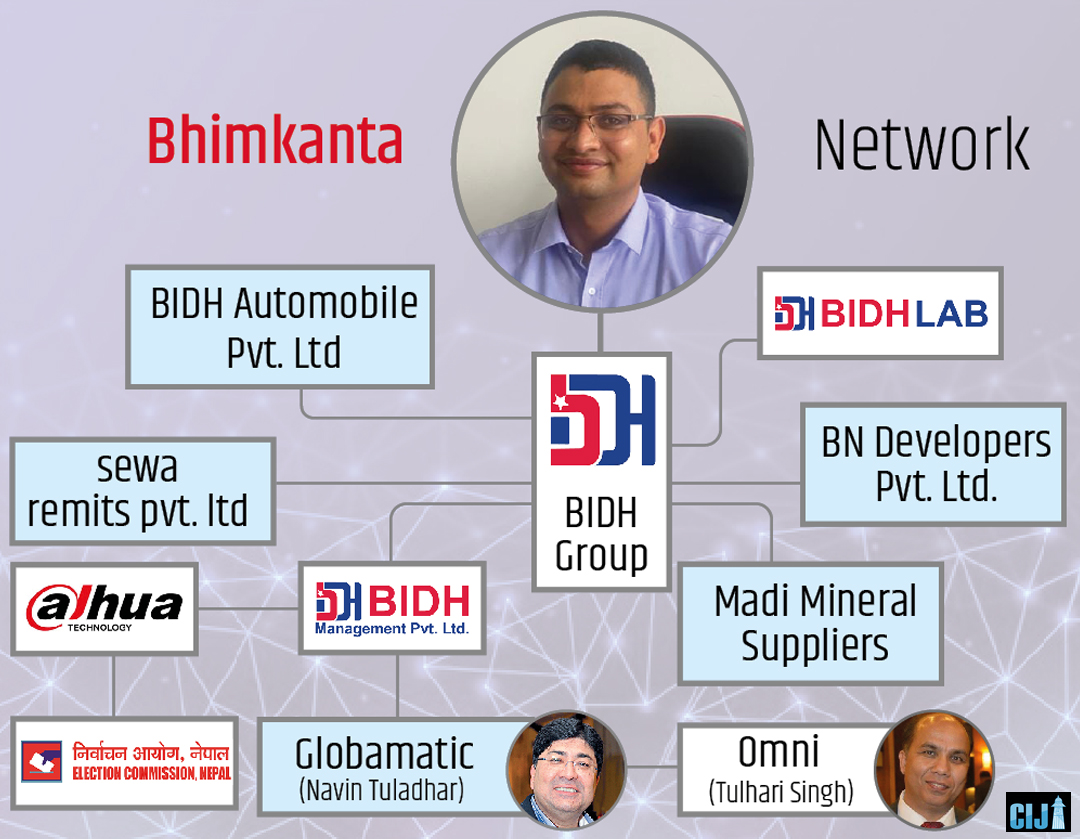

How did clerk Bhimkanta Bhandari, who started his own business by landing a government contract during the Covid-19 pandemic, become a billionaire? An investigation into his political connections and surprising business expansion seeks to find answers.

Ramu Sapkota |CIJ, Nepal

Bhimkanta Bhandari, who hails from Malika Rural Municipality, Gulmi was appointed as a staffer (clerk) at the Rural Development Training Centre, Jhapa on October 5, 2016. Bhandari, who signed the attendance register only on the first day of his work, found a way to get a transfer to Kathmandu.

The man, who worked at Local Development Minister Hitraj Pandey’s secretariat from October 28, didn’t have to return to Jhapa for four years as he roamed the corridors of power in Kathmandu. He worked at the Ministry of Federal Affairs for five months, Ministry of Finance for four months, and the Ministry of Women Development for seven months. He worked at the then Energy Minister Barshaman Pun’s secretariat for two-and-a-half years.

Bhimkant Bhandari speaking during the second municipality conference of Malika Rural Municipality, Gulmi organized by CPN (Maoist Centre).

Coincidentally, the Covid-19 pandemic struck Nepal the same time he was working for Minister Pun. On March 24, 2020, the government declared a lockdown and the next day assigned Tuhari Singh’s Omni Business International (Omni) to import medical goods including kits necessary to control the spread of the disease.

But after questions were raised about the procedure adopted to award the tender, the quality of the kits and their prices, Omni called off the deal, which was then awarded to BIDH Management Pvt Ltd. It was during this time that the pandemic put a brake on all businesses, and the common people’s economic opportunities shrank. However, Bhandari quit his government job on July 14, 2020. By the time he had quit the job, he had already bought a company, ‘BIDH Management’, and even registered a lab, ‘BIDH Lab’, under his name. He started out business by selling rapid diagnostic test kits (RDTs) thorugh BIDH Management.

According to the minutes of a meeting of BIDH Management held on April 17, 2020 Bhimkanta is the sole owner of the company, which was incorporated on June 6, 2019 to work on transport infrastructure evaluation. However, its memorandum of association was amended to make it possible for the company to import Covid-19 test kits.

Bhandari, who was already involved in a private company even when he was working for the minister’s secretariat, identifies himself as ‘BK Bhandari’; in the documents related to his private business. After the government annulled the deal with Omni to supply test kits, BIDH Management stepped in to provide the RDT to the Department of Health Services imported from China. Although the government papers suggest that the procurement deal was signed with BIDH Management, but it has been found that Omni was also in on the process to supply the goods. These two companies imported low quality kits and sold them to the government at exorbitant prices. As political leaders colluded with the company’s owner, public health issues were conveniently sidelined.

Government documents suggest that between April 23 to June 17, 2020 the department of health services procured RDTs worth Rs 228.5 million. BIDH Management, which didn’t have previous experience in supplying medical equipment, was awarded the contract even as Bhimkanta took over the company less than a year ago.

BIDH bought RDTs from Chinese company Lepu Medical Technology (Beijing). Researchers in Pakistan found out that kits made by the manufacturer have low sensitivity and don’t give accurate test results.

In Nepal, the RDTs were assessed by the Nepal Health Research Council. A meeting of experts from the council on May 25, 2020, suggested that RDTs shouldn’t be used as primary screening tests to detect coronavirus.

Even after the experts suggested not to do so, the department continued buying low-quality RDTs to help Omni’s owner Singh and BIDH’s owner Bhandari rake in profits. Dr. Prabhat Adhilari, critical care and infectious disease expert, says it was wrong for the government to promote serology based RDT. Advocate Santosh Bhandari accuses the government of compromising on Nepali peoples’ health under the pretext of emergency procurement.

When the government canceled the deal with Omni, it was already facing criticism for supplying low-grade and exorbitantly priced medical goods.

Bhimkanta’s BIDH lab in Lalitpur(left) and Bhimkanta with his car(Right).

Between March 22 and April 22, Omni had already imported RDT kits worth over 71.7 million Nepali Rupees. Omni and BIDH later distributed the kits to hospitals and clinics nationwide. This work was facilitated by the National Public Health Laboratory, a body under the Department of Health Services.

Following widespread criticism, Dr. Khem Karki, senior expert at the Ministry of Health and Population, announced on March 31, 2020 that the government wouldn’t use RDT kits imported by Omni. Officials and representatives were so much in cahoots that despite the government’s announcement to black-list the company to bar it from participating in future government activities, but bureaucrats were hesitant to take action against Omni.

The Department of Health Services wrote to the Public Procurement Monitoring Office on April 7, 2020 to blacklist Omni. But the office decided to do so only on August 25. Although the tender was canceled, the National Public Health Lab and the department distributed 75,000 RDT kits to hospitals around the country. The kits, made by the Chinese manufacturer Sensure, were bought by the ministry for a price five to ten times its marked value. Although officials tried to justify the move citing shortages in the international market, it was later found that even the US Federal Drug Administration-approved kits were being sold in the international market at much cheaper prices.

The ministry distributed the kits imported by Omni and entrusted BIDH Management to import more RDT kits even as the Nepal Health Research Council had already questioned the effectiveness of RDTs.

Officials from the ministry and the national public health lab continued to promote the businessmen at the cost of public health. Tulhari Singh, whose company Omni was working on government tender for IT equipment, entered into a partnership with BIDH Management after it was kicked out of the COVID-19 goods including RDT procurement deal.

A lab technician, who received a call from BIDH to work for them says, “Bidh invited me for an interview at Hotel Himalay, where they had set up their offices. Omni’s Tulhari interviewed me for the job,” the technician said. The technician claimed that he had seen a portable Polymerase Chain Reaction Machine imported by Omni inside one of BIDH’s refrigerators. The government had started controversial portable PCR tests for Covid-19 in Pokhara, Chitwan, Janakpur, Dhangadhi and Biratnagar using the portable PCR machines imported by Omni.

The portable PCR machines were shelved after it was found that during the peak of transmission, it didn’t produce satisfactory results. A team of experts suggested to the ministry that instead of the portable PCR, it should use Real Time PCR machines installed in different parts of the country. However, officials decided to go with portable PCR machines to further Omni’s business.

Ram Binay Sah, then deputy chief of the Provincial Lab in Janakpur, said that the portable PCR were not validated by the National Public Health Lab. The machines also didn’t function well. The lab then stopped using the machine as it didn’t give accurate results. But the number of cases continued to shoot up.

Despite this precedent, the National Public Health Lab procured another portable PCR machine made by the Chinese manufacturer USR and sent it to Janakpur. When officials there found the results to be unsatisfactory, Covid-19 testing was stalled again.

Sah says that although the Province Lab, Janakpur decided to operate a Real Time PCR machine, National Public Health Lab sent a portable machine. When testing was stopped, the people paid a big price for it as transmission peaked and some died waiting for tests.

Investigation Pending

Activists moved the Supreme Court against the government decision to procure sub-standard RDTs, and the government on March 31, 2020 banned the use of RDTs. It also recalled all RDTs sent to the provinces. Some of the kits are still lying around at the department of health services. However, BIDH was paid in full for the RDT kits. The case is still sub-judice.

Following the controversy, two officials: the then director-general of the Department of Health Services and Director of the Management Division were transferred. But no action was taken against anyone involved in the procurement.

Although then Deputy Prime Minister Ishwor Pokhrel, coordinator of the high-level COVID Control Committee, was transferred to the Prime Minister’s Office, he didn’t face any action. However, he was assigned to lead the Covid-19 Crisis Management Coordination Centre to procure vaccines. It was the committee led by Pokhrel that had decided to sign a deal with Omni for the procurement of medical equipment related to Covid-19 without issuing a tender.

After that, an investigation launched by the Parliamentary Public Accounts committee was also botched. The committee wrote to the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) on December 18, 2020 to investigate the case. However, the anti-corruption watchdog is yet to conclude its investigation,

https//hr.parliament.gov.np/uploads/attachments/nopf3bmh4h27bjm3.pdf

The story of the collusion between BIDG, Omni and the officials doesn’t end there. Bhandari, the owner of BIDH Management, established BIDH Lab Pvt Ltd. On July 28, 2020, the National Public Health Lab easily issued a temporary permit to operate the lab.

A committee formed by the National Lab to inspect BIDH’s lab found that it wasn’t competent to conduct Covid-19 tests. But even before the committee could submit its report, director Runa Jha authorized BIDH to conduct Covid-19 tests saying she has ‘orders from high level’. The lab then started conducting tests immediately.

Although the company had no experience in operating a lab, on February 17, 2021, the National Public Health Lab categorized BIDH Lab as an ‘A Grade’ facility.

Ex-minister Pun and Ale as allies

Bhandari didn’t limit his business to procure medical goods and Covid-19 testing. During the second wave of Covid-19 infections in the country, hospitals faced an oxygen supply crunch. Many patients died due to the lack of Oxygen. BIDH took this as an opportunity and started its Oxygen cylinder business. The business began from Lungri Rural Municipality in Rolpa, also a constituency of then Energy Minister Barshaman Pun. BIDH’s owner Bhandari worked with Pun when he was an Energy Minister.

Pun’s personal secretary Santosh Pun wrote on Facebook that the minister had distributed Oxygen cylinders for free. However later, BIDH Management sent an invoice of 293,000 Nepali Rupees to the rural municipality for the cylinders. (See invoice) It was found that the company sold the cylinders to the rural municipality at 26,000 Nepali Rupees per cylinder, three thousand more than the price it set for others.

(Left) Cylinder bills sold to left former minister Ale. (Right) Bill sold to Rolpa’s Lungri Rural Municipality, which is part of Barshman Pun’s electoral district.

The controversial blue-coloured oxygen cylinders were imported by Omni from China. But when Omni was kicked out, BIDH started selling them in the market. Omni had bought the cylinders at the rate of 1,200 Nepali Rupees per cylinder. BIDH sold it in the market at a price that was 20 times more than the cost price.

Although it received full waiver on import duties, BIDH sold some of the cylinders at Rs 28,000 per cylinder after receiving blessings from then ministers Pun and Prem Ale. Bhimkanta Bhandari and his team had proposed that then Forest Minister Ale distribute Oxygen cylinders with his photos on them. Ale, always looking for publicity, agreed and BIDH printed 100 stickers with Ale’s photo to be pasted on Oxygen cylinders. The company sold at least 60 of such cylinders at Rs 23,000 per cylinder to Ale, according to an invoice received by CIJ. The invoice for 60 cylinders says the minister Ale spent Rs 1.5 million for the deal. The cylinders were distributed in Ale’s constituency in Doti. Then there was a race among politicians to distribute cylinders to their voters. BIDH managed to sell 100,000 cylinders that it had stored at a warehouse in Gwarko for huge profits.

Bhandari’s wealth

Bhimkanta Bharndari’s wife Bimala, who was born to a lower-middle class family in Gulmi is a government clerk. The asset details she submitted to the government on February 5, 2022 states that Bhimkanta’s father owns three ropani of land. His grandfather owns 14 ropani of ancestral land.

The family owns around 20 ropani 12 aana land in total along with 3 Tola gold, 5 Tola silver and Rs 300,000 in cash. He also had Rs 245,000 in the bank and his wife Rs 17,000. But in the last few days, Bhimkanta’s wealth has grown leaps and bounds.

From left: Director of Omni, Tulahari Singh; director of Bidh, Bhimkant Bhandari and Barshaman Pun

According to BIDH’s website, the company has had a turnover of over USD 150 million since 2019. However, BIDH is not the only company Bhimkanta has invested in. It has been seen that Minister Pun used Bhandari’s house in Kupondole as his personal office.

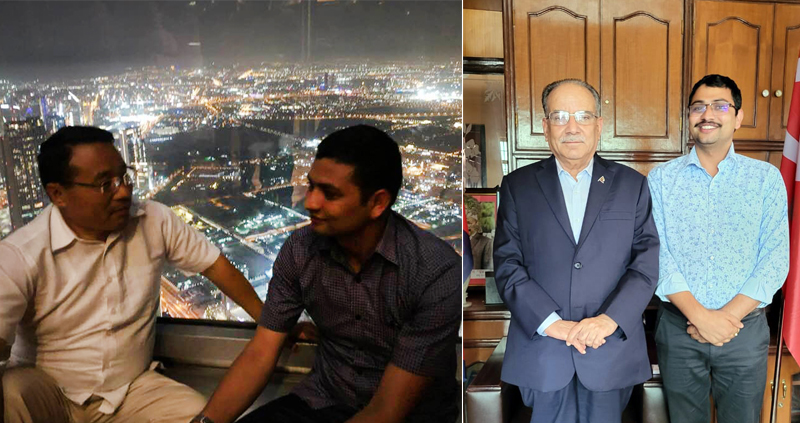

Even second generation leaders from the UML and the Maoist Centre party met at his house to discuss the merger between the two parties. Bhandari’s proximity with Pun can also be ascertained by the fact that he accompanied Pun to China and Dubai around three times. (See photo) Photos with other party leaders also show how close he is to them. (See photos)

Bhimkanta with Maoist Center Party leader Barshaman Pun(left) and party chairman Puspakamal Dahal(Right).

Invisible backup

Bhimkanta Bhandari, who was appointed a clerk at the Local Development Training Academy’s Jhapa Training Centre, stayed in government service until July 14, 2020. Minister Pun helped him land a job at Local Development Minister Hitraj Pandey’s secretariat.

Bhandari, who wasn’t affiliated with any political party during the first Constituent Assembly elections, calls himself a Maoist these days. He was even involved in the party’s recent electoral campaign.

The man from Malika-5, Gulmi now lives in Chakupat, Lalitpur-10. His wife Bimala, who was working for the General Post Office, has been suspended after the CIAA filed a corruption case against her.

Bhandari, who lived in a rented house before launching BIDH Lab, earned Rs 1.15 million as salary for his four-year stint with the government. The same figure for his wife is estimated at Rs 1.89 million. However, Bhandari is learnt to have invested a huge amount in his company even before leaving his job.

Bhandari, who profited from the Covid-19 crisis, has bought 6 ropani 5 aana land in Talku Chaur (Dakshinkali Municipality). According to the CIAA, the land bought on January 2, 2022 is priced at Rs 333 million. His wife Bimala owns 3 ropani 6 aana land in Ikudol, Lalitpur. Bimala claims to have bought the land on September 12, 2018 for Rs 200,000. Records show that the duo invested Rs 335 million on the land. However, according to those in the real estate business, the actual price of the pieces of land owned by the duo could be at least three times more than what the official records show.

According to the charge sheet filed by the CIAA at the Special Court, only Rs 2.4 million can be accounted for as the legal income of the family. Bhimkanta has invested much more than the amount in his companies. The source of the money he invested remains undisclosed.

Questions have even been raised about where Bhandari got the money to invest in Bidh Management. According to the CIAA, Bhandari has been unable to disclose the source of funds for the Rs 10 million investment he made in Madi Mineral Suppliers Pvt Ltd and the additional Rs 7.5 million he invested in Bidh along with the 3 ropani land he owns.

As the CIAA is looking at Bhimkanta’s assets by focusing on the amount he earned while he was in government service and the amount he invested in various companies during the period, it has only found questionable funds amounting to around Rs 300 million. But the investments Bhandari made after leaving office amounts to more than a billion rupees. That’s why the CIAA has written to the Anti-Money Laundering Unit to look into the case. However, the body tasked to look into cases of disproportionate assets in the private sector is yet to look into it. Bhandari, whom we tried to contact for a month, finally told us that all allegations against him are baseless.

He said that he took directors’ loans amounting to Rs 339 million from BIDH Management on various dates and invested the money in shares and real estate. On November 7, 2022, Bhandari told CIJ on the phone, “The CIAA told me that the loan I took was against the Company Act. But the CIAA doesn’t have the authority to look into the matters of the company,” he added. The CIAA says that the company’s audit report for the fiscal years concerned doesn’t show that the company took loans from any financial institution, distributed any kind of dividend or issued loans to its promoters.

Bank statements of BIDH Management as well as BIDH Lab also show no signs that Bhandari took a loan as he claims he did. That’s why the CIAA concluded that Bhandari accumulated illegal property abusing his authority while working for the government.

Bhandari claims that company promoters can take loans from the company to invest elsewhere. “There were times when we had transactions worth over Rs 400,000-450,000 in one day,” he said. According to the Company Act, promoters can’t take loans from their own company. Bhandari, who had refrained from commenting on the issue for a long time, gave a quick response after CIJ sent a text message seeking his take on the matter.

He said that he had nothing to do with Omni and that the CIAA can only investigate his earnings for the time he was in government service. “After leaving the government job, I can do any business I want, it is of no concern to the CIAA. Only the tax administration may look into it to see whether I am paying taxes or not.”

BIDH-Election Commission collusion

During the local government elections in 2079, the Election Commission decided to carry out the vote count under CCTV surveillance. It directed all 753 local governments to procure cameras and hard drives for the purpose. (https://mofaga.gov.np/news-notice/2636). Although the local governments were authorized to procure the equipment, the election commission prepared specifications for the cameras. The specifications were designed to meet the features available on Chinese cameras distributed by BIDH in Nepal.

It was only a matter of time before most of the local governments bought cameras from BIDH. After that, Bhandari became a popular figure for the commission, whose officials issued him a special ID card permitting him to visit any vote-count station around the country.

Bhandari had signed an agreement with a controversial Chinese company to supply the CCTV cameras. The Chinese manufacturer Dahua has appointed Bhandari’s Bidh Management as its distributor. A company ‘Dahua Technology Nepal’ has also been registered in Nepal.

According to a May 28, 2020 report prepared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), Dahua is a company black-listed by the US government for working with the Chinese government to carry out surveillance on ethnic minorities in the north-western province of Xinjiang. The company received a 1-billion-dollar contract to supply surveillance equipment to the Chinese government.

Involvement in fertilizer shortage

Bhandari, who claims to have made a profit of around Rs 300 million during the last fiscal year, signed an agreement with the government to supply 25,000 metric tons of chemical fertilizer.

The government-owned Agriculture Supplies Company on September 10, 2021, issued a tender to supply chemical fertilizer. The contract was awarded to Silk-Sinomatch-Globamatics-BIDH Management JV. The company signed an agreement with the JV on November 24, 2021 to supply 25,000 metric tons of fertilizer for USD 237 million. According to the agreement, the JV was supposed to supply the fertilizer by March 29, 2022. But the consignment never came. The case is now sub-judice at the Supreme Court.

Globamatics, a member of the JV, is the same company that worked with Omni to import equipment from China via a chartered Nepal Airlines flight. According to records from the Singapore Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority obtained by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), the company was incorporated in 1987 to work in solar and hydropower sectors. The company, registered in the name of Nepali national Nabin Tuladhar as an owner, has Tan B Hong, a Singapore national as its director.

The company’s director Narottam Shrestha was arrested in New Delhi in 2010 on the charge of smuggling high-quality Shahtoosh wool from Singapore to India. There is a ban on the production and sale of the wool obtained from the Tibetan antelope. This is the company Omni’s Tulhari and Bidh’s Bhandari used to capture the government contract to import fertilizer.

This report was prepared in collaboration with OCCRP.

1 hectare= 19.65 ropani, 16 aana = 1 ropani