On one hand, there have been allegations that the constitutional provision regarding citizenship is discriminatory; on the other, acts according to the statute are yet to be formulated, while the Supreme Court’s verdict is not carried through. This has rendered a large number of Nepalis stateless.

Pratima Silwal | CIJ, Nepal

Jitendra Kumar Kushwaha was born in 2055BS in Dhanusha’s Mithila Municipality-7 (the erstwhile Dhalkewar VDC-2). His grandparents, who were born and lived in the same locale, never needed a citizenship certificate. But Jitendra’s father, Gurusharan Mahato, applied for citizenship at District Administration Office. The DAO turned down his application, reasoning that his parents didn’t have the citizenship certificates. With no citizenship, Gurusharan, a social worker who ran a cooperative at the village after his SLC, was limited to farming, just like his ancestors.

itendra Kumar Kushwaha

But when the then reinstated parliament endorsed Citizenship Act-2063 (BS), it opened up a way for Gurusharan to acquire citizenship. According to the provisions of the Act, endorsed on Mangsir 10, he received his citizenship based on birth from a distribution team visiting his village. According to a political consensus forged on Kartik 22 that same year, the parliament had formulated the act “considering that Nepali citizens have had troubles without a citizenship certificate”.

Jitendra’s mother, Deepadevi Mahato, however, has a citizenship based on descent. She acquired her certificate from Dhanusha’s District Administration Office on Magh 17 2063 BS, which included her husband Gurusharan’s and father Ramashish Mahato’s names. Among the three children of Deepadevi and Gurusharan, Jitendra and his brother are without citizenship certificates, despite fulfilling age criteria, while their sister is yet to reach the age.

Jitendra, a 24-year-old Bachelor’s final year student, has been visiting government offices for four years to acquire citizenship. At first, he submitted his father’s citizenship (by birth) and his mother’s (by descent), along with his birth certificate and academic credentials, to the ward office. But the ward office refused to endorse and he then reached DAO Dhanusha, which, saying that citizenship can’t be granted to the child of a man with citizenship by birth, turned him back.

According to the constitutional provision, Jitendra has the right to a Nepali citizenship taking into account his mother’s citizenship by descent. But then Chief District Officer Pradeep Raj Kandel said his office can’t grant Jitendra a citizenship. When he was denied by the CDO himself, despite reporting that his family has been residing at the village for three generations and that his mother has a citizenship by descent, Jitendra reached the Dhanusha High Court in 2075BS.

On Asar 16, 2076, a joint bench by justices Binod Mohan Acharya and Ramesh Dhakal ordered to “immediately provide the citizenship [to Jitendra], following legal procedures, and, if it’s not possible, inform the applicant”.

Brimming with hope, Jitendra reached the DAO, but he was turned away empty-handed, once again. When he requested a written response about reasons, then CDO of Dhanusha Bandhu Prasad Banstola said the citizenship was denied based on “decision from the office of government attorney”. But he didn’t reveal on what basis such a decision was taken.

After the DAO neglected even the high court’s order, Jitendra appealed to the Supreme Court on Mangsir 2 this year. A Mangsir 29 hearing by a single bench of Justice Hari Prasad Phuyal had issued an interim order to not bar Jitendra from opening a bank account just because he doesn’t have a citizenship. On that basis, Jitendra has opened a bank account at Rastriya Banijya Bank, Bardibas branch, in Mahottari. The final verdict on his case is awaited.

Jitendra is eligible to receive his citizenship according to Nepal’s constitution, acts and codes on citizenship, the global manifesto on human rights, international treaty on economic and political rights, and many other treaties of which Nepal is a signatory. But the CDO’s order has made a mockery of the treaties and rights of many like Jitendra.

The citizenship section of District Administration Office, Chitwan.

Malina Mandal, a native of Biratnagar-16 who completed her nursing studies five years ago, is still unemployed. She is jobless not because she lacks merit or by choice. According to existing provisions, one can’t practice nursing without a certificate registered by Nursing Council, and one can’t get that certificate without citizenship.

The District Administration Office, Morang has issued a citizenship by birth for Malina’s father Hara Dev Mandal on 28 Chaitra, 2063. Malina’s mother Janakidevi, however, hails from India. Malina says that the DAO has informed her it can’t grant her citizenship because her father has a citizenship by birth.

When she couldn’t appear in a ‘license test’ conducted by Nursing Council, Malina filed a case at Morang High Court on Kartik 2, 2075. On Magh 23 that same year, the court ordered that Malina be allowed to give the test. Malina gave the test but has not yet received the certificate.

Binda Ghimire, chair of Nursing Council, a citizenship certificate is a must for nursing certificate.

Jitendra and Malina are representative cases of how many Nepalis are denied citizenship even though their parents have citizenship by birth. The number of people who have been rendered stateless within the state is large. The constitution has guaranteed that children of people with citizenship by birth can acquire citizenship by descent. But for the implementation of this provision, a federal law is yet to be formulated.

The citizenship bill tabled in the parliament has been in a limbo for a lack of consensus between political parties. Hence, children of those who have citizenship by birth haven’t been able to acquire citizenship since Asoj 3, 2072, when the constitution was promulgated.

‘We don’t identify the person without their father’: CDO

After he passed his SLC in 2069 BS, Bikas Nepali, a native of Bharatpur, Chitwan, went to the DAO for citizenship, with a referral from the ward office.

Bikas, son of Ram Kumar Nepali and Juni Maya, was born on Mangsir 16, 2054BS in Bharatpur Metropolitan-26 (erstwhile Jagatpur VDC-4), according to his birth certificate.

It was on the basis of that certificate the ward had referred to the DAO for Bikas’s citizenship. While the referral letter includes his mother’s citizenship number, it doesn’t have that of his father, who had disappeared when Bikas was still an infant. Because his father’s credentials were lacking, the ward office only included Bikas’s name, surname and address in its referral.

When Bikas went to the DAO, with his birth certificate, referral for citizenship, and a copy of his mother’s citizenship certificate, he was asked for a copy of his father’s citizenship certificate. “My father ran away when I was still in my mother’s womb, leaving no documents. So I don’t have any document that would establish he is my father. How do I bring his credentials now?” says Bikas.

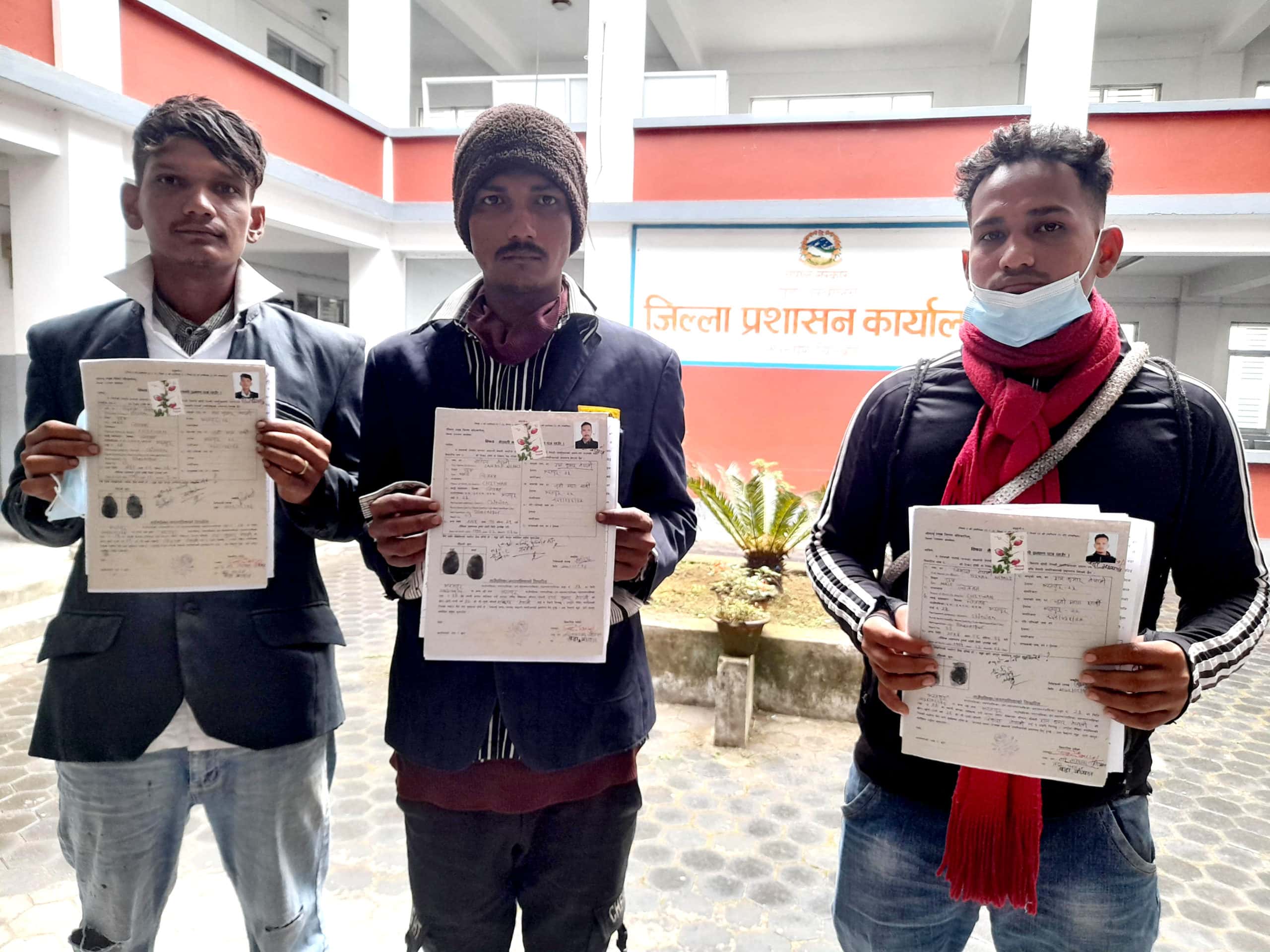

Bikas and his brothers at District Administration Office.

Bikas has since then repeatedly reached the DAO. But since he lacks his father’s credentials, the process to acquire citizenship has not moved ahead.

Bikas’s two elder brothers, Sandeep and Bishal, are facing similar problems. Uneducated, they were repeatedly turned back by the DAO officials for a lack of their father’s documents. And they gave up altogether. Because they don’t have citizenship, their life events involving marriage and birth of children haven’t been recorded either.

Bikas is Juni Maya’s youngest son. Juni Maya had thought that since she had a citizenship and her son had a degree, acquiring citizenship for Bikas would be easy. But Juni Maya is disappointed today since the DAO has repeatedly asked for Bikas’s father’s credentials.

After all attempts to acquire citizenship for Bikas fell apart, Juni Maya struggled with her mental health and spiraled down to alcoholism. She passed away two years ago. “Today, neither do I have my mother, nor a citizenship,” says Bikas.

Bikas’s three brothers on Mangsir 16 this year submitted another appeal for citizenship at the DAO, in what they called their last attempt. This time around, they have gathered the proof of their father’s death. The Chitwan District Court has declared their father dead citing he has disappeared for 24 years.

“We have gathered as much proof as we could,” says Bikas. “If we still don’t get citizenship, we will give up on calling this country ours.”

In 2043BS, Meera, a resident of the erstwhile Gaindakot Adarsha VDC-2, in Nawalparasi, got married to Noboru Mijuhasi, a Japanese national who had come to Nepal to work at the Madhya Marsyangdi Hydropower project. They gave birth to two children. In 2053, when Noboru returned to Japan, he assured Meera that he would take her to Japan, too. For four months after he returned, he was still sending her money. But after that, he was out of contact.

Meera had to raise the two sons alone. When it was time to record the kids’ birth and life events, Meera tried to contact her husband again. Noboru had assured that he would return to Nepal and register their marriage, so Meera had hopes that he might have recorded the event in Japan’s government offices. So she contacted the company Noboru worked for and also the Japanese government. Then it was revealed that Noboru hadn’t recorded their marriage or the birth of the sons anywhere.

Once Meera’s sons were old enough, they applied for naturalized citizenship. Nepal’s government acquired information about Noboru from Japan. It was revealed that he already had two wives and two daughters in Japan and had passed away on September 9, 2000 (2057BS).

Meera has mentioned Noboru’s name in all of her sons’ documents. Which is why they are eligible for naturalized citizenship rather than one by descent. But even for that, they have had to struggle for years. Documents sent through the DAO with the local unit’s referral are stuck on Ministry of Home.

“While I gave birth to them, raised them and educated them, I was alone,” says Meera. “But when they needed an identity, the authorities wanted a father. Even when they are able and educated, for a lack of citizenship, they are handicapped.”

On Poush 8 this year, Teknarayan Pandey, the Secretary at Ministry of Home, requested lawmakers to provide a recourse to Meera’s problem amid a meeting of Parliamentary Committee of Law, Justice and Human Rights.

In 2067BS, the Supreme Court had issued the verdict that “one can acquire citizenship if one among their two parents are Nepali citizens”. The verdict, equally relevant today, states, “No citizen should be denied citizenship just because officials at DOA misunderstand or misinterpret constitution and laws. It is not acceptable that one has to endure difficulties to to acquire citizenship certificate.”

Balaram KC, the justice who issued that verdict, which is known after Sabina Damai, says that after he found that many CDOs had been dilly-dallying to grant citizenship certificates citing various reasons, a circular was issued to all DOAs through Ministry of Home. “The circular was issued but the CDOs have yet to implement the verdict,” says KC.

Pandey says that following the apex court’s Mangsir 19 order, a circular has been issued once again to DOAs to grant citizenship through mother’s name.

But Chiranjivi Sharma, deputy CDO of Chitwan, argues that citizenship can’t be granted through mother’s name, unless the person presents the descent of their father. “The constitution has mandated that citizenship can be acquired via mother’s name, but there’s no law formulated yet. Which is the reason why we haven’t allowed citizenship based on mother only. But once the law comes into effect, we will do what it mandates,” Sharma says. “The court’s verdict orders to grant citizenship based on mother but not when the father’s descent is not known.”

The SC order and international commitments

In 2073BS, in a case of one one Sirjan Kharel, the Supreme Court had said that since the law has provisions to grant citizenship based on mother only, one should not be subjected to irrelevant questions about the father’s whereabouts.

In yet another similar case involving Bipana Basnet in 2075, the SC said that since both father and mother hold equal basis of descent for a child, one shouldn’t be barred from writing their mother’s surname on citizenship.

Issuing a verdict in the case of Lakshmi Kumari Sharma in 2077, the SC had ordered the District Administration Office, Kathmandu that once the person’s citizenry is established, it is injustice to subject the person through various small procedures. According to Office of Attorney General, there are over 20 precedents where the SC has ordered the government to grant citizenship based on mother.

Because constitutional provision that mandates easy access to citizenship is not carried through, thousands of people have had a hard time, says Sunil Kumar Pokharel, former general secretary of Nepal Bar Association. “It’s been six years since the constitution was promulgated, but the citizenship act is yet to be amended. Kids as young as 11-12 then are now eligible for citizenship, but they have been denied citizenship citing this or that complication,” says Pokharel, who is also the coordinator of NBA’s human rights and public relations committee. “The supreme court only issues its verdict once the case is filed, and others with similar issues continue to face trouble.”

But then the constitution itself is discriminatory when it comes to citizenship. A father can easily help his children get citizenship but for a mother, it is not exactly so easy. It is not enough to have the mother’s identity and citizenship; that of father’s is imperative, and if the father’s identity is not available, then it should be legally declared. This discriminatory provision in constitution based on gender has barred women from helping their children get citizenship.

The government meanwhile has been sidelining recommendations received from international community to amend the discriminatory provision. Its latest example is the Nepal government’s neglect of UN’s human rights council’s recommendation on citizenship during its universal periodic review (UPR) on the state of Nepal’s human rights.

Since the council’s periodic review which took place in Geneva on Magh 8 last year, Nepal has received several recommendations regarding the amendment of its citizenship provisions. During the UPR, Panama recommended that Nepal amend all discriminatory provisions against women when it comes to citizenship. Likewise, Nicaragua too suggested that Nepal ensure women’s rights and without any discrimination based on gender, provide equal rights of descent. Germany recommended that Nepal amend its citizenship act allowing one to receive citizenship based on birth and cancel all discriminatory provisions. While Finland recommended that Nepal ensure that everyone has the right to acquire citizenship through mother’s identity. Nepal has accepted all of these recommendations.

Likewise, the United Nations’ human rights committee has recommended amendment on citizenship law since it only allows one to receive citizenship based on descent if bother father and mother are Nepali, which in turn bars minorities—such as children born from unmarried mothers, from a foreign father and Nepali mother, those whose father’s identity is not proven, children of refugees and those from LGBTI community—from getting the citizenship. While Nepal has accepted all these recommendations and suggestions, it has done nothing to actually amend the discriminatory provisions.

Advocate Nabin Kumar Shrestha points out the need to amend the constitution to remove discrimination on citizenship. “Nepal had committed to implement the recommendations from UN’s member states during the UPR. It is Nepal’s responsibility to implement them. For that, Nepal’s constitution needs to be amended,” he says.

Likewise, lawmaker Krishna Bhakta Pokharel too says that an immediate solution should be forged for those increasing numbers of people struggling to acquire citizenship certificates. “It’s already been six years since the constitution was promulgated,” Pokharel, who is the chair of the parliamentary committee of human rights, notes. “It’s been a year since we received recommendations from the UN’s UPR. But still, many people are deprived of citizenship certificates despite having Nepali parents. While those without citizenship inside the country are in pain, outside, questions will be raised for us in global platforms on why we failed to implement UPR’s recommendations. What answer will we give?”