Hundreds of thousands of students study in schools that have unsafe buildings, with an utter disregard for safety during earthquake or fire.

Rameshwar Bohara: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

School buildings line both sides of Lakhechaur Marga of Kathmandu’s New Baneshwar neighbourhood. These buildings of Vidhya Sanskar School were built 14 years ago by Chelsea International Academy. According to Shrishti Shakya, an administrator of the school, 1450 students take classes in the school’s 12 rented buildings.

Some 1,150 children study at Angels Heart Secondary School in Manmaiju of Tarakeshwar Municipality-10, Kathmandu. According to Principal Dhan Bahadur Pun, the school, founded 11 years ago, has rented four buildings including two five and a half storey and another two with four and a half floors each. In an adjacent plot, the school has built two sheds and a pre-fab building. The school has been housed in buildings that were built for another purpose. The school’s principal said they don’t have any plans to build their own buildings.

Usha Bal Batika Secondary School, founded in 1980, is run from a rented building in Birendranagar, Surkhet. The building, built by Padmdevi Karki in Buddha Path of Birendranagar -6, around 40 years ago, is dilapidated. It’s also congested for nearly 800 students. Teacher Madhu Joshi said, “The house is crumbling. We face problems walking into it.”

Lumbini Shikshyalaya, a private school, operates in an old and dilapidated building in Kalikanagar of Butwal Sub Metropolitan City. Madhu Sudan Lal Shrestha, a local businessman, funded for the building in 1986. Over 350 students take classes in the building as well as other seven tin-roofed huts. Outside the building, additional structures are being constructed for business purposes.

From grade 1 to 10, some 473 children study at Godavari English Secondary School in Biratnagar Metropolitan City-6. The school, founded in 1991, is housed in a residential building of Radha Rayamajhi. Principal Mahesh Kumar Jha said, “The house owner lives abroad, so we deposit the rent in his bank account.”

Lessons not learned in four years

The earthquake of 2015 left 8,856 people dead. It destroyed or damaged 812,161 houses, 8,308 school buildings and 502 health posts.

Despite huge loss from the earthquake, many people thank God for it struck on a Saturday, when schools were closed. What would have happened to millions of children studying at 8308 schools destroyed in the earthquake if the earthquake had struck on another day? It is difficult to imagine the fate of hundreds of children during the quake in schools without enough spaces, thereby making rescue efforts almost impossible.

It’s been three years and nine months since the earthquake. The tragic event has faded from most people’s memory. Earthquake-resistant houses are being built in remote, quake-hit villages. The damaged government school buildings are being replaced with stronger ones. Are lessons from the 2015 earthquake resulting on safer school buildings? A look into the state of rebuilding reveals that it has worsened over the years.

What’s the state of school buildings in Nepal? During analysis of 1,142 private schools and 272 government schools in Kathmandu, Nanda Lal Paudel, head of Education Development and Coordination Unit, said: “Most government and private schools are not safe here.” He added, “If a school doesn’t have an evacuation centre where the children can quickly reach in case of a disaster, then school building is not safe.” Most schools in Kathmandu are not safe; nothing was in place for the safety of the students before the quake and even after the disaster, their mindset hasn’t changed, according to Paudel.

The condition of Hatemalo Boarding School in Kolti of Budhinanda Municipality of Bajura district, where 400 children study, is no different. The school runs classes up to grade seven, but its building lacks basics. Students are crammed into the tin-roofed structure with mud and stone.

Ramhari Thapa, a school superintendent and section officer at the Education Development and Coordination Unit in Kathmandu, paints a grim picture of school buildings in Kathmandu. “80 percent of Kathmandu’s private schools don’t have their own building. Most of them are unsafe,” said Thapa. “50% government and community schools could be made safer, but there’s no plan to do so yet.”

Let’s take a look at Juddhodaya Public School in Kathmandu. There was a football ground on the school premises. That was turned into a shopping complex. It doesn’t even have a front yard.

= = =

In recent years, private schools have been set up in rural areas. Parents want to send their children to private schools. However, private school buildings lack safety measures. Nainsingh Khatri, President of Private and Boarding Schools Organization (PABSON) in Karnali province, said: “Only 10 percent of 131 private schools in Surkhet have their own buildings. The rest have rented residential buildings for the purpose.”

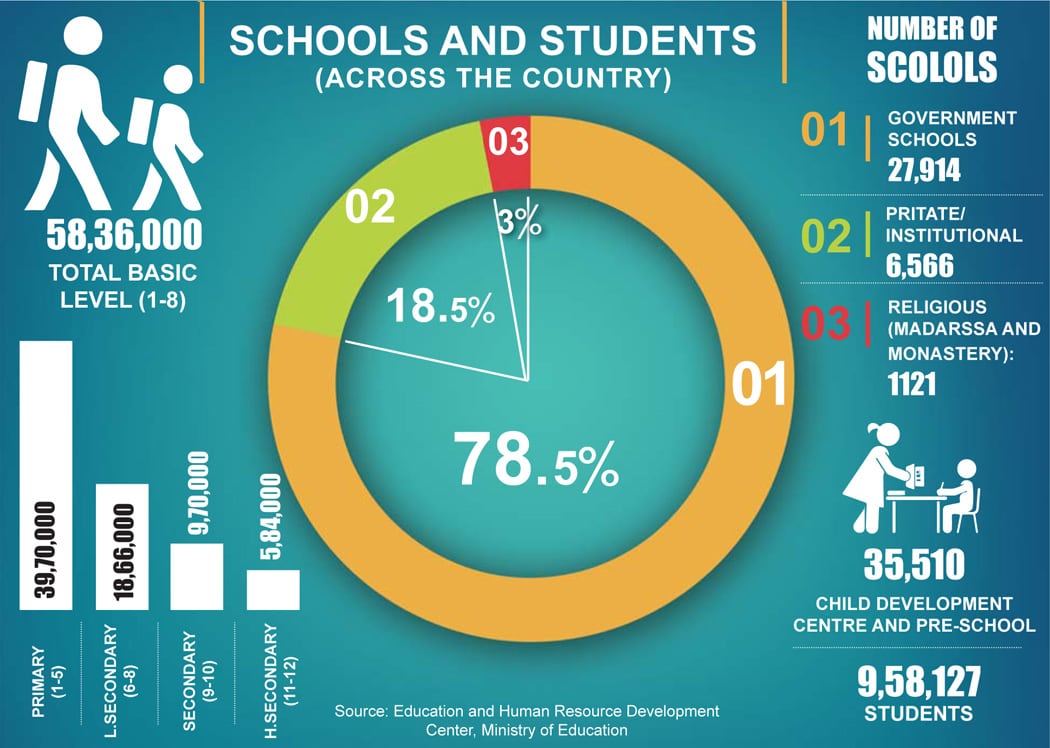

According to the Department of Education (Now Education and Human Resource Development Center), roughly 35,601 schools including Primary, Lower Secondary and Secondary operate across the country. Among them, 27,144 are government schools, 6566 private and institutional schools and 1121 religious schools (Madrassa and monastery).

Private schools have two organizations PABSON and National PABSON. We asked Bijay Sambahamphe, President of PABSON, which lists over two-thirds private schools as members, about the state of private school buildings.

“Only 5 to 10 percent of private schools in Kathmandu Valley have their own buildings. About 90 percent schools use rented house,” Sambahamphe said, “Outside Kathmandu, 15-20 percent of the schools have their own building.”

Around 1000 schools are affiliated with the Higher Institutions and Secondary Schools’ Association, Nepal (HISSAN), an organization of private high schools. Only 50 percent of these educational institutions have their own buildings, according to Lok Bahadur Bhandari, the General Secretary of HISSAN.

Neither board members nor parents seemed concerned about the issue of owning a building. Some people relate it to open space and infrastructure. As a result, the issue of children safety in these buildings is overshadowed.

Neither board members nor parents seemed concerned about the issue of owning a building. Some people relate it to open space and infrastructure. As a result, the issue of children safety in these buildings is overshadowed.

No one builds a house for a rent to school. Most buildings rented by school are for residential purposes. Dozens of students are crammed into a house which is built to accommodate a single family.

Senior Structural Engineer Dr. Rajan Suwal said, “The building can withstand the load only as per the purpose. If a school is run in residential building, it cannot withstand the load.”

The engineering design of residential buildings is different from others, according to Dr. Suwal. Normally family residential buildings are designed to limit their weight. When 40-45 students sit in a room in such a house, with desk and benches, it becomes unsafe. In case of an earthquake, when 40-45 students try to escape through narrow staircase, it causes problems.

“Since these buildings’ structure cannot withstand the load, many people can get killed in case of earthquake,” said Suwal. “After renting residential buildings for education, some schools have even used upper floors to run classes.”

A private school named Akshar Academy is run at the residential building of Manmohan Singh of Gadi Tole in Butwal Sub Metropolitan City-1. Singh’s family lives in the upper floor. Amar Pathak runs the school in the lower floor. Classes run even in spaces designated for parking. Around 250 children study at the grade 3 school.

Most of 300 private schools in Rupandehi run in residential buildings. Loknath Gyawali, President of Parents Association, Rupandehi, said, “Because the schools should vacate houses as soon as the landowners say so, they do not even repair the buildings. As a result, the students, the teachers face the risk.”

A report submitted by a panel set up by the National Planning Commission after the 2015 earthquake said: “The building should seek an approval from municipality if he or she is using it for purposes other than as specified in the approval. For example, buildings approved for residential purpose cannot be used for institutional (school, college, hospital or commercial) purpose. If the purpose of the building is to be changed, the owner should get an approval from municipality without changing the building’s standards.”

Kathmandu Metropolitan Municipality issued a Building Construction Certification Mechanism, 2016 after the earthquake to stop the practice. The regulation says: “Some houses approved for individuals by Metropolitan City have been to have transferred to organizations, companies after purchases. They should either use it for the purpose granted in the approval letter or change ownership after meeting the institutional criteria.”

The Metropolitan City repeatedly notified those who had not complied with this, but they refused to follow.

The criteria for building also vary according to the purpose. The Kathmandu Valley City Development Committee (currently Kathmandu Valley Development Authority) has a provision of maximum 80% ground coverage for construction of residential buildings in the Kathmandu Valley. For schools and colleges, it has a limit of 40% of ground coverage.

What’s more, residential buildings lack stairs for fire escape. Such stairs are needed in schools that are crowded. Imagine if students have to escape the building after a fire.

Ram Bahadur Thapa, head of Department of Physical Planning and Construction at the Kathmandu Metropolitan City, said though most private schools are being operated in residential buildings, officials were unable to stop it. “There are provisions to control it and we have also issued warnings. However, it is not a one-off incident, it’s very common.”

Bhaikaji Tiwari, Commissioner of Kathmandu Valley Development Authority, said, “We have laws in place, but they are not applicable. The official trying to implement it is likely to be chased away.”

Using legal loopholes

The government bodies responsible for approval for and monitoring of school buildings are not doing their job. Article 3 of Institutional School Criteria and Operation Directives 2012 by the Ministry of Education, says: “The institutional school building should be owned by itself or should have at least five years of rent agreement.” After the 2015 earthquake, the Institutional Schools’ Fee Determination Criteria Directive also endorsed the provision: “The school should have its building or land or at least five years of rent agreement.”

Regulatory bodies point to this provision for lack of regulation. Nandalal Paudel, head of Education Development and Coordination Unit, said: “A new school is allowed to open if it presents a rent agreement of five years. The provision may be favorable to the school board, but it is against students’ safety.”

However, even requirements such as size of classroom, open space, playground and standards haven’t been implemented. The regulation requires a new school to have its own building five years later or a plan to own land or building and the process of procurement should be cleared in the investment of the school. While the directives are being implemented, the schools should be completed within three years, and if the criteria set by the authorities are not met by 6 months, the school should merge with another or start the process of closing, announcing its move 15 days before the start of academic session. Bu these provisions have yet to be fully implemented.

On July 1, 2016, a wall of Pushpaanjali Boarding School in Badeguan, Lalitpur collapsed, which left two students dead. Some 17 students of grade 3 and 8 were injured. Following the incident, issues surrounding student safety, building code and monitoring were raised, but soon it was forgotten.

Govt schools no different

According to the Education and Human Resource Development Center, 39,70,000 students are enrolled in primary schools (1-5 grades) across the country. If 18,66,000 students of the lower secondary level (6-8 grades) are included the number reaches 58 ,36000. Out of these, 48,66,000 children are enrolled in government schools.

Among the 9,70,000 students at secondary level (9 -10 grade), 7,90,000 students and 4,28,000 high school students from 5,84,000 study at government schools. That means, 6.63 million students are studying at government schools.

What’s the state of government school buildings? “In the past, education started from traditional institutions such as Gurukul and Ashram. Then, communities started to fund,” said Deepak Sharma, a spokesperson of the Education and Human Resource Development Center. “Such school buildings did not follow engineering process.”

It can be deduced from Sharma’s statement that most government school buildings lack engineering design. Many schools are running in temporary buildings. The government has built two-room concrete buildings for some schools, but they are not sufficient. According to Sharma, the government is responsible for teacher’s salaries and curriculum, but not the buildings. Local government and donor organizations have been helping in building construction but it’s not enough.

Some government schools in Kathmandu, on the other hand, are seeking permission to add a floor to their retrofitted’ building. “What happens if new floors are added to the earthquake damaged and retrofitted buildings?” asked Nandalal Paudel, head of Education Development and Coordination Unit, Kathmandu, “No one is serious about the safety of student.”

Child Development Centers also operate in the same government schools. The number of government child development centers, and the pre-schools across the country number at 35,510, where 9,58,127 children are studying.

Until a year ago, a three-story building in Shantikunj of Tilottama Municipality-2 in Rupandehi housed Olive Restaurant. Some 33 students at the pre-school named Shishu Kalyan Montesari operated by Dipendra Nepal.

Accidents waiting to happen

The responsibility for monitoring whether school buildings are safe has been transferred to the local government from District Education Offices under Education Ministry. However, the question of safety remains. According to an officer of the Education and Human Resource Development Center, lessons have not been learned after the 2015 earthquake. “The situation is still the same. Forget earthquake, even fire or for some other reason, if students run helter-skelter all over the school buildings, it could cause a huge accident,” he said.

A six-story building of Deepjyoti School in Gongabu on the banks of Bishnumati River collapsed from the foundation after the 2015 earthquake. The 400 students enrolled from grade 1 to 6 classes were saved because it was a Saturday. Upendra Adhikari, who built it for residential purpose 10 years ago, runs the school. It could not withstand the load of school. The building was built on a weaker ground on the banks of the river.

A video of a building collapsing during the 2015 quake went viral o social media platforms. Morgan College had rented the building at Tokha Municipality-10, Kathmandu. More than 400 students study Engineering, Hotel Management and the BBA in the college. Bina Shrestha (KC) had obtained an approval to build a five-story residential building in 2010 from Tokha Municipality.

The dismal state of school buildings forces us to ponder a grave question: what if an earthquake similar to the 2015 quake strikes other than a Saturday?