The availability of fake rubber fingerprints in the Indian market along the Nepal border has led to many cases of fraud in the Terai districts. Even if there are piles of lawsuits in the courts, officials lack the means and the drive to look into and stop such crimes.

Sagar Chand and Man Bahadur Basnet |CIJ Nepal

Garuda Municipality lies 20 km south of Chandrapur in Rautahat district on the east-west highway. From Garuda Bazaar, a road leads east to Gaur, the district headquarters, passing through Malahi village in Ward No 3.

This is where Rajaram Sahni and his wife live with their two daughters in a two-room hut with a thatched roof. When we visited them last February, we found Rajaram napping in the yard. He was lying on a wooden plank with his chin propped up on his palm and his fingers covering his eyes.

“Is this Rajaram Sahni’s house?” He was startled by our voice.

Five years ago, a similar stranger had brought shocking news that had shattered the Sahni family’s life.

Rajaram Sahani, his wife, and their two daughters. Photo: Sagar Chand

It was noon on July 20, 2017. Rajaram was sitting under a tree in the yard to escape the scorching heat of the paddy fields. Suddenly, a stranger appeared before him.

The man, who was wearing a white shirt and blue pants, introduced himself as a staffer of a government office. He asked Rajaram if he was indeed Rajaram Sahni. When he got the confirmation, he took out an envelope from the black bag on his shoulder and handed it to Rajaram. He also made Rajaram sign the receipt of the letter after explaining it to him.

Rajaram, who barely knew how to read, asked him to read the letter aloud. He couldn’t comprehend most of the words written in legal jargon. But one word struck him like a bolt–a lawsuit. “The scoundrels have filed a case against us again!”

The letter from the District Court of Rautahat said that he was accused of taking a loan and not repaying it. The letter also summoned him to appear in the court within a given deadline. The plaintiff was Rajaram’s neighbour and relative, Trailok Chandra Sahni.

The next day, Rajaram hurried to the court and checked the case documents. A handwritten tamsuk (an informal promissory note) that he had borrowed 3.7 million rupees from Trilok Chandra on May 20, 2013 was presented as evidence. The note said that he would pay an interest of 10 percent and clear the entire debt by the second week of November. Rajaram, who was sued for failing to pay back the loan and interest as per the note four years ago, was shocked by the court’s notice.

After the lawsuit, the land office froze 0.25 acre of land owned by this family, as per the order of April 24, 2019. Out of this land, 0.17 acre is arable, while the remaining 0.08 acre are roadside plots. According to the current market rate, the arable land is worth between 250,000 to 300,000 rupees per kattha (0.01 acre), and the roadside land is sold for 2.5 to 3 million rupees per kattha. “They filed the case to grab my land connected to a 32-feet wide road by submitting fake documents,” Rajaram says.

For six years, Rajaram has been fighting a legal battle over the loan he claims he never took. He told the court that Trailok Chandra had forged the promissory note, with his fingerprint on it. He maintained his innocence throughout the trial. However, on December 27, 2021, the district court ruled against him and ordered him to repay the loan.

The events that followed revealed an unusual and new form of deception by predatory lenders in Nepal’s Terai.

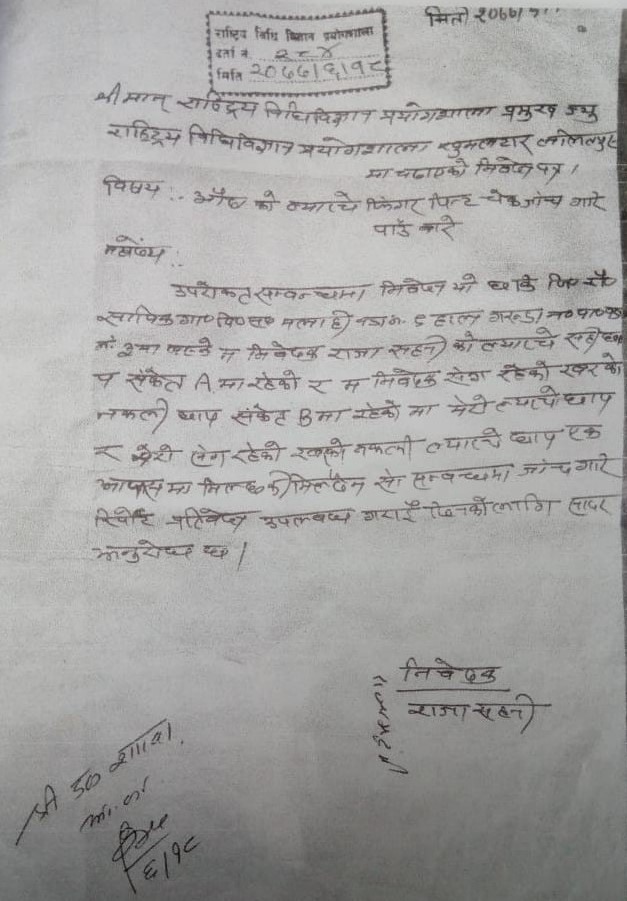

Rajaram disputed the validity of the fingerprint and requested a scientific test. On December 24, 2018, the Rautahat District Court directed the National Forensic Science Laboratory to compare the fingerprint on the tamsuk with Rajaram’s own fingerprint.

The laboratory received the court order, the tamsuk and Rajaram’s fingerprint sample on January 29 and sent its report on March 17, 2019. The report, reviewed by Piyushman Shakya, a scientific officer at the laboratory, stated that ‘the fingerprint sample provided by Rajaram in court and the fingerprint on the tamsuk have matching line quality’.

Paper made with fake thumb impression of Rajaram Sahni.

However, Rajaram was sceptical and decided to test the forensic science laboratory’s competence and integrity for a year. He made a fake (rubber) copy of his thumbprint at Bairagania, an Indian border town two kilometers from Gaur, for a thousand rupees. He knew that rubber fingerprints were available there.

On October 31, 2019, he visited the National Forensic Science Laboratory at Khumaltar in Lalitpur to distinguish between his real and fake fingerprints. Vasudev KC, another scientific officer at the laboratory, performed this test. The test report, prepared on the same day, showed that there was no difference between Rajaram’s rubber and real fingerprints.

Rajaram returned to Khumaltar on January 27, 2020 with a request for a re-examination after finding out that his fake and real fingerprints were identical. In his second petition, he asked for a thorough analysis that would answer whether the live and rubber fingerprints matched, whether they could be differentiated, whether they had the same line characteristics and whether they were distinct prints.

The test, conducted by Senior Scientific Officer Mukul Pradhan, showed that the rubber fingerprint matched the live fingerprint, but their natures did not match.

To confirm his findings, Rajaram applied for a third examination on October 4, 2020. The third test report, which was examined by KC, the scientific officer who tested his first application, stated that although the live and rubber fingerprints had matching line properties, the fake fingerprints had rubber characteristics. After this, he said that he was reassured that their laboratory could tell apart fake rubber fingerprints from real fingerprints.

“How can my fingerprint be on the tamsuk if I never took a loan from anyone?” Rajaram wonders. With this question in mind, he went to Rautahat District Police Office. He showed them his rubber finger print made in India and its test results as evidence.

At Rajaram’s request, the then District Police Chief SP Siddhivikram Shah personally contacted DSP Udayajung Rana from the Central Forensic Science Laboratory of the police to investigate. “DSP Saab said that a rubber fingerprint was put on the tamsuk after checking it,” Rajaram said.

SP Shah, who is now the head of District Police Complex Lalitpur after a promotion, says, “I called DSP Rana informally and asked him to check. He said that the fingerprint was fake.” He says that it was hard to investigate further because the police could not access the full case file in court without arresting the suspect.

Shah says that he wanted to have the fingerprints verified in India. However, he says that he could not start the investigation because of the legal deadline of filing a case in court within 24 days of arresting the suspect. “The process of sending to India is long. We have to coordinate with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs through the Police Headquarters,” he says, “It was not possible within 24 days.”

He says that even in an informal conversation, the judges declined to give him the full tamsuk file. They said that it would set a bad precedent to give the police a file of a case that was still in court. “So I advised the victim to file an application in court to have the fingerprints tested again,” SSP Shah remembers, “I told him what to do since I could not investigate even though I wanted to.”

Rajaram’s request for a third round of fingerprint verification.

Following Shah’s advice, Rajaram petitioned the court to verify the fingerprints. On January 31, 2021, the Rautahat District Court sent the tamsuk’s fingerprints and Rajaram’s fingerprints to the forensic laboratory for another examination. The Forensic Science Laboratory formed a three-member panel under the coordination of Mukul Pradhan, Senior Scientific Officer of the Bardibas branch office. DSP Udayajung Rana from the Central Police Forensic Science Laboratory in Samakhusi, Kathmandu and Line and Accounts Expert Vishwaraj Poudel were panel members. Two of the three panel members had previously examined Rajaram’s rubber and real fingerprints.

But the test report from the panel on October 20, 2021 was shocking. The same laboratory had differentiated between the real and fake fingerprints from the samples that Rajaram had personally provided. But in the test report from the panel, it stated that the laboratory could not give a definitive opinion on whether the print on the tamsuk was a rubber fingerprint or not.

The panel said that they lacked the necessary research and training as well as sufficient books from the relevant organisations to scan the fingerprints on the disputed document to determine whether a rubber fingerprint was used on the tamsuk or not. The report also said that there were only five fingerprints on the document without a single signature.

The report also stated that ‘Although the line patterns of the tamsuk’s fingerprint and the sample fingerprint (Rajaram’s) are similar, it is not possible to determine if the person himself gave the fingerprints on the tamsuk or not’.

Despite the panel’s inconclusive report, Judge Keshav Kumar Pandey delivered his verdict. He found Rajaram guilty and said that he could not reject Mukul Pradhan’s report from three years ago, which was clear and strong. According to his verdict, Rajaram had to pay 4.83 million rupees as principal and interest on the loan. Rajaram appealed this decision from the district court, which came on December 27, 2021, at the Birgunj High Court. The case is still sub-judice.

A flawed test

People can be biased. But physical evidence is supposed to be impartial, and that is a fundamental assumption and expectation of the criminal justice system. Laboratory tests are also physical evidence.

In Rajaram’s case, however, there were contradictions and confusions in the laboratory during his trial. On one hand, the forensic science laboratory said that it could not tell if the fingerprints were given by a living person or not. On the other hand, there were frequent visits by Arvind Jha, who claimed to have lent money to Rajaram, after the court ordered an examination of the documents.

The records show that Jha met with scientific officer Piyushman Shakya several times at the laboratory. On February 26, 2019, Jha and another person went to see Shakya at 2:40 pm, according to the laboratory’s registration book. On March 17, Jha and two other people arrived at the laboratory at 1:35 pm to meet Shakya.

Shakya was the scientific officer who examined Rajaram’s disputed document. It is noteworthy that on March 17, Shakya prepared a test report of this document, which showed a fingerprint match. Rajaram was not satisfied with this result and asked for a re-test. The laboratory could not give a definitive opinion in the second test. Before that, DSP Rana from the Central Forensic Science Laboratory had unofficially declared that the document was fake

Centre of fraud

Ramaishwar Sahni from Sarlahi Balara-2 sells fish by cycling around different villages. His business has suffered greatly for the past two years because of a case filed against his 60-year-old mother Malbhogia Kumari by an unknown person.

The charge sheet said that on February 15, 2073 (2016), Malbhogia borrowed 24,380 US dollars from Naresh Kumar Sahni from Gaur in Rautahat. It said that if she did not pay a 10 percent interest rate after one and a half months, i.e. by mid-March, then the lender would seize her property.

Test report provided by the national forensic science lab.

Malbhogia’s family said that they did not know either the borrower or the lender. But Naresh Kumar sued them on September 27, 2021 for not paying back the loan as per their agreement and showed a tamsuk as proof. This family was devastated by this debt.

Malbhogia only learned about this loan when she received a letter from the court about the case. She understood from this document that she had to appear in court within 21 days. It was dated January 19, 2022. She went to see the document with her husband and son after getting this letter. “Mother told them that she never took any money or gave any fingerprints,” her son Ramishwar said, “Then I asked her to tell this to the judge. The first people we saw were staff members.”

Ramaishwar Sahni thinks that someone may have used his mother’s fingerprints with a ‘digital scan’ technology. He said, “We didn’t know Naresh when we saw him at Ratnapark in Kathmandu in March with another victim of this scam. How can someone who doesn’t know you lend you money? It makes no sense!” The charge sheet said that Naresh was from Gaur Municipality in Rautahat.

The family hired a lawyer after this case. The lawyer presented Malvogia’s plight to the bench. On July 5, 2022, Judge Kazi Bahadur Rai ordered a laboratory test of the document. The court sent it to the National Forensic Science Laboratory for testing on July 24. But six months later, the laboratory wrote back to the court that it was unclear and asked for a sample by ‘rolling method’. The test report of this new sample, which was sent to the laboratory on March 6, said that Malbhogia’s fingerprint didn’t match with the tamsuk’s fingerprint

Naresh quickly filed a petition to drop the case when the report did not support him. Judge Babukazi Baniyan’s bench agreed to withdraw the case on June 12, 2023. “They dropped the case after the report went against them. Mother was very happy,” Ramishwar said on the phone. But he did not sound happy himself. He said that he wanted to sue those who made them suffer so much. “We won the case. But it was very painful,” Ramishwar sighed.

The court had frozen the Ramaishwar family’s small property since the case started. “The scammers tried to take our land,” Ramaishwar said, “We lived in fear for two years that they would evict us.” He is planning to file a case against them.

Many people in Terai districts face a common problem. They borrow money from lenders who document a higher amount than the actual loan, charge high interest rates or seize their movable assets if they fail to pay. Last February/March, some victims from Madhesh Province and Lumbini Province walked to Kathmandu and demanded justice. They said that the loan sharks were too cruel and powerful to stop.

Ramishwor sahani and Rajaram sahani.

The government set up an inquiry commission last April to help the loan shark victims after they protested for months in the federal capital. The commission was led by Gauri Bahadur Karki, a former chairman of the special court. A total of 24,000 victims applied to the commission. Most of them came from Madhesh province. The District Administration Office Rautahat received 2,078 complaints. This was the fifth highest number among the districts in Madhesh province. The highest number was 3,322.

How will the commission investigate this scheme of forging tamsuk and seizing land with false documents, especially ones with false fingerprints?

In the commission’s terms of reference, it is mentioned that even in the case where the loan is not taken, the preparation of the document of transaction should be investigated. Uttamraj Subedi, a member of the Commission and former Additional Inspector General of Police (AIG), says that there are cases of fake tamsuks being made without giving loans. “If fake loan documents are found, the Commission is ready to consider it as a complex and organized crime”, he says. The Commission has also been given the right to recommend action against the guilty.

Sushil Kumar Yadav, a clerk at Rautahat District Court, says that 1,811 cases related to transactions were filed in this fiscal year. He says that 90 percent of these cases involved document fraud. “The plaintiff says that they lent the money, but the other side says that they prepared a fake tamsuk,” he says

Serial fraudsters

Back to Rajaram’s story. He is fighting a legal battle in Janakpur High Court against an attempt to seize his property. He had faced a similar case before. The lenders were different, but the people were the same. They made a tamsuk that said Rajaram borrowed 300,000 rupees from Lalitadevi, Trailok Chandra’s married sister. The document said that he took the loan on March 29, 2013.

Lalitadevi sued Rajaram in February 2015 for not paying back the loan. “I never borrowed any money from this family,” Rajaram says. He filed a countersuit on April 24, 2015, saying that they used his fingerprints on a fake loan. The court ordered a laboratory test of the disputed document and the report said that the fingerprint on the tamsuk was false. On January 25, 2017, Lalitadevi asked the court to drop the case after seeing the negative report. The court agreed to withdraw the case on February 14, according to Section 196 of the Civil Code (Procedure).

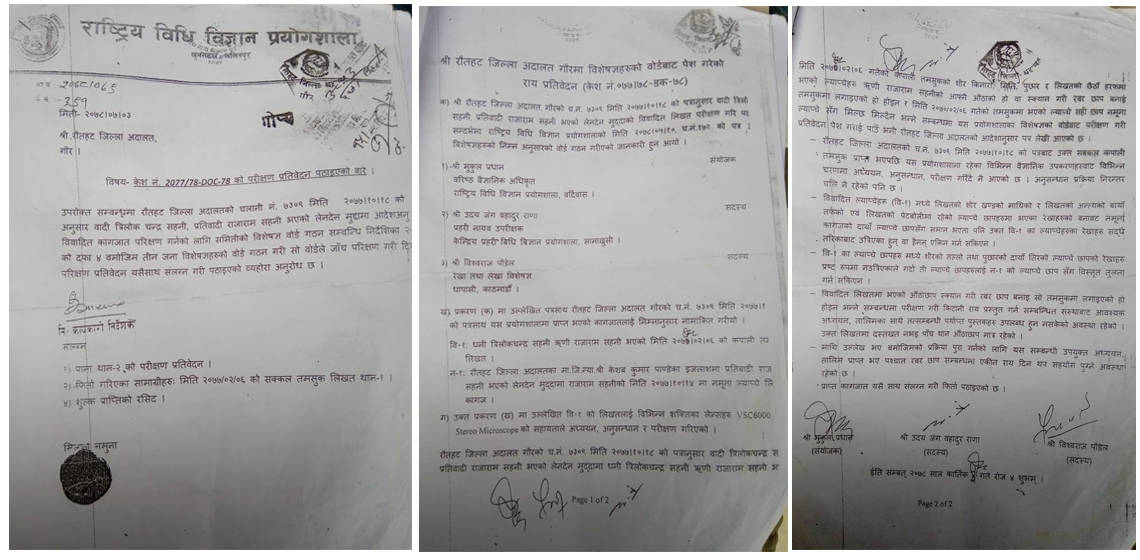

Chandeshwar Sah who wrote Tamsuk and Ramvinay Sah who filed a case by making fake fingerprints.

But the court found Lalitadevi guilty of document fraud and fined her 150,000 rupees on February 15, 2018. Ramsenhi Yadav, witness Lakshmi Sahni Malahi and Birendra Sahni, who wrote the deed, were fined 75,000 rupees each. Three months after the court’s punishment, Lalitadevi’s brother Trailok Chandra filed another transaction case against Rajaram.

The case of Baiju Sah Kanu from Rautahat shows how gangs keep harassing people without facing serious consequences. His neighbor Ramvinay Sah sued him on November 22, 2019 for not paying back 300,000 rupees dollars that he borrowed on April 25, 2017. Baiju said that the fingerprint on the tamsuk was not his and asked for a laboratory test. The court sided with Baiju after the test showed that the fingerprints were fake. Baiju also filed a fraud case during the original case. The court fined Ramvinay, Chandeshwar Sah, who wrote the deed, and Kapildev Mahato, the witness, 30,000 rupees each.

But this punishment did not satisfy the Ramvinay family. A month later, Sumina Devi, Ramvinay’s sister-in-law, filed another case against Baiju’s son Rambishwas. She said that he owed her a million rupees that he borrowed in 2015. “He would not have done this again if he had gone to jail,” Rambishwas says. The case is still ongoing.

According to Section 36 (2) of the Civil Code (Procedures), both parties need to get their transaction documents of more than 50,000 rupees certified by the local or ward committee. Before that, a tamsuk with both parties’ witnesses was legal under the existing civil law. As the code came into effect in 2018, forged documents are dated prior to 2018.

Ram Biswas says that Ramvinay’s family made another fake document with an earlier date to trap him after they lost the first case.

The government added a new clause to Section 249 ‘A’ of the Criminal Code through an ordinance last April, prohibiting unfair transactions. According to the ordinance, anyone who violates this clause could face up to seven years in prison and a fine of up to 70,000 rupees. However, since the ordinance has not been replaced by an act of Parliament, it is now on the verge of becoming legally invalid.

The ordinance, which was introduced in the House on May 7, was passed by both the House of Representatives and the National Assembly on May 10 and May 19 respectively, but the replacement bill was not approved. The government registered the replacement bill in the National Assembly on June 20, but it missed the 60-day deadline when the opposition party CPN-UML obstructed the parliament over Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal’s controversial comments at a public function. This means that until the bill is passed, there can be no legal action against those involved in unfair transactions.

Organised gangs

Arvind Jha.

Meanwhile, loan sharks have also lobbied to scrap this clause of the bill. In the second week of June, they staged a demonstration at Maitighar, demanding the removal of this clause.

In Madhesh province, loan shark illegal businesses appear to be operating in a systematic way. It has been revealed that such a group has obtained fingerprint documents and made rubber fingerprints from them, lending money, issuing tamsuk and obtaining tailored reports from forensic science laboratories.

Ramsenhi Yadav, Anil Jha, Chandeshwar Sahni are involved in preparing the tamsuk. Yadav issued a tamsuk of 300,000 rupees to Rajaram and 3 million rupees to Malbhogia. In the case of Rajaram, the court found Yadav guilty and fined him 25,000 rupees. But he assisted Yadav to issue another tamsuk in Malbhogiya’s name. On June 12, after getting a negative report from the Forensic Science Laboratory, the lender withdrew the case, saying that he could not prove the fault, so no one had to face legal action.

It has been discovered that one faction of the group is engaged in producing tailored reports at the National Forensic Science Laboratory. The laboratory’s register book confirms that a person named Arvind Jha visited the laboratory several times during the analysis of the fingerprints on the disputed document in Rajaram’s case.

The audio of the conversation between the tamsuk writer Ramsenhi Yadav and one of the victims not only exposes that this group has expanded in an organized way, but also confirms that its reach has extended to the court. In the audio, Ramsenhi claims that they ‘fix’ people in the court and forensic science laboratory in the scheme of stealing other people’s property by making fake Tamsuk. “All our people are in the laboratory and the court. Nothing will happen there,” Ramsenhi can be heard in the audio, “Our Pandit ji will call as soon as he calls, and then the work will be done. The judges are all involved. Making money filing false transaction cases.

Jha refers to Arvind Jhaas Panditji. Arvind, from Rautahat Pipra Matsari, is not mentioned anywhere in the loan transaction documents. But the victims say that he becomes active after the case goes to court. In the said audio, he says one Anil sends rubber fingerprints to Patna. “Money makes everything work,” his voice is heard, “Arvind chews gutka (a type of tobacco) worth 100,000 rupees a month.” When the arrangement does not work, this group withdraws the case from the court and avoids legal action.

For example: Birendra Sahni of Garuda Municipality-2 issued a tamsuk saying he lent 5.3 million rupees to Bedami Sahni of the same Municipality-9 dated January 2017. A year later, Birendra filed a case in court for not getting the loan back. In March of the same year, the court ordered to examine the disputed documents after the borrower claimed that he had not received the loan. After getting a report from the Forensic Science Laboratory that the fingerprints on the tamsuk and Bedami’s fingerprints did not match, Birendra filed a request to withdraw the case. Then on October 31, 2018, the court ordered the case to be withdrawn. But none of the group members who made fake documents had to face legal action.

Learning from neighbour

In 2016, a farmer in Ahmedabad, India, reported to the police that his land, which he had never sold, had been sold. During the investigation by the Directorate of Forensic Science (DFS), it was revealed that the fingerprint on the document had been faked. The Times of India reported that the technique used in the document was to scan the fingerprints taken from somewhere else by a high-quality machine and make rubber fingerprints of the same size. The news also mentions that DFS has to examine more than 100 land ownership disputes every year.

Since 2010, the Unique Identification Authority of India has launched one of the world’s largest biometric systems to provide a National Identity Card (Aadhaar Card) with a unique identity to every Indian citizen. This is an ambitious plan to digitally transform government subsidies and public welfare programs through this biometric Aadhaar card. But it was found that money was stolen from the bank account by the criminal group by forging the biometric fingerprint as well. In May 2022, the cyber unit of the Bhopal Police arrested four people who accessed the Aadhaar ‘Enabled Payment’ system through fake fingerprints and withdrew money from citizens’ accounts. This group withdrew 500,000 rupees from the accounts of 23 people and fake rubber fingerprints of 98 people were seized from them.

“In India, there is an old practice of fraud by making fake rubber fingerprints,” says SSP Siddhivikram Shah. He said that when he was the chief of Rautahat, he received complaints that people were victimized in this way in Nepal as well, so he understood that this problem has been prevalent in India for a long time.

Until recently, it was believed that it was not possible to fake a fingerprint even if a signature could be forged. But the offenders are making this impossible thing normal and making it a nightmare for many. Even our justice system and criminal investigation are not able to stop this scheme that has made many people homeless by making fake fingerprints. “This group has ruined how many people,” says Rambishwas Sahni, who is still fighting the case in the court, “Since people with influence are involved, nimukha (a term for poor or powerless people) can’t say anything. We are only able to speak this much with great courage.”