Prime Minister Dahal, by crafting a narrative that singles out forests as the primary obstacles to development, seeks to facilitate land acquisition for opportunists and party members through amendments to the law.

Mukesh Pokhrel | CIJ Nepal

“We are revising laws that [until now], prioritise other things [like forest conservation]. Development halted by conservation laws will now resume. Afterward, I believe there will be a significant revolution.”

It’s not by chance that Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ delivered this statement at a CPN Maoist Center’s party office in Kathmandu on November 27th. Describing Nepal’s forest laws as “obstacles to development,” Dahal announced plans to address landless and squatter community issues through amendments to the laws within a week.

Within two months after the prime minister’s announcement to ‘start a revolution’ by amending the Forest Act, the bureaucratic machinery is at work to formalize the process. It all started with Prime Minister Dahal directing Chief Secretary Baikuntha Aryal to lead the necessary preparations to amend the Forest Act 2019. A team of secretaries from relevant ministries, including Deepak Kharal (Secretary, Ministry of Forests and Environment) and Gokarnamani Duwadi (Secretary, Ministry of Land Management, Cooperatives, and Poverty Alleviation), is drafting an amendment bill.

So, what is the ‘revolution’ Prime Minister Dahal aims to bring about by amending the Forest Act? A joint secretary from the Ministry of Forests and Environment disclosed that the prime minister initially sought to distribute land to squatters and landless through the Land Commission. However, as it lacked enough legal teeth to do so, he now wants to amend the Forest Act itself.

“Under increased pressure from the Land Commission and the Ministry of Land Management, the prime minister appears to be taking a more assertive stance,” he remarked. “The prime minister also faces pressure from various interest groups aiming to acquire forest land across the country for commercial purposes.”

Forest Land Intrusion: Homes Sprout in Kalakate, Bridging Dang and Arghakhanchi Borders. Photos by Mukesh Pokharel

During internal discussions on amending the Forest Act, Prime Minister Dahal tends to focus on around 1.3 million slum dwellers and landless families. A senior official engaged in the deliberations says, “The government is gearing up to distribute land parcels to 1.3 million families.”

The National Land Commission, established in 2021 through a government order, has so far compiled data concerning 1.35 million landless, squatter, and ‘irregular settlement’ families. The government is going to allocate land to a minimum of 1.3 million families from within this group.

Heading the preparations is the National Land Commission, with significant political appointments held by party workers. The commission had already made arrangements to distribute land to the 1.35 million. However, it couldn’t do so as section 12 of the Forest Act presents a significant obstacle. It explicitly forbids the use of any forest area containing trees for settlement or resettlement. Sub-section 2 even states that before the Act’s commencement, trees on land settled or resettled under existing forest laws shall remain the property of the Government of Nepal.

Commission officials signal their intent to amend the Forest Act to remove this provision. Nahendra Khadka, vice-chair of the Land Commission and a central member of the ruling CPN-Maoist Center said, “Where people have resided for 10 years, the land law stipulates that the land can be allocated to the respective individual. However, the Forest Act poses an obstacle to this,” he explained. “Hence, the Act had to be amended.”

Section 52 (b) of the Land Act 1964 allows for the provision of land to the landless and squatters. Sub-section 1 states that the government of Nepal can allocate land to the landless squatters for one time in the place where they are settled or any other government land deemed suitable, without increasing the area limit.

Sub-section 4 explicitly specifies that regardless of other provisions, land cannot be allocated in public areas, river or stream banks, hazardous locations, national parks, protected areas, forested areas, and within the right of way of roads.

Nahendra Khadka, the vice-chair of the commission, states that among the 1.35 million families documented by the Commission, 80,584 belong to landless Dalit families, while 155,938 are landless squatter families, whose members lack any form of land ownership. Over 80,000 landless families that had remained undocumented by previous commissions, have also now been identified. Additionally, the commission reports 775,710 ‘irregular’ resident families, individuals who own land elsewhere but have been cultivating or living on government, public, and private land for an extended period.

Upon analysis, the commission’s figures seem unclear. The actual number of genuinely landless individuals and ‘irregular’ squatters, who simultaneously occupy public land in one area while being landowners in another, remains ambiguous.

Despite stakeholders advising against such actions, the plan has already been set in motion.

Sindhu Dhungana, director-general at the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, recognises the positive aspect of the proposal, which would potentially end land encroachment and establish definite boundaries. However, he emphasizes that protected areas and national parks can’t be compromised. “While resolving disputes related to those residing on public land for an extended period is crucial, it should not result in encroachments on forests and protected areas,” he adds.

During the decade-long armed conflict led by the Maoists, the party encouraged the resettlement of landless and squatter communities to forest areas and public lands across the country. During that period, the party encouraged people to occupy both zamindars’ and public forest lands. While some settlements have been evicted from occupied lands in certain areas, the majority of these settlements remain.

Even after the Maoists gave up their violent insurgency and participated in the peace process, this pattern continues. Instances like those in Shivnagar in Kapilvastu, Attaria in Kailali, Tinau Khola bank settlements in Butwal, and the Sagarnath forest project area in Sarlahi serve as illustrative examples. These and various other locations now boast concrete houses and complete development infrastructure. Currently, under Maoist leadership, there is an effort to provide land ownership to the settlers and establish new settlements.

The announcement of Prime Minister Dahal from the Maoist office reveals much. A high-ranking government official remarked, “It appears that all Maoist leaders, including the Prime Minister, don’t know if or when they will return to power, so they want to do whatever is in their interest, fast.”

An indicative instance of the severity of the issue stemming from unorganised settlements by the Maoists is the community established in the Sagarnath forest project in Sarlahi. Over various periods, the Maoists have resettled approximately 3,000 families on the land allocated for the Sagarnath forest project in Sarlahi. Their votes carry substantial weight during elections, even determining the outcomes of victories and losses.

The same vote played a pivotal role in securing victory for Mayor Bharat Thapa, elected by the Maoists, in the local elections of 2017 and 2022 for Sarlahi’s Bagmati Municipality. In Ward No. 4 alone, during the Land Commission’s data collection, 2,000 families submitted applications. Among them, 1,800 registered their applications as irregular residents.

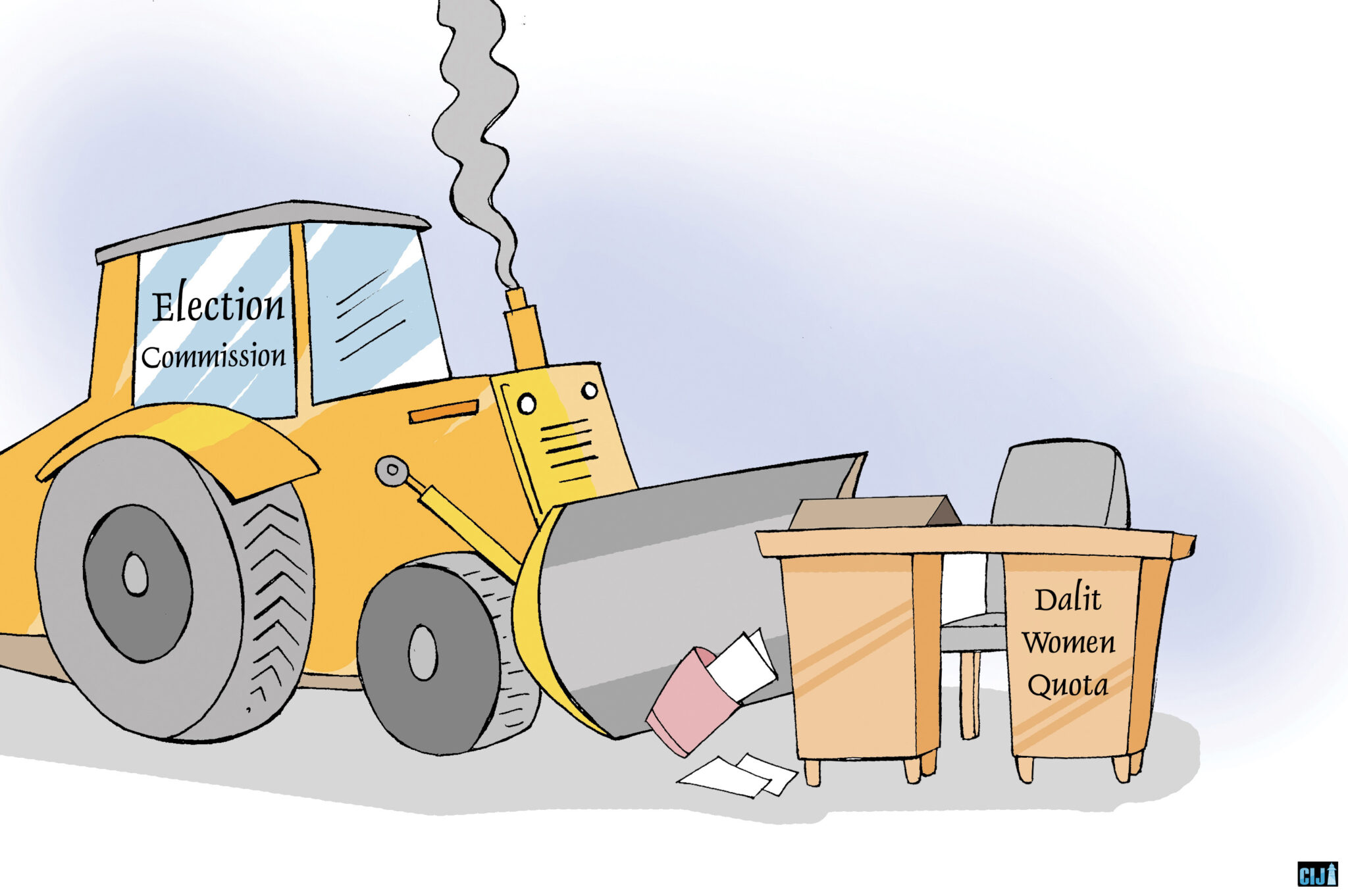

Providing land to the landless and squatters, who lack their own piece of land, is a common inclusion in the election manifestos of many parties. However, the necessary actions are often neglected after the elections, with catchy slogans merely employed to secure votes. Despite the challenges faced by the landless Dalit community, the Dahal government is now poised to extend beyond existing laws, granting legitimacy to those who have already occupied government and forest land under the guise of unorganised residents, and even lowering tax rates for them. Leaders of the ruling Maoist Center have been actively engaged in this effort, collaborating with land mafias who have encroached upon public land in various locations.

Claiming Public Space: Saljhandi’s Urban Expansion Along the East-West Highway in Rupandehi.

The government is even preparing to slash prevailing land tax rates for individuals occupying public and forest land under the label of ‘disorganized residents’. Nahendra Khadka, vice-chairman of the Land Commission and a central member of the Maoist Center, has confirmed this stance.

“Under the current regulations, the tax rates are excessively high, even surpassing the market rate,” he stated. “Therefore, we have decided to amend the law to alleviate this burden. Preparations are currently underway for the revision.”

Chief Secretary Baikuntha Aryal proposed reducing the price and registration tax of such land during a meeting with relevant ministry secretaries and joint secretaries approximately a month and a half ago. A participating joint secretary expressed disagreement, stating, “We argued that this is inappropriate; it should not be pursued. While advocating for providing free land to the landless, including Dalits, we should not allow the land mafia to occupy government land under the guise of irregular residents. Now, the situation with these land mafia activities has intensified.”

Nevertheless, extensive commercial and business structures constructed along the highway in Baraka Pathalaiya and Amlekhganj, Chisapani in Kailali, Dangkovalubang, and Gorusinge in Kapilvastu have been categorized as irregular residents. “For instance, a hotel is being operated by occupying government land in Chisapani, Kailali. How can we legitimize this? Let alone reduced taxes. There are numerous examples nationwide, and what’s happening isn’t happening for good.”

The Land Rules-1964 include provisions for categorizing land and determining the value of unoccupied land. Specifically, it sets the price for 1000 square meters of residential land with road access to the Kathmandu valley at a minimum of 15 million. This pricing applies similarly to agricultural land up to 10,000 square meters.

Likewise, the pricing for 875 square meters of land situated on roads wider than 8 meters in municipal (urban) areas has been established ranging from 1 million to 15 million rupees. The pricing is set at 7 million 10 million rupees for 750 square meters of land in urban areas of municipalities, and 5 to 7 million for 650 square meters of land in rural areas of municipalities. The government is in the process of considering a reduction in these prices. A joint secretary remarked, “This is not intended to benefit the landless but rather to facilitate the land mafia.”

The ongoing discourse surrounding the forest sector often revolves around the dichotomy of ‘forest vs development.’ In other words, regulations and laws pertaining to the forest sector are perceived as impeding developmental efforts. This sentiment, primarily voiced by the private sector, has been a longstanding concern.

Efforts to tackle these challenges have already started, with the introduction of new provisions aimed at addressing obstacles in acquiring land within forest and protected areas for development projects. The streamlining of development work has been facilitated through the revision and issuance of updated forest-related procedures and guidelines. However, that doesn’t seem to be enough for the prime minister.

The newly-issued procedure to provide land for the development of infrastructure inside protected areas has facilitated a more streamlined process. The procedure, published in the gazette on January 4, has opened avenues for the development of infrastructure within protected areas.

As per the procedure, developers are now allowed to construct infrastructure, including power plants, within protected areas upon receiving permission from the government. Under the new arrangement, hydropower projects up to 25 megawatts need to release 15% of water in the dry season, projects ranging from 25 to 100 megawatts will release 15%, and projects exceeding 100 megawatts will release 10% of water during the dry season.

The previous version of the document specified that when damming or diverting a river or stream within the boundaries of the national park and wildlife reserve, the respective river or stream should be left open to allow for at least 50 percent of the natural flow.

Nature’s Loss, Settlement’s Gain: Shivgarhi Welcomes a New Neighborhood Amid Kapilvastu’s Woodlands.

Ganesh Karki, chair of the Independent Power Producers Association of Nepal (IPPAN), acknowledges that the new procedure has addressed the long-standing demands of hydropower developers. However, he raises concerns about the substantial payment required if land is not available in exchange for acquiring land within the protected area.

“Several of the concerns we have been advocating for have been addressed. However, the compensation amount for land has surged significantly,” he stated. “This substantially inflates the project cost. We believe this is unfair since the project we construct will eventually become government-owned after a certain period.”

According to the new procedures, if a project can’t offer land as an alternative within protected areas, the compensation rates are set at 15 million per hectare in the Terai region, 7 million in conservation areas, and 3.5 million in buffer zone areas.

Likewise, for projects involving protected areas in Chure and inner Madhesh, the compensation rates are established at 126 million rupees per hectare, 6.6 million rupees per hectare, and 3.3 million rupees per hectare respectively.

In the hilly and Himalayan regions, the compensation rates for protected area land is set at 9 million per hectare, 6 million per hectare in conservation areas, and 3 million rupees per hectare in buffer zone areas.

Conservationists express concern that this provision has been overly lenient, heightening the risk of encroachments into parks and protected areas. Dilraj Khanal, an expert in international law on natural resources, asserts that the government’s actions appear to favor specific businessmen and interest groups, promoting the clearing of protected areas.

“It is incorrect to establish a hydropower project anywhere with the sole aim of quickly gaining wealth through electricity sales,” he argues. “We should carefully assess our electricity needs, determining the location, river, and the quantity of electricity to be generated. This process should be approached systematically. However, currently, permits seem to be granted haphazardly based on traders’ requests.”

Sindhu Dhungana, director-general at the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, explains that in the case of projects deemed nationally significant and sanctioned by the Investment Board, utilization of land within protected areas will be considered when no alternatives are available. He asserts, “Halting development and construction everywhere is not practical; development initiatives should proceed with clear plans on locations and objectives. It is also unjust to hinder progress for the sake of conservation everywhere.”

Dhungana reports that efforts are underway to revise the regulations, aiming to overcome hindrances posed by the current rules in the development of conservation and buffer zone areas. He adds, “Numerous challenges have arisen as laws similar to conservation areas were imposed on buffer zone. Discussions are ongoing to amend regulations and assign responsibility to the local level for addressing these issues.”

The Environment Act-2019 and its regulations grant the provincial government the authority to approve detailed Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports for projects at the provincial level. Madhu Ghimire, under-secretary at the Environment and Biodiversity Division of the Ministry of Forestry and Environment, notes that as a result, the burden on the center regarding EIA has significantly decreased. She adds, “The delays experienced before reaching us cannot be attributed to forest-related issues.”

Experts argue that in the face of revealed development obstacles, the attempt to distribute new land through legal amendments and legitimizing the previous occupation of public land is a concerning trend. Rajan Pokharel, former director-general at the Forest Department, warns that providing encroached land and further distributing land in this manner poses a risk to the existence of Nepal’s forested areas.

Urbanization in the Woods: Shamserganj’s Forest Enclave in Banke District Morphs into a Cityscape.

“If economic interests and political motivations of a few drive forest land distribution, it risks depleting the forest. The law explicitly bars forest areas’ use for other purposes to prevent degradation,” he emphasized. “As other development barriers ease, adopting a land distribution policy based on individuals and party workers is unwarranted. If land allocation is necessary, the government could acquire and distribute from private individuals.”

The Ministry of Forests and Environment’s spokesperson, Badri Dhungana, dismisses blame for delays in environmental impact assessment (EIA) approvals directed at the Ministry of Forest. Dhungana argues that consultants conducting the EI are responsible for delays, asserting the Ministry can approve an EIA report within three months of submission, and it is not at fault.

Several instances highlight such concerns. Last month, Nepali Congress MP Deepak Khadka raised the issue with the Ministry of Forests and Environment, claiming that his company faced unnecessary hurdles in getting the EIA approved for its Hotel Forest Inn in Budhanilkantha, Kathmandu, on the buffer zone of the Shivapuri National Park. Khadka, who visited the ministry with a group of YouTubers, organised a sit-in at the ministry demanding that it give the go-ahead for his project. However, the delay was caused due to Khadka’s reasons, not due to issues with the ministry’s EIA approval for his hotel.

Hotel Forest Inn Pvt Ltd submitted its initial documents to the Ministry of Forestry and Environment on Oct 30, 2018. The work evaluation and mandate report was approved on March 17, 2019, and the permission for EIA was also subsequently granted. Following this, Khadka’s company delegated the EIA report preparation task to Nepal Development and Consultants Pvt Ltd.

However, the company went ahead with construction work without waiting for the ministry to approve the hotel’s EIA report. After the construction work was completed, it submitted the EIA report to the ministry for approval on August 28, 2023.

For constructing the hotel without EIA approval, the Ministry of Forest and Environment imposed a fine of 500,000 rupees on Khadka’s company on November 7, 2023. Subsequently, another EIA process was initiated. Khadka, however, used his access and power to confront the minister in his office demanding that the EIA report be approved.

Malpractices related to the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report extends to projects such as the renowned Nijgadh International Airport. Portions of the EIA report were found to have been ‘copied and pasted’ from that of a hydropower project planned in the Gaurishankar area of Dolakha. This issue stirred controversy when the report was hastily approved by the Ministry of Forests and Environment in June 2018.

Meanwhile, Maoist leaders abreast with the recent developments in the forestry and conservation sector, say that Prime Minister Dahal is aiming for greater flexibility in forest sector-related provisions, and is revising the law before the upcoming parliamentary session. The prospect of the prime minister altering the law and facilitating the distribution of forest land from individuals to businessmen raises uncertainties about long-term consequences for conservation.

Concerned individuals highlight the potential for a dire situation. “We will operate within the confines of the law. If the political party in power asserts that forests are not important, how long can the solo effort of bureaucrats save it?” states Badri Dhungana, spokesperson for the Ministry of Forestry and Environment. He adds, “If the activities proceed as stated and requested, we won’t have much forest left in the country in two years.”