The story of Western Tarai’s former kamaiyas who haven’t had a place to call home for 21 years even after being emancipated, reveals that neither the monarchy back then nor the local government now has done anything to improve their lives.

Unnati Chaudhary | CIJ, Nepal

This July 18 marks the 21st anniversary of the proclamation of the emancipation of the kamaiyas enslaved under a system remnant of slavery-related practices in the Western Tarai. After the government announced their emancipation on July 17, 2000, the former kamaiyas had converged on the highways and roads, which had been a place for protests demanding emancipation, and transformed it into a venue for a celebration.

Sixty-year-old Pradeshu Chaudhary of Kailari Rural Municipality-7, Kailali, participated in the celebrations. He was thrilled by the mere idea of living a life of his choosing in the open world, free from any form of oppression.

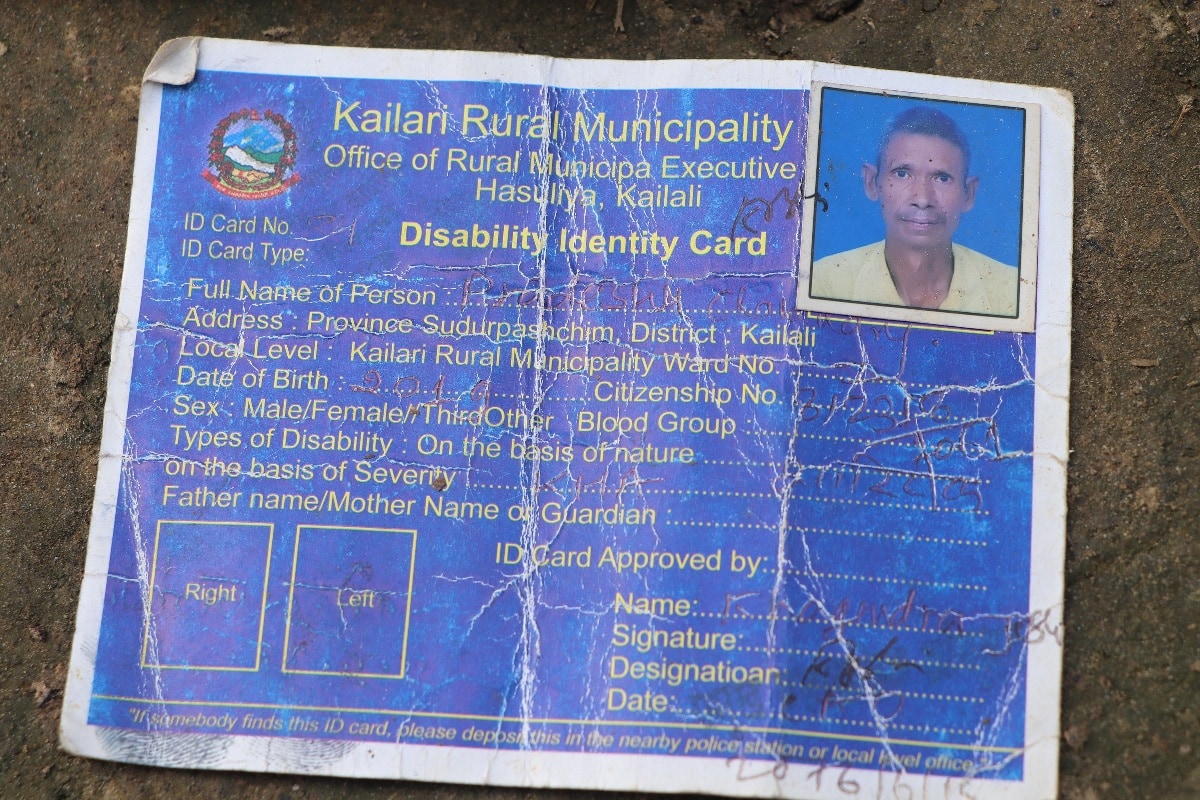

Pradeshu Chaudhary shows his kamaiya identity card. Photos: Unnati Chaudhary.

But, life did not go as planned. After receiving an identity card late, he stayed at the landlord’s house as he didn’t get any land to build a house on. Seven years after the declaration, an all-party meeting decided to resettle 62 families of freed kamaiyas in Milanpur of Kailari Rural Municipality- 7. Only then did he build a small hut and move there.

But, the grief didn’t end there. He didn’t get the title deed of the five katthas (0.08 acres) of the public land he got to use. Chaudhary has a blue identity card issued to freed kamaiyas. The government has given a blue card to the landless living on government or public land by listing them under category ‘B’. It is strange why a blue card was given to Chaudhary who had been living in a landlord’s house.

Born in the house of Ram Kumar, a landlord of Ramshikharjhala in Ghodaghodi Municipality, Chaudhary’s parents were also kamaiyas. After turning 15, he moved to Gyan Bahadur Karki’s house as a kamaiya. He was then diagnosed with polio.

Three years later, his father Dukhiram Dagoura died, and his mother also passed away soon. After his wife also left him, he married a mentally handicapped woman. With his new wife, he raised three sons and two daughters. The eldest daughter, Ashmita, is mentally handicapped. He hasn’t heard from Karan, the eldest son who went to India 14 years ago in search of work. The second son, who also went to work in India, has not returned. The youngest son, however, visits him sometimes.

The villagers help cultivate the land he lives on. He makes bamboo products at home to earn a living. “I can’t walk. I have to sell my products for as much as the buyer wants to pay,” says Chaudhary.

The story of gross neglect

The Kamaiya Labour (Prohibition) Rules consider those who don’t have a house or land in their name as category ‘A’ class freed kamaiyas who get a red card. Those who don’t own land but live in public or government land are given a blue card as category ‘B’ freed kamaiyas.

Those who have up to two katthas of land and a house in their name or the name of the family are recognised as category ‘C’ (yellow card) and those who have more than two katthas of land and a house are given a white card under category ‘D’. Chaudhary received the blue card according to these rules.

Milanpur is also home to 41-year-old Vishram Chaudhary who was born in the house of Narayan Chaudhary, a landlord of former Ratanpur VDC. His grandparents and her parents lived there as kamaiyas. Despite the declaration of liberation of kamaiyas in 2000, like Chaudhary, he remained in the house of his ‘malik’ until 2008.

Having received a red identity card, he wasn’t included in the rehabilitation programme. Without a land title deed, he can’t build a house. He is worried that he will be displaced again “Now we hear that our settlement lies in the Basanta corridor (protected area). We are being treated unfairly again,” said Vishram.

A total of 72 freed kamaiya families have been resettled in two settlements near Milanpur. There are 134 households in both these settlements. The land allotted to them isn’t cultivable and there are no irrigation facilities. There is a shortage of drinking water. There is one health volunteer for the entire settlement. When someone is sick, they have to be rushed to Dhangadhi or Tikapur, 40 kilometers away.

There is one school, where classes up to grade three are taught. The residents have to travel at least five kilometers to go to school. That is why the children here drop out of school.

We have demanded rehabilitation of freed kamaiyas, access to education for children, and provision of identity cards to freed kamaiya women. We have demanded a guarantee for our right to land and employment along with the provision of subsidies in social security, education, health, drinking water, and sanitation.

The Sapana kamaiya camp is not far from Milanpur. Khusiram and his wife Gorkhali live in this camp. They had been living in the house of Harishankar Thakur, a landlord of Dhangadhi for 25 years. However , they do not have an identity card. Gorkhali says, “The owner did not give us leave when the government was collecting information of the freed kamaiyas. We didn’t get an identity card. Authorities now accuse us of occupying a forest area.” Khushiram and Gorkhali freed kamaiyas not included in the official count.

Of the 46 households in Sapna camp, 40 haven’t received identity cards. According to Basanti Chaudhary, former president of kamaiya Pratha Unmulan Samaj, Kailali, an organisation that has been advocating for the issuance of identity cards to the freed kamaiyas, they have been deprived of identity cards due to lack of timely notification or their inability to take time off from work. She complained that no one listened to her repeated demands to provide identity cards and rehabilitate the freed kamaiyas.

Even the leaders of the kamaiya movement are deprived of identity cards. Sixty-year-old Sitaram Chaudhary, whose work was recognised by the then District Development Committee, is an example.

During the reign of King Gyanendra, Chhedalal Chaudhary was the chairman of Kailali District Development Committee. A meeting of the Freed Kamaiya Rehabilitation Committee chaired by Chheda Lal had decided to give 10 katthas of land to Sitaram as a reward along with an identity card after the rehabilitation work was completed. But, Sitaram has not even received the identity card of the freed kamaiya, let alone the reward.

Sitaram says, “The then district forest officer and others said that I am the leader of the kamaiyas and I would be rehabilitated. At first, I thought I would get the card and the land after everyone else does so, but I was treated unfairly.”

“Now we are being treated like non-citizens. When we visit a government office we see it is divided into women’s department, agriculture department, and education department. Which department should we free kamaiyas to go to lodge complaints?”

Sitaram was a kamaiya in the house of Thagu Pradhan of Urma VDC. Kamaiyas were paid 40 kg of paddy annually. After two years of working for Pradhan, he demanded 60 kg of paddy. After the landlord agreed, he worked there for 14 years. He tied the knot with Jokhni Dagora of Chaumala-1 in 1991 by taking a loan of Rs 9,000 from the landlord. The amount he owed the landlord had increased to Rs 32,000 after four years.

In 1994, the non-governmental organisation Lutheran World Federation conducted a kamaiya-targetted awareness programme. As a result, he sold his possessions and paid off his debts, and decided not to become a kamaiya. Sixty-three kamaiyas, including him, had emancipated themselves without a formal announcement from the government.

He then became a leader of the kamaiyas and embarked on a liberation campaign. Under his leadership, which established the kamaiya Abolition Society in 1996, seven kamaiyas of the former Gadaria VDC were emancipated after their loans of up to Rs 10,000 were waived.

Sitaram, who has been campaigning for the liberation of kamaiyas, is living on the public land in Pathari village in Dhangadhi Sub- metropolis -17. Having fought incessantly for others, he is now tired of having to fight for himself.

Local governments more indifferent to their suffering

When the emancipation of kamaiyas was announced in 2000, the government had said around 32,509 kamaiya families were living in Dang, Banke, Bardiya, Kailali, and Kanchanpur. Only 8,910 families were emancipated in Kailali. “About 5,000 of the freed families haven’t been rehabilitated yet,” said Basanti Chaudhary, former president of the Kamaiya Abolition Society.

Pradeshu Chaudhary’s house.

According to government figures, 15,570 families have received red cards, 12,000 blue cards, 1,869 yellow cards, and 3,070 white cards. As the government has made a policy to rehabilitate only those who have received red and blue cards, about 5,000 freed kamaiya families who have received yellow and white cards have been deprived of rehabilitation. However, the situation Pradeshu Chaudhary finds himself in shows that the actual numbers are much higher.

There are also a large number of freed kamaiyas not listed by the government and those that haven’t received any assistance to date. Identity cards of 800 freed kamaiyas left out in the count were issued in Bardiya, but they haven’t been distributed yet.

The rehabilitation of freed kamaiyas was being done through the District Land Reform Offices until 2015. However, that year, the government introduced a procedure to entrust the local governments with the responsibility. The understanding that the government at their doorsteps would look after them rekindled their hopes. However, the local governments have also not done any rehabilitation work.

We had high hopes for the local government, but it does not listen to us. We are still fighting for rehabilitation.

Dipu Chaudhary, a former member of the Freed kamaiya Rehabilitation Commission, says that the freed kamaiyas have faced more discrimination after the formation of the local governments.

The annual policy and program of the Sudurpaschim Provincial Government states that province shall continue collecting data and issuing identity cards to freed haliya, kamaiyas, and kamlahari families. However, progress has been slow.

Before the country adopted federalism, a separate budget was allocated in the name of freed kamaiyas. This was also stopped after the transfer of the responsibility to the local governments. When the land reform office worked at the district level, a revolving fund was also set up for the professional development of freed kamaiyas.

Later, the office was merged with the local government. Dipu Chaudhary says, “When the landlord arrives to inquire about the fund, he goes to the local level. When one goes to the district land revenue office asking about the fund, the person is sent to the local government. But the local governments say no such program exists.”

This year, the freed kamaiyas of Kanchanpur handed over memoranda to all nine local governments of the district and the provincial government after a budget was not allocated for programmes targetting freed kamaiyas. Ghasiram Rana, district president of the Freed kamaiya Society, says, “We have demanded the rehabilitation of freed kamaiyas, access to education for children, and the provision of identity cards for freed kamaiya women (Bukrahi). We have demanded a guarantee for the right to land and employment along with the provision of subsidy in social security, education, health, drinking water, and sanitation.”

According to Ram Prasad Rana, leader of the freed kamaiyas, the government’s disregard for rehabilitation continues even after the formation of the local governments. Ram Prasad says, “Now we are being treated like non-citizens. When we visit a government office we see it is divided into the women’s department, agriculture department, and education department. Which department should we free kamaiyas to go to to lodge complaints?”

Before the formation of the local government, freed kamaiyas, haliyas and kamlaharis could lodge their grievances at the Land Reform Office. Dipu says, “We had high hopes for the local government, but it does not listen to us. We are still fighting for rehabilitation. ”

Janak Raj Joshi, spokesperson for the Ministry of Land Management, Cooperatives, and Poverty Alleviation said that the rehabilitation work has been completed by the federal government and the remaining work has been handed over to the local government.

The then District Forest Officer and others said that I am the leader of the kamaiyas and I would be rehabilitated. At first, I thought I would get the card and the land after everyone else does so, but I was treated unfairly.

According to the ministry, a total of 300 freed kamaiya families are yet to be rehabilitated. Similarly, the ministry’s data shows that 4,750 families of freed kamaiyas are yet to receive grants to build houses. There are 1,279 such families in Kailali, 594 families in Kanchanpur, and 2,877 in Bardiya.

Almost every political party has been using the freed kamaiyas as their ‘vote banks’. All of them raise their issues, kindle hope but do not address them. Doesn’t the local government know about this situation of freed kamaiyas? When we asked the question to the chairman of Kailari Rural Municipality Lajuram Chaudhary, he says he is aware of the issue. Stating that the people’s representative of the local municipality had sent a list of kamaiyas excluded from the official list in five districts to the Ministry of Land Management, Cooperatives and Poverty Alleviation last year, he said, ” We have received information that the ministry has formed a task force to address the issues of kamaiyas left out in official counts.”

Millions in budget ‘frozen’

The Rs 20 million allocated to the Ministry of Land Management, Agriculture, and Cooperatives to prepare and implement programmes to uplift the freed kamaiyas was frozen after the ministry could not spend the money.

Local governments, on the other hand, are arguing that they have failed to work for freed kamaiyas as the federal governments hasn’t provided a budget for it. Kailari Rural Municipality Chairman Lajuram Chaudhary says that 85 kamaiya families are yet to be rehabilitated in his municipality, but the work could not be completed as the federal government didn’t allocate a budget for it. He says, “The government has not given any budget for the rehabilitation of kamaiyas to any municipality.”

kamaiya identity card.

Two years ago, the budget allocated to the rural municipality to provide grants to freed kamaiyas was frozen. Chairman Chaudhary argues that the budget was allocated on the last month of the fiscal year. He added that the freed kamaiyas refused to accept Rs 200,000 to buy land and Rs 100,000 to buy wood to build a house.

Chairman Chaudhary Kailari said that the rural municipality has already prepared the working procedure of ‘Janata Awas Program’ and through this program the problems of excluded kamaiyas and the extremely poor will be addressed. He said his government’s focus is on providing state support to 250 freed kamaiya families not included in the official count and 75 families that haven’t received any government assistance even though they have identity cards.

The government had decided to provide five katthas of land per family, 35 cubic feet of timber for building houses, and various skill-based training for self-reliance. However, even after 21 years, many freed kamaiyas don’t have the skills to earn their living.

NGOs including Base, Lutheran World Federation, Action Aid, Greens Nepal, kamaiya Abolition Society also spent a huge amount of money for the liberation of kamaiyas. However, the situation in Kailali shows that the freed kamaiyas have not reaped the benefits.

Back in 2000, Sher Bahadur Deuba was the prime minister who declared the emancipation of the kamaiyas. Twenty-one years later Deuba is back in power. The freed kamaiyas, who have been able to get a permanent shelter even for 21 years, hope that Deuba does something for them again.