The parties that lead protests and are champions of change give birth to new political narrative—this is the public perception. But this year’s local level election discontinued that notion and created a narrative of the supremacy of candidates.

Rameshwar Bohara |CIJ, Nepal

Late at night on September 6, the civil society leader Devendra Raj Pandey posted a poem on Twitter–titled ‘Raiti banna mann lagchha’, or I want to be a commoner–an excerpt of which reads:

The orders and directions of landlords accepted by generations

Let’s spread that message among the innocents

Let’s forget the oppressed, poor, deprived and development

Let’s follow our own traditional way

Some have pain, others suffering—what then?

Where in the world is there no inequality and injustice?

About it all, it feels futile to puzzle over

That’s why

I want to be a commoner.

The man expressing his satirical resentment against political parties is the very person who led the public uprising against King Gyanendra’s ‘royal coup’, a movement under which the parties were assimilated. The same movement put a leash on Gyanendra’s ambitions for an absolute reign. Nepal turned into a republic.

What might have stirred Pandey, who has reduced his public activity of late for reasons related to health and old age, late at night—that he expressed through poetry?

Pandey himself has termed it the “leaders’ waywardness”. His ire appears to aimed at the “drama” staged by parties ahead of the November 20 parliamentary elections. A drama where the parties are treating sovereign people as commoners. The way the modus operandi of the parties ahead of elections frustrated Pandey, that kind of experience is with the people for quite some time.

Balen Shah, mayor, Kathmandu metropolitan city. Pic: Amit Machamasi

The illustrations of this are campaigns like ‘No Not Again’ and ‘November 20—the day we segregate biodegradable and non-biodegradable waste’, both aimed at the top political leadership, that have been running for over a month and half. Another vivid example of this is the result of the May 13 local level elections.

This time, people in 13 local units voted independents to power. The fact that people chose independents in Kathmandu metropolis, three sub-metropolises and municipalities each and six rural municipalities boycotting big parties that had fought elections under an alliance was unexpected for many.

Upon witnessing the ‘miracle’ unleashed by Kathmandu mayor Balendra Shah, Dharan’s Harka Sampang Rai and Dhangadhi’s Gopal Hamal, all of whom cornered ‘heavyweight’ candidates, many voters have even argued that an alternative to political parties is being sought in Nepali politics. It is perhaps buoyed by that, there is a wave of people announcing independent candidacies ahead of the parliamentary elections.

Is it really that voters are beginning to project independents as alternatives to political parties? The question is becoming more pressing by the day. It’s because the voters seem to be harbouring an intense desire to punish the parties that take them for granted through the ballot box itself. Let us take a close look at the local level election results.

A wave of independents or of able candidates?

Not just in the urban areas with increasing middle-class, the independents shone even in the remote local units, from Jumla’s Chandannath and Kalikot’s Khadachakra to Bhojpur’s Salpasilichho and Baitadi’s Dilasain. Independent mayor of Mahottari’s Bardibas Municipality, Prahlad Kumar Chhetri, even got the panel of independents elected, including deputy mayor Taradevi Mahato and four ward chairs.

Ravi Lamichhane, President, Rastriya Swatantra Party, Hark Sampang Rai, mayor, Dharan sub-metropolitan city and Gopal Hamal, mayor, Dhangadhi sub-metropolitan city,

That as many as 50 ward chairs and about 300 ward members throughout the country got elected as independents is paltry in proportion to the total elected representatives. But a section of people frustrated with political parties and another section that takes an exception to the current political system has termed it a ‘wave of independents.’ Has the local election indicated such a wave in the offing?

Political scientist Hari Sharma considers it just an ‘urban phenomena.’ “This is not a search for an alternative to parties, it is a sign of the rejection of parties’ selection of candidates,” he says. “It can be understood as voters’ disenchantment with parties.”

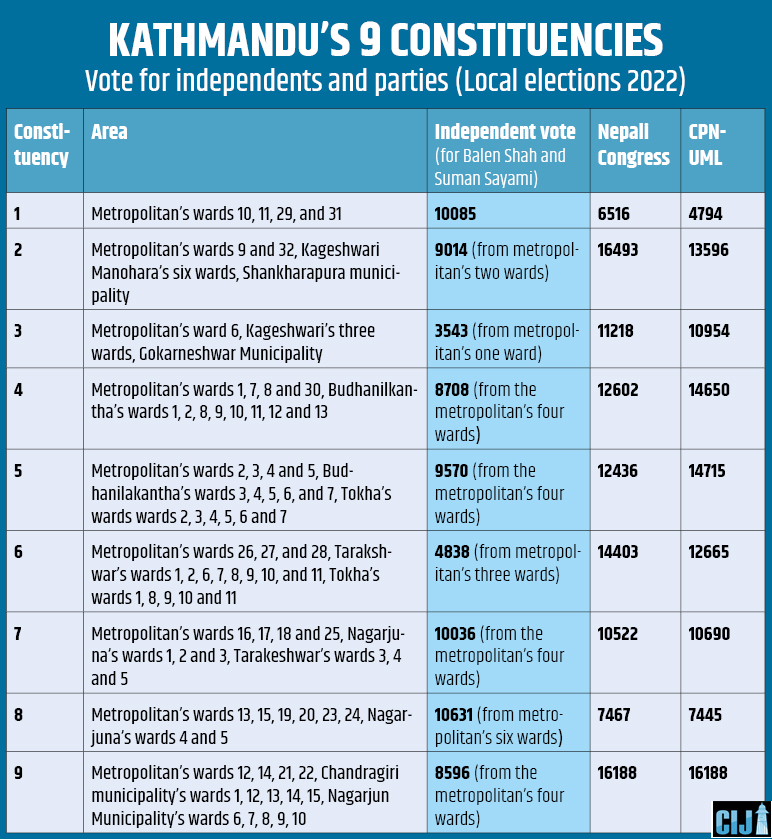

The effect of this psychology of voters can expand further in the upcoming election. For example, let us look at the votes garnered by independents Balen Shah and Suman Sayami in the local elections in Kathmandu. The total votes they received, 75,537, can be decisive in about six constituencies in Kathmandu in the upcoming parliamentary elections.

For instance, in Kathmandu Metropolitan City’s wards 10, 11, 29 and 31 that comprise the district’s constituency-1, Balen garnered 9674 votes and Suman Sayami 411. Nepali Congress’s Sirjana Singh and CPM-UML’s Keshav Sthapit got 6516 and 4794, respectively. If the trend of the local elections continues, the major parties would be limited to runner-ups.

Making up the district’s constituency-2 are the metropolitan’s wards 9 and 32, Kageshwari Manohara Municipality’s six wards and Shankharapura Municipality. Here, Balen got 8833 votes and Sayami 181 from just two wards. In all of these local units, Congress got a total 16493 votes and the UML 13596. In these constituencies, the ‘independent votes’ outside the metropolitan area is yet to be ascertained, so the impact is anyone’s guess.

Will the independent votes remain constant in the upcoming elections? Political analyst Nilambar Acharya argues the draw in the local elections was towards capable candidates rather than independents.

“If there was a wave for independents and against traditional parties, it wouldn’t be that Congress and UML would lose while the latter’s deputy mayoral candidate would win with maximum votes,” Acharya says. “This means the haunt is for able candidates.”

UML’s mayoral candidate Keshav Sthapit was synonymous with controversy. Congress’s Sirjana Singh was charged with benefitting from family legacy even from inside the party. These were some of the reasons behind their defeat.

Suresh Dhakal, an anthropologist who concludes that the parties lost because of their candidate’s deficiencies, has an even more interesting argument. He presented the example of Suman Sayami, who got 13770 votes. His family, an indigenous to Kathmandu, backs communist politics, particularly the UML. “If UML had fielded Suman and Congress Sushan Baidhya [who was widely discussed as a potential candidate], the result could’ve been different,” Dhakal says. “If UML had fielded Suman for mayor and Sunita Dangol for deputy, the party could’ve struck a clean sweep.”

Party alone won’t make you win elections

In cities like Kathmandu, Dharan, and Dhangadhi, Congress and UML were never considered weak forces before the local elections. That independents secured victories in those very cities hints to widespread dissatisfaction with the party-affiliated candidates, says Dhakal.

“It appears that the parties can win only if they field good candidates. One can’t win on the back of the party’s ideology and structure, one needs to be a good candidate,” he says. “On top of that, the parties were careless to an utmost extent while selecting candidates this time, which the voters rejected.”

Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba, UML President KP Oli, Maoist Center President Pushpa Kamal Dahal and CPN Samajwadi President Madhav Kumar Nepal.

Dhakal adds that even though it wouldn’t be prudent to consider the people rejected the parties altogether, it has definitely rung alarm bells.

An example of just how important the selection of candidates is the result of local elections at Pokhara metropolis and Hetauda sub-metropolis, where despite the party’s poor structure, CPN (Unified Socialist) emerged victorious. For the Unified Socialist which had recently split from the UML, there was no other option than to fall back on the alliance to contest at those cities that are considered the bastion of the UML. The party field the popular Dhararaj Acharya in Pokhara and Meena Lama, the former deputy mayor, in Hetauda. The result was both the candidates overcame the UML.

The UML was in pressure this time due to the electoral alliance of Congress, Maoist (Centre), Unified Socialist, Janata Samajbadi Party and Rastriya Janamorcha. While the party was cornered, it mayoral candidate at Ghorai submetropolis Narulal Chaudhary defeated the strong candidate from the Maoists Hemraj Sharma with a huge margin. In Dang’s Tulsipur submetropolis, the UML’s Tikaram Khadka overcame Congress’s Gehendra Giri, an experienced candidate. In Surkhet’s Birendranagar, UML’s Mohanmaya Dhakal defeated the alliance’s Upendra Khadka. The UML’s decision to field candidates that are popular among the people paid off.

There are many other examples where the decision to field candidates with good public image has drawn results. But in many local units, those who sought reelection faced defeat. For instance, Vijay Sarawagi, who defected from JSP to the UML ahead of the election, faced defeated by a huge margin. Nripa Wada, the Congress candidate who sought reelection as Dhangadhi mayor, faced a similar fate. Lal Kishor Sah, who sought reelection as Janakpur mayor, didn’t even come in second.

Meanwhile, some candidates saw tasteful wins for the second time. Chiribabu Maharjan, who was elected Lalitpur mayor last time by a close margin, secured an impressive victory, and so did Ghorahi’s Narulal Chaudhary.

In the local units, the candidates who tried to perform good duty in their tenure got a repeat win. They might not have been fully successful but they didn’t mess up. Those who did mess up, however, were discarded by the people.

Meena Lama, mayor, Hetauda sub-metropolitan city, Mohanmaya Dhakal, mayor, Birendranagar municipality, Surkhet and Dhanraj Acharya, mayor, Pokhara metropolitan city.

“The people weren’t satisfied with the local representatives, their work and service,” admits Bishnu Rijal, a UML central committee member. “Because the local governments were formed for the first time, there certainly were limitations but the people seemed to seek results. The voters have made that message clear.”

The elections also saw leaders who rebelled against their own party’s candidates-selection process. While in many places, those rebel candidates couldn’t make a dent, in others, they impacted the results. For instance, in Janakpur, Manoj Sah, who rebelled against the Congress, won the mayoral post. He had filed a separate candidacy after the alliance decided to award the ticket to Janata Samajbadi.

Bardibas’s Prahladkumar Chhetri was a similar case, rebelling against the Congress. In Chitwan, though he didn’t win, Congress leader Jagannath Poudel drew quite an attention after he filed a rebel candidacy.

In this election, factional politics, lucre and nepotism was dominant—this much the party’s own cadres revealed. Bhojaraj Pokharel, the former chief election commissioner, says, “Because of faulty candidate selection process, the trends of defection, not helping their own party and downright sabotage went up. The election got further expensive. That’s why, it seems necessary to go into primary election process to select candidates preferred by the people.”

If the parties had followed a system, they would put forward candidates preferred by the people, like Pokharel said. But the leadership appears hell-bent on selecting candidates that are loyal to them. This practice has been insititutionised at the cost of cornering the cadres.

This kind of irregularity rife in parties has also disturbed the composure of the candidates selected from grassroots level. The methods and party statute are being limited to paper. Let us look at a few examples.

At the central executive meeting of Nepali Congress in mid-July, general secretary Bishwa Prakash Sharma had proposed that the party selected candidates through an internal election among the active members for the upcoming polls. Arguing that the party conducted a ‘primary election’ as a pilot project, Sharma proposed an election among the active members to select 15 candidates for parliament and 30 for the National Assembly.

But the Congress leadership, not just the main leadership but also majority leaders, didn’t seem to be in favour of such a democratic practice. The result: while Congress candidates are being recommended, the role of active members is nowhere to be seen.

“The parties assumed that they were the only ones who created public opinion,” Dhakal, the anthropologist, says. “There is now a radical change from generations to technology but the candidate selection process of the parties doesn’t reflect that.” Dhakal, who believes that the parties have failed to understand the wind of change ultimately ceding ground to independents, argues parties have lost their sensibilities, and are detached from their ideology and structure. He says, “The parties have stooped so low that they cannot predict the direction the society is taking.”

Meanwhile, Mohammad Istiak Rai, a leader of the Janata Samajbadi Party, insists that since his party lost in many places because of wrong choice of candidates, it is now impossible to win elections on party’s backing. “The same is going to repeat in provincial and federal elections,” he says. “If candidates are not selected judiciously, then one can’t win elections just on the backing of the party of alliance. The people are going to teach a lesson.”

Election: there’s no meaning to excess spending

There is a big criticism levelled against the current election practice: ‘Election is too expensive, those without money can’t contest.’ Even those in full-time politics can’t ‘buy’ tickets for elections. A UML leader who despite receiving an election ticket returned it says, “I decided not to contest after realizing I needed to sell my house and lands to fight elections.”

With the situation such that to contest municipal elections, one has to spend tens of millions, there’s worry peaking that politics has gone to the grips of contractors, businesspeople and middlemen. But the local elections have also indicated a ‘silverline in the cloud’. While many local unit chiefs are saying they spent tens of millions to win election, Dharan’s mayor Harka Sampang Rai said, “I might have spent about Rs100,000 to 150,000 in the elections.”

Chiribabu Maharjan, mayor, Lalitpur Metropolitan City, Narulal Chaudhary, mayor, Ghorahi sub-metropolitan city, Nrip Wada, ex-mayor, Dhangadhi sub-metropolitan city and Vijay Saraogi, ex-mayor Birgunj metropolitan city.

Harka, who received financial support even from Nepalis abroad, has been charged that he didn’t make election spending public. But Harka’s campaign was such that his claim doesn’t look unfounded.

Kathmandu’s Balen Shah too performed a different exercise amid expensive elections. He has made public an election spending of Rs394,489.

Acharya, the political analyst, says that for capable candidates, a minimal expense is enough. “Harka’s and Balen’s campaigns showed that a steep expense alone might not amount to much,” Acharya said. “They utilized modern technology to the fullest, which even the poll commission and parties didn’t do.”

The reason behind the comments after the 2017 elections that politics is only for those with money and connections was the dominance of contractors and businesspeople in local units.

A study published then in Himal weekly showed that of the total elected local unit chiefs, over 11 percent were construction entrepreneurs, who were more of contractors than politicians. According to the Federation of Nepali Construction Entrepreneurs, in 2017, over 300 construction entrepreneurs had landed roles to lead local units.

So much so that nearly 43 percent of elected chiefs had no primary engagement in politics. Of which, some were active in real estate business amid the skyrocketing land prices of the last decade. The number of businesspeople elected to leadership is as much. Khimlal Devkota, an expert of federalism, says in 2017, almost one-thirds of elected representatives had a primary motive to earn money.

This time, a total of 203 construction entrepreneurs have been elected, of which 12 are mayors and 34 rural municipality chiefs. According to the Federation’s data, that number includes five deputy mayors, six deputy chiefs, 129 ward chairs, 14 ward members and two district coordination committee members.

Election alliance: hindrance to women leadership

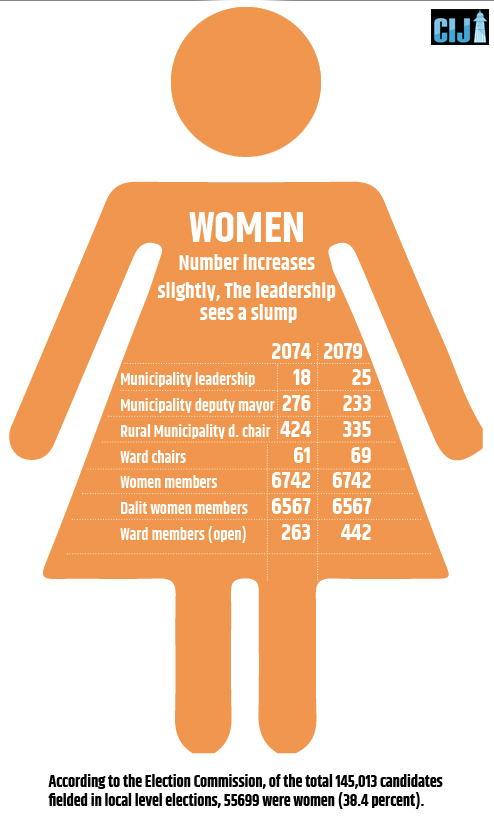

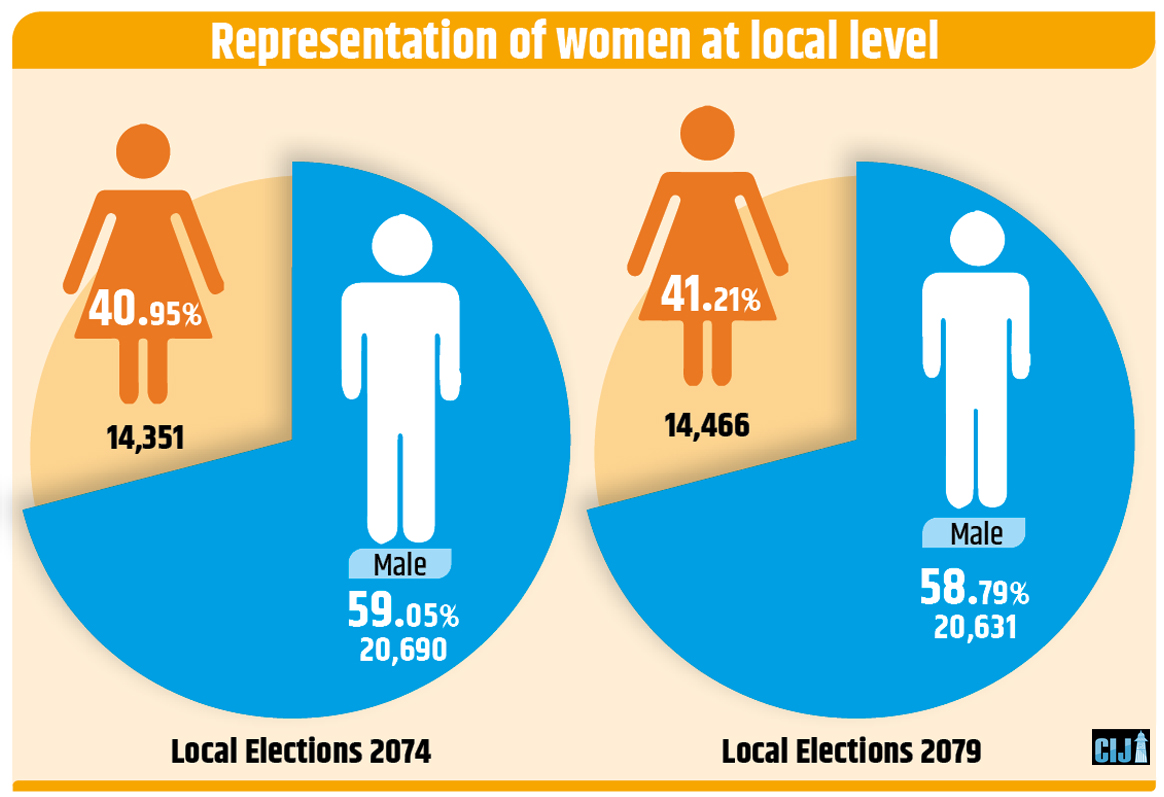

Perhaps the most exciting thing about the 2017 election was the presence of women representatives. Even though few women were elected to chief and executive positions, overall the presence of women in local governments was sizable. Of the total 35041 elected representatives then, 14351 were women. This time, of the total 35097 elected representatives, 14466 are women, or 42.21 percent. This points to progressive trend in the representation of women in local government.

In the last elections, 18 women were elected to lead the local units; this time, the number has climbed to 25. But the number of women deputy mayors has declined. According to the Election Commission, in the previous election, 276 municipality deputy mayors and 424 deputy chiefs were women. This time, the number has declined to 233 deputy mayors and 335 deputy chiefs. This is such a statistic that doesn’t give only one meaning. It also exposes the ‘inclusive face’ of the parties.

The local level election act has a provision to include at least one woman candidate for the post of mayor/ deputy mayor and chair/ deputy chair from a party. This time, by forging an alliance, the parties tricked that provision. By fielding the candidates for mayor/ chair and deputy mayor/ deputy chair from different parties, they took advantage of the legal loophole, and that shrunk women’s participation in the local governments.

This hindered women’s access to local leadership. If there were no such ‘syndicate’ from the alliance, there would be far more women candidates for leadership positions.

On the other hand, the number of chairs at wards considered important after the local unit chair/ mayor position has also grown by little. Meanwhile, the number of Dalit members at local units has increased slightly compared to 2017 elections. Even though the number of women ward members under open category is few, it’s still a rise from the previous election.

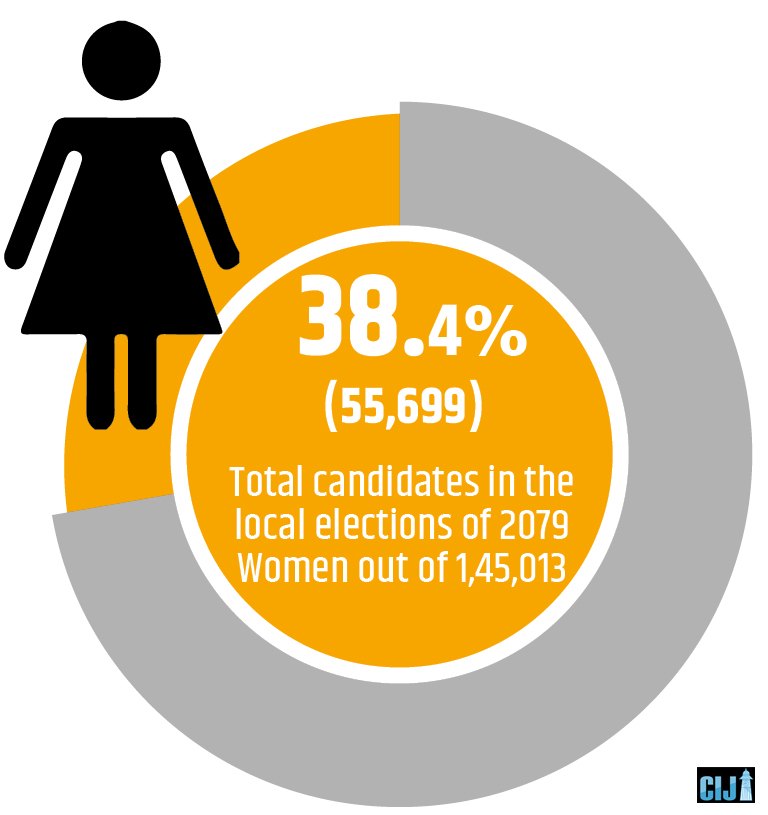

According to the Election Commission, of the total 145013 candidates in this local election, there were 55699 women, or 38.4 percent. “Even though the parties didn’t prioritise women, voters tried to elect them,” says Dinesh Thapaliya, the chief election commissioner.

This time, two rural municipalities and one municipality elected women in both the chair and deputy chair positions. In Jhapa’s Gaurigunj Rural Municipality, Congress’s Fulmati Rajbanshi and UML’s Poojana Neupane Kunwar were elected as chair and deputy chair, respectively.

In Dailekh’s Bhairabi Rural Municipality, Rita Shahi was elected as chair and Devi Bhandari as deputy. Both had fought elections with Nepali Congress tickets. In Kailali’s Lamkichuha Municipality, Congress’s Sushila Shahi and UML’s Juna Chaudhary were elected as mayor and deputy mayor, respectively.

Araniko Pandey, Shishir Khanal and Ranju Darshana announced their independent candidature.

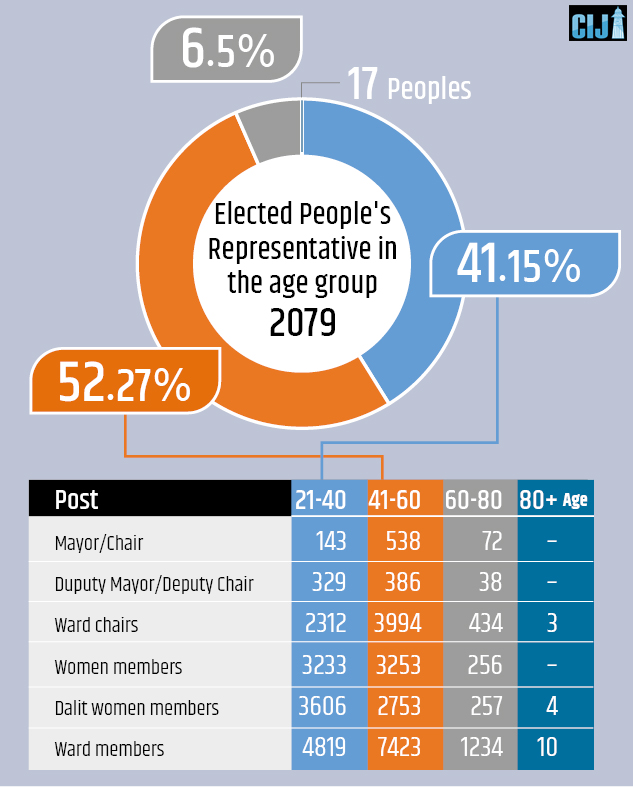

The narrative that ‘new faces in local government’ and ‘young faces in politics’ was established to some extent in the local elections. If we consider those under 40 as youths, as many as 14442 youths were elected in this local election. According to the statistics from the Election Commission, this is 41.15 percent of total representatives.

The highest number of representatives, however, are from the 41-60 age group—18347, which is 52.27 percent. The number of representatives in the age group 61-80 is 2291. There are 17 representatives in the age group above 80.

Political analyst Acharya says, “Winning is one thing, but many youths decided it was imperative they step up and filed their candidacies.”

The narrative of people in politics

The change of 1990 was such an incident that gave birth to many narratives about politics. The concept of local government was also born out of that movement. Even though there were village councils and city councils during the Panchayat era, the concept of decentralization of power from the centralized Singha Durbar also developed from the 1990’s movement. It was after that that local level elections started. After the Local Self-governance Act was promulgated, local units became stronger. And on that foundation, parties competed among themselves to introduce social security programs. The budget began to reach the target population.

Just when this exercise to take democratic practice and leadership to the grassroots level was getting mature, it took a hit from the Maoist violence. “I was then at Girijababu’s [then prime minister Girija Prasad Koirala] secretariat. We were aware of King Mahendra’s coup where he imprisoned all politicians. We were discussing how to move ahead to avert that kind of attack on democratic process. The concept of local levels was born out of that, as ways to avert such a possible crisis,” says Hari Sharma, the political scientist who was then an advisor to Koirala. “We predicted that if there were elected representatives in local units, imprisoning all of them would be beyond the King’s means.”

The first target of Maoist violence became the very local representatives serving their first term. To extend the violence’s impact, a campaign to ‘cleanse’ elected representatives was launched. On the other hand, King Gyanendra, who harboured plans to run absolute rule on the pretext of Maoist violence, turned local units without representatives. But even Gyanendra was not in the position to totally sideline local units, which is why he had to announce local elections in 2061BS. But after political parties boycotted that election, it was not endorsed by the people.

The Mass Movement of 2006 put a brake on both Gyanendra’s ambitions and Maoist violence. Even though the movement gave a new lease of life to the dissolved parliament, an all-party ‘syndicate’ became dominant after that. That hindered the arrival of people’s representatives on local levels. While the honchos of parties exercised an all-party mechanism to exploit state coffers, the local level elections were deferred until 15 years later.

It was then the class of contractors and middlemen was born, and with that, their capture of politics. That nexus gradually extended from local units to the centre. The bureaucracy only fueled it.

With the promulgation of the constitution in 2015, a narrative of the ‘end of political struggle and the need of strong leadership for economic prosperity through constitution implementation’ was established. ‘Nationalism’ was thrown into the mix. According to political scientist Hari Sharma, the politics of populism also became dominant and it targeted the basis of the constitutional course provided by the 2017 elections.

It is on this background that this year’s local elections were held. But what is the narrative established by this election? Krishna Pokharel, a professor of political science, has looked at it with two lenses—first, by limiting it to only local level elections. Second, by analysing it for its impact on politics hereon. “Through the elections, people reelected those who delivered. Those who didn’t deliver, parties and the candidates, were defeated. It is because it couldn’t deliver that the UML lost in Kathmandu and Dharan,” Pokharel says. “The alliance gave a partial result but as it neglected local concerns, it also boomeranged. Same thing happened in Janakpur. Pokhara showed that if the plan is thorough, one can win without a strong party base.”

According to professor Pokharel, the urban area has presented such a mood that if the voters are taken for granted, it can cost even big and strong parties dearly. The case study of this is Kathmandu’s mayoral candidate from UML Keshav Sthapit and many other candidates from big parties that tasted defeat in many other cities.

Will this ‘mood’ among voters get limited to last elections or will it continue through the parliamentary election and indicate the direction of politics hereon? Professor Pokharel says the local elections have presented a new narrative to drive the political course. “If voters are taken for granted anymore, it will backfire. While now it’s apparent in only urban settings, it can gradually become a national mood,” he says. “To avert that, parties need to select candidates judiciously. Otherwise, parties can prepare themselves for an unimaginable upheavel.”

And that kind of outlook is beginning to become apparent. In political scientist Hari Sharma’s opinion, the main risk of that kind of upheavel is connected to federalism. “The provincial structure only became a medium for political irregularities and rising expenses. A narrative is being created that it is not necessary for us,” Sharma says. “If we don’t exercise maximum diversity and inclusion in the upcoming election, especially in candidate selection, then it’ll be difficult for it to continue. The provincial structure is at risk from those who call themselves champions of federalism.”

On one hand, there is prediction that if parties don’t reform in terms of their modus operandi, and on the other, there is risk to federalism, which is considered the biggest achievement after the 2006 movement. What would be the potential context of the November 20 elections being held on this backdrop?

Let us look at a similar context from southern Europe. An article titled ‘The lost generation and its political discontents: as related divides in the southern Europe after the crisis’, published in South European Society and Politics journal, mentions the trend among the engaged, new-generation youths in south European countries (especially Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain) to be cynical of politicians, be less satisfied of democratic institutions, and a disinterest to get affiliated with established traditional parties and reluctance to vote for them.

Even if the context is slightly different, the disinterest among new generation youths here for established parties, their leadership and democratic institutions is almost similar. And Nepal is staring at a economic crisis, with the government not too keen to plan to avert that.