Young people, mainly from the Madhesi Dalit minority, are dying in police custody because the government isn’t doing enough to prevent torture.

Rohej Khatiwada | CIJ, Nepal

On October 10, 2021, 22-year-old Mohammad Hakim Miyan died at 3:15 am while in custody of the District Police Office, Sunsari. Following widespread protests, the Ministry of Home Affairs formed a committee to investigate the cause of death of the man from Bhokraha Municipality. But not only is the committee yet to report, the family doesn’t know the cause of his death.

On July 30, 2021, 40-year-old Paltu Ravidas from Laxminiyan, Dhanusha was found dead at the district police office. Although police said that he hanged himself to death at around 4 am, Paltu’s family doesn’t accept this. Danadevi, mother of the deceased, says, “He died due to wounds he sustained due to torture, but police are pretending that it was a suicide.” After Paltu’s relatives took to the streets after the incident, the federal government promised to provide Rs 1 million, the provincial government half a million rupees and Janakpur sub-metropolitan city Rs 150,000 to the deceased’s family. But they turned it down. With every passing day, they now feel that every glimmer of hope of finding out the truth about what happened to him is fading.

Shambhu Sada’s family. Photo: Tufan Neupane

On June 10, 2020, 24-year-old Shambhu Sada of Savila-12 Barakuwa, Dhanusha was found dead in the custody of the local police office. Although the police report about the incident mentioned that Sada hanged himself, his mother Sipalidevi doesn’t believe it. She had visited her son in custody every day, she says, “The police beat him every day, he used to cry saying that they would kill him.” Sada, a tractor driver, was arrested after the woman who was injured in a tractor accident died.

After Sada’s death, his family members also took to the streets demanding an investigation and punishment to the guilty. The government was forced to form an investigation committee. However, the report of the committee still remains under the wraps.

Police failed to record Sipalidevi’s attempt to make a complaint against the individuals she believed to be in charge of her son’s death. A complaint was filed in response to instructions from the public prosecutor’s office, but officials decided against conducting an inquiry.

On the advice of the provincial attorney’s office, the Attorney General’s Office authorized the district attorney’s suggestion to not pursue the matter. At the time that such a choice was made, Attorney General Ramesh Badal was in charge. According to Sipalidevi, Sanjay Saha, the owner of the tractor, and the police conspired to murder and torture Shambhu.

On August 17, 2020, Vijay Mahara, age 19, of Garuda-5 Banke in Rautahat was detained in connection with the murder of Niranjan Ram. On August 19, he was brought to Anamika Hospital.Vijay, who sustained injuries due to extreme torture, could not be treated at the hospital and was rushed to the National Medical College Birgunj.

Vijay Mahara’s family

In a video showing Vijay speaking from the bed of his hospital about the custodial torture he faced, he alleged that the police told him, “If you don’t confess to Niranjan’s murder, only your body will leave this custody.” Six days later on August 26, Vijay breathed his last.

According to police, Vijay died due to failure of both his kidneys, but the family alleges that he died after being manhandled by police. The deceased’s father, Panilal Mahara, filed a complaint saying that his son had died due to torture.

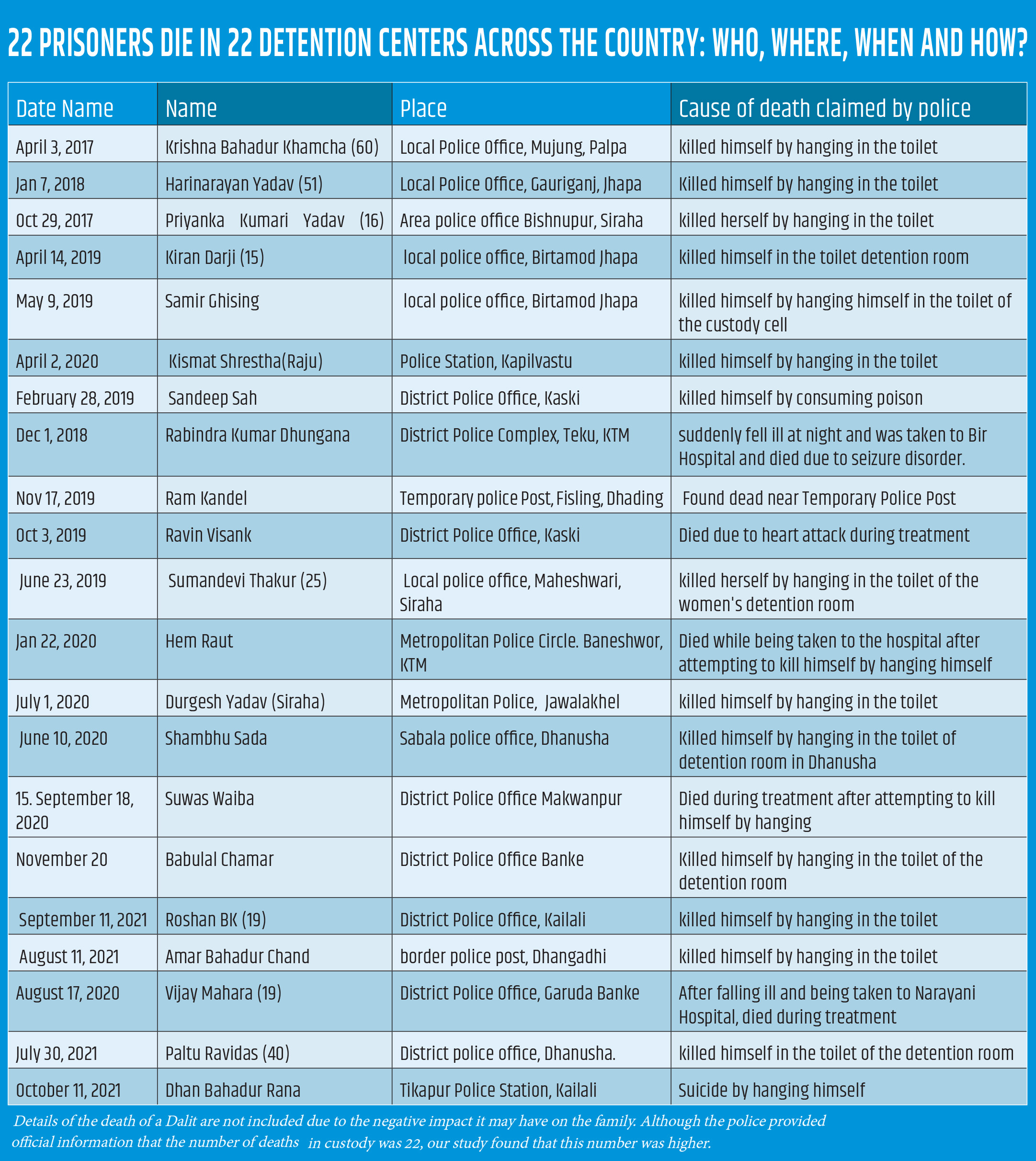

Twenty two people have reportedly passed away in jail throughout the course of the five years from the fiscal years 2016–17 to 2020–21, according to police headquarters. Fourteen of these occurrences include fatalities while in police custody on the nation’s plains.

Most of the cases of death of Dalit prisoners in custody in the last few years have been seen as suspicious. Families, activists, human rights activists and local residents have demanded investigation and action, saying that in most cases the death of the detainee was due to police torture or negligence.

In some cases, the government has suspended the responsible personnel for a short time. However, most cases don’t see credible investigation, nor are reports of fact-finding committees made public. Dalit rights activists allege that officials misuse state power to cover up such incidents and shield responsible police personnel.

A report published two years ago on the Indian online portal The Wire (https://thewire.in/south-asia/deaths-in-custody-impunity-nepal-police), states that 18 people died in custody in Nepal from June 2015 to June 2020.

The figure, based on news reports published in various media, doesn’t include “murders under control”. The figure, adjusted for population size, is far more than that reported in neighbouring India during the same period.

According to Human Rights Watch https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/12/19/india-kifll\ings-police-custody-go-unpunished, the number of deaths in custody in India is considered very high. In its report, it states that so far, there hasn’t effective investigation and prosecution of police involved in torture and deaths in police custody.

Another form of oppression

The majority of those who have died this ‘mysterious death’ in Terai’s custody are from the Dalit community. The government doesn’t seem interested in understanding why the people of this community, at the bottom of the social strata, are being detained more often. According to Nepal Police in the last five years, 8 out of 22 people who died in custody, i.e. 37 percent, are Dalits. While only 14 percent of Nepalis are Dalits.

The police reports on these eight cases of custodial deaths of persons belonging to the Dalit community are also controversial. Police claimed that in all the cases, the detainees killed themselves. The family, relatives and neighbours of the deceased don’t accept this claim.

Kisunbani Devi, mother of Vijay, who died in custody in August 2020, believes that her son died due to police torture. The wounds seen all over the body of Vijay, who was seriously injured due to torture and was rushed to the hospital, also strengthens Kisunbani’s claim.

The details of the cases of Shambhu Sada of Dhanusha who died in custody in May 2020 or Ravidas of Dhanusha who died in July 2020 leave sufficient grounds to doubt that all these Dalit youths killed themselves. However, no one involved in the incidents have been held accountable.

On April 14, 2019, Kiran Karki Dholi was found dead in the custody of Birtamod, Jhapa area police office. After his suspicious death, demonstrations erupted demanding an investigation. Jhapa’s Dalit rights workers came together to protest.

Because of the protest, the district administration office, Nepal Police and the Human Rights Commission formed separate investigation committees. The accused Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) Subas Khadka also formed a separate investigation committee. However, the reports of these four committees were not made public.

According to a human rights activist, before the incident took place, DSP Khadka, had a party at the police station till late at night on the occasion of ‘New Year’s Eve’ with the participation of some local leaders. Rights activists allege that after the party was over, he reached the detention cell at around two o’clock in the morning and beat up Kiran.

The family was not informed about the incident on the first day of the new year. The next day, Ramesh, father of the deceased, was directly called to Mechi Zonal Hospital, where Kiran’s body was taken for postmortem.

After the incident, Ramesh told the local correspondent of Kantipur Daily, Parbat Portel, “Looking at the bruises and injuries on the body, it is clear that my son was beaten to death.”

Ramesh said that the chief district officer has assured him that he will provide a job for his younger son. In this case, it is clear that instead of conducting a credible investigation into the suspicious death, police and other government agencies try to cover up the incident by influencing the victim’s family.

After Dalits, the Madhesi community has the largest number of deaths in custody. Among those who died in custody in the last six years, 10 are Madhesi (38 percent). During this period, two Madhesi women also died in custody.

In September 2019, 25-year-old Sumandevi Thakur, who was arrested from Saptari on charges of mobile theft, died. Police said that she killed herself in the toilet at around 7 am. Before that, on October 29, 2017, Priyanka Kumari Yadav of Siraha died in the custody of the Bishnupur area police office. In addition, during this period, four men from the community have died in custody, while five men are from the hilly/Bahun community.

Concerned that the poor, Madhesi, Dalit, Muslim and ethnic groups were victims in most of the cases of torture and death in police custody are, Amnesty International launched a campaign last year to ‘write a letter to the Prime Minister demanding a stop to the cases of death in custody’. It is said in the call, “Mysterious deaths in custody confirm that Nepal’s criminal justice system is problematic.”

Shivhari Gyawali, an active researcher in the field of Dalit rights, says that the treatment Dalits get in the society is reflected even in detention, and there are many deaths of Dalits there.

He says, “In society, non-Dalits beat and harass Dalits. They do the same in custody.” Gyawali is of the opinion that due to the ill-treatment and torture of Dalit prisoners even in custody, they are also encouraged to kill themselves.

“When police hide the evidence, it is not possible to confirm wether a death is due torture in custody or not.” Gyawali alleges, “But most deaths of Dalits in custody are due to murder.”

Torture room or detention?

The incidents of deaths in custody raise questions about the behavior of the police. Even more shocking are the public statements made by police personnel in such cases. According to the police, 14 of the 22 deaths in custody were due to hanging. And, in all those cases, the description is the same, “He/she died by hanging on the ventilator of the toilet of the detention room.”

The investigation teams formed by the police, the district administration office, the provincial government or the federal government are only a means to control the damage caused by the incident for the time being.

Kiran Karki Dholi.

“If such committees conduct serious investigations, many doubts about the police will be cleared,” says former Additional Inspector General of Police (AIG) Pushkar Karki.

Some independent surveys have also shown that detainees are tortured in detention cells. A report by Advocacy Forum, which regularly monitors prisons and detention cells, points out that one out of every five detainees has experienced some form of torture.

Bikas Basnet, a human rights activist associated with the forum, says that 20 percent of the detainees are being tortured.

In a 2006 study by another non-governmental organization, Terai Human Rights Defender Network, 167 (24.74 percent) of the 674 prisoners in 19 districts of Terai were tortured by police. Children and women were also among those tortured. Similarly, in another study conducted by the Alliance in 2017, out of 882 detainees, 118 people said that they were tortured.

During the 2015 Global Periodic Review (UN-UPR), Nepal received criticism from 73 countries for its weak human rights situation, including the practice of torture. After that, Nepal promised to treat torture as a crime and make it a subject of separate investigation. However, five years after the law was passed, no one has been prosecuted for death in custody.

Renudevi, wife of Paltu Ravidas. Photo: Rohej Khatiwada

The constitution has also given the attorney general’s office the right to prevent such cases. Article 158 (sub-section 6 c) of the constitution gives the attorney general the right to ‘investigate and give necessary instructions to the concerned authorities to prevent such incidents if there is a complaint or information that a person in custody has not been treated humanely or that such a person has not been allowed to meet with relatives or through a legal practitioner’.

According to the constitution, the Attorney General’s Office also monitors prisons and detention cells every year. Although the lack of physical infrastructure in the prisons is pointed out in the annual and prison monitoring reports, there is no mention of torture.

“More time is spent on formalities than on monitoring of torture,” says a lawyer.

The National Human Rights Commission also has the right and the access to monitor detention cells and rescue victims immediately, but the role of the commission has also been ineffective. During the armed conflict (September 16, 2005), the UN Special Representative (rapporteur) visited Nepal and prepared a report stating that torture is practiced as part of the system in Nepal to make the arrested persons confess to their crimes. At that time, no one in Nepal was held accountable even when the UN drew attention to the lack of laws making torture a crime. Even though such laws are in place now, no one has been held accountable.

The 1990 constitution stated that no one should face torture while being detained during investigation for a crime, and compensation should be provided if anyone is subjected to torture. The Torture Compensation Act, prepared to implement the said provision, provides that the victims of torture be compensated from the state fund.

Under this system, which legally recognized torture, the government would only pay a compensation if officials were found engaged in torture. Because of this, custodial torture was not recognized as a crime for a long time. Although the interim constitution made the act of torture punishable, it did not become a law.

The new constitution provides for the fundamental right to punish the torturer. Only then torture has been listed as a crime in the Criminal Code which came into effect on Aug 17, 2018. The code provides that a person who tortures or inflicts physical or mental torture on someone shall be punished with imprisonment for up to five years and a fine of up to 50,000 rupees or both. The code says, “No person who commits such an offense shall be entitled to claim that he has committed such an offense by obeying the orders of an officer above him and shall not be exempted from punishment.”

Such a law was made with the aim of preventing instances of torture that may occur on the orders of higher authorities within the security forces’ chain of command. However, not a single case of police brutality and torture, has been effectively investigated and prosecuted so far.

Father and mother of Mohammad Hakim Miya.

The crime of torture also attracts International law as as it is considered a serious crime against human rights. In other words, other countries make laws in such a way that they can treat cases of torture in Nepal as if they happened within their own country and take action against the perpetrators.

Based on the same law, a trial was held in Britain against Colonel Kumar Lama of the Nepali Army for torturing Maoist activists in the barracks of Nepal. The British court acquitted Lama in one case showing lack of evidence, while the British government withdrew another.

In January 2021, four UN special representatives (rapporteurs) wrote to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs expressing serious concern over deaths in custody. They referred to six incidents that happened within a year and called for investigation and accountability, but the government didn’t take any initiative to prevent such incidents.

Similarly, after the deaths in custody of Mohammad Hakim Miya in Sunsari, Dhan Bahadur Rana in Kailali and Durgaraj Pandey in Parbat, the Ministry of Home Affairs formed an inquiry and suggestion committee under the coordination of Joint Secretary Thaneshwar Gautam. Although this committee backed up claims made by the police in these three incidents, it suggested improvements to detention infrastructure, and installation of CCTV cameras.

Nepal Law Campus Assistant Professor Balram Prasad Raut says that human rights violations and torture are taking place in the country and perpetrators are getting immunity.

“There is still a lack of platform to seek justice for torture victims,” says Associate Professor Raut, “There are structural problems in Nepal’s courts and the government of Nepal has failed to adopt effective measures to prevent torture.”