Finland has become an attractive destination for employment and studies for Nepalis three decades after the first Nepali restaurant opened its doors in the Nordic country. However, people who spend a large amount of money in the hope of landing a well-paying job without knowing the language and acquiring necessary skills face exploitation.

Ramu Sapkota |CIJ, Nepal

Chandrakot-8, Majuwa in Gulmi is home to around 100 households. A three-storied house in the middle of the town, belongs to 54-year-old Kunti Kauchha, who runs a hotel. Kauchha recently replaced her house built with mud with a concrete one after her eldest son Sanju went to Finland and sent money to pay for the construction.

Until three years ago, she lived in a house made with mud with her youngest son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren and ran an eatery there.

“It cost Rs 13.5 million to build this house,” said Kauchha standing in front of the new house. “All the money spent was sent by my eldest son. We can’t even imagine building a house like this with the earnings here !”

Sanju’s mother Kunti. Photos: Elina Laiho

Sanju Kauchha, who went to Finland on a student visa in 2008, now lives in the capital Helsinki. He is also the vice-president of ‘Finnish Nepalese Society’ .

Finland doesn’t see the sun for most of the year and the climate is much colder than Nepal. Despite the harsh weather, Finland has become an attractive foreign employment destination for Nepalis because of its social security system and the prospect of good earnings, said Kauchha.

“Finland has attracted many Nepalis like me as the husband also gets a leave from work when the wife is pregnant and they provide free healthcare and other facilities.” He said, “After coming to Finland, it’s easy to call your family members as your dependents.”

Parvati Aryal lives with her husband, daughter, eldest daughter-in-law and granddaughter in Chandrakot-8, Turang, 500 meters north of Majuwa. The eldest of her three sons lives in Qatar, the second is in Finland and the youngest in Kathmandu with his family.

The Aryal couple is also preparing to demolish their old house and build a new one after the second son Gokarna sends money from Finland. “It’s been six years since Gokarna went there,” Parvati Aryal says, “Before that he suffered a lot in India and Dubai. ”

Gokarna, who studied up to class 10, initially went to India and then to Dubai for employment. On the advice of an uncle living in Finland, he filled out the online visa application form from Dubai.

A year after applying, he was called to the Finnish Embassy in Kathmandu for an interview. He received his visa after two days. After that, he hastily came to Turang to meet his parents and flew to Finland from Kathmandu. Gokarna Aryal now works as a housekeeper in a Swedish company in Helsinki.

“In India the income was not that good, and in Dubai it was Rs 50,000 per month,” Aryal, who came home to Turang in April on leave, said. “Now I earn about Rs 200,000 per month. What I like best about Finland is the multicultural environment and that people don’t discriminate against us for being poor or foreign.”

He said that he soon plans to take his wife and daughter to Finland on a dependent visa. After landing in Finland, his wife will first enroll in language classes. “After learning the language, it isn’t difficult to land a job according to your skills and interests,” said Aryal.

Working without a permit

Nepal and Finland established diplomatic relations between Nepal and Finland in 1974. It was in 1983 that the Finnish government started working in the field of drinking water and education in Nepal. Around 18 years after the establishment of diplomatic relations, Finnish government established an embassy in Kathmandu in 1992. A year after that, in 1993, Devi Dutt Sharma from Gulmi opened the first Nepali restaurant, ‘Himalaya’, in Helsinki.

Nepal and Finland established diplomatic relations between Nepal and Finland in 1974. It was in 1983 that the Finnish government started working in the field of drinking water and education in Nepal. Around 18 years after the establishment of diplomatic relations, Finnish government established an embassy in Kathmandu in 1992. A year after that, in 1993, Devi Dutt Sharma from Gulmi opened the first Nepali restaurant, ‘Himalaya’, in Helsinki.

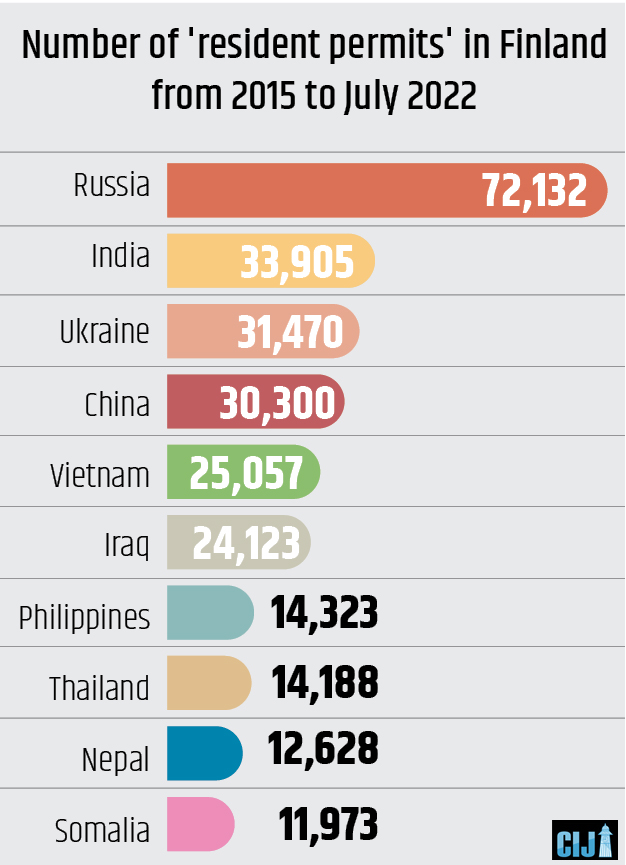

In the 1990s, Nepali started going to Finland for employment. According to the Finnish Immigration Service, the number of Nepalis who have obtained Finnish resident permit has reached 12,628. Most of them went to Finland on a student visa and started working there.

The two countries, however, have not yet signed a labour agreement. Dambar Bahadur Sunuwar, director of the Rescue and Relief Coordination section of the Foreign Employment Department, says that a labour permit is mandatory to go to work in any country regardless of the status of bilateral labour agreements. Nepalis who went to Finland to work haven’t taken such approval.

Sanju Kauchha, vice-president of the Finnish Nepali Society, said that since Nepalis are heading to Finland on residence permits, they don’t have to obtain a work permit from the Foreign Employment Department. According to him, if you stay in Finland for more than 90 days to work or study, you should apply for a resident permit.

Networks of relatives and neighbours

According to Kauchha, Nepalis who went to India to work initially came to know about Finland in Europe as a good destination to live and work. Then they invited their family members, relatives , neighbours and friends to come over.

Kauchha said that about 150 former students from his school Polaris English School, Majuwa, are now working or studying in Helsinki and other cities. “Most of the Nepalis living in Finland are from Gulmi,” he said.

Sagar Aryal of Turang, who went to Finland 10 years ago with the help of Kauchha, also took his father to Finland for permanent residence and his uncle’s son Gokarna Aryal to Finland for work. With his help, two other students from Turang are preparing to go to Finland soon.

The first generation of Nepali immigrants who went to Finland from 1980 to 2000 are now settled. Some of the 100 or so Nepalis who went to Finland during that period made great progress in the restaurant business.

A study report by the University of Helsinki (2018), mentions that Nepali people invite their family and community members to Finland, taking advantage of the legal provisions for family reunification and employment.

Between 2000 to 2007, a total of 3,485 Nepali workers landed in Finland on work visas.

According to a study report published in October 2020 about South Asian immigrants in European countries, after 2007-08 , the number of Nepalis going to Finland as students started to increase. Before that, there were many Nepalis who went as workers.

Mini Gulmi in Finland

Hemraj Sharma from Ampchaur is believed to be the first Nepali from Gulmi to land in Finland. After going there 35 years ago, he invited his family, and then his relatives Dilliraj and Ramprasad Aryal, over after five years.

According to Khageshwar Kharal of Ampchaur, Sharma, who was training as a chef in India, was taken to Finland by an Indian hotel owner. After accumulating some years of experience, he started his own business. Kharal says, “He took the workers needed from the restaurant from here. ”

Devi Dutt Sharma is also a first generation Nepali in Finland. He now owns eight restaurants in the country. Likewise, brothers Dilliraj and Ramprasad Aryal own four each. The brothers, who have their ancestral property in Ampchaur and a house in Kathmandu, have invested in hydropower projects, resorts and real estate in Nepal. With their help, a school and a hospital were built in Ampchaur.

Shankar Aryal with his wife and granddaughter, Gokarna Aryal with his family and Krishna Bhandari with his wife.

Every house in Ampchaur, Gulmi has on average one person in Finland. After Ampachaur, it’s the residents of Majuwa and Sota who are working as chefs in restaurants.

It’s been 10 years since Motilal Aryal of Ampchaur and his family went to Finland. According to Babu Shankar Aryal, following in the footsteps of his eldest son Motilal, his sister and son-in-law went to Finland. “Not only my children, three other family relatives are also in Finland,” said Shankar Aryal. “There are 15 others from the neighbourhood there.”

A University of Helsinki (2018) study report mentioned that most of the restaurant owners in Helsinki are from the Gulmi district of Nepal. Out of about 100 restaurants run by Nepalis, 50-60 are owned by people from Gulmi.

“During the late 90s, Nepalis were working in Finnish restaurants and most of them were from Gulmi district. “The study report says, although they didn’t have good work experience, they entered the restaurant business as they could understand the Finnish language.”

The report said that the restaurant owners bring workers from their own family and neighbourhood to work in the restaurant and form new circles.

There are 5012 Nepali residing in Finland. Although it is not certain about the number of people from Gulmi in Finland, Navin Bhattarai, president of the Finnish Nepalese Society, estimates the number to be around 50 percent among the total number of Nepali with most of them being on student visas. Just between January to July 2022, 36 people from Gulmi landed in Finland for study and work.

People from Gulmi have made a good name in the restaurant business. Hemraj Sharma, Devi Dutt Sharma and Ram Prasad Aryal of Ampchaur played a major role in establishing the Non-Resident Nepali Association and Finnish Nepalese Society . Established in 2005, the Finnish Nepalese Society has been supporting Nepalis suffering abroad and donating money for hospitals and schools in Gulmi.

Easy to get student visa

According to the Finnish government data, around 300 Nepali origin students have been admitted to Finnish schools every year since 2010. Between 2010 and 2020, 4,500 Nepali students were admitted to schools and universities. According to the data, 429 Nepalis were admitted for study in 2012 and 402 in 2017.

After Russia and Vietnam, Nepalis top the charts when it comes to the number of foreign students from Asia in the last 10 years. In 2010, only 156 Nepalis were enrolled in educational institutions in Finland, in 2016 this number increased to 309 and in 2020 it reached 396.

According to the National Agency for Education of Finland (2018), in 2017, there were 1,110 Nepali students enrolled in the bachelor’s and master’s degrees of commerce, administration, law, engineering and information technology in the universities and colleges there. This number is the fourth largest after Russians, Vietnamese and the Chinese.

The number of Nepalis applying for applied science studies in Finnish universities is more than Bangladeshis, Nigerians , Russians and Vietnamese. According to Finnish government data, 26 percent of the 1,031 Nepalis who applied to study applied science in 2018 were admitted.

Revised policy to attract students

According to Avinash Dhital, an expert in the ‘Capacity Building in International Higher Education Collaboration Project’ of Aalto University in Espoo, Finland, the Finnish government first targeted foreign students by providing them category ‘B’ visas. Category’ A’ visas were given only to workers. But now, students are also getting ‘A’ visas.

Similarly, students are allowed to work in Finland for as many years as they have invested in studying. Part-time working hours have also been increased from 25 to 30 hours per week. Category ‘A’ students can apply for permanent residence after four years and citizenship after five years.

“Workers who have a full-time work visa can work for 37 and a half hours a week,” says Dhital, who has been in Finland for the past 12 years.

The active age population in Finland is decreasing. Therefore , Dhital says that the government has made it easy for migrant workers to get permanent residence permits.

The ‘Talent Boost Program’ was launched in 2017 to attract foreign students and researchers to labour shortage areas. For this, the government has adopted various measures to facilitate foreigners in the education and labor sectors.

A press release from the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment on January 6 states that labour shortage in Finland has slowed down the development of various sectors, so job-based immigration has to be facilitated. Six months after that, family members of experts and entrepreneurial immigrants are being allowed permanent residence through a fast-track mechanism.

“The government provides immigrants all facilities that Finnish citizens get, from health and education to unemployment benefits, as soon as they change from a student to a worker visa, ” says Dhital.

Free vocational course

In Finland, until 2017, higher education in applied sciences was completely free for foreign students. Until 2008, a student could get a visa in Finland only by submitting their standardised English tests such as IELTS or TOEFL. They also didn’t have to present a bank guarantee. During that period, many Nepali students went to Finland to study applied sciences.

In 2017, after the provision of fees for applied science studies, Nepali students started going to Finland for vocational training courses that run for two and a half to three years. Vocational courses train applicants to work as cooks and waiters and even mechanical engineers.

Chandrakot Rural Municipality-8, Majuwa

Those who have completed 12th standard in Nepal are considered eligible for vocational courses. After completing a diploma in any vocational course, one can easily get a job. However , the Nepal government doesn’t officially issue a ‘no objection letter ‘ for vocational courses. But students seem to have found a work around to that as well.

Even if they go on a student visa, most of them aim to stay in Finland for a long time and earn money. Rameshwar Nepal, South Asia Director of Nepal-based Equidem Research, which is active in the field of labour rights, says that everyone wants to earn money for the financial security of families back home.

Labour exploitation and human trafficking

Those that initially went to Finland from Gulmi started opening restaurants and invited their relatives and neighbors over to work.

But soon accusations of labour exploitation were also made. Allegations against Hemraj Sharma and Devi Dutt Sharma’s restaurants led to a government investigation in Finland.

The Nepali Times (January 20, 2019) even published a report stating that a Nepali woman filed a complaint stating that she wasn’t paid her fair wage and was made to work for 24 hours at a private home and at a restaurant. She also said she faced sexual exploitation.

The report mentions that the problem arose as Nepalis who go to work in restaurants in Finland go there based on personal relationships. It is for this reason that they have to follow the will of the restaurant owner rather than the Finnish law.

It was reported that the restaurant owners opened accounts in two different banks in the name of the workers, took control of the ATM card of the salary account, and deposited a smaller amount in another account to pay them less than what the government rules state.

In 2019, Finnish police registered a case in the local court against the restaurant owners who were accused of exploiting Nepali workers.

Restaurant manager Devi Dutt and his wife Manju Sharma were also accused of human trafficking. The Finnish online newspaper Helsingin Sanomat published a report in March 2019 stating that Finnish police were investigating whether they had trafficked people or not. The Sharma couple confirmed that they are being investigated and told Sanomat that the allegations were baseless.

According to Helsingin Sanomat, police found that Nepali workers were being exploited in restaurants run or owned by Devi Dutt Sharma, Hemraj Sharma and Ram Prasad Aryal. It was mentioned that they called workers from Nepal and spent more time working in more than one restaurant than prescribed by the Finnish law.

Helsingin Sanomat wrote that Nepalis who come to work in restaurants in Finland were charged up to Rs 600,000, their passports were taken away, they were not given leave even when they were sick, and up to six people were confined in two rooms. They were found to be working more than 13 hours a day for a monthly wage of Rs 130,000.

When contacted by the Centre for Investigative Journalism, Hemraj Sharma, who is in Helsinki, said that he was not interested in talking about the issue.

As Finnish police informed CIJ via email, there are 20 cases of human trafficking and labour exploitation related to Nepali migrants being investigated since 2019. “Half of these incidents have been completed and reached the prosecutor,” the Finnish police officer said, “This year, we have started investigating four new cases.”

Regarding the investigation on Devi Dutt Sharma, police replied that they would not comment on an individual case. However, according to the information received from various sources, the investigation hasn’t been completed yet.

So, has the labour exploitation of Nepali workers stopped now ?

“No. Nepalis are more exploited in the first year they start working in restaurants here. A Helsinki-based researcher studying immigration told CIJ, “Everyone knows what’s going on, but no one wants to talk.”

The researcher, who does not want to be named, says that recently, Nepalis have started paying up to Rs 1 million to the restaurant owner or his agent to get a job in a restaurant in Finland.

According to Finland’s labour law, the first contract for a worker visa is for one year and it is then extended for four years. After completing one year, the employer can enter into another contract with the worker for another four years.

According to the researcher, Nepali restaurant owners take unfair advantage of this provision to exploit the workers who have not learned skills and are unaware of their rights for a year, and bring in new workers.

A study by the University of Helsinki points out that there are also unauthorized activities of the informal economy in the Nepali restaurant sector in Finland. It is mentioned in the report that immigrant entrepreneurs understate their income, pay low wages to workers and hide their real business to evade taxes.

They seem to be exploiting labour by appointing workers on the basis of verbal commitment. The 2018 report says that restaurant owners hire workers from the same community and caste to help each other to hide informal economic activities.

According to the report, salaries are not paid according to Finnish law. Employees are also made to work on holidays as well as Sundays without extra wages. Despite going through all these issues, they are forced to work in the same restaurant.

Navin Bhattarai, president of the Finnish Nepali Society, says that the service and facilities will be determined by the agreement between the restaurant owner and the workers. ” I don’t think this is a big issue , ” he says.

Consultancy business

Those who want to go to Finland for studies need to open an account on the website of the Finnish National Agency for Education. Then the university there conducts a written exam. After that, a group discussion and an exam is conducted. If a student passes both the tests, the student receives an online offer letter from the university, which should be sent by email to the Finnish Embassy in Kathmandu.

The embassy informs about the subsequent process through email. Based on that, students can upload documents to the Finnish government’s website. After the documents are in order, the embassy records biometric details and conducts an interview. After completing all the procedures, the status of the visa application is sent by email.

Students can go to Finland by completing the process online themselves, but if they rely on consultancies, they have to pay a fee. Meanwhile, the Finnish government’s immigration department has banned paid consulting services.

Rishabh Acharya from Biratnagar, who went to Finland after completing all visa procedures himself, says that Kathmandu-based consultancies are charging up to 100,000 rupees. According to him, they charge up to Rs 10,000 for creating an email address required to open an account on the website .

“They take the student’s passport and other personal documents,” Acharya, who is now in Finland, says. “After receiving the offer letter from the university, the consultancy also does the job of submitting the details on the website and charges up to Rs 100,000. ”

According to him, Baneshwor-based Rise Education Foundation, Epicenter Education Consultancy, Deep Blue Education Network Butwal and other consultancies actively send Nepali students to Finland. He said that vocational courses are offered free in Finland, but the consultancies charge up to Rs 300,000.

According to Acharya, the cost of health insurance to go to Finland is around Rs 30,000 to 32,000. A visa fee of Rs 50,000 has to be paid at the embassy, which is non-refundable. The insurance amount is refunded if the visa application is rejected.

“Applicants from consultancies pay an additional Rs 100,000,” Acharya says. “If the visa application is rejected, the consultancy doesn’t even refund that amount. ”

Sanju Kauchha says that now it is easier to go to Finland with a student visa than a work visa. A student, on an average, pays 2,000 to 3,000 euros for every academic semester in Finland. Those who want to study at a college in the capital Helsinki have to pay more than this.

When applying for a visa, students need to demonstrate that they have an amount equal to 7,000 euros in bank guarantee. “Earlier, you had to show your own real estate or property to obtain the bank guarantee,” Kauchha says. “Nowadays, the property of friends or relatives not related by blood can be used.”