A Majhi settlement in Kathaar, Chitwan has turned into a ‘slum’ to supply servants to the local elite and political parties. This is the sad story of a settlement that looks like any other from the outside. But the residents here are yet to become the state’s citizens.

Pratima Silwal |CIJ, Nepal

After heading south for around 7 km from Khurkhure, Chitwan, on the east-west highway, one reaches a small market area. This is the Kathaar bazaar in Khairahani Municipality-10. The ward office is located right next to the entrance of the bazaar. If one heads around 500 meters towards Kathaar Secondary School, one can reach a settlement that looks ‘tidy’ from the outside.

But the settlement with 130 residents is anything but tidy. By looking at the people here, we attempt to dig into the dark side of Nepali society.

Majhi Vasti in Kathar, Chitwan, where the residents have yet to become citizens. Photos: Manish Poudel

The houses in the settlement are of the same size and colour as all of them were built by the government over the previous two fiscal years (2020/2021 and 2021/22) by spending Rs 12.5 million.

It was in one of the houses of the settlement where on the evening of May 26, Ramchandra Majhi and his wife Geeta were drinking alcohol as they ate dinner. A drunk Ramchandra asked Geeta to get ready for sex. But Geeta didn’t comply. According to the statement Ramchandra, who was in prison, gave to the police, when his wife could not satisfy his sexual appetite, he forced his hand and a piece of wood into Geeta’s anus and vagina, injuring her badly.

Geeta breathed her last on May 30 while receiving treatment. “Our father used to thrash our mother accusing her of sleeping with other men. When we tried to intervene, he used to beat us as well,” said 14-year-old daughter Sushmita.

Almost all of the 28 houses in the settlement have similar stories of poverty, illiteracy and violence to tell.

On that evening when Ramchandra attacked Geeta, even the neighbours next door didn’t act to save her even when they heard Geeta scream as this kind of beating, shouting and brutality has been normalised in this settlement. ” Not a single day goes by without a woman being beaten by her husband and without a fight between couples,” said Gayanti Paswan, a resident of the settlement and a ward member.

When Geeta was admitted to Bharatpur hospital, her sister-in-law Uma showed this reporter a wound on her own hand and said, “After drinking alcohol, there is not a day when the men don’t abuse or beat their wives.”

The clock seems to be ticking backwards in this settlement in Chitwan, a district located in the middle of the country, and considered relatively more developed. The residents don’t remember much of their past. They don’t even have recollection of personal events in their own life. Most of the residents of the slum are unaware of their own date of birth, and only 12 in the village have citizenship certificates.

Except in the case of women who came from outside the settlement, none of the families have registered any marriages, births or deaths. The mother doesn’t know when her children were born. Most fathers are drunk during the day and the night. Those who aren’t drunk are ill. No one cares about the scuffles and fights that erupt so frequently.

None of the young people aged 18-20 are in college. Most of them have already become mothers and fathers.

Bawan Mahato (50) says that he has been observing the Majhi community in this area since he gained consciousness. According to him, the fisherfolk who live on the banks of the river belong to the community, known as Musahar in the Tarai.

Kaushila’s sorrow, Gayanti’s loss even in victory

Kaushila Majhi, who lives in the first house of this settlement, is 20. Although there is a school in front of the house, she didn’t go there. When she was nine, her mother Merkhunia and father Nika Majhi sent her to a hotel in Birethanti to wash dishes.

When she was 12, she returned home and got stuck in daily wage. But she dreamt of freedom from constant labor and poverty. Ravi Chaudhary lived in a village nearby. The duo eloped to get hitched without the consent of their parents..

Kaushila Majhi and Gayanti Paswan

“The parents filed a police complaint. Officials gave them a document saying that they can’t get married at such a young age,” Kaushila said, “But returning to the village, the villagers handed me over to Ravi as no one wanted a woman who had already eloped with another man.”

The duo then tied the knot and for a few years after their wedding, Kaushila’s life seemed to move ahead smoothly. After that, Ravi was involved in extra-marital affairs, and started beating his wife.

“He has already married four women, including me. He even ran away with my sister-in-law. But when my brother filed a complaint, he returned her to him,” Kaushila said.

Kaushila is five months pregnant. After Ravi brought in another girl, she took refuge at Ravi’s brother’s place along with her daughter.

Two days after the death of Geeta Majhi, the villagers cremated her on the banks of the Rapti. Jitan Majhi (20), who went to the funeral, returned home drunk. He quarreled with his wife Sanju (18), who was one month pregnant, accusing her of not cooking good food.

“He kicked me saying that he will make me another Geeta if I don’t obey his orders,” said Sanju. Ward member Gayanti Paswan came to know about the incident as she hadn’t forgotten Geeta’s death. That must be why she called the police. But Sanju didn’t agree to file a complaint as she was worried there wouldn’t be anyone to feed her if her husband went to jail. Jitan returned home after spending a night at the police station.

Sushma Majhi, who was married as child, is beaten by her husband every now and then.

When Sanju from Kolhvi in Bara came to her aunt’s house to harvest mustard, her father had arranged her marriage with Jitan. Both Jitan and Sanju don’t have citizenship. They don’t know how they can get it.

It’s not just 18-year-old Sanju, 60-year-old Chinguri Majhi shares a similar story. Chinguri, who married Bhola Majhi (around 65 years old) after the death of her first husband, said, “I would have remembered if I had been beaten on one particular day. But it’s hard to keep track when you are beaten up day after day!”

At 11 in the morning, while Chinguri shared her grief with this reporter, her husband Bhola was wandering the street drunk.

Thirty-seven-year-old Gayanti Paswan was elected ward member in the recent local elections. Gayanti, who took part in a victory procession after the announcement of the results, reached home with a face smeared in vermillion powder and a neck full of garlands. Before she could enter the house, her husband Ram Gosain beat her to the point that she became unconscious. The reason: she marched with men.

“During the election campaign, I was beaten for riding a pillion on someone else’s motorcycle. He also beat me for making eye- contact with other men in the procession,” said Gayanti.

Ram also spent a month campaigning for his wife during the election. “We walked together all day, when we reached home in the evening, he would beat me up,” Gayanti said. ” When we got home, he would take random names of men who participated in the rallies and beat me for talking to them or looking at them.”

Married for 15 years, the mother of four earns a living by taking care of pregnant women and washing dishes at wedding parties. She said, “The people here quarrel after drinking alcohol. When the man overdoes it, the woman even abandons her children and runs away.”

‘The choices I made’

Three days after Geeta Majhi’s death, 35-year-old Jayashree Majhi, who was loitering in the settlement at 8 am, didn’t appear drunk. Any other day, he would have been drunk, but he didn’t have money for alcohol that day. So he poured his heart out.

Jayshree Majhi whose house is in ruins due to her uncontrollable drinking.

His wife Phool Kumari abandoned her three children five months ago and started living with her parents. In Phool Kumari’s absence, the family’s kitchen remains shut. The children have stopped going to school. Jayashree, who is suffering from severe alcohol consumption, can’t even work.

“She used to run a grocery store in the village, and we could buy essentials from that income. The children used to go to school,” said Jayashree,” She left me because of my choices. When I started drinking too much, I couldn’t go to work. I tumble while walking. The children ask me to go get their mother, but I don’t have the courage to stand in front of her.”

Jayashree says that Phool Kumari still sends food and some expenses for her husband and three children.

While talking to Jayashree and moving forward, this reporter met Santosh Majhi, who was already drunk. As he is one of the 12 citizenship certificate holders of the slum, Santosh considers himself special.

The previous night, he had beaten his wife and son and driven them out of the house. He showed the bag in his hand and said, “I went to buy a bandage because my hand was bruised. On my way back, I drank 25 rupees worth of alcohol as I had Rs 100 I received for loading straw in the tractor in the morning.”

Last night, he was injured in a fight with a neighbor. He said that other men in the village used to stare at his wife and that was the reason for the fight. “My wife and son left me yesterday evening. I have citizenship. I am bigger than the people here, ” He said in a drunken tone.

Attempts at citizenship

Empi Majhi and Jhinka Majhi also don’t have citizenship. They don’t even know their age.

Yampi Majhi, despite living in Majhi Basti for two generations, is denied citizenship.

Empi said, ” Earlier when talking about citizenship, people used to say that you aren’t going abroad, or owning land. So why do you need citizenship? We thought so too. Now I know that citizenship is necessary.” She said that when she was young, she came to this place with her parents from Simara in Bara and stayed here.

Earlier, they had visited the district administration office under the leadership of Ward President Kariram Mahato to get citizenship. The chief district officer looked at the senior-most member of the group and asked, ‘Where do you come from?’ The old man, who had been drunk since early in the morning, woke up and said that he came from India. We also did not get citizenship,” said Empi.

Ramu Majhi, who voted in the elections from the 1990s to 2006, says that the citizenship distribution team that came to the village in 2006 asked them for many documents, but they did not issue citizenship certificates.

He said, “We even went to see the CDO in Bharatpur, but they didn’t issue us citizenship. The elderly died in hope.”

Ramu wants to send his son to work abroad, but he is unable to do so without citizenship. Ramu’s wife has a citizenship certificate she was issued under the name of her father. However, her children’s birth couldn’t be registered with that citizenship.

Bawan Chaudhary, who says that the Majhi population has been living here since the 1960s, insists that the people of this community should get citizenship on the basis of residence. “Citizens living and working in this country should get citizenship. Let the government investigate, we are ready to sign the bond.”

The seventh grade hurdle

According to local school records, 37 children from the slum are admitted to the Kathaar Secondary School this year. Among them, only one has reached seventh grade. Vinod Majhi, the student who also stood first in his class, did not take admission in class eight.

He said that he couldn’t go to school because of the quarrels at home. He didn’t even have his birth certificate and he couldn’t make a single friend at school. He said, “I don’t want to go to school.”

Kathaar Secondary School

According to Bhumilal Sharma Subedi, Head of District Education Coordination Unit of Chitwan, all students need to submit their birth certificate to the school before they sit for the district-level examination in class 8.

According to Kathaar school Principal Krishna Prasad Ghimire, Munnilal Majhi and Amir Majhi of the Majhi settlement reached class 10. However , they couldn’t pass their SEE five years ago.

According to the data from the school, currently eight children of this settlement are enrolled in the pre-primary level. Similarly, 26 have been admitted from class 1 to 7.

“However, more than half of them do not come to school,” said Principal Krishna Prasad Ghimire.

Krishna Prasad Ghimire, Principal, Kathar Secondary School

Ranjita Khanal Devkota, community mobiliser at Lumanti Housing Support Group for Shelter, which is working for the education of the children of Majhis, said, “There are more dropouts at the primary level because parents are not aware that their children should be sent to school regularly.”

According to Devkota, the community mobiliser, most of the parents in this community leave home early in the morning to earn wages and if there is no food in the house, the children follow their parents.

One morning when this reporter visited the settlement, a child, around 11 years old, was playing on the street. Even his parents, who said that he didn’t go to school because he didn’t have a copy-bool, were not enthusiastic about sending their son to school.

When this reporter visited his school, it was found that the second-grader was told not to come to school for a few days. A teacher said that as the school was trying to change his behaviour of beating younger students, one day he was found caressing the sensitive parts of a girl studying in class 1.

Principal Ghimire said that most of the children in the community show aggressive behavior. However, it is the experience of the teachers that the learning ability of Majhi community children is better. Some children have even topped their class.

Mental illness expert Dr CP Sedhain, children become aggressive due to constant quarrels in the family and unruly behaviour of parents. That’s when they suffer from ‘faulty learning’.

Dr Sedhain said, “Due to the wrong behaviour of the family and society, they become bullies and may even develop a criminal mentality in the long run.”

No one reports crime

Ramchandra was arrested four days after Geeta Majhi’s murder, but no one was filed a complaint against him. Superintendent of Police of Chitwan Navraj Adhikari said that police took on the case on the basis of an investigation as no complaint was filed.

The day after the incident, Pushpa Majhi, the elder daughter of the deceased, tried to lodge a complaint with the police. However, as she didn’t not have any identity card, the complaint was not registered.

Sushmita Majhi and Nisha Majhi on the last day their mother, Geeta Majhi’s funeral.

District Police Office, Chitwan has recorded 18 different criminal incidents in the Majhi settlement until last May. One of them is the murder of Geeta Majhi and two others are related to drugs. The remaining 15 are related to domestic violence and assault. However, Superintendent of Police Navraj Adhikari says that no complaint has been filed for any of the incidents.

Violence against women, drugs, child marriage, domestic alcohol production and consumption are the major criminal activities observed in the slum.

Although there is such a dire situation in the settlement, local party leaders and people’s representatives aren’t doing anything about it.

Chandravikram Chaudhary, who was elected as the ward chair, seems to have no knowledge about the settlement and its problems. Asked about the slums, he said, “There is a lack of public awareness. We need to raise awareness.”

Stating that he didn’t know much about the issue as he assumed office recently. He further added, “I have just taken charge, I will now work for them.”

Former ward chair Kariram Mahato claims that he built houses for the residents during his time in office and took initiatives to help them get their citizenship. He said, “We have also tried to change their behaviour. We taught them to raise pigs to help them develop economically. However , they killed and ate them or sold them prematurely. We trained them in sewing-cutting and gave them sewing machines. However, no matter how hard we tried, we could not change their behaviour.”

Kavita Upreti, deputy mayor of Khairhani Municipality, said that she came to know about this settlement only after Geeta Majhi’s death. She said, ” It is as if there is no consciousness, no human thought in the people of this settlement.”

She said that the problem of this community is a challenge for her tenure. She added that her focus is on spreading awareness in the community, and providing income generation opportunities. He is of the opinion that a continuous program should be brought in a new way to make children attend school regularly and to change the behavior of community members.

Extremely marginalised

Revati Pandey, who lives about 100 meters east of the Majhi settlement, moved to Chitwan from Nuwakot 40 years ago.

According to him, only Tharus are native to the place. “Later, many other communities came and there was an inter-mixing of cultures. However, the dalit fisherfolk were isolated,” he said. “Their population increased, but they couldn’t participate in community’s activities.”

Meera Chowdhury, a member of the ward 10 and a social activist, said that even when she tried to organise adult classes, and encourage Majhis to save money through cooperatives, the idea failed.

The relationship between Majhi and other communities is just like master and slave. If members of the community need some labourers, they call the people from the slum. They give them wages, but they don’t actively participate in festivities. Children of the members of the Brahmin, Chhetri and Tharu communities don’t even go inside the Majhi settlement to play.

A total 83 out of the 130 adult population of the settlement are eligible for citizenship. However, those who don’t possess land are also deprived of basic rights such as citizenship and registration of personal events.

Rewati Pandey, a resident of a nearby settlement, comments that the consciousness and state of development of the Majhi settlement is no different from what she saw 40 years ago.

Prem Rimal, a resident of Khairhani Municipality, east Chitwan, said that the Majhi community hasn’t received any motivation to move upwards in terms of awareness and development.

According to him, the majority of ethnic communities here faced a problem of identity and rights until recently. In this situation, dalit fisherfolk couldn’t be inspired to move forward. “They continue to be treated as suppliers of labour for others in the community. The selfish elite didn’t pay attention to the upliftment of the Musahar people.

Rimal says that because of illiteracy and extreme deprivation, the fishers are stuck in issues related to fish, mice and snails than to dream bigger than that. He says, “Even now, they are looked down upon. Therefore, the so-called knowledgeable people of the village or the local people’s representatives and parties aren’t willing to make an honest effort to uplift these marginalised people.

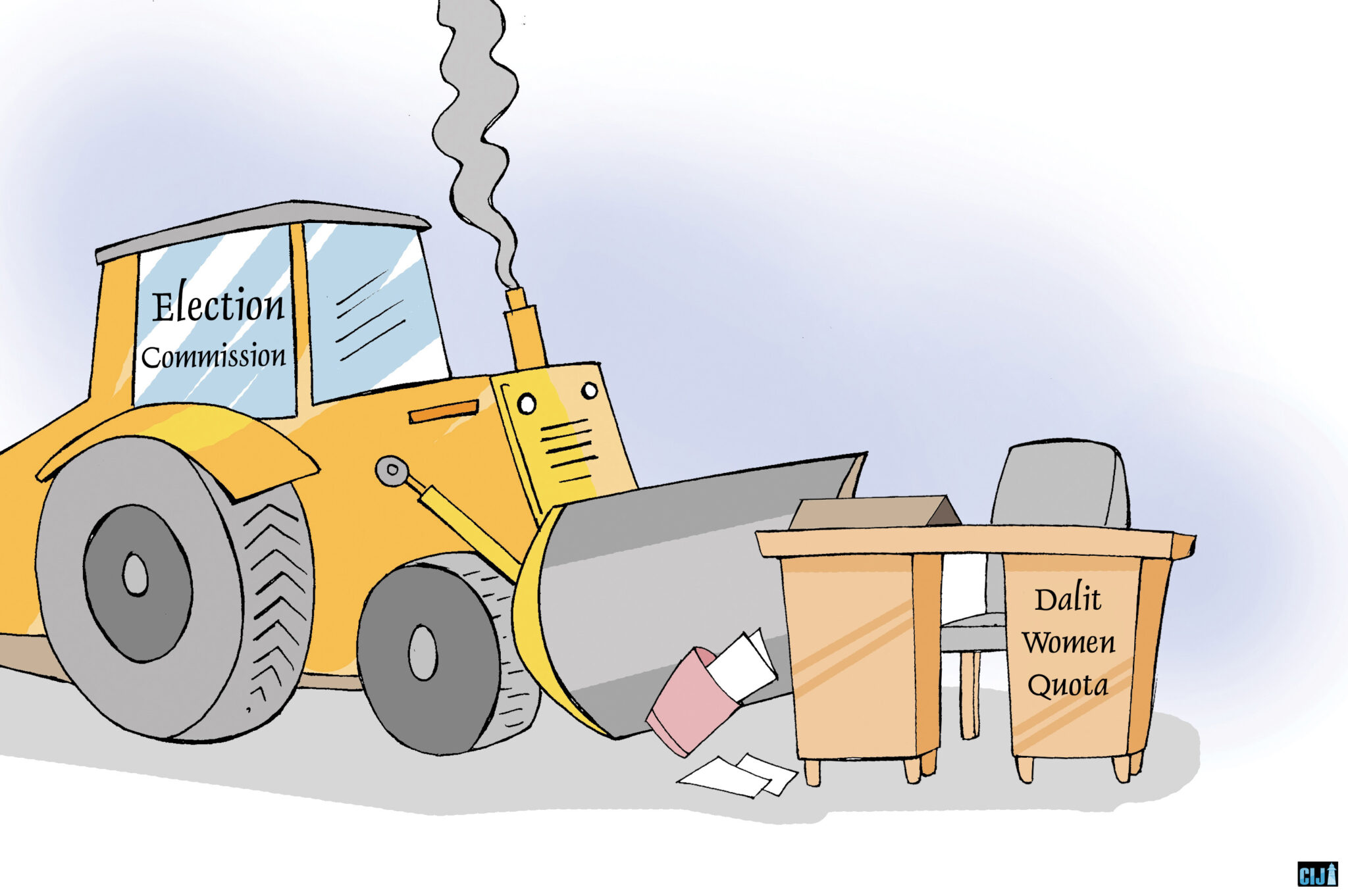

Rimal said, “The elite here only want to use this community. When the parties look at such a population, all they think about is using them to create trouble during elections and make them fake voters.”

Even in the integrated settlement built for them, Rimal smells political interests of the parties. He claims that this settlement was built in the name of a housing scheme to get a cut from the budget. He said, “The government built a house in the Musahar settlement as it would be easy for them to use it to suit their interest and to show that they are doing public welfare work. But they aren’t eager to make the people aware and provide them with other facilities.”

The Musahar slum can be a case study to show that the country’s political leadership doesn’t have the ability to implement a welfare system as envisaged by the constitution.

He said that in order to change this situation, a competent leadership with a clear vision and a strong will for development must emerge in the next election.

‘Maybe that’s what love looks like!’

Chinguri Majhi

I married him (Bhola) after my first husband Kapildev passed away. Kapil and I had four children when he died. I used to go to the river and bring snails and fish to feed the children there. I used to sell the rest. My mother-in-law didn’t like what I was doing. When Kapil’s mourning period was over, my sister-in-law said, “We are not obliged to look after your children!’. Her brothers-in-law also said they shouldn’t be expected to look after someone else’s children.

Bhola Majhi came looking for work. Looking at my condition, he took pity on me, so he held my hand. My two daughters have already tied the knot. The son I gave birth to with him is 12 years old. Jitan, who is Sanju’s husband, is my son from my first marriage.

Bhola goes to work and comes back after eating there. I wait for him until 12-1 pm. If I cook rice in the morning, he tells me not to do that. If I am hungry and I cook, he comes and beats me.

Two of my daughters and sons live in the same village as we do. He is suspicious that I will give all the rice to them. Even at this old age, he scolds me for making eye contact with other men. Sometimes I think he is expressing his love by beating me!

‘I am a man’

Bhola Majhi

I am a man. Sometimes it gets late at work. My wife asks me who I was with when I reach home late. We have committed any crime. I ask her not to cook in the morning as the food gets cold by the time we eat it. I earn by working as a manual scavenger. I run the house with that income. It is okay to drink alcohol together with my wife, but when I drink alone, she starts fighting. I drank alcohol after work this morning too. I didn’t fight with anyone. I cuss my wife. She also listens to what others say. She doubts my intentions even when I talk to her sister-in-law.