Over the past 25 years, Nepal’s governments have blatantly ignored court decisions, especially on public interest petitions

Ekal Silwal: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Over the past 25 years, Nepal’s court system has passed many verdicts, but a followup study of 213 decisions ordering various government ministries and agencies for action were blatantly ignored and never implemented.

Teachers have been forced to work for their entire careers in adjunct positions due to the government’s failure to open new positions. Former adjunct teachers (from left) Binod Pariyar (Kathmandu), Mugalal Chaudhary (Saptari), Kumar Lama (Kathmandu), and Gurudutta Regmi (Baglung) step out of the Supreme Court’s Judicial Execution Directorate. Photo :Ekal Silwal

Of those, 92 were issued to the Home Ministry which took no action on the orders. This investigation used the right to information provisions to take a closer look at court documents on 33 of the cases categorised by the Judicial Execution Directorate (JED) and found many examples of the government paying no attention at all to the Supreme Court decisions.

Article 126 (2) of the Constitution states: ‘All shall abide by the orders or decisions made in the course of trial of lawsuits by the courts.’ But the documents with official exchanges between the courts and government agencies showed that the decisions were consistently and blatantly ignored.

In 2010, advocate Jang Bahadur Singh of Saptari registered a writ petition at the Supreme Court (SC) against the Office of Prime Minister (PMO) and the Home Ministry demanding that reproductive rights of prison inmates be ensured. On 1 April, 2011 the apex court ordered the authorities to arrange a separate maternity room so female inmates or wives of male inmates could give birth.

The court ordered the formation of a three-member study team headed by the head of the Prison Management Department within six months, and the PMO instructed the Home Minister to execute the order. But it took the ministry four years to even form the study team, even though the court wrote two letters to the ministry inquiring about the status without any response.

In 2017, the ministry finally passed buck to the Nepal Law Commission, and nine years later the ministry legal department said it was ‘in the process of implementing’ the SC order.

—

In another case, advocate Santosh Kumar Mahato filed a writ petition in 2005 seeking the juvenile court to deal with cases involving children naming the Ministry of Women, Children and Senior Citizen as the defendant. The Supreme Court ordered the government to establish a juvenile court in each district as provisioned in Children’s Act 2048.

Court documents show that the JED wrote six letters to the ministry in the past 13 years reminding it to take action. The ministry responded saying ‘implementation is in progress’. In one correspondence the ministry mentioned that ‘juvenile courts had been set up in all districts’. In reality, not a single juvenile court had been established till mid-May this year.

The person in the ministry who wrote that letter was Sarita Rayamajhi, and she acknowledges the mistake: “Since government is responsible for building the courts, the ministry alone cannot do it. The ministry is also a part of the government and we shouldn’t have responded that way. That was a mistake.”

Now, the ministry’s official line is that ‘the construction of the juvenile courts is underway’.

—

On 13 August 2003, the government and Nepal Chemist and Druggists Association reached an agreement to allow only trained staff to run pharmacies, and register or renew pharmacies only on the recommendation of the association. Advocate Jyoti Baniya challenged the agreement at the apex court, which ordered the government to form a committee headed by the Nepal Medical Council to study the agreement come up with a solution within six months.

It took six months to inform the government about the court order. Five years later, the Health Ministry requested the Medical Council to form a study team. The team had not been formed for three more years, and in 2011 the JED inquired about progress, but there was no response.

In 2013 the JED wrote a third letter to the Council. Nothing happened till December , 2018 when the court reminded the ministry about decision taken 15 years previously. No reply again from the ministry, council or department. There has been no study team.

Asked about the delay, Pushpa Raj Nepal, under-secretary at the Health Ministry passed the buck: “I cannot say anything about 12-year old case. Better to ask the department.”

We asked Narayan Dhakal, director-general at the Department of Health, for his response: “I have no idea at all. It’s an old case.”

—

Right activist Sunil Babu Pant filed a writ petition against the PMO and the Law Ministry 12 years ago at the Supreme Court to legalise same sex marriage. The court immediately ordered ‘a thorough study and analysis of international instruments relating to the human rights, and experience of countries where same sex marriage has been recognised, and its impact on society’.

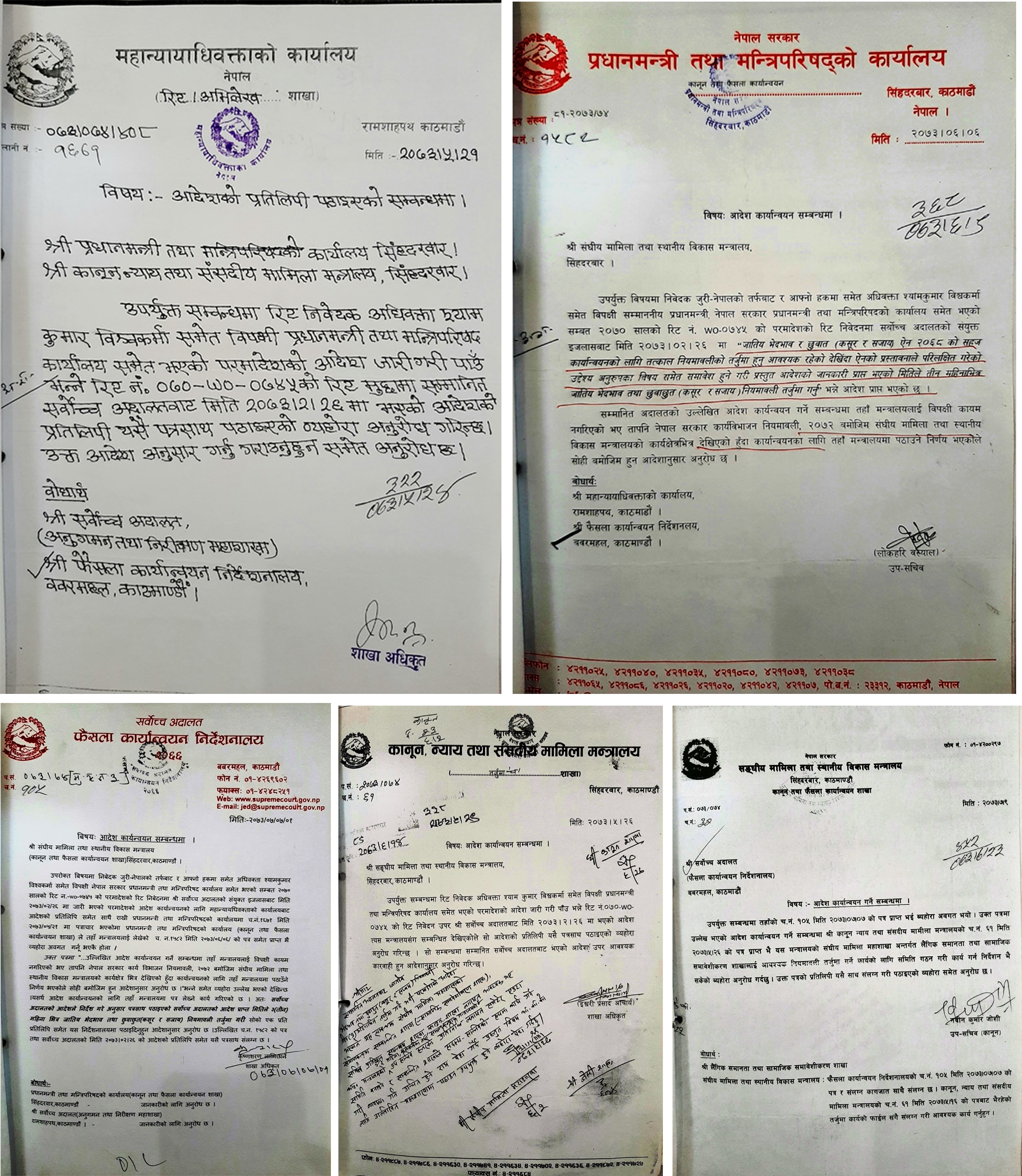

Although the Supreme Court had ordered the formulation of caste discrimination and untouchability (crime and punishment) guidelines within three months, it is yet to be implemented. Responses on the progress of the formulation process from the Office of the Solicitor General, the Ministry of Law, and the Office of the Prime Minister; follow up letter from the Supreme Court; and a response from the Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development.

It directed the government to form a committee headed by a specialist medical doctor as designated by the Health Ministry and include representative from National Human Rights Commission, Ministry of Law, Justice, Nepal Police, Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs, and a sociologist.

Neither ministry did anything for four years. Following repeated inquiries from the PMO in 2012, the Minisstry of Women Children and Social Welfare Ministry finally replied two years later saying it should not be included in the case since it was never named a defendant in the writ petition.

In 2015, the PMO wrote to the Health Ministry and Law Ministry to execute court order and submit a progress report. The Law Ministry finally informed the Supreme Court that a report prepared by the study team was submitted to the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare, but that it refused to accept the report arguing that the matter did not fall within its jurisdiction.

—

Public interest litigations have also involved matters relating to public health and the environment. A writ petition filed by nine advocates including Prakash Mani Sharma for the closure of illegal brick kilns in Kathmandu Valley is another extreme example of government dilly-dallying.

Responding a writ petition filed as far back as 2002, the Supreme Court three years later ordered the government to form a cross-ministry study team made up of various departments and agencies of the government to identify illegal brick kilns in Kathmandu valley within six months.

In the next two years, the court sent five written reminders. Fourteen years later, the brick kilns continue to pollute the Valley air, resulting in hazards to public health.

Dismayed, Ram Bahadur Thapa and Krishna Bahadur KC of Lalitpur and Ram Hari Tripathi of Chandragiri, registered two separate applications in 2019. Nothing happened.

—

The other environmental crisis is rampant sand mining and unregulated quarrying that are destroying Nepal’s rivers and mountains. Advocate Kapil Chandra Pokharel registered a writ petition at the Supreme Court in 2012 demanding that illegal sand mining be stopped along Malekhu-Naubise road section, naming the Prime Minister’s Office, concerned ministries and the Dhading District Administration Office. The court issued an immediate mandamus ordering the mining of river beds be stopped, and stipulating the maximum load of sand trucks and fining those exceeding the limit.

In 2013, the PMO instructed the then Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development, Forest and the Ministry of Soil Conservation and Environment Ministry to execute the order. It sent a reminder in 2015. The Ministry of Forests said that the implementation of the order was not possible from the Centre, and said it had passed it on to the Dhading District Forest Office. In 2018, the Supreme Court asked for an update, but has not received a reply from any government agency since.

—

There are also delays in executing orders on public transportation fares. Consumer rights activist Jyoti Baniya filed a writ in the Supreme Court in November 2006 asking the government to adjust public transport fares and insure passengers and their goods.

Nothing was done till 2011, when the court sent a reminder to the Department of Transport Management. The department replied in 2013 that it had already implemented the decision, but it had not. The court followed up in 2018, and has not heard from the department since.

—

A representative image of follow up files gathering dust at the Supreme Court’s Judgement Implementation Directorate.

Advocate Padam Bahadur Shrestha filed a writ petition in 2018 against 17 government offices including the PMO demanding that safety measures be adopted while laying pipes for the much-delayed Melamchi Drinking Water Project. In court ordered government agencies to adopt all possible safety measures including carpeting until work was completed. Delay in the execution of the court order led directly to the death of bicyclist Shyam Sundar Shrestha, 38, that year after he fell into an open manhole at night.

—

Why such apathy on the part of the government to court orders? Rajendra Kumar Poudel, spokesperson at the PMO, blames an unaccountable bureaucracy. “The transfers of civil servants is so frequent, how can you hold them accountable?”

Gajendra Bahadur Singh, director general of JED, says state mechanisms treat the Supreme Court as an institution that can be ignored with no repercussions. He adds: “This negligence is promoting impunity and an erosion of the rule of law and good governance.”