Patients across Nepal suffer as public hospitals fail to employ super speciality doctors.

Sagar Budhathoki |CIJ, Nepal

There is hardly any vacancy for most specialised health care services in Nepal. This government policy means a severe lack of professionals trained in specialised health services. What’s more, those who have completed their education abroad and have come to Nepal to work end up going abroad again.

The Blood Bank is mandated to collect, process, store and distribute blood. However, the centre has failed to maintain minimum standards, leading to infection and other complications in patients.

One such victim was a teenager who underwent a blood transfusion on Asar 6, 2076, for Thalassemia, only to be infected with HIV. Experts say such incidents happen due to a lack of skilled professionals.

Meanwhile, Dr Bipin Nepal, the only blood specialist available in Nepal, works at a private hospital, Grande. “The health of many patients has been ruined because technicians who trained more than 20 years ago are still leading the field of blood. But the government still does not seem interested in reforming the system,” Dr. Nepal said.

Treatment underway in the Intensive Care Unit at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Maharajgunj

On Falgun 22, 2076, the then Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli underwent a second renal transplant procedure. At the time, the blood required for his treatment was sourced from Grande Hospital for quality assurance despite there being 117 public blood centres across the country.

The blood required for complicated surgeries at Human Organ Transplant Centre, Bhaktapur and Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH), Maharajgunj, is sourced from Grande Hospital because other blood centres cannot segregate elements such as platelets, plasma, and packed cell.

When Dr. Gyanendra Man Singh Karki, the president of Birat Medical College, was admitted to the TUTH due to Covid-19 complications, he underwent plasma therapy on Saun 10, 2077. Since no plasma therapy had been done in Nepal until then, the hospital requested Dr. Nepal for help. This explains how a doctor has to be invited from a private hospital as a public hospital does not have specialised doctors.

Dr. Bishesh Paudyal, a clinical haematologist, conducted the first bone marrow transplant in Nepal in 2012. While bone marrow transplant is possible in Nepal after that, Paudyal alone cannot handle a large number of cases. Despite this, Nepal’s only bone marrow transplant specialist is employed under a temporary contract.

According to Dr Paudyal, bone marrow transplant has remained out of bounds for many patients in Nepal as the government has failed to prepare enough human resources and infrastructure. “Patients have been dying undiagnosed as the government has failed to open vacancies for a sensitive issue like haematology. Meanwhile, doctors are discouraged from studying this subject,” he said.

Dr. Prabhat Adhikari, an infectious disease specialist who returned from the USA three years ago, completed a fellowship in internal medicine at the Inter-faith Medical Centre and infectious disease at the University of California. He also completed a fellowship in critical care at the University of Tennessee in Egypt. He worked at Grande Hospital for a while, but he is now unemployed.

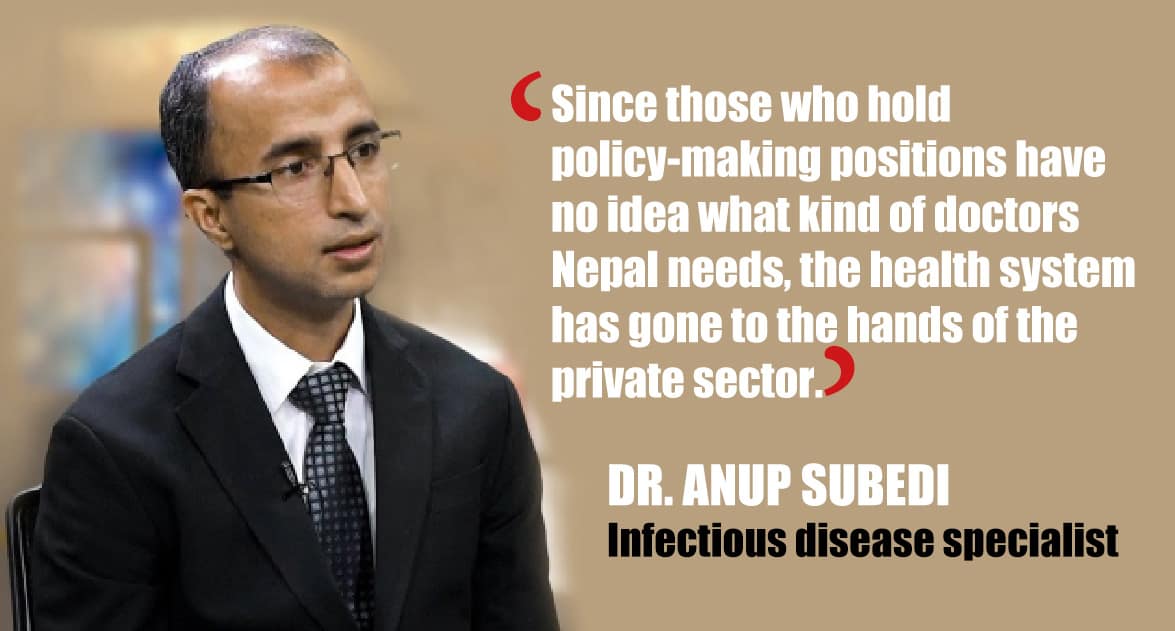

The story of Dr. Anup Subedee, an infectious disease specialist who came to the limelight during the Covid-19 pandemic, is no different. He wanted to work even under a temporary contract at the Shukraraj Tropical and Infectious Diseases Hospital, the Bir Hospital, or the TUTH. But he was not allowed to work at any of these institutions.

He said the administrators at the Ministry of Health and the institutions that teach medicine have no interest in producing a workforce, expanding services, and enhancing the quality of care.

Out of the only three infectious disease specialists available in Nepal, two are outside of the public health system. The third one has recently joined the Patan Institute of Health Sciences under a temporary contract.

During the pandemic, intensive care units in hospitals across the country faced a shortage of critical care physicians (intensivists). Health care professionals lamented that they had failed to save patients for a lack of an intensivist.

It is necessary to treat patients with organ failures under the care of an intensivist in Level-3 ICU. But there are just a few Level-3 ICUs and critical care physicians in Nepal.

On Magh 7, 2078, the Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal published a report on the effects of the government’s apathy towards critical care on the quality of care in Nepal.

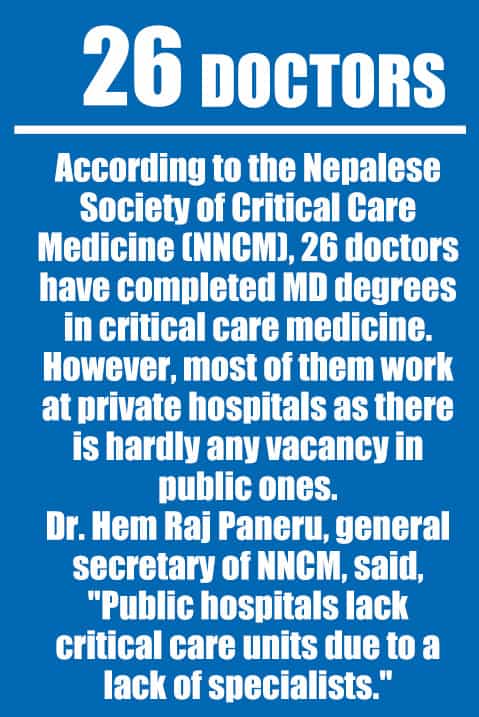

According to the Nepalese Society of Critical Care Medicine (NNCM), 26 doctors have completed MD degrees in critical care medicine. However, most of them work at private hospitals as there is hardly any vacancy in public ones.

Dr. Hem Raj Paneru, general secretary of NNCM, said, “Public hospitals lack critical care units due to a lack of specialists.”

Dr. Suvash Phunyal, who completed a DM degree in neuro-intervention from the All Indian Institute of Medical Sciences, said he has been working at a private hospital since he failed to get a position at a public one.

According to Dr. Phunyal, many citizens would get medical services cheaply if neuro-intervention services could be started at public hospitals. “Not everyone has access to private hospitals. But we can save many lives if we start this service at public hospitals.”

Dr. Dharmagat Bhattarai, who completed a DM degree in pediatric clinical immunology and rheumatology in 2019, said he has already diagnosed and treated ailments related to rheumatoid arthritis and immunology among children. He said that although many children suffer from these ailments, they fail to receive treatment. Employed at HAMS and Om hospitals at the moment, he tried to work at public hospitals even under a temporary contract without any success.

Dr. Biraj Nepal, who completed a DM degree in pediatric critical care from AIIMS in 2019, tried his best to find a job at a public hospital. However, hospitals such as Kanti Children’s Hospital, TUTH and Patan Hospital failed to hire him. Dr. Nepal now works at a private hospital.

Dr. Pushpa Raj Awasthi, who has also completed a DM degree in pediatric critical care, says he tried to explain to authorities at the Health Ministry and its various departments how vital his specialisation was for the country. However, they refused to listen to him. He now works at Seti Provincial Hospital in Dhangadhi under a temporary contract—at a hospital that lacks the infrastructure for pediatric critical care.

Dr. Ramesh Kandel completed an MD degree in geriatric medicine in 2015. When he returned to Nepal after completing his studies, he says, there was no geriatric specialist in any hospitals here. After remaining unemployed, Dr. Kandel was appointed under a contract at Patan Institute of Health Sciences.

Although he treated thousands of old-age patients at Patan Hospital, he could not secure a permanent job as a geriatric specialist, so he shifted to KIST hospital in Lalitpur and then to Rapti Institute of Health Sciences.

“The government has done injustice not only to specialists like us but also to old-age patients,” Dr. Kandel said.

In the year 2077, the Ministry of Health and Population prepared a guideline related to the operation of geriatric health care. The guideline mentions starting the services from 24 public hospitals.

As per the guideline, specialists in geriatric care will be appointed to provide health care to old-age citizens. However, out of the eight geriatric specialists registered in Nepal Medical Council, five have started working in India for a lack of opportunities in Nepal, their colleagues say.

Patients bear the brunt

If we are to scan the newspapers published between Saun 2077 and Baisakh 2079, a total of 14 patients have been kept captive for failing to clear the bills. In two of these cases, cadavers were kept captive, while one of the cases was related to suicide for failing to pay the hospital bills.

Such incidents show that even the people belonging to the middle-class lack access to care when it comes to complicated ailments, says Amod Pyakurel, a sociologist. According to Pyakurel, this is symptomatic of the problem arising from a lack of specialised services in public hospitals.

Ailments such as rheumatic arthritis and immunodeficiency afflict many Nepali children. However, there are only a few that get access to care. According to Dr. Bhattarai, the ailment in most such patients does not get diagnosed at all.

Ailments such as rheumatic arthritis and immunodeficiency afflict many Nepali children. However, there are only a few that get access to care. According to Dr. Bhattarai, the ailment in most such patients does not get diagnosed at all.

According to clinical haematologist Dr Bishesh Paudyal, four patients undergo bone marrow transplants every month at Civil Hospital, and there are 50 more patients awaiting transplants at any given time. A bone marrow transplant is a procedure to treat blood cancer patients who cannot be treated with chemotherapy. According to Dr. Sudhir Sapkota, specialist physician at Kanti Children’s Hospital, almost half of the cancer patients that visit Kanti are the ones suffering from blood cancer. There is no record of patients suffering from undiagnosed genetic ailments. According to Sapkota, the treatment of patients at the community level has been delayed due to a lack of specialists.

According to doctors working in the field, the number of blood cancer patients diagnosed in Nepal each year ranges between three and four thousand. However, there are only half a dozen specialist doctors; and all of them work in Kathmandu, and only two of them work at public hospitals.

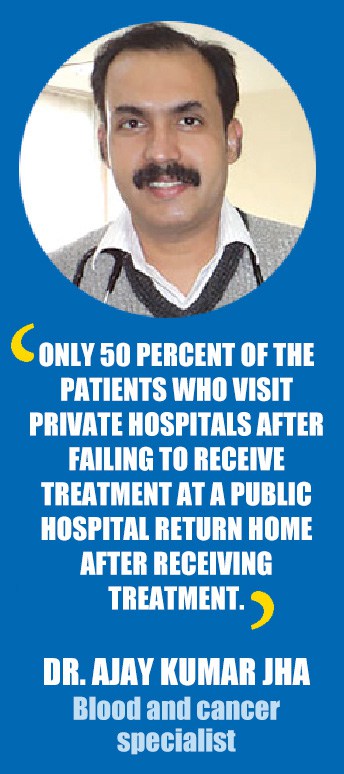

Blood and cancer specialist Dr. Ajay Kumar Jha says only a few patients in the community level suffering from cancer visit Kathmandu for treatment, and the downtrodden end up dying even as they await treatment.

According to Dr. Jha, only 50 percent of the patients who visit private hospitals after failing to receive treatment at a public hospital return home after receiving treatment.

According to a research monograph published by TIF Cyprus, there are around 800 thalassemia patients in Nepal. Each year, 327 patients are added to the list. According to a study published in 2077, almost 2 lakh individuals from the Tharu community suffer from sickle cell anaemia.

Almost 200 new patients reach Civil Hospital each year for a blood disorder. We can save up to 80 percent of the patients suffering from aplastic anaemia–the drying up of bone marrow. However, Dr. Paudyal of the Civil Hospital says ten such patients who reach there each week are sent home without treatment.

According to Dr. Paudyal, the lack of human resources means that only 1 percent of the total patients that require bone marrow transplants have received the services. “If the vacancies are not opened in public hospitals, we won’t even know about the thousands of patients who die due to a lack of treatment,” he said.

Brain haemorrhage is the biggest reason for disability in Nepal and the third biggest for death. Each week, an average of two patients go to other places from the Neuro Hospital in Bansbari for failing to bear the treatment expenses, Dr. Subash Phunyal said.

Although neuro-intervention technology is more accessible nowadays, Dr. Phunyal laments that he cannot provide the services to patients. It costs between Rs50,000 to Rs2 million for a treatment based on the neuro-intervention technology, but public hospitals can provide the same treatment at half that price, Dr. Phunyal said.

According to the World Health Organization, infectious diseases are detrimental to public health worldwide. The Covid-19 pandemic also showed a need to establish a super-speciality infectious diseases treatment centre in Nepal. However, the Health Ministry does not have the position of an infectious disease specialist.

Kanti Children’s Hospital refers an average of two to three patients to private hospitals for lack of beds. If the government wishes, it can create a group of pediatric critical care specialists and provide treatment to students in one go, says Dr. Nepal, a pediatric care specialist.

Dr. Nepal and Dr. Awasthi are the only two doctors registered in Nepal Medical Council to have completed DM degrees in pediatric critical care. According to Dr. Awasthi, it is sad that there are no positions for pediatric critical care specialists while children are dying for lack of such specialists. “The lack of critical care specialists and the required setup means many children are dying. This is a policy failure of the state,” Dr. Awasthi said.

State turns a blind eye

Although there is no specific data about the human and economic costs of the lack of specialist doctors in the public health care system in Nepal, this has had a long-term impact, says Dr. Senendra Uprety, a former secretary of the Ministry of Health. According to Dr. Uprety, many patients die due to this lacuna, no matter whether their ailments have been diagnosed or not.

For public health specialist Dr Baburam Marasini, the government cannot produce the required human resources in the absence of positions for specialised doctors. Moreover, even those who have studied abroad end up staying back, said Dr. Marasini. “It has already become difficult to handle the number of patients due to a lack of restructuring of the public health system.”

In addition to practicing medicine, a specialised doctor prepares human resources as well. However, due to the government’s policy, neither patients are getting treated nor new specialists are being prepared, says Dr Sharad Onta, a public health specialist.

In addition to practicing medicine, a specialised doctor prepares human resources as well. However, due to the government’s policy, neither patients are getting treated nor new specialists are being prepared, says Dr Sharad Onta, a public health specialist.

“If there is a specialist doctor in the public health system, they can contribute to the production of human resources and the formation of a system. But this is not happening at the moment,” Dr. Onta said.

Dr. Uprety, the former secretary, says the healthcare system is slipping out of the hands of the middle class. “The government should have produced specialised doctors on its own. But it has not even provided opportunities to those who have studied on their own. The healthcare system cannot improve in this way,” he said.

According to Dr. Kedar Baral, a public health specialist, the government should open new positions also to remove the unequal distribution of health services. “If we can place specialised doctors in all provinces, there won’t be the compulsion for patients to go to private hospitals or travel to Kathmandu,” said Dr. Baral.

Although the government has not opened positions, academic institutions such as the Patan Institute of Health Sciences, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Institute of Medical Education can hire specialist doctors on a contractual basis. However, most of the doctors who spoke with the Centre for Investigative Journalism say they failed to get a positive response even when they expressed their interest in working at those institutions.

While these institutions have hired many other doctors on a contractual basis, they have failed to hire specialists except for a few exceptions. The hospitals say they have not been able to hire specialist doctors due to a lack of the required infrastructure.

As the state fails to invest in specialised services, more than Rs200 billion is going out of the country, and almost 17 percent of the citizens have been pushed to poverty due to expenses on health, according to Nepal Health Account, 2017.

According to Dr. Anup Subedee, many specialist doctors who want to return to Nepal have not been able to do so as the state fails to provide them with opportunities. “As new diseases get diagnosed and the number of patients increases, the state should invest more in health. Any more delay will be too costly,” Dr. Subedee said.

According to Dr. Pravin Mishra, a former secretary at the Ministry of Health, it is necessary to increase positions given the ever-increasing population, the changing nature of diseases, and the changes in treatment technologies and methods.

A report published by the Centre for Investigative Journalism in 2020 showed that more than 50 percent of the doctors who studied under a government scholarship went abroad. One reason for the brain drain is the lack of opportunities here in Nepal. According to Dr. Subedee, doctors have failed to get opportunities since the government does not prioritise them.

“Since those who hold policy-making positions have no idea what kind of doctors Nepal needs, the health system has gone to the hands of the private sector,” Dr. Subedee said.

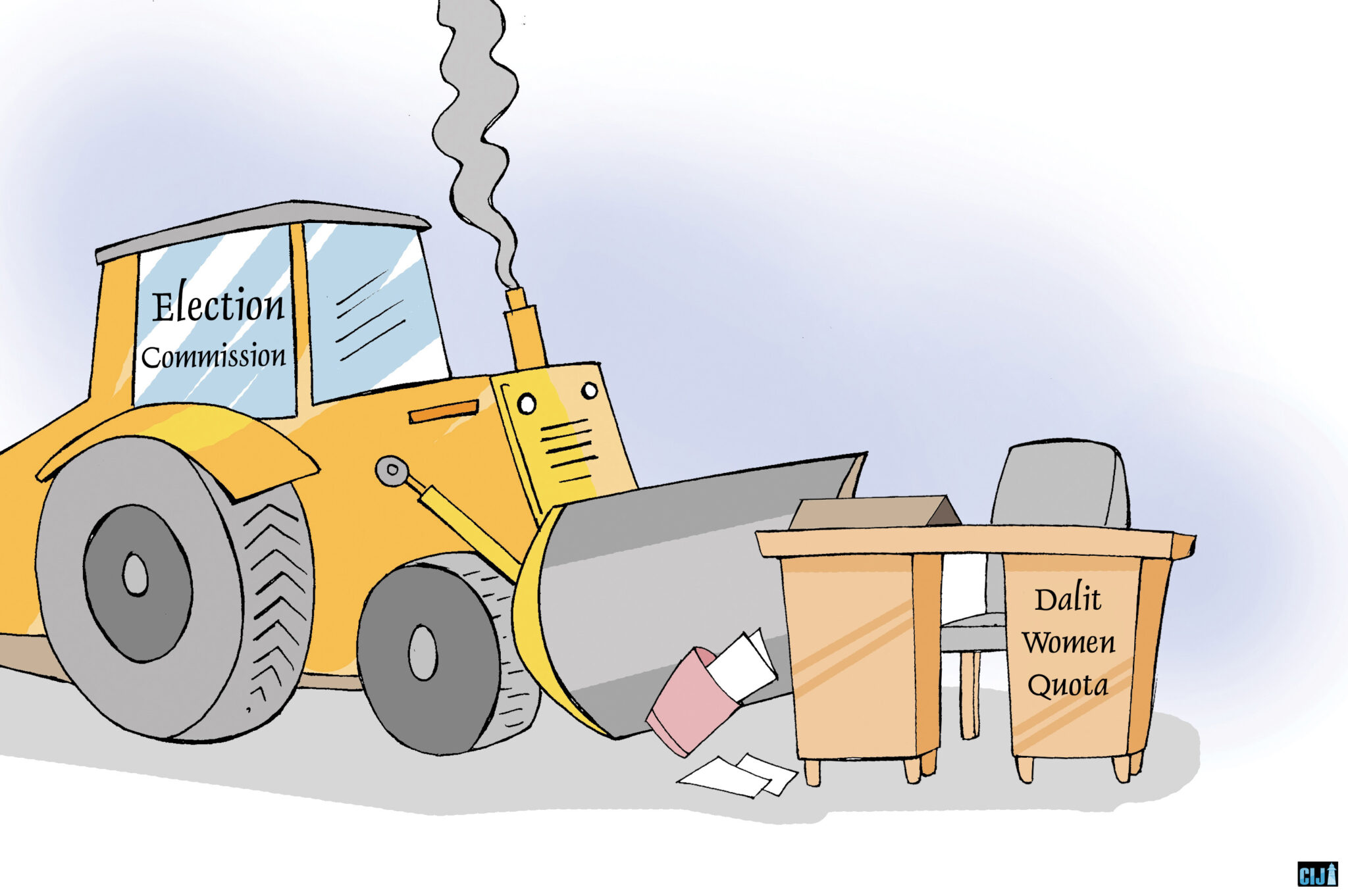

Leadership favours private health care

According to experts, high-level authorities at the Ministry of Health are the reason why public healthcare in Nepal has gone into disarray. For Dr. Anup Subedee, the authorities have failed to explain the importance of specialist doctors to ministers.

The authorities, though, claim the ministers exert pressure to form policies that are in line with the interests of private health care institutions. “Leaders of big political parties own medical colleges and hospitals, and the operators of such institutions pressurise us to form policies of their interests on the backing of the political leaders who are close to them,” a high-level official at the ministry said.

Investors manipulate policies in the absence of a political perspective on the health system, says Sachin Ghimire, a medical anthropologist. According to Ghimire, policymakers, politicians and investors are the same people, which is why the policies reflect the interest of the investors.

According to Amod Pyakurel, a medical anthropologist, if we look at the political credentials of investors in the field of medicine, it becomes clearer who has ruined the medical sector and why. “The political leaders and the administrators at the policy-making level are both inefficient, which is why investors influence them,” Pyakurel said.

A look at the political background of the medical sector investors shows the experts are not wrong. Dr. Sunil Sharma, the operator of Nobel Medical College in Biratnagar, is a shareholder of Kathmandu Medical College and Nepalgunj Medical College. Considered close to Nepali Congress leader Dr. Shekhar Koirala, he had contested the parliamentary elections from Morang District’s Constituency-3 in 2017.

Similarly, Basaruddin Ansari, the operator of the National Medical College in Birgunj, also has an investment in Nepal Medical College in Kathmandu. Formerly with the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist-Centre), he had contested the 2017 local elections for the mayoral position in 2017. Dr. Surendra Kanaudiya, the managing director of Nepalgunj Medical College, had contested the 2017 local elections for the mayoral position with a ticket from the Nepali Congress.

Durga Prasai, the operator of B & C Medical College (proposed), has a cancer hospital in Jhapa. Formerly with the CPN (Maoist-Centre), Prasai is now a leader with the CPN (UML). Khuma Aryal, an operator of Gandaki Medical College, is with the Nepal Congress.

Umesh Shrestha was appointed as minister of health in July 2021. He runs Janamaitri Hospital and is also the president of Mahendra Narayan Nidhi Hospital.

Shrestha, who plans to open a boutique hospital named ‘Heloice’ in Ekantakuna in Lalitpur, has spoken of plans to establish hospitals in Chitwan and Nuwakot.

Even the officials of institutions established to secure the rights of medical professionals have their hospitals.

For Dr. Subedee, the policy has faced a drawback because the administrators are connected to politicians and politicians to investors.

“The failure to open positions for specialised services is just one example of the dozens of irregularities that investors have committed in connivance with administrators and politicians,” Dr. Subedee said.