Sixteen women have died in Taplejung in the past three years from excessive bleeding while delivering babies at home. Health volunteers, local people’s representatives and state agencies shrug off their responsibility saying ‘we had no information’.

Sitaram Guragain: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Pembalyamu Sherpa from Maiwakhola rural municipality – 5

» Pembalhamu Sherpa was sitting on the platform outside her house when this reporter reached Kamsang village in Maiwakhola Rural Municipality-5 on November 20 to find out about women who had died from complications during delivery. Millet had been spread to dry in the sun on the courtyard near a chicken’s coop. Two goats were tethered on the field close by. Asked if she was still able to tend to the animals and birds, Pemba asked back: “Who will if I can’t? Death took away my daughter-in-law and granddaughter.”

The 91-year-old broke down several times as she narrated how her dear ones had been snatched away from her. “I had been destined to bid a final farewell to my daughter-in-law and granddaughter from this courtyard,” Pemba lamented, wiping her tears with one hand.

Lhakpa Ongmu Sherpa died half an hour after giving birth to her youngest daughter on the morning of December 30, 1998. “Bleeding didn’t stop after childbirth. The placenta did not come out either. There was a pool of blood on her bed. I mustered the courage to take the infant in my lap. My daughter-in-law was laid to rest. I fed the orphaned granddaughter from my breasts,” says Pemba. She could not send the baby to school as it was far away. “Two years later, his father died too.”

Pemba’s tragedy did not end here. Now an adolescent, the granddaughter came back home last year. She was pregnant. She never woke up after going to bed on the night of December 9, 2018. “She had delivered a baby that night. I found both the mother and newborn dead in the morning,” said the nonagenarian, taking a deep breath. “I lost both my daughter-in-law and granddaughter in this house.”

Pemba Jangmu had the same fate as her mother 21 years ago. Politics changed and time changed but this sorrow of Mauwakhola of having to die during childbirth remains.

Pemba’s neighbour Sangbu Sherpa said on November 20 this year, “This cat is her only companion. I came to know about the death from delivery complications only the next morning. This is our condition.”

Kamsang village has no health post. The nearest health facility is two hours’ walk away. Pemba Jangmu was married with Mingma Ringjen Sherpa of Athrai Triveni Rural Municipality-5 two years ago. Due to the poor economic condition of her husband, Pemba Jangmu had been staying with her grandmother since she got pregnant. The 20-year-old did not see a doctor even once during her pregnancy.

According to the working guidelines (2075) on air transport of critical pregnant women prepared by the Ministry of Women, Children and Senior Citizens, committees have been formed at the centre, and the local federal unit led by the respective governing chief to rescue needy women and to provide quality care for them.

But local recommendation committees are found to be uninformed that they need to recommend the rescue of pregnant women in critical conditions. Rural Municipality Chairman Rajan Thatlung said that he had no information about the death of Pemba Jangmu. “Long since the incident, nobody told me about it. I only learnt about it from you.”

» Kabita Limbu, 32, of Phungling Municipality-10 Phurumbu in the Taplejung district headquarters delivered a baby at home on February 5, 2019. Since the placenta got stuck for two hours, she died from excessive bleeding at 5 am. According to Deuman Gurung, assistant health worker at the Phurumbu Health Post, she had been in labour since the day before. “Family members are said to have ruled out the need for taking her to hospital. We were not informed about her labour pain lasting more than 24 hours.”

Kabita’s first child is 12 years old. The health post is half-an-hour’s walk away and the district hospital is one hour’s drive away.

Kabita had visited the health post only in the fourth month of pregnancy. As she did not get her condition examined in the sixth, eighth and ninth months, and she was not given iron and maternity safety pills. Kabita had given birth to her first child at home too. According to female community health volunteer Gangamaya Limbu, she had refused to go to hospital for delivery. “When I counseled her two days before her death, she said she would rather die that deliver at hospital,” said Gangamaya.

Ward Chairman Gam Bahadur Limbu blames the family’s negligence for the death. According to Kabita’s husband Makar, her labour had started earlier than expected. “I made preparations for taking her to hospital but she refused. That was her fate,” he said in a tone of resignation.

Ward chairman Limbu says there is a lack of health awareness in the village. “We have many more tasks and can’t pay attention to this only. Villagers don’t understand,” said Limbu, clarifying that the people, most of whom are poor, have misconceptions that hospitals charge a lot of money.

» Anisha Shrepa, 16, of Nalbu in Meringden Rural Municipality-6 got into labour on December 5, 2018. She reeled under pain at home for two days but the baby was not delivered. In the evening of the third day, health workers from the health post two hours’ walk away arrived and suggested taking her to the district hospital. “Her condition had got too serious when I examined her at night,” said Pinky Yadav, chief at the health post. “The relatives were adamant that her condition was common. Her father-in-law argued that the baby would be delivered in the third day of labour.”

According to Yadav, Anisha’s relatives were not ready to take her to hospital even if she had arranged for a stretcher and an ambulance. The baby was delivered at 2 am but the placenta did not come out for two hours and the new mother died from excessive bleeding. “We were helpless as the relatives were defiant,” said Assistant Health Worker Nabin Tamang, who stood by the whole night. Rural municipality deputy chairperson Kalpana Tumbahangphe expressed ignorance about the case. “I’ll inquire about it,” she said.

» Dilusha Khimding of Nangkholyang in Pathibhara Yangwarak Rural Municipality-1 was not happy that she got pregnant at an advanced age. The 38-year-old was ashamed to come out in the public. Pregnant 10 years after her last child delivery, Dilusha did not visit a health facility for medical examination even once during the pregnancy.

At 9pm on October 30, 2018, she gave birth to a girl as her fourth child. She bled profusely since the placenta was retained for two hours and died. “The baby was born healthy not after a long labour,” said Mankumar Khimding, her husband. “She became sick immediately. We could not think of taking her to hospital.”

After her condition got severe, Mankumar had brought in a health worker who lived nearby. “She happened to lose consciousness after delivery. They put her in a doko [bamboo basket] and shook her vigorously with an aim to take the placenta out,” the health worker said. “When I got there, four people were shaking her in a doko. I asked them to take her out and stretch her on a bed. She had already died.”

Even after Dilusha’s death, a witch doctor had been called to do his wonders to bring her back. Other family members also did not want to bring out the news of her late pregnancy. Female Community Health Volunteer Mangena Khimding said Dilusha had delivered the baby 12 days after the due date. “A week before her death, I visited her at her house and advised her to go to hospital,” said Mangena. “I delivered three children at home, and will give birth [to this one at home] too now,” she was told.

Auxiliary nurse midwife Sushila Bhattarai of Nangkholyang Health Post said many women don’t visit them due to shyness. Ward Chairman Jiban Raj Khimding says there is no remedy for those who are ashamed to visit a health organization. “What shall we say at this age?” Khimding asks. “Why be shy when the law permits for bearing children as the couple wants?”

» Hangdewa is a 15-minute bus ride from the district headquarters. Devimaya Sanwa, 45, of the village in Phungling Municipality-9 lost her life due to excessive bleeding caused by placenta retention during childbirth on June 19, 2019.

The ward office and the health post are 10 minutes’ walk away from her house. But the representatives elected to serve the people and health workers paid by the state did not know about her death. Health volunteer Gita Poudel, who works for saving the lives of women and children, was also uninformed about Devimaya despite living so close to her. “I tried to convince her,” said Gita. Ward Chairman Taranath Baral said he had known about the delivery only after the woman’s death.

» This incident happened at Papung Tangkhu in Mikwakhola Rural Municipality-5. Mankumari Sanwa, 36, got into labour in the morning of August 31, 2019. After she delivered a baby at 1 pm, bleeding didn’t stop and the placenta was not released. Mankumari lay unconscious, family members and neighbours gathered but nobody felt it necessary to take her to a health facility or call a health professional. At 4 pm, Assistant Health Worker Chhecha Bhotiya reached there coincidentally. “It was a Saturday and I was roaming with friends. We saw people gathered at the house on the wayside. Then we came to know about the incident,” said Bhotiya. “Bleeding was excessive. Heartbeat had stopped. I found no remedy.”

Ward Chairman Dandu Lama says he learnt about the incident only later. “There is no telephone network in most places of my ward,” said Lama. “I was at the district headquarters then; I did not get information.”

» Thirty-year-old Pasangkhangdu Sherpa of Maikhu in Meringden Rural Municipality-2 died on August 30, 2019. Health workers had given her the delivery date of August 25; she delivered a baby five days later. The cause of her death was that the placenta got stuck for five hours while bleeding continued all the while. Surya Man Okhrabu, chief of the health section of the rural municipality, said she had got her pregnancy examined four times. She had mother, father and brother at home. She had come to her parents’ home from her husband’s house in Phakumwa in Maiwakhola Rural Municipality.

» Lakpa Shangmu Sherpa, 21, of Maikhu in Meringden Rural Municipality-2 lived with her husband. On November 26, 2018, only one of her mothers-in-law and her two children were home as her husband was away. Her labour started in the day and the baby was born at 2 am. Lakpa Shangmu died before 3 am from excessive bleeding. According to Surya Man Okhrabu, chief of the health section of the rural municipality, she had consulted with health professionals in her first two pregnancies. “She did not visit us thereafter. We could not follow up due to a shortage of staff,” said Okhrabu. Two women died in the village in three months due to pregnancy-related complications, he added.

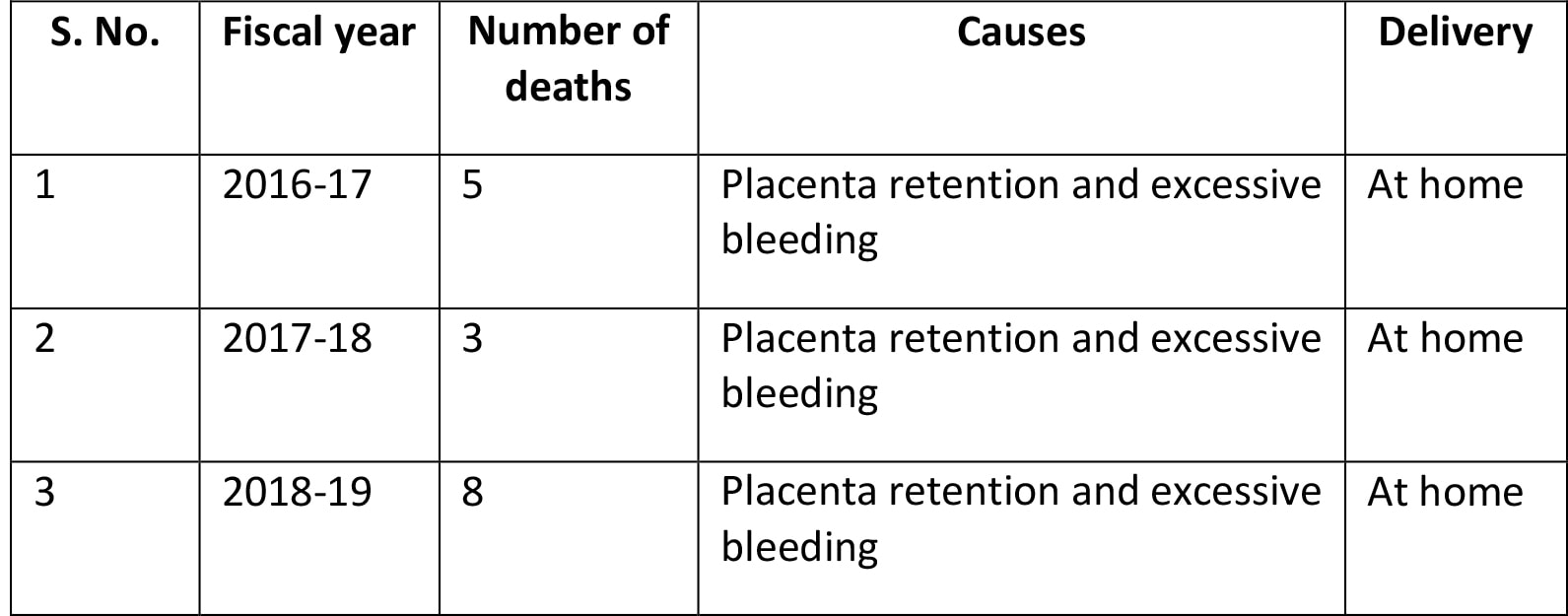

These eight incidents happening within slightly over a year reveal how post-partum women have lost their lives in Taplejung. Most of the deaths were caused by excessive bleeding and placenta retention while delivering baby at home. In some cases, women have died after three days of labour since their families did not take them to a health facility. The number of women dying this way in the past three years is 16. This makes it clear that health awareness in the district is low and the state of women’s health is pitiable.

High risks of delivering at home

Doctors say that delivering at home puts both the mother and infant at high risk. Problems like postpartum haemorrhage and placenta retention are life threatening. “This happens when the uterus does not contract naturally,” said Yolmo. “This is a critical condition caused by bleeding after the baby is born.”

According to gynaecologist Dr Pawanjang Rayamajhi, Oxytosin is injected to stop the bleeding when uterus does not contract for too long. Besides, methods of massaging the uterus are also used. If the placenta is not released within half an hour of childbirth, the condition is called placenta retention. While the placenta is shed in most of the times, it gets firmly stuck with the uterus in some cases. This is one of the causes of post-partum haemorrhage, said Dr Rayamajhi.

According to gynaecologist Dr Pawanjang Rayamajhi, Oxytosin is injected to stop the bleeding when uterus does not contract for too long. Besides, methods of massaging the uterus are also used. If the placenta is not released within half an hour of childbirth, the condition is called placenta retention. While the placenta is shed in most of the times, it gets firmly stuck with the uterus in some cases. This is one of the causes of post-partum haemorrhage, said Dr Rayamajhi.

According to the World Health Organisation, Nepal has the highest rate of maternal mortality after Afghanistan in South Asia. According to the Nepal Demographic Health Survey-2016, maternal mortality rate is 239 per 100,000. According to the data published by the District Health Office Taplejung, the number of women dying due to delivering at home in the fiscal year 3018-19 exceeded the national average.

The Health Ministry has set the goal of bringing down the country’s maternal mortality rate to 99 within four years. The Sustainable Development Goals, to which Nepal has committed, aim for slashing it down to 70.

According to the District Health Office, 3,422 women get pregnant in Taplejung on average in a year. More than 60 per cent of them give birth at home. The number of women delivering babies at home is high in the district due to the lack of awareness, Health Office chief Punya Mani Timsina said.

Dr Soning Lama, chief of the Taplejung District Hospital, said most of the post-partum women die from excessive bleeding. “They deliver at home, and don’t go for the four mandatory pregnancy examinations,” said Lama. “I don’t know if our friends [staff] in villages aren’t working or the villagers are defiant.”

The female health volunteers have crucial roles in the care of post-partum women. They are responsible for encouraging pregnant women to visit health post and hospital; helping the government in national programmes such as vaccination, family planning and controlling diarrhoea and malnutrition; and taking the education, information and communication materials to the ward level. They have failed in their role.

At the district hospital, 583 deliveries were aided by trained professionals in the fiscal year 2018-19. Among them 451 were normal deliveries and 131 surgeries. In the fiscal year 2017-18, normal deliveries numbered 535 and surgeries 162. The figures for the fiscal year 2016-17 were 550 normal deliveries and 124 caesarean. The cost of a delivery at the hospital ranges from 10,000 to 30,000 rupees.

Bijaya Rai, in charge of the nursing section, said those visiting the hospital arrive late. “Women arrive in serious conditions. In many cases, it’s hard to save them while a referral hospital is more than six hours’ drive away,” said Rai. “In many cases, we’ve performed risky operations.”

While women continue to die from delivery-related complications, local governments have been mere spectators. Social leader Narendra Katuwal shares his impression that people’s representatives haven’t prioritized the health sector. “They are focused on opening road tracks and their own perks and facilities,” said Katuwal. “It’s irresponsible to say they had no information when their voters are dying in the lack of medical care.”

He asked both elected officials, who have burdened citizens with tax, and employees paid with taxpayers’ money to be serious. The Constitution of Nepal recognizes health as citizens’ fundamental right. Article 35 of the constitution says: “Every citizen shall have the right to free basic health services from the State, and no one shall be deprived of emergency health services. Every citizen shall have equal access to health services.”

In order to realize the constitutional right, the Ministry of Women, Children and Senior Citizens has introduced a programme for helicopter rescue of pregnant and post-partum women in remote regions. Having rescued 56 people so far, the ministry has set the working procedure for it.

The objective of the programme said to have been operated under the President’s Women Upliftment Programme is “to provide quality healthcare by airlifting women facing risk due to health complications at the time of delivering baby to a specified hospital”, according to the working procedure.

The Taplejung incidents question the effectiveness of the activities and roles of the Women, Children and Senior Citizens Ministry, its Women Empowerment Division and the recommendation committees formed at the local level for rescuing women in critical conditions.

Anju Dhungana, chief of the Women Empowerment Division, said: “This is sad. But we have informed the mayors and deputy mayors. We’ve issued messages from radio and websites. What can we do when information still does not reach us?”

So what could be the ways to save new mothers from health complications in future?

“This is a programme having the spirit of the Women Ministry. But this problem has not been solved with the efforts of the distant federal government solely. Provincial governments, which are closer to the people, should take up the responsibility.”