Even as the country has been reeling under an economic crisis, the local level election “brought a Dashain” to the commission at Bahadur Bhawan. A look into how financial irregularities is flourishing in state mechanism, making elections extortionately expensive.

Ramji Dahal |CIJ, Nepal

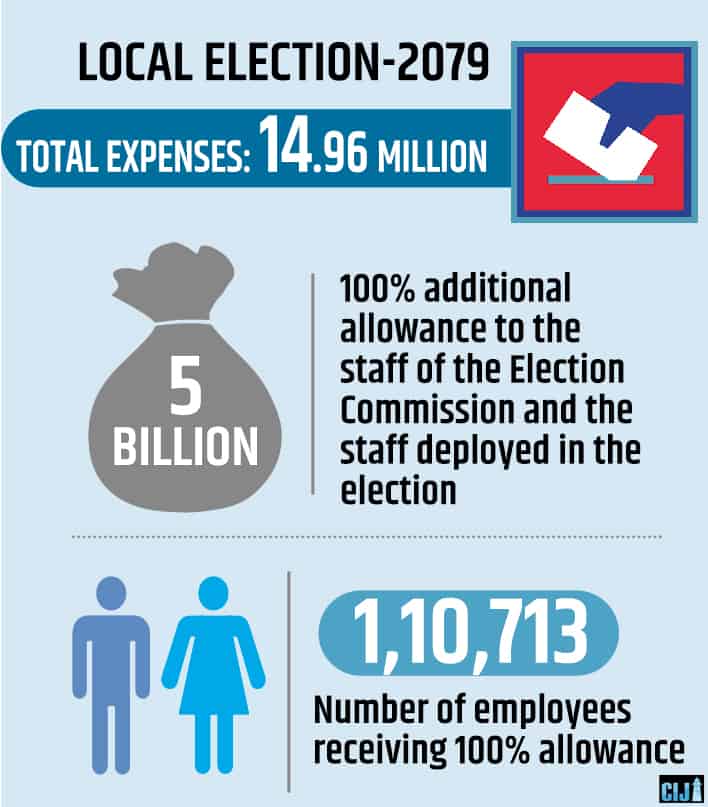

After the government on February 7 scheduled the local level election for May 13, office-bearers of the Election Commission decided to increase their allowances. In a March 14 meeting, commissioners and the chief commissioner decided to take a 100 percent additional allowance, arguing that ‘there will be extra work during the election’. Holding an election is the primary task of the commission and its officials. But they claimed an additional allowance just for carrying out that regular responsibility. Curiously, the commission makes such a decision ahead of every election.

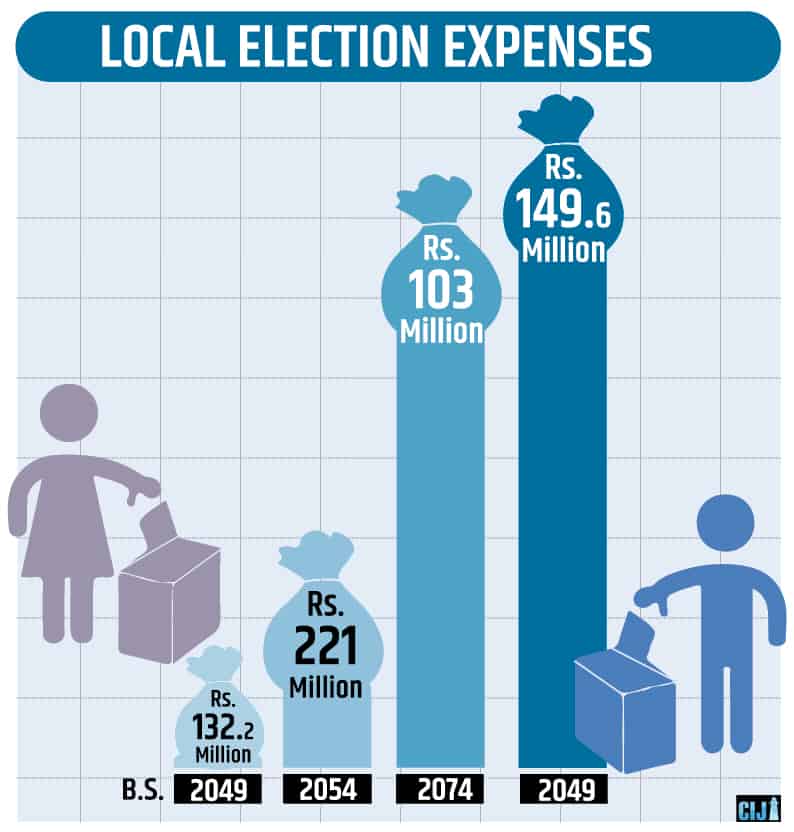

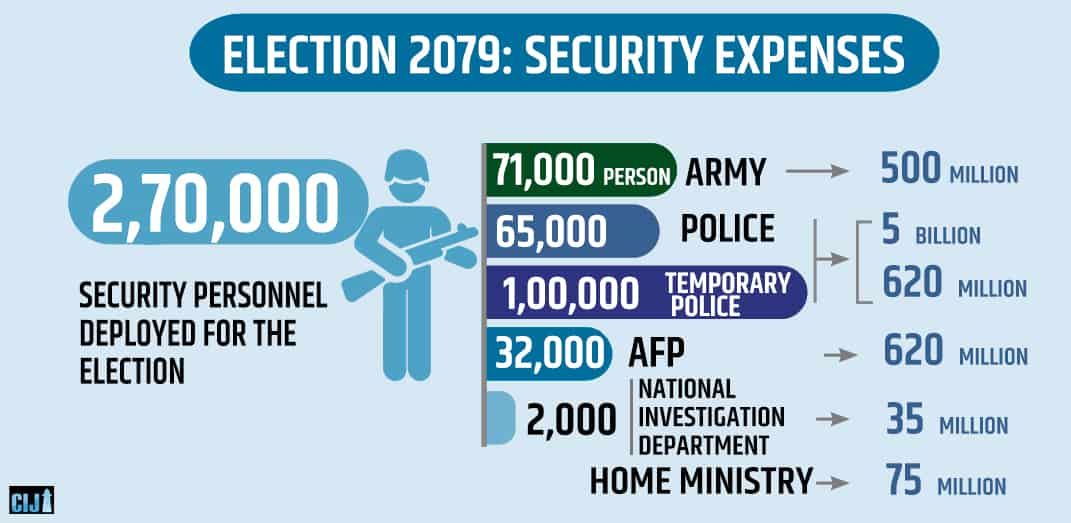

This decision has increased a Rs5 billion liability on the state coffers. Deeming that they would face a backlash if they only increased their allowance, the officials decided the same for all manpower deployed to organize the elections. As many as 109775 officials deployed in 21955 polling centers across the country were benefitted from the decision. The number reached 110713 incorporating election officers in all 753 local units and chief election officers in 77 districts. Besides the commission’s officials and office-bearers, 70000 Nepal Army and Nepal Police personnel each, 32000 APF personnel and 100000 temporary police were also deployed for the election.

Security personnel ferrying election material in Birgunj. Photo: Manish Poudel

Of the security personnel, the temporary police get 100 percent extra allowance for 40 days while the rest get that for four months. Other personnel, security and otherwise, deployed for temporary election works too were the beneficiaries of the extra allowance.

According to Bhupal Baral, secretary of the Ministry of Finance, the government had disbursed Rs8 billion 110 million to the election commission and Rs5 billion 620 million to the ministry of home (including expenses for temporary police). Besides that, the Finance Ministry disbursed Rs500 million to Nepal Army, and Rs 620 million and Rs50.5 million for APF and National Investigation Department, respectively. What is interesting is most of that amount would be used on the ‘cent percent extra allowance’ scheme. Confirming this, Surya Prasad Aryal, assistant spokesperson for the commission, said, “Rs5 billion 50 million of the total amount disbursed for the commission will be spent on human resource.”

Budget allocated for other agencies would also be spent for extra allowance. This is also an example of how far-reaching the consequences will be when the commission’s office-bearers decide to benefit themselves. “Is it right to take extra allowance while doing regular work?” questions Sushil Pyakurel, a rights activist. “It is an unethical practice, unbecoming of those working at a constitutional agency.”

Crisis in the country, ‘Dashain’ in the commission

The depletion of Nepal’s foreign exchange reserves amid liquidity crunch has been reported frequently in the media lately. To avert a possible crisis caused by its own poor policies and management, the government has put a ban on imports of various goods including vehicles. The executive also once adopted a five-day week rule, if only to repeal it later.

The splurge in the election amid deepening crisis in the country’s economy appears insensitive at best and foolhardy at worst. It definitely doesn’t sit well with the country’s financial reality.

A case in point: Aside from the extra allowance and regular communication expense facility, the officer-bearers of the commission decided to take further ‘communication allowance’—that included Rs2500 monthly for office-bearers, Rs2000 for the secretary, Rs1500 for assistant secretary and Rs1000 for deputy secretary of the commission. Meanwhile, election officers were provided with Rs5000 each for communication expense during the period.

Likewise, the commission decided to provide Rs2500 allowance to the election officers at each polling centers, Rs2000 to assistant election officer, Rs1600 to office assistants, and Rs1200 to other assistants and volunteers. This allowance is provided for at least 7 days. The deputy secretaries deployed as roaming supervisors in all 77 districts got Rs2500 per day, their drivers Rs1600, and Rs700-1200 was provided to officials participating election functions. In addition, the supervising team members also got Rs1600 each as lunch allowance.

This is the reason why, once elections are announced, officials compete to get transfers to reap the benefits. “Election season is like Dashain in the commission,” confesses Dr. Ayodhi Prasad Yadav, former chief election commissioner.

To begin with, the number of officials deployed for elections is too high, say experts. Why is that the case? “There is a pressure from political leadership to deploy officials,” Dr Yadav explains. “There’s a crowd of officials seeking transfers whenever there’s an election. Around 30 percent of officials deployed can be done away with.”

Many officials don’t even get a place to sit at saturated polling offices, Dr Yadav adds. So much so that, officials who contribute little to nothing to the election process are the beneficiaries of the extra allowance. According to Aryal, the assistant spokesperson at the commission, besides the cent percent allowance, officials working overtime get Rs300 as bonus.

Opaque purchase deals

The Election Commission purchased 58 types of goods for this year’s local elections (listed below). Unsurprisingly, the tradition of rushing to purchase them at the last hours continued this election too. Behind this are the shady deals with middlemen, often struck for exorbitant prices. “Those deals are made at a cost more than 10-20 percent from the usual rates,” Dr Yadav says. “The deals are struck without conscious thought.”

This election, the commission didn’t even estimate the amount of paper needed to prepare ballot papers. The papers were bought hastily after the election date was announced. The commission hasn’t yet released information on how much paper was used and how much cost was incurred to print them. Assistant spokesperson Poudel says Rs100million was spent on paper but he refused to reveal at what rate it was purchased. “Can the commission get away by simply stating the paper was purchased in haste, without revealing the cost?” questions rights activist Sushil Pyakurel. “Can a constitutional body be this opaque about spending taxpayers’ money?”

The commission printed a total 20 million ballot papers for a population of 17,733,723 in this year’s local elections (the number included 8,742,530 females, 8,992,010 males and 183 others). The papers were printed in the same fashion as in the 2017 elections. Back then, when the commission printed the same papers for parliamentary and local level elections, Sarbendra Nath Shukla, a Rastriya Janata Party leader, had filed a writ petition against the election governing body. After the top court issued an interim order, the commission printed separate ballot papers for the two elections. This is one among many examples of the commission’s inefficiency, leading to increased expense.

After the ballot papers were changed, other expenses too saw a rise. For instance, the election education material made with over Rs117million went to waste, according to the attorney general’s yearly report. The second lot of the material cost over Rs75.4million. Even then, citing the limited time to distribute those material, the commission didn’t send the material to 32 districts. “There is nobody to question the commission’s unnecessary expenses,” Lilamani Poudyal, former chief secretary of Nepal government, says. “The media too forgot its responsibility.”

The commission on November, 2017 purchased two digital color printers at the cost of Rs218 million and 340 thousand but the machines never did come into use. The attorney general’s report did raise a question about it. The commission replied that they would be used in the reelection of 2019 but that didn’t happen either. The commission had cited that it didn’t have the manpower to operate those machines and instead printed the ballot papers at Janak Siksha Samagri Limited at the cost of Rs216million and 709 thousand. The attorney general’s office has called this unnecessary expense as inappropriate.

For this year’s election, the commission insured chief commissioner and other officials down to office assistant against accidents at Rs two million each. The commission had struck a deal with the Rastriya Beema Sansthan on February 2022 to insure an altogether 110713 people. A total of 900 officials including the commission’s office-bearers, officials at its secretariat, and officials at provincial and district election offices were insured for 104 days; 6777 officials at the chief election officer’s office were insured for 70 days; 94000 at the election centres were insured for 15 days; and 9036 at the counting centres for 10 days.

The financial irregularity during the insurance process is interesting, too. For instance, in 2017, the commission provided contract to a company to insure 40754 officials at Rs200million and 785 thousand during the third phase of elections in Tarai, as mentioned in the attorney general’s report. By this, the cost of insurance per individual was Rs510.10. But if the commission had invited other bidders, it would have cost only Rs313.18 through competition. This increased the liability of state coffers by Rs102million 763thousand, according to the report.

Since the 2013 second constitutional assembly elections, the commission has made voter’s ID card with photograph compulsory. To take the Rs14 incurred to prepare one ID card in the last elections, there appears to be over Rs50 million expense to print the cards for the additional 3.6 million voters this time. But even those without the ID cards were allowed to vote this election; they just had to show a citizenship certificate or any identifying card stamped by government offices. Rights activist Sushil Pyakurel argues that if anyone with a citizenship is allowed to vote, it could slash a large amount of money to print voter’s ID card. “Why print a voter’s ID card if you allow voting with other cards?” he questions.

The office-bearers at the commission keep mum about these issues. Instead, they search for other ways to spend from state coffers. After retirement, however, they lay out a long list of irregularities in the commission. For instance, Dr Yadav, the ex-chief commissioner, says that he tried to reduce the splurge but to no avail. It was because, he says, the political leadership blindly accepts the bureaucracy’s proposals. But during the 2017 elections, Dr Yadav was committed to purchase high-end vehicles for all commissioners, including him. This despite the commissioners already had well-facilitated vehicles with them.

These irregularities highlight that there needs to be a debate on the commission’s structure. While India, which is considered the world’s largest democracy, only has three commissioners, including a chief commissioner, in its election commission, Nepal has six, including the chief. Professor Kapil Shrestha, a longtime observer of elections in Nepal, says, “If there’s only one attorney general, why are there five commissioners in the election commission?”

Looking for solutions

Now conversations are rife that the country cannot afford the skyrocketing election spending. It’s not just about the expense of the commission but also about expense done through security agencies, which is equally high.

Election material. Photo: Ramji Dahal

There will be parliamentary and provincial elections in a few months. And so, the debate about election spending will resurface. Can’t measures be adopted now to curb the spending? Experts say if the commission conducts regular election by making a calendar, spending can be curbed to some extent. Prof. Kapil Shrestha says that the commission now appears to be only an aide to the government that organizes election on the latter’s direction. “The commission’s function is to schedule elections, not just be the government’s aide.”

Rights activist Pyakurel says that if the commission follows a fixed calendar, there’ll be transparency in purchasing and that would curb spending. But it appears unlikely that office-bearers at the commission would be interested in such measures that would cut off kickbacks.

Another measure to cut back on spending, according to experts, is decentralizing. Even today, all the election management is done from Kathmandu’s Bahadur Bhawan. Former chief commissioner Bhojraj Pokharel argues that since local units have become capable themselves in many ways, they can collect voters list and manage election material, which can curb the spending. He advises that local units be made capable to print ballot papers, and keep the unused material for next election to avoid unnecessary expense.

Another reason why election spending is skyrocketing is security management. According to statistics, one significant chunk of security expense goes in managing temporary police. One section of critics say that the provision of temporary police should be ruled out altogether, because they are largely ceremonial. They argue the number of security personnel with all security agencies combined would be enough to hold elections safely.

Prof Shrestha says that temporary police that are deployed with nothing more than a baton have been long ineffective. “Police have been complaining they have a hard time to monitor temporary police instead,” said Shrestha. Pokharel too says that temporary police don’t have much of a role in election security. “Guns and batons can’t ensure election safety,” Pokharel said. “Election security is ensured by voters themselves. If the responsibility for security of polling booths are given to party’s representatives, it would make the main security mechanism further responsible.”

Pokharel further argues that if representatives from the parties are deployed as volunteers, it’d make parties responsible. He cites a successful example of this model in nearby Bihar state of India.

But Pokharel doesn’t sound optimistic that there will be cutback on spending with the commission’s existing structure and manpower. He concludes that there’s not much to be expected from a commission where officials believe they get salary just by checking in to the office and extra allowances for work.

There are examples that the financial irregularities in the commission have been fueled by the constitutional body itself. The commission, which appeared helpless in its responsibility to control candidates’ spending, stands as an irony given that there is excess spending inside itself. Not more than a week after the commission announced a bar for spending to candidates, Dr Shashank Koirala, the Nepali Congress leader, said in public that he had spent Rs60million in last elections, multiple times higher than the bar set by commission. But he had registered an amount of Rs2.175million election spending at the commission. While the commission asked for clarification with Dr Koirala, it didn’t do much further, satisfying itself with the sketchy reply Koirala furnished. It didn’t even feel it necessary to ask for further clarification.

The reason behind this is the office-bearers of the commission get scared to question the candidates while they themselves are spending in excess. They might ask for clarification but nothing more. Let alone any action. “They get into the commission with political force, and engage in embezzling state funds colluding with leaders—how would they have the moral strength to question their own masters?” said one former commissioner on condition of anonymity.

The Army too enters the fray

Photo: RSS

On April 12, President Bidya Devi Bhandari issued a permission for the government to deploy Nepal Army to ensure election security. After a meeting of the Central Security Committee passed the ‘Local Level Election Integrated Security Plan-2022’ and recommended the deployment of the Army in election, the government had forwarded the minute to the President on April 7.

The deployment of the Army in elections has continued since 1990. After the Khilraj Regmi-led interim government decided to take help of the Army during 2013’s second constitutional assembly election, the security agency has increased its role as well. It might now be hard to envision an election without the Army’s role, but the security agency has also extended its role to other sectors apart from election safety. For instance, the Army Secretariat lobbied with the Home Ministry to ferry election material to remote areas in its helicopter.

According to Army spokesperson Narayan Silwal, the expense of helicopter use is to be born by the commission.

Was it necessary to use the helicopter to transport election material and ballot boxes? Ex-chief secretary Poudyal says it was not, arguing that the material could’ve been transported in jeeps. He adds that helicopter use only increased unnecessary expense. “There was no need to use the Army’s helicopter since the ballot counting takes place in municipality headquarters,” Poudyal says.