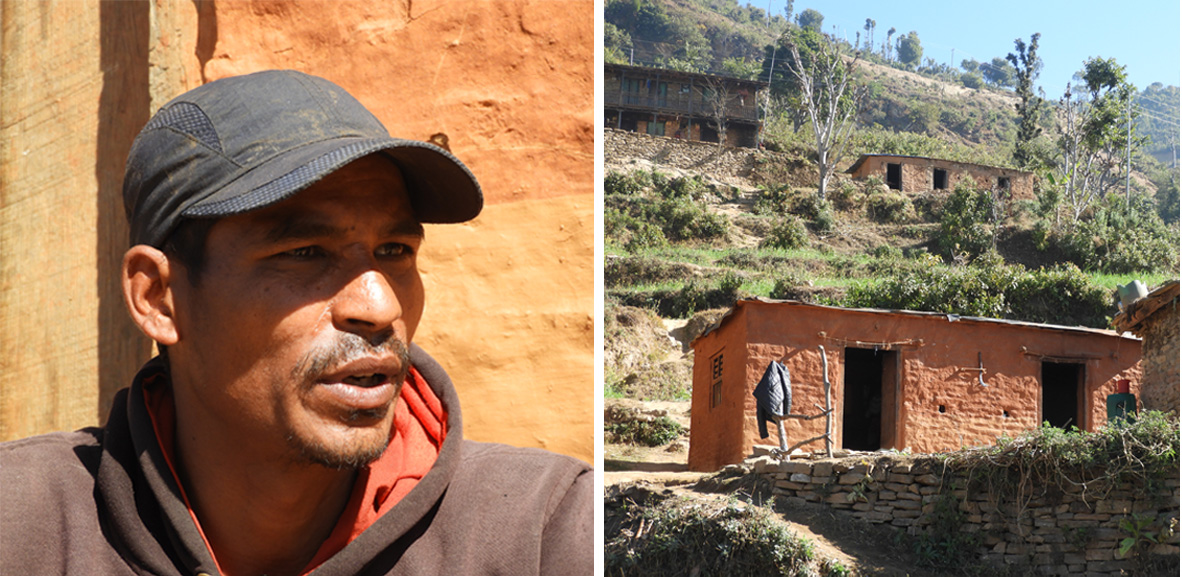

Birman BK and his house (right) seized by moneylender due to his inability to pay debt. Photo: Lokendra Vishwokarma

Birman BK, who is 32, has gone from a herdsman to a Maoist insurgent to a ‘kalipare’, a worker in foreign employment. It was around 1997 that Maoists taught mountain climbing to those who tended to cattle and carrying rifles to those doing household chores. The insurgency that started in 1996 was reaching its crescendo. It was around that time that Birman felt that he’d rather be a ‘comrade’ than a herdsman. So Birman fought the battle with his nom de guerre ‘Prakash’. The insurgency did bring about a change in the political system but neither could he save his house nor his fields. He was evicted by those against whom he had waged the war.

After Birman started fighting the war, his family struggled to even make their ends meet. They bought essentials from a local grocery on credit. By the end of the war, Birman had to pay Rs21,000 on loan. The family was swindled too, as the groceries sold a sack of rice with marked price of Rs1800 at Rs2900. “There was a risk that if you ask the price, they wouldn’t sell it to you at all,” Birman says. “I needed to feed my family by any means.”

A majority of Katigaun’s residents have the same routine as Birman’s. For them, the money earned during six month stay in India is only enough to pay back the creditors. Birman himself couldn’t break this practice, and today, he has a loan of Rs68,000. “There was loan previously too and when I wanted to build a house, I took some extra loan,” he says. Little did he know that the loan would trouble him deeply.

He provided the authority to calculate the interest on Rs89,000 loan to his creditor himself. No document was signed between them. But Birman was clear that he needed to pay it back. Amid this, he went to India four/five times. But he couldn’t earn much and could only pay Rs40,000 to his creditor.

After failing to pay it back, Birman’s family felt uncomfortable to appear before the creditor and they stopped going to borrow daily essentials. Then the creditor began to suspect them. “I expected to earn enough to pay back the loan but now I struggled to even provide for my family,” Birman reflects.

Around 2070BS, Katigaun’s youths had already sought alternatives to India in the gulf. Birman too got excited to go to Malaysia. After his relationship with the old creditor grew cold, he took out a loan from a new creditor, one Shashi Bharati from India. He took Rs30,000 from Shashi and some extra amount from his relatives and went to Kathmandu. The agent there managed the procedures.

Birman flew to Malaysia on Asar 6, 2071 with dreams aplenty. But his Malaysia stay didn’t turn out as he had expected. He fell sick while he was working and he couldn’t save much. Still, he paid back the loan he had taken to come to Malaysia. His old creditor said that the money he’d paid back was not enough. Birman grew anxious.

Motiram Luhar has relocated to India as a moneylender has seized the farm. His abandoned home is left in ruins.

After a three-year stay in Malaysia, Birman returned back to Nepal and then again went to India, this time along with his family. He would earn Rs400 for daily labor and this would not be enough to treat his wife and provide for the family. Back home, his creditor Yadu Prasad Acharya would threaten him to seize his land if he didn’t pay back the loan. Acharya said Birman had Rs700,000 more to pay while his son had said Rs500,000. After failing to pay it back, the creditor seized Birman’s land in Petaripata and house in Barpani, Birman says.

The land of Birman’s siblings was in the name of their father Sarki Barkami. The creditor took away two patches among the land, Petaripata’s kitta number 384 and kitta number 74, after he failed to pay back Rs700,000. The creditor informed him of his decision on the phone. Finally, on Mangsir 4, 2075, Birman was officially homeless.

Naresh, the creditor’s eldest son, says that his father had built the home for Birman and had even told him he’d waive the interest if he went to India and earned some money. But of the Rs700,000 credit, the land fulfills only Rs400,000, Naresh claims, adding that they sold the house at Rs125,000 and the land at Rs275,000 and hence incurred loss.

Since he had no home anymore, when he returned back, Birman stayed at his in-law’s house. After that, his brother Padambahadur took back the home the creditor had seized, promising him to pay Rs125,000. According to Birman, the house is dilapidated now, it is of no use in rain or cold.

One Birman wondered how the creditor sold his land and house at Rs400,000 in exchange for Rs700,000 loan he had taken. He asked the local leaders to calculate.

When the local leaders calculated the price, it turned out Acharya had made Rs125,000 more than Rs700,000 but Birman hasn’t yet received the extra amount. “If this tendency flourishes further, the whole village will be gobbled up by creditors,” says Prem Shahi, local leader of Nepal Students Association. “Everybody will be evicted.”

Homeless Birman said with a sigh, “The very people that we termed feudals and rebelled against are now gobbling up our properties.” Birman added that he regrets he took up the guns.

Birman, who lived in India’s Garhwal in Uttarakhand state, now lives along the Mid-hill highway and provides for his family by labor work. “It’s hard to live now,” he says.

Homeless, penniless

Dharma Barkami has a similar story to tell as Birman’s. His family was with the Maoists during the conflict. After the peace accord, he spent a long time in India. After he returned back in 2070, he conceived a plan to fly abroad and asked his father, Aaite, to take some loans. His father reached out to the same creditor as Birman, Yadu Prasad Acharya.

Dharma’s family too had some credits to clear for the groceries. Aaite took Rs105,000 from Yadu and sent his son for foreign employment. But Dharma fell sick and returned within 15 days after he landed in Malaysia. Back home, Yadu began to ask for land since they couldn’t clear the loan. Then Aaite says that he passed the land at Muchhain and Pyani to Naresh’s name. “He took me to Khalanga on his bike and made me pass the land,” Aaite says.

Soon Dharma began to suffer from mental illnesses. He was taken to India for treatment, says Hira, Dharma’s wife. They returned during Dashain of 2079BS and are now taking shelter at his brother’s house. Dharma and his 17-year-old son are still in India.

A fighter in the hut

Kalpana Chalaune went underground around 2057BS when she was all of 14. At 18, she became a platoon commandor and then got married to Jeetbahadur BK—a ‘janabadi’ marriage. Little did she think then that her husband would have to go to the gulf and then India to make a living.

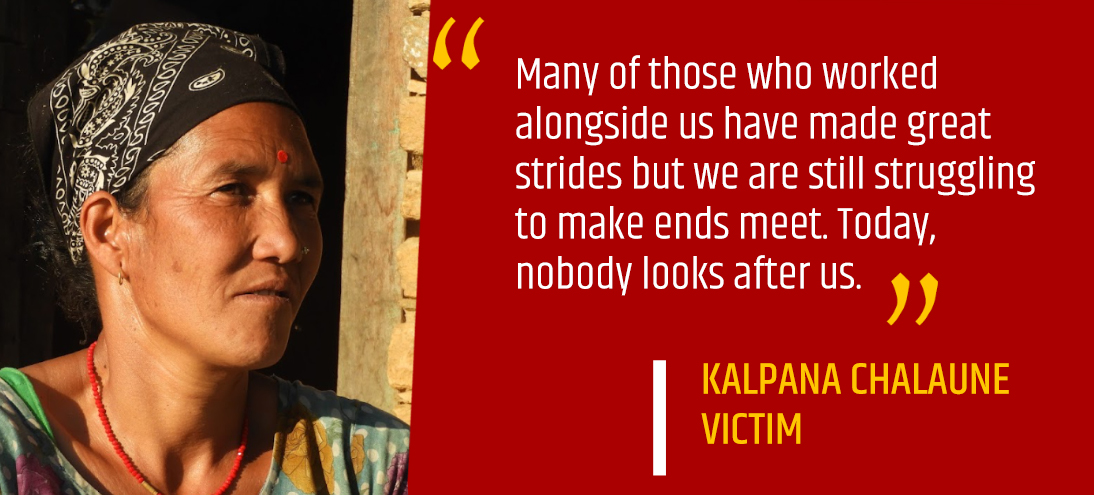

“After the regime change, we dreamed of building a house and giving children a good education,” Kalpana recalls. “Many of those who worked alongside us have made great strides but we are still struggling to make ends meet.” Because she got married to a Dalit man, Kalpana didn’t get any support from her maternal side and her in-laws.

The house of Kalpana Chalaune and Jit Bahadur Bk. During the Maoist insurgency, they were ‘platoon commander’ and ‘company commander’ respectively.

Fifty-five-year-old Jeetbahadur flew to the gulf in the end of 2070BS. It was also Yadu who provided him a loan of Rs100,000. After Jeetbahadur sent home money, Kalpana paid Yadu Rs150,000 including interest but the creditor still nags them saying the loan is not fully paid yet. Jeetbahadur is in India’s Garhwal now. Kalpana lives in the village with two sons. “We toiled hard for ten years during the war,” she says. “Today, nobody looks after us.”

Katigaun today is mired in poverty, deprivation, illiteracy, caste discrimination, and loans. This has robbed the whole village of its vitality. The village’s name ‘Comrade Gaun’ stands as a stark irony. The former Maoist combatants are receiving the short end of the stick from the creditors who they once railed against. And the creditors are humiliating them on the back of Maoist leaders themselves.

Competition among creditors

Katigaun is home to 170 Dalit households. Of them, 80 are mired in debt and 12 have already had their properties seized by creditors. There are only two creditors—Yadu and Hari Prasad Sharma. To understand how they are dominating an entire village, one has to return to wartime.

While Jajarkot was the base area of Maoists around 2053BS, Jagatipur was yet to be declared the ‘lal-killa’, meaning prime base. That same year, Yaduprasad Acharya, son of former pradhan pancha Gopalprasad, started his grocery store in Jagatipur. Yaduprasad was an experienced businessman having done business in Khalanga and Surkhet already.

Katigaon, Jajarkot. 80 families from this village are caught in a cycle of unrepayable loans from moneylenders.

There were no competitors to his business until 2055BS. Yadu’s store had come as a relief to the villagers. Seeing Yadu’s success, his uncle Hariprasad opened a rival shop. Hariprasad was a permanent teacher at the local Shiva Shankar Secondary School. Their competition got so intense that they began to bribe customers. So much so that Hariprasad would promise to pay the loan taken by his customers from Yadu if they promised to buy supplies from his shop. Yadu would also do likewise. Since they provided goods on credit, their business proliferated by the day.

Majority of young men from Katigaun go to India for six months. Their families buy supplies from Yadu and Hari’s shops on credit. After they return, they pay back the credit. But the loan keeps on adding up. Yaduprasad says, “I think I have to receive 2-4 crores. I have given the responsibility to collect it to my son.” Yadu’s son Naresh showed a list of debtors that had to collectively pay him Rs6 crore 4 lakhs 84 thousand and 791, over Rs60 million. According to Naresh, among those who have paid back their loans with their lands are Birman BK, Dharma BK, Nanda Bahadur BK, Amrit BK, Bhakta Bahadur BK, Baishake BK, Kamal BK and Megal BK. Thirty-nine more are yet to pay their loans back. Among Yadu’s two sons, the elder Naresh is a contractor and the younger Tilak is a local leader. Naresh is operator of YK Construction and Tilak is the secretary of Nepali Congress Jajarkot (b). Yadu’s elder brother Bhimprasad is close to the CPN (Maoist).

Access to power

Hariprasad is the second eldest brother of Gyaniprasad Sharma. Gyani is a member of Maoist Centre’s Jajarkot district committee. Gyani, who has already served as deputy chief of district coordination, has access to high echelons of power. Hari is not just protected by Gyani, but also by Mayaprasad Sharma, the National Assembly member who is Hari’s friend since childhood.

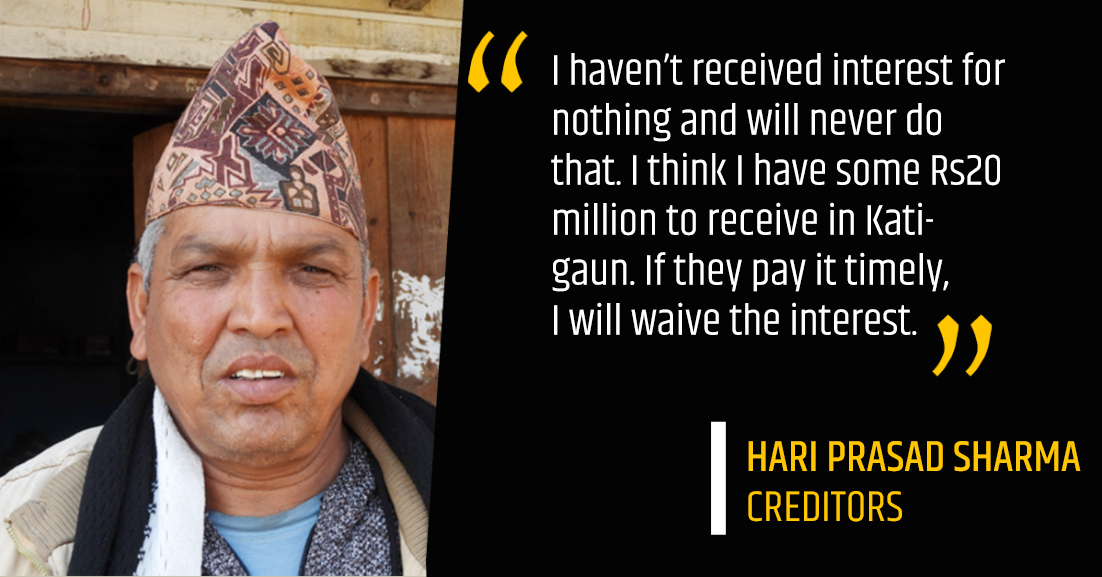

“I haven’t received interest for nothing and will never do that,” says Hariprasad. “I think I have some Rs20 million to receive in Katigaun. If they pay it timely, I will waive the interest.”

Hariprasad has more debtors in Katigaun than Yadu. Hariprasad admitted that 53 families in Katigaun are his debtors and he has received land from six families—that of Kalo Chanara, Bhakta Bahadur Barakami, Hemanta Luhar, Harke Luhar, Chitra Bahadur Luhar, Goblo Luar and Motiram Luhar. He says, “Hemanta has yet to pass the land while Motiram has yet to pay Rs398000.”

Ramlal Acharya, principal of Shiva Shankar Secondary, says that the parasitic creditors of Katigaun are giving residents a hard time. “What could a mere teacher do against the atrocities of powerful creditors!” he said.

In the fiscal year 2078-79, a plan under the ‘high hill and mountain area prosperity program’ was introduced to develop Katigaun into a model settlement.

On Jestha 26, 2079, the executive meeting of Bheri Municipality formed a five-member committee in presence of ward chairs and engineers. Laxmi Prasad Jaishi, who was appointed ward chair under a Congress ticket, was named the committee’s coordinator. On Asar 9, 2079, the committee selected 50 households. But the ward chair revoked the program after his cadres weren’t included as part of the 50 households. That same day, he submitted a letter to the municipality to stop the program. The committee decided on the 50 households in the evening, the same the coordinator wrote the letter. The municipality then retrieved the program. After that, there’s not a single awareness or development program that has happened in Katigaun.

In the village’s Syalapani tol, a temple is being built with a Rs2.5 million budget. But there’s no program conducted for the village’s social and economic development. The local unit has prioritized temples, but there’s no attention to the increasing poverty, deprivation, caste-based discrimination and illiteracy. Only two persons have so far completed their higher secondary education in Katigaun, a Dalit settlement. Meanwhile, the practice of child marriage is pervasive.

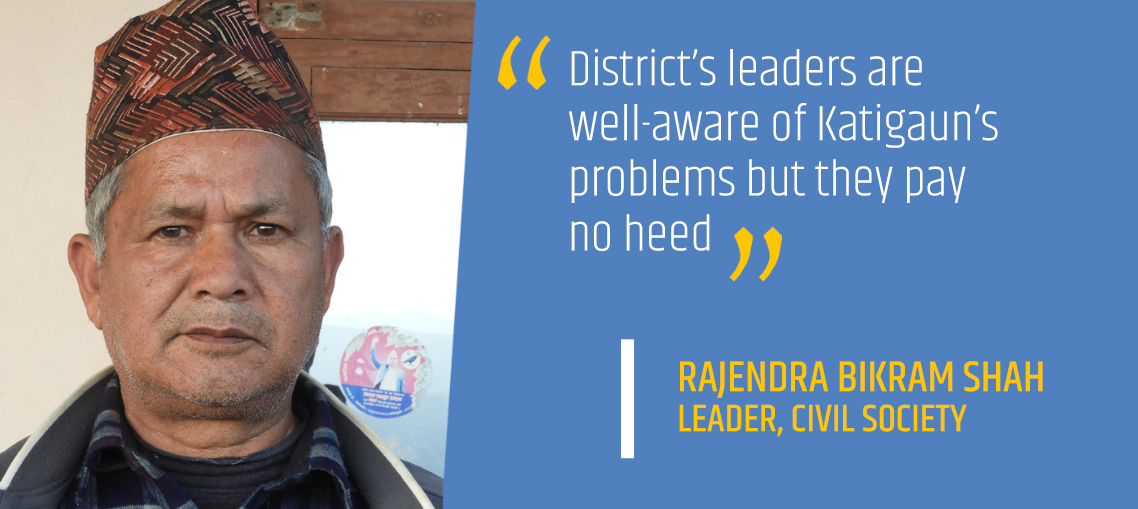

District’s leaders are well-aware of Katigaun’s problems but they pay no heed, says Rajendra Bikram Shah, a civil society leader. He points out a need for productive plans for the village’s development. He suggests that the local units provide grants for agriculture and other sectors. He also sees a need to launch a counseling service to bring back the village’s lost confidence.

In Katigaun, people are dejected and the creditors are holding sway. Whenever a new person arrives in the village, the residents plead, “Please don’t tell anything to the creditors. Otherwise one might have to move India, submitting land and house to the creditors.”