Loose laws, illiteracy and poverty, along with an unsuspicious welcome of foreigners, have turned Nepal into a haven for Western paedophiles.

Janakraj Sapkota : Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Peter Dalglish’s residence in Kavre

On the afternoon of July 8, there was a commotion outside the usually quiet white brick-and-cement Kavre District Court. The presence of two high-ranking diplomats at a court hearing was unheard of. The Canadian Embassy in New Delhi had written a diplomatic note to the Nepal government to help Amanda Strohan, Chargé d’affaires at the Delhi-based Canadian Embassy, and counsellor Veronique Deshaies attend the hearing of Peter Dalglish, a Canadian aid worker and “humanitarian” facing trial for paedophilia.

Dalglish wasn’t just any foreign national. He was a former UN official who had served as country representative at UN Habitat Afghanistan and had received the Order of Canada, one of the country’s highest civilian honours. Dalglish had co-founded Street Kids International in 1988, to “work for conflict victims and street children”, and was appointed as chief technical advisor under the UN Child Labour Programme, in 2002. Through Street Kids International, Dalglish had been working for years in Nepal with vulnerable children.

The hearing took place a little over a year after Dalglish was arrested from his house in Kavre–with two children, aged 12 and 14–by the Nepal Police’s Central Investigation Bureau. Despite denying all allegations, he was found guilty of paedophilia and sentenced to nine years in prison by the court that day.

Dalglish’s might have been a high-profile case but it was hardly singular. This was just one in a series of incidents where foreign nationals, often masquerading as aid workers and champions of children’s rights, have been found abusing Nepali children. According to organisations working for child rights, loose laws, illiteracy and poverty, along with an environment where locals are welcoming of foreigners, have increasingly turned Nepal into a haven for paedophiles.

According to Nepal Police, last year alone, they arrested seven individuals—one Nepali and six foreign nationals, including three French, one Dutch, one American and one Indian–on charges of paedophilia. Police officials say at least 25 children were rescued last year and given psycho-social counseling. The year before, in 2017, 12 foreign nationals and two Nepalis had been arrested on charges of paedophilia.

“Paedophiles are increasingly active in Nepal’s schools, orphanages and childcare homes, taking advantage of poverty, illiteracy and the tendency of Nepalis to become friendly with foreign nationals,” said Assistant Inspector General Pushkar Karki, who is currently with the Central Investigation Bureau and is investigating nearly a dozen child abuse cases.

Although the police are working actively to investigate and prevent child abuse, the country’s crime investigation and judicial processes both have structural weaknesses, which are leading international paedophilies to target Nepal and Nepali children, according to Lori Handrahan, a veteran humanitarian worker who has carried out sexual abuse reviews for the United Nations.

Crimes in Nepal, punished abroad

Although paedophiles are believed to have been operating in Nepal for decades, many of the earliest cases involving foreign nationals were not prosecuted in the country. A lack of proper laws and a lack of awareness in law enforcement regarding the nature of such crimes led to many paedophiles fleeing Nepal before they could be arrested and prosecuted here. However, in a number of instances, the paedophiles were arrested and tried in their home countries.

In 1998, local residents in Chhauni had complained about the activities of Jean-Jacques Hayes, a French national who was associated with an orphanage called the Association for the Children of Chhauni. He was allegedly abusing a ninth-grader from the Panchakanya Secondary School who was living at the orphanage.

Hayes was arrested after organisations working for child rights, such as CWIN, Sathi and Voice of Children, filed a joint police complaint. A case was registered at the Kathmandu District Court, but Hayes fled to France the moment he was released on bail.

After learning of Hayes’ escape, Krishna Thapa, the chair of Voice of Children, communicated with the French organisation, Infant and Development, and with its help, filed a case at the Paris High Court. French police arrested Hayes in 2001.

As the Paris Tribunal had called Hayes’ victims to France to testify, on September 12, 2003, Nepal’s Home Ministry asked the Foreign Affairs Ministry to permit the children to fly to Paris. Eight out of nine boys, between the ages of 15 and 19, arrived in France to give their testimonies. The Paris Tribunal ordered Hayes to not leave the country, but about five months later he disappeared. There were rumours that Hayes had escaped to Istanbul. Interpol, upon the French police’s request, issued a ‘red corner notice’ for Hayes’ arrest.

Following a tip-off, a Nepal Police team found Hayes hiding out in an Attarkhel house in Kathmandu. On investigation, police discovered that Hayes, who had fled nine years ago, had reentered Nepal via Istanbul using fraudulent documents. He was then sent back to France to stand trial.

The Tribunal once again called Nepali children to Paris for their statements, and in 2009, six Nepali boys went to France. Acting on their testimony, the court sentenced Hayes to 10 years in prison and mandated that the victimised children be paid amounts ranging from $5000 to $10,000 in compensation.

Ten years since that verdict, none of the victims have received compensation. Hayes has already sold all of his property, but according to French law, if the perpetrator is unable to provide compensation, the French government will step in. However, that law is only applicable to French citizens, so none of Hayes’ victims are eligible.

“I still have scars from those old incidents,” said one of Hayes’ victims. “I don’t want to recall them now.”

Hayes wasn’t the first paedophile to target Nepali children and he certainly wouldn’t be the last. In the early 2000s, a consensus had built online among paedophiles that Nepal was a relatively safe place for them to prey on children, according to police. Given Nepal’s laxness when it came to policing foreigners who came to Nepal to ostensibly volunteer at orphanages and homes for disabled or destitute children, paedophiles had a ready population of vulnerable children that they could victimise without fear of arrest or prosecution.

There are several other examples where foreigners have entered Nepal purportedly for volunteering and were punished abroad for sexually abusing Nepali children. According to the US Justice Department website, British citizen Simon Jasper McCarthy was sentenced to 30 years in jail for possessing sexual images and videos of Nepali children, and for sexually abusing them, about 12 years ago. The police confiscated over 400 pornographic videos and photographs from his laptop. He had filmed himself sexually abusing children as young as six years old.

In his court statement, McCarthy confessed that he had met three children during his time in Nepal, where he had worked to set up childcare shelters. Out of the three boys, two were identified as Nepali.

Fertile ground for paedophiles

In 2017, a report published by ThreatNix, an organisation working on cyber security, said that Nepal had become a centre for western paedophiles, many of whom came to Nepal like McCarthy and Hayes did—under the guise of ‘helping’ children.

“It is no secret that Nepal has been a hub for paedophiles for quite sometime now. Apart from predators visiting the country for child exploitation, Nepal has also garnered quite a reputation in child pornography forums in darknet, following screenshot shows paedophiles’ opinions in Nepal,” says the report.

“It is no secret that Nepal has been a hub for paedophiles for quite sometime now. Apart from predators visiting the country for child exploitation, Nepal has also garnered quite a reputation in child pornography forums in darknet, following screenshot shows paedophiles’ opinions in Nepal,” says the report.

The screenshot reads: “There are at least 602 child care homes housing 15,095 children in Nepal. Orphanages have turned into a Nepalese industry. There is rampant abuse and a great need for intervention. Many do not require adequate checks of their volunteers, leaving children open to abuse.”

“Moreover,” the report further reads, “there were not only discussions regarding Nepal, many child pornography materials from Nepal were also being distributed from these sites on the darknet. [S]ome Nepali users were also found to be actively distributing contents in these forums.”

On April 5, 2018, the Kathmandu Police arrested 32-year-old Wolf Price from his rented house in Bhakunde Chaur in Chandragiri Municipality. Police raided the house after receiving a tip-off from locals, who claimed that Price was involved in “suspicious activities”. The police confiscated marijuana, condoms and several sleep-inducing drugs. They also rescued three teenagers—two girls aged 19 and 12, and a boy of around 12.

Price, a California native, had been visiting Nepal for the past 12 years. According to the Immigration Department, he arrived in Nepal on a 30-day tourist visa on January 1, 2018. For his second time, Price came to Nepal on March 6, 2018, on a 90-day tourist visa.

In her statement to the police, the 12-year-old girl said that Price would send her and the two other children to run errands, buy cigarettes and alcohol. He would then molest them.

In its verdict of August 22, 2018, the Kathmandu District Court sentenced Price to four-months imprisonment and Rs3,000 fine for paedophilia, and a month in jail and a Rs2,000 fine for drug abuse. As Price had been taken into police custody on April 5, 2018, he served only one additional day in jail and was released on August 23, 2018. Price flew back to the US and the Home Ministry has decided, through a secretary-level meeting, to ban Price from entering Nepal for 10 years.

Price is not the only foreigner who’s been banned from entering Nepal due to child abuse convictions. On December 19, 2014, Canadian Fenwick MacIntosh was arrested for child abuse and sentenced to four years and two months in jail. Upon his release, he was banned from Nepal for seven years. Similarly, German Hans Jurgen Gustav was banned for seven years after being convicted on child abuse charges.

This year alone, there have been at least three police cases involving foreign paedophiles.

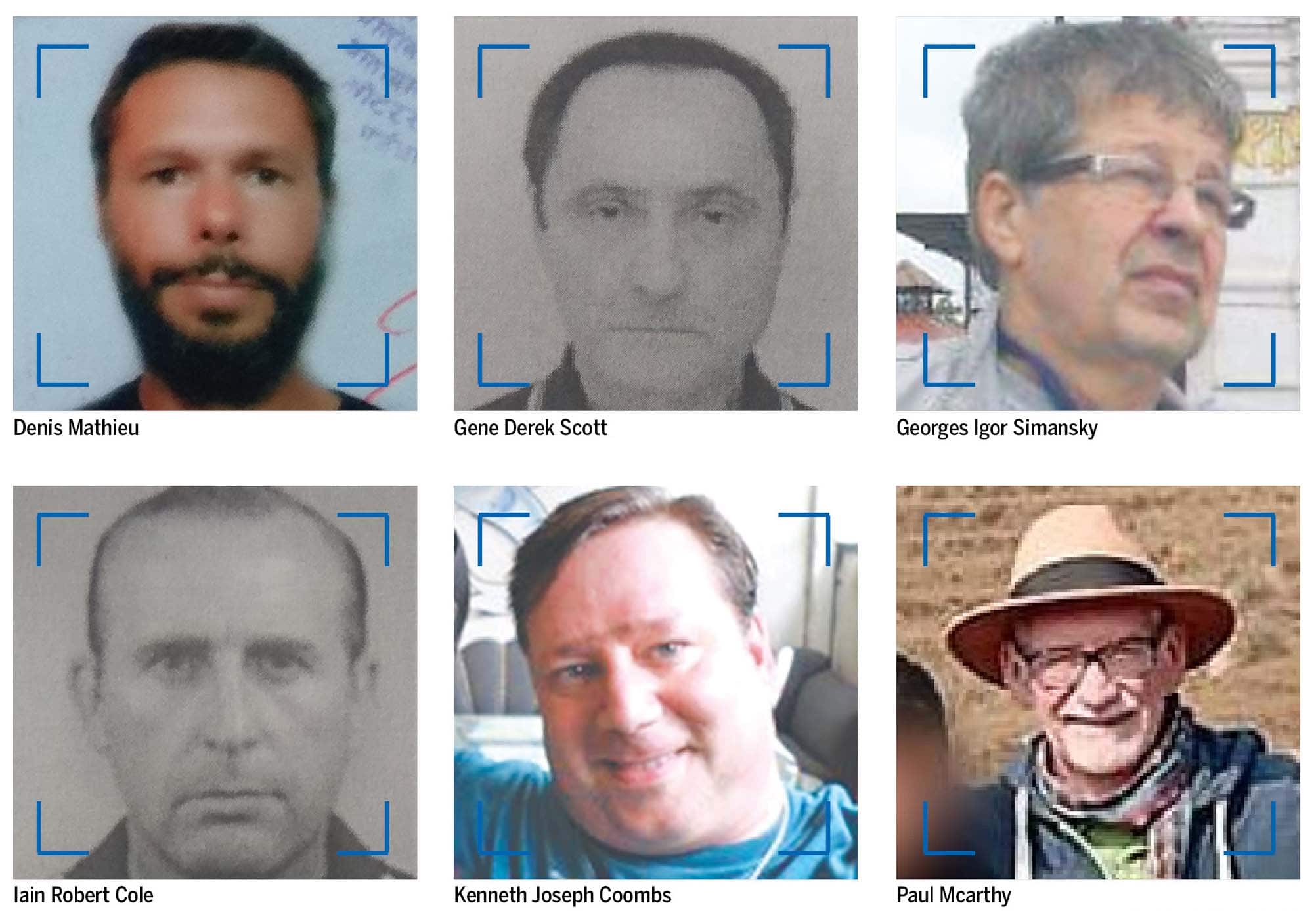

On January 4, police in Toronto arrested Paul McCarthy, a 62-year-old Canadian, from the Toronto Pearson International Airport for possession of child pornography. He was returning home after serving as a volunteer at a childcare home in Kathmandu. He was charged with sexually abusing five boys below 16 years of age. According to CBC News, all five boys were Nepali.

McCarthy was one of the donors of an NGO called Child Haven International, which operates several “shelter homes” in Nepal, Bangladesh, India and Tibet. According to the organisation’s website, he was associated with the NGO since 1992. The Canadian police haven’t disclosed whether the children he sexually abused were from the same shelter.

Before he was arrested, McCarthy’s visits to Nepal were becoming more frequent. According to Nepali immigration records, he came to Nepal three times since March 2017—the first time that month, a second time in September, and again in December. He then quickly returned to Nepal, days later, on January 1, and flew back to Toronto on January 8.

“We certainly never saw any signs or indication that he was that type of person and I hope he isn’t. I hope it’s a false allegation,” said Bonnie Cappuccino, international director for Child Haven.

On January 28, the Canadian Embassy in India informally notified Nepal Police’s Interpol Bureau about McCarthy’s arrest. Soon afterwards, the bureau sent an internal memo to acquire more details.

“He would take the students on tours, but we never heard about any cases of abuse,” said Prakash Nagarkoti, principal at the Gokarneshwor-based Green Tara Heaven School. “We have helped the Central Investigation Bureau and Ottawa Police by providing all the information we have.”

Then, on January 19, the Central Investigation Bureau arrested Iain Robert Cole, a 50-year-old British man, from his rented flat in Kalimati. Cole had arrived in Kathmandu with Gene Derek Scott and police discovered that both individuals had entered Nepal with the insidious motive of abusing children under the guise of helping them. Scott had already fled Nepal when police nabbed Cole.

Following the arrest, the police launched correspondence with the British Police to learn of Cole’s background. In a confidential notice sent by the National Crime Agency, the UK Police’s crime investigation wing, officers said both Cole and Scott had been under investigation for paedophilia allegations in the UK and that their crimes had spread from their home country through India to Nepal.

According to the UK Police, when investigating Cole’s Skype account, they had discovered suspicious correspondence with teenagers in Nepal that were “sexual and of a grooming nature”. The confidential notice sent to the Nepal Police has enough detail to cast doubt on the duo’s purported motive of helping Nepali children. Most intelligently, the notice states an incident where Cole was investigated by UK Police in 2017 for possessing pornographic photos of children. Cole was found guilty and given a suspended sentence. He was, however, placed on the UK sex offender’s register for 10 years.

After Cole was arrested in Kathmandu, the National Crime Agency raided his home in North-east London in the UK and confiscated 97 pieces of hardware, including cell phones, tablets, computers, hard drives and memory cards. In February, Cole was remanded into judicial custody by the Kathmandu District Court and is currently at the Central Jail.

An inability of police

Nepal Police officials themselves admit that previous laws were inadequate to deal with instances of child abuse at the hands of foreigners. This trend has escalated in recent years in Nepal after concerted efforts by countries in South Asia and South East Asia to combat child sexual abuse and the increasing practice of sex tourism, therefore pushing abusers into Nepal.

“Most paedophiles seem to make a shelter in Thailand and roam around Nepal, India, Sri Lanka and Vietnam, because these are countries with loose laws regarding child abuse. For them, these countries are fertile ground,” said Deputy Inspector General Mira Chaudhary, who was involved in a number of investigations on foreign paedophiles in Nepal.

Thailand formulated a strict anti-child abuse law in 1992. Since then, paedophiles from western countries began setting sights on vulnerable countries like Nepal. Cases have increased even more in Nepal, after India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Cambodia each formulated new laws regarding child abuse.

Many countries, including England and Australia, have strict laws regarding paedophilia. In 2003, the British government issued the Extra-territorial Legislation, Section 72 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 that allows the investigation of English nationals if they engage in paedophilia outside the country under ‘international jurisdiction’.

Geoffrey John Prigge, an Australian citizen who was sentenced in 2007 for molesting five Nepali boys, was charged under legislation that allows the Australian federal police to investigate Australians involved in serious crimes abroad and then prosecute them at home.

Since the early 2000s, when foreigners began to get arrested for cases of child sexual abuse, Nepal has attempted to draft robust laws in response. Article 225 of Nepal’s new criminal code, released in 2017, specifically addresses child sexual abuse: “Anyone who takes a child to a secluded place with the intent of rape, touches a child’s body parts inappropriately, or forces a child to touch or hold one’s body parts, or engages in any other inappropriate sexual behaviour shall be considered to have committed child sexual abuse.”

The criminal code mandates a three-year jail term and Rs30,000 in fines for anyone guilty of the above.

Article 66 (3) of Nepal’s Act Relating to Children 2018 also specifically addresses the many forms of child sexual abuse, including the showing of obscene material; creating any such material using a child; any kind of touching, holding or kissing with sexual intent; using a child to stimulate sexual excitement or sexual gratification; or using a child in sexual exploitation or for sexual services.

But according to Handrahan, who is also the author of Epidemic: America’s Trade in Child Rape, Nepal needs to take more stringent investigative measures if it wants to put a halt to western paedophiles turning the country into a hub for child rape and abuse.

“These almost exclusively white male Western predators apparently believe Nepal’s police, prosecutors and judges are poor, incompetent and corrupt,” said Handrahan, “and appear to be making a risk-calculation that Nepali investigators, prosecutors and judges earn small salaries, lack integrity and therefore can easily be ‘purchased’ by western predators who enjoy substantial inherited wealth, like Peter Dalglish, and/or much larger professional salaries.”

It is because of this inability to actively investigate and gather the evidence required for prosecution that paedophiles tend to avoid prosecution or are set free on minimal bail amounts.

At a recent programme held in the Capital, Judge Tek Bahadur Kunwar of the Patan High Court related how he had ruled that a Canadian citizen convicted of child abuse be forced to sell his property in Canada in order to pay compensation to his victim. He had even asked the Foreign Ministry for assistance in this regard. However, the Canadian appealed the decision at the Supreme Court, which upheld the seven-year jail term imposed by Kunwar but reduced the compensation due.

“Even though the accused was punished, the victim received little compensation and this too can make it difficult to control such incidents,” said Kunwar.

According to advocate Prawin Subedi, who has long pursued cases of child abuse, Nepal might have formulated laws regarding child sexual abuse but a lack of clarity remains. Victims, who are often as young as five, are asked to testify in court or provide statements to the police. However, as they are children, they are unable to clearly state the extent of the abuse or even how and when it happened. The police too have shortcomings, said Subedi, because they are unable to collect and present the evidence in time.

“There is a need for more clarity along with improvements to investigative and procedural processes,” said Subedi.

Given the increasing incidents of child abuse at the hands of foreigners, Nepal must prioritise combating these kinds of crimes, according to Handrahan.

“Nepal, as a society, and Nepal’s current government must make it a priority to fund and support an extremely well-staffed, expertly trained and well-funded Child Sexual Exploitation Cyber Crimes Unit that would include hundreds, if not thousands, of investigators trained in the use of the latest technology in this fight against child sex traffickers and predators,” said Handrahan. “Such a unit would also include thousands of prosecutors and judges trained in the latest legal strategies for prosecuting and sentencing these predators.”

According to Nepal Police spokesperson DIG Bishwa Raj Pokhrel, the police has recently been pursuing serious investigations into child abuse cases with the assistance of Interpol and agencies from other countries. It is collecting intelligence and presenting evidence in a much more systematic and diligent manner, said Pokhrel.

“We understand that Nepali children are at grave risk of child abuse,” said Pokhrel. “This is why the police are treating these cases with the utmost seriousness.”