In the eight districts of Province 2, 200,000 children who ought to be in school are outside of it. Why are so many students denied education even as the constitution says ‘compulsory’ and ‘free’ education is their fundamental right?

-Kalpana Bhattarai : Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

When the government announced the temporary capitals of the seven provinces in January, two contrasting events unfolded in the two major cities of Province 2. While there was celebration in Janakpur, voices of protest reverberated through Birgunj. The city, which considered itself worthier for the title than Janakpur, was angry.

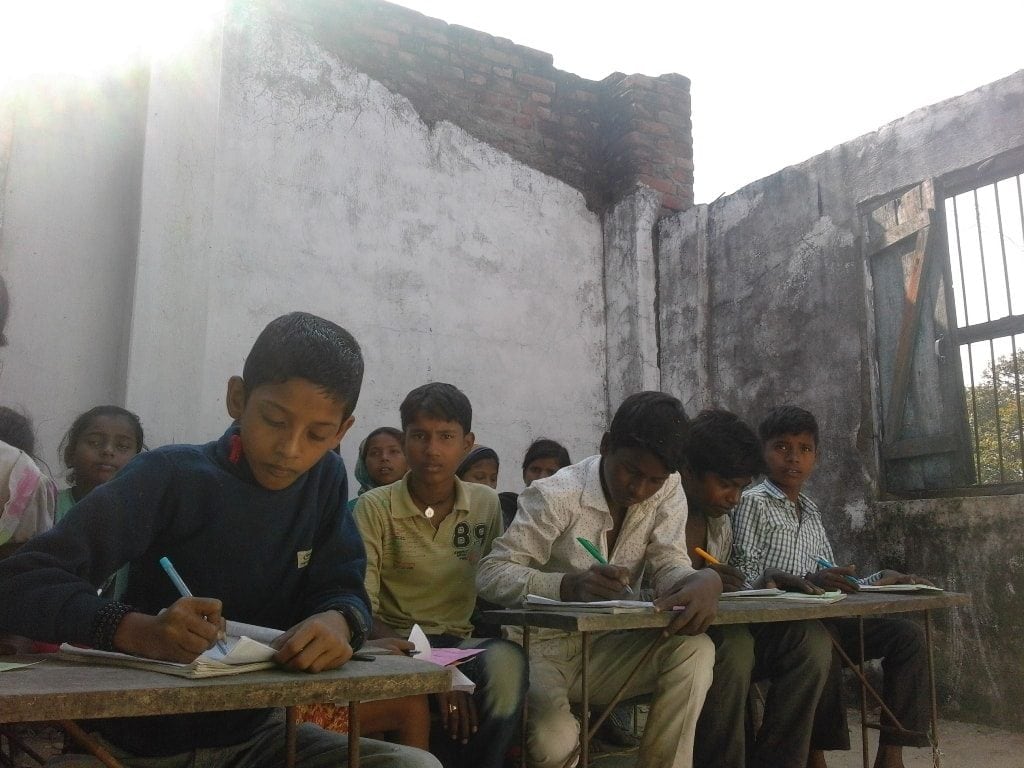

Childen sitting for exams at Hanumandatta Bishwonath Public Secondary School, Madhawa, Manarasiwa Municipality-10, Mahottari. All three buildings are unfit for students.

Both the cities have reasons to feel that they deserve the title more than the other. But one figure puts both the cities to shame. Both Janakpur of Dhanusha and Birgunj of Parsa—the two cities in contention to host the capital—have a dark record when it comes to sending children to school. These two cities are where the most children are out of school in the country.

Figures from the Ministry of Education show that Dhanusha and Parsa are the top two districts where children have been denied their right to go to school. In Dhanusha, 27,297 children do not go to school while in Parsa the figure stands at 27,105. The other districts that complete the ranking are Bara, Sarlahi, Rautahat, Siraha, Saptari and Mahottari.

According to a survey conducted by the ministry a year ago, 191,221 students in Province 2 did not attend school. Of them, 25,344 are of primary school going age and 135,877 fit to be in secondary school. Similarly, more girls are skipping school than boys.

Figures from Province 2 stand out even when they are compared with those of other provinces. According to figures from the Education Ministry, 59,904 children in Province 5 are not attending school. In Province 1, the figure stands at 49,037 and in Province 3, there are 32,988 children who do not go to school. In Province 7, the figure stands at 29,188. In provinces 4 and 6, a total of 14,616 and 13,845 students are out of school, respectively.

Although Province 2 is relatively ahead of other provinces in terms of transportation, access to communication, education, and the availability of infrastructure, there may be questions why are so many children in the state not attending school. We have tried to dig out the reasons.

Poverty closes doors

Why do the children in the Khairatol neighbourhood not attend school? Anyone who comes to this place can get an answer. A month ago, when we visited Jaleshwor Municipality-3, Khairatole, a neighborhood in the Mahottari district headquarters, we met nine-year-old Radha Sada who was doing the dishes while 11-year-old Sanjila Sada was babysitting her siblings, having finished the household chores. Sanjila is the eldest child in the family and as her parents leave home early to look for the day’s work, she has to take charge at home. Her younger sister Radha was there to help.

Ten-year-old Anu Sada, who lives in the same neighborhood, was also busy looking after her siblings, cooking, washing the dishes and cleaning the house. Fifteen-year-old Lalita Sada was working in her paddy field.

Ten-year-old Anu Sada, who lives in the same neighborhood, was also busy looking after her siblings, cooking, washing the dishes and cleaning the house. Fifteen-year-old Lalita Sada was working in her paddy field.

Most Musahar children in Khairatole spend their day doing what these children were doing. Young children do all kinds of work while those in their early teens, along with their parents, work waged jobs.

Fourteen-year-old Gokul Sada is an example. Although he wants to go to school, he hasn’t had the opportunity to step into a school. “Our father’s earning is not enough to run the house, so I also go to work,” he says. None of Gokul’s brothers and sisters has received formal education. His elder sister has already tied the knot, an elder brother works in India and a 12-year-old brother works alongside him.

Twelve-year-old Kalawati Sada has a similar story. Her parents work, she manages the house. Eleven-year-old Anil Sada studies in Grade 5; his sisters have never been to school. Describing the situation in his village, Khairatole’s Biseshwor Sada said, “Children as young as 12 start working on other people’s fields [to work].”

According to Samaj Bikas Kendra, an NGO working in the area, there are 95 children in Khairatole. Thirty of the 90 have enrolled in a school, 65 have never been to a classroom. Not a single person from among the 40 families that live in the area has ever passed Grade 10.

These 40 families live on land that is barely enough to accommodate a hut. The hut is so small that there is not enough space for everyone to sleep comfortably.

Although marriage at an early age, lack of awareness among parents that children are to be sent to school, and the parents’ ‘more-hands-less-burden’ thinking are common problems here. At the root of all problems is poverty.

Samaj Bikas Kendra’s ‘field officer’ Rupesh Pashwan said that his organisation was running a nine-month course for girls who are out of school. The goal is to send them to school after the course. Twenty-one girls attended the course, but none of them goes to school. This maybe the reason 50 per cent of women in the village do not have citizenship. Most children do not have birth certificates.

The wall of traditions

However, the story of children in Mahottari’s Samashi Rural Municipality-6 (Islamabad) is a bit different. Eighteen-year-old Ayesha Khatun had to drop out of her madrassa (Islamic school) after learning enough to read the Koran (the holy text of Muslims) to help her mother at home.

Girls studying at Madarsama, Ramoul, Siraha municipality-4.

It’s been three years since 12-year-old Nagma Khatun also quit school to help her mother. Another 12-year-old Samma Khatun left her madrassa after learning Hindi and Urdu and the Koran. The reason: the produce from their six kattha (0.5 acre) land was not enough to make the family’s ends meet. Her father had to go around looking for work and she had to take responsibility of household chores. Seventeen-year-old Sajiya Khatun and 18-year-old Jaistha Khatun, both of whom live in the same village, have never been inside a madrassa.

This is a neighborhood where none of the children goes to school. The parents only emphasize the religious education provided by the madrassas. However, of the 500 children who live in the neighborhood, not all have completed their madrassa education. The handful of children who finish their madrassa education head to India in search of work, others do not wait to do so; they leave without completing their education. Most children are busy doing their household chores.

Around two kilometers from the village lies a secondary school. But even for those who have completed their madrassa education, the school is out of bounds. Asgari Khatun, a mother, said, “If we send them (our girls) to school, who will do the household work?”

Another mother Rubeda Khatun said, “After the daughters finish their madrassa education, we need to teach them household work, and marry them off.”

Shekh Bakaulla, a father, said religious education has become compulsory in the community and for that reason they have the tradition of sending children to school. The sons need to go out and find work. The daughters need to walk long distances to go to school and this is not safe. These are the reasons the villagers do not send their children to school, he said.

According to Nehaz Ahmed, a field officer at Samaj Bikas Kendra, members of the Muslim community in the area are poor. He said, “They believe that if they let their daughters out of their house, they will be up to no good.” Maulana Sheikh Salauddin Rauf, a teacher at the Haijan Azazia Siddiqiya Madrassa, said religious education was enough for children. He said, “There is no need to study more than what is taught in the madrassa.”

Madrassas normally offer education up to the fifth grade. What is taught there is quite interesting. Maulana Rauf said, “We teach girls how to be disciplined and how to keep the family and the husband happy. We also teach them not to go out without a burka (veil) and to not talk to strangers (men).”

Of the seven wards in the rural municipality, wards 2, 3 and 6 have majority Muslim populations. The village has three community schools, six private schools and six madrassas. The Islamabad neighborhood is located around 2 km from East Champarman District’s Kanwa bazaar in the Indian state of Bihar. Similarly, 20 km is the distance between the neighborhood and the district headquarters of Jaleshwor. Most residents of the village are poor. They rely on agriculture and waged labour in India to eke out a living.

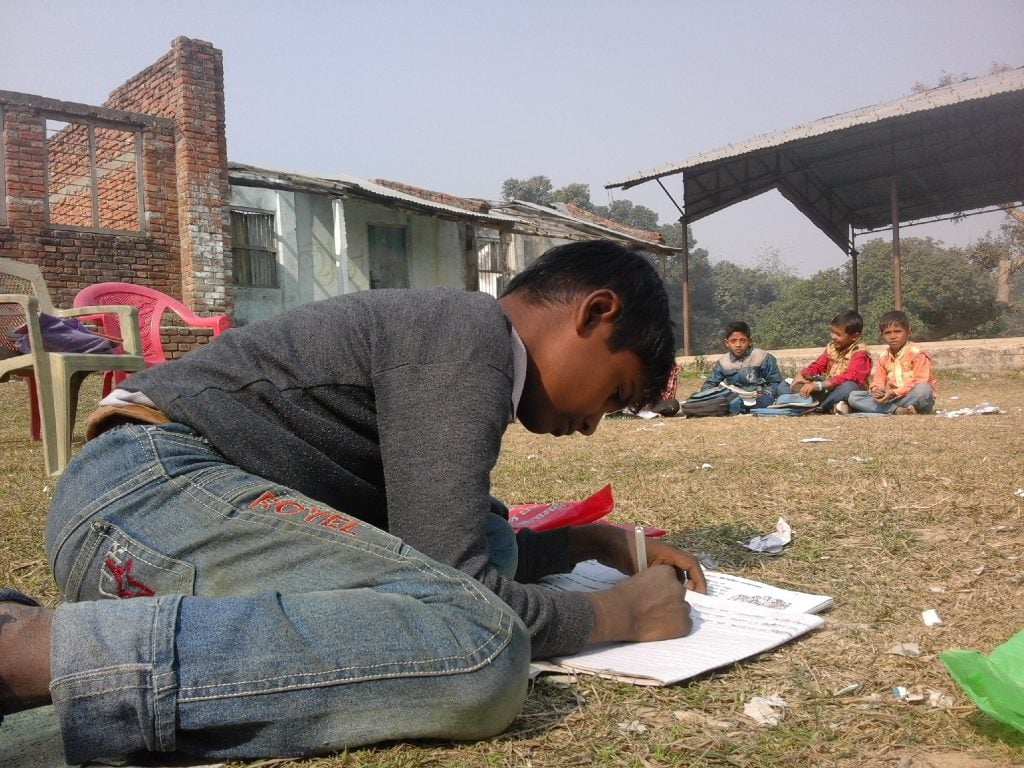

Childrens of Musahar area, Rajpur, Amargariya, Bishnupura-3, Siraha who don’t go to school.

The Ramaul Dakshin (South) neighborhood (Kutipokhari) in Siraha district’s Siraha Municipality-4 is home to 20 families. The families do not have any land of their own. They have built their huts on barren land. Around 50 meters from the settlement lie two madrassas and a school. But only 20 of the 80 Muslim children in the neighborhood go to the madrassa—their attendance record is poor. There is not even a single child who goes to school. Children in their early teens go out with their parents to look for work. Eighteen-year-old Abdul Karim said, “I earn Rs 600 after a day’s work. This is just enough to feed the family. How do I send my siblings to school?”

In Ramaul Uttar (North), a girls’ madrassa has been in operation for the last three years. The boarding school teaches 139 girl students Islamic tradition and English, Hindi and Arabic languages. Some of the students come from outside the district; some are even from India.

All teachers in the madrassa are women. The girls are not allowed to venture out of the school. In exceptional cases, they can go out under one condition: they need to put on their burka (veil). According to the madrassa’s principal Mustafir Hamani, the girls are taught to communicate in Urdu and Arabic. They are also taught the Koran and ways to keep their husband happy. They are also taught not to talk to men they don’t know. Hamnai also says, “This is all that they (the girls) need to learn. Going beyond that is unnecessary.”

Most parents do not send their children to school after they complete the madrassa classes. Local social worker Mohamed Sahid said, “It is necessary to send the children to school after they are done with the madrassa. But the parents here don’t understand this.”

One hundred children from 200 families living in Ramaul Uttar are not admitted to school. They have not even joined madrassas, says social worker Sahid. The neighborhood also has two madrassas and a school. Poverty, along with a disinterest among parents, was the driving factor, Sahid said.

Those who attend the school or the madrassa have a poor attendance record and they drop out at an early age. There are some who forge papers to lie about their age and obtain passports to travel abroad for work.

The other reason children do not go to school is domestic violence. Forty-five-year-old Shahnaz Khatin of Ramaul Uttar was abandoned by her husband, who married another woman in India. She has three children. Shahnaz has no option but to work to make her ends meet; she can’t send her children to school. There are 20 others in the neighborhood who are victims of their husband’s mistreatment. While some of them have been abandoned by their husbands, others were kicked out of their homes. Around 40 children in the neighborhood come from broken families.

Lohana village in Janakpur, the temporary headquarters of Province 2, is home to Khan Kahe Barqat, Nepal’s biggest madrassa. Here children of both sexes are taught in separate classrooms. The 70 girls in the school are not allowed to leave the building where their classroom is located. Male teachers who teach boys are not allowed to enter the girls’ section. Most parents who send their children to this madrassa, known for its stringent discipline, do not want to send students to schools after they are done with the classes there.

No money, no classroom

When this reporter visited Hanuman Bishwanath Janata Government Secondary School at Manarasishawa Municipality-10 on November 30, 2017, not a single student was around. A school teacher and Babita Pandeya, a teacher from the Child Development Centre, were there. The school was closed to mourn the death of a student at another school, according to Pandeya.

In fact, it was the month of Mangsir (mid-November-mid-December), the rice harvesting season, which forces students out of school and to the farm fields. One of the students, Gudiya Khatun, a fifth grader, was carrying a bundle of paddy. “Our school was closed because it’s a harvesting season,” she says.

In fact, it was the month of Mangsir (mid-November-mid-December), the rice harvesting season, which forces students out of school and to the farm fields. One of the students, Gudiya Khatun, a fifth grader, was carrying a bundle of paddy. “Our school was closed because it’s a harvesting season,” she says.

The school was established in 1963, but the building’s roof and walls have been damaged. As a result, students are taught out in the open. None of the eight rooms in the four buildings is in good condition. “The rooms are in serious disrepair. So we teach them in the open field,” says Ram Rao Raut, a teacher.

The primary school has a principal and three teachers including one provided by the Child Development Centre. Students of the centre and grade are taught in one classroom. Grade two and three students are also crammed into one classroom. Students of grades 4 and 5 share one classroom. Lack of blackboard meant lessons on mathematics were ineffective, according to Raut.

Lokendra Sada, a parent, says he was reluctant to send his children to school because of the poor state of infrastructure. The students come from marginalized communities including Dalit, Muslim, Kurmi, Chamar, Lohar and Sada, but the school suffers from utter neglect, says Dilkas Ansari, a local. “The district education office seems uninterested in upgrading the school’s infrastructure,” says Raut. Only 40 per cent of the school’s 261 students attend classes on a regular basis.

Many students of the school, one of Nepal’s oldest, however, have become professors, doctors and engineers. But only one student from Musahar Tole, where the school is located, has passed SLC. Yogendra Sada, 36, the lone person to have completed school education from the local Musahar community, registered at Bhaugulo Bhaiyadai Gulabdai Janata Secondary School in 1999 for SLC.

Yogendra has three sons and a daughter. But he could support education of a daughter and a son only up to the primary level. “I couldn’t study beyond SLC because I didn’t have money. Now my children are in the same predicament,” he says. Among the 60 children from the Musahar community, 20 have never been to a school. Those who have been enrolled in school don’t attend it regularly.

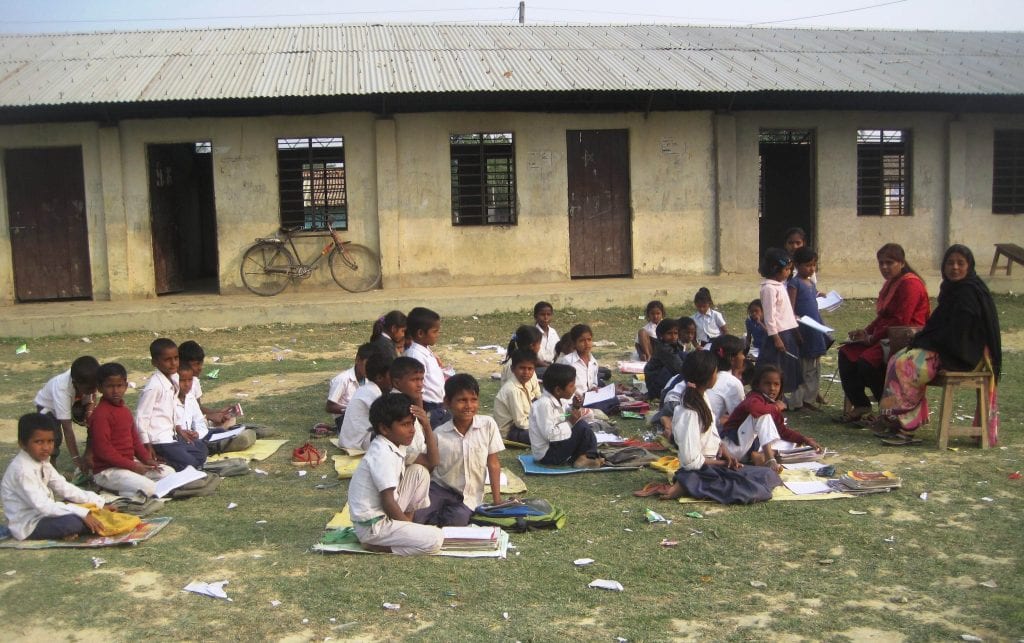

Due to shortage of classroom, students sitting on ground giving exams.

Radhika Sada, an 8-year-old girl at Bishnupura Rural Municipality-3, Rajpur, Musahar Tole, attends classes three days a week. She is engaged in household chores the rest of the week. Rakesh Sada, a 10-year-old fourth grader, misses his class because he has to look after his younger sister.

Fourteen-year-old Anita Sada, who lives in the same neighborhood, dropped out of school after Grade 2. Having dropped out due to household work she is tasked with, she now works on other people’s fields. Raju Sada, 13, dropped out of school after Grade 3 two years ago; his younger brother doesn’t go to school.

Eleven-year-old Gambhir Sada, a fifth grader, dropped out of school after he could not handle the twin tasks of looking after his sibling and helping his parents with household duties. The neighborhood has about 90 households and an equal number of children of school-going age. Among them, 30 children have never stepped into a school. Those who have been enrolled in the school don’t attend classes on regularly. When asked about lack of enrollment and irregular attendance, almost everyone replied that they have to look after their house because their parents are usually away from home to earn daily wages.

Jyoti Mallik, a 17-year-old from Siraha Municipality-2, Goriyani, dropped out of school while studying at Grade 6. Now, he is a daily wage worker in India. His younger brother studies in Grade 6, but his younger sister, despite being enrolled in school, doesn’t attend classes. Suresh Mallik, who dropped out after studying up to the eighth grade, works at a hotel in India.

Twenty-five families of the Dom community live in the neighborhood, which has 25 children of school-going age. But none of them goes to school. Only three children from seven families of Mallik Tole in Bariyapatti Rural Municipality-3 of Siraha district go to school. But they don’t attend classes regularly.

The Dom community suffers from discrimination. The so-called upper caste people don’t allow them to work except cleaning. “The upper caste people don’t employ us. We eke out a living by making Nanglo (bamboo tray used to winnow food grains) and Bhakari (woven bamboo container),” says Sita Mallik.

Kuwa village is 100 metres away from Shree Secondary School at the Janakpur Sub-metropolitan City, Ward no 12. Sumitra Pandit is a fifth grader at the school. But she was at home instead of school. “Classes are not run well. That’s why I didn’t go to school,” she says. Birendra Nayak, a local, says, “Teachers don’t arrive on time. Even if they are punctual, they don’t prepare well for their lessons. That’s why students don’t want to come.”

Childrens of Masuhar community of Khaira tole, Jaleshwor, Mahottari who don’t go to school.

Though Ram Awatar Yadav, the school principal, declined that classes were irregular, he admitted that many students missed their classes. Only half of the primary level students attend classes and most don’t come during seasonal work. The dropout rate at the school, which has 800 students, is 20 per cent, according to him. Girl students are more likely to drop out than boys. “Most are married off when they enter the 9th or 10th grade,” he says. “Most girl students drop out due to child marriage and most boy students drop out to travel abroad for employment.”

Around 700 students are enrolled to grades 1 to 8 in Murarika Higher Secondary School in Jaleshwar, the headquarters of Mahottari. Around 400 study at secondary level. This year, 100 students seeking admission were turned away, according to its principal, Sanjib Jha. Here too, 15 per cent primary students don’t attend classes on a regular basis. The dropout rate is 10 percent, according to Jha.

Around 18,045 children of school-going age haven’t been enrolled in Mahottari district, according to the Education Ministry. Around 50 NGOs are working to have them enrolled at schools, according to the ministry. The campaign has helped 2,000 children enroll at schools, but they also don’t attend classes regularly.

“We are trying to enroll those who are out of school,” says Thulo Babu Dahal, the district education officer. “Our goal is to enroll 5,000 children in the next academic year.” Rojeshwar Jha, a section officer at the district education office, says livelihood was the main cause for the high dropout rate. “It takes time to study and then earn a living. But if you join the labor market, you start earning [soon],” he says. “That’s why parents want to send their children to the labour market rather than to school.” The district is home to 312 community schools, 92 private schools, 546 child development centres and 90 madrassas.

One million children of school-going age are out of school in Nepal, according to a recent report of the Education Ministry. The number of students who drop out of schools is also very high, according to the report, released in 2016. Around 4 percent Nepali children are out of school, according to the report ‘All Children in School’, jointly prepared by UNICEF and the Nepal government. The figure of out-of-school children is around 1 million.

Why are so many children out of school? “First, parents lack awareness about education. Second, they need money. Third, the schools don’t present good environment for learning. Social context also plays some role,” says Ananda Paudel, an undersecretary at the ministry’s monitoring and evaluation section.

A 70 million-rupee project

Some 27,297 children are out of school in Dhanusha, where UNICEF and NGOs have spent 18 million rupees in the last three years to enroll and retain them at schools. The district education office spends an additional 500,000 rupees on the campaign.

Children of marginalized communities such as Dom and Musahar start as daily wage workers in their early teens, which makes enrolling them at school difficult, according to Danikanta Jha, deputy district education officer. Retaining them at school and ensuring regular attendance is challenging, he says.

Around 70 per cent students attend classes at the primary level, but attendance in lower secondary and secondary level is 50 per cent and 20 per cent respectively, according to Jha. Parents here feel that their children won’t get a job despite their education. So they inflate their age to apply for passport in order to travel abroad to work as migrant workers.

In Siraha, 22,895 children are out of school. The district education office has allocated 6.6 million rupees to a campaign for students’ enrollment and retention. Around 10,601 children have been enrolled as part of the campaign, according to a record at the district education office. But many of those don’t regularly go to school.

Similar campaigns have been launched in 28 districts targeting out-of-school children. The Department of Education is the apex body to drive the campaign, with district education offices handing out funds to Community Learning Centres for its implementation. But some DEOs have handed out funds to NGOs against the procedure.

The campaign is going on in all the eight districts of Province 2. In the current academic year, a total of 71.82 million rupees has been earmarked to run the campaign in 15 districts.

(Reporting contributed by Surendra Kamati in Siraha)