Why is Kanchanpur being used as a gateway for travels to Dubai and Kuwait? An investigation prompted by this question reveals that women trafficking rings are operating under the guise of foreign employment.

-Pramod Acharya: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

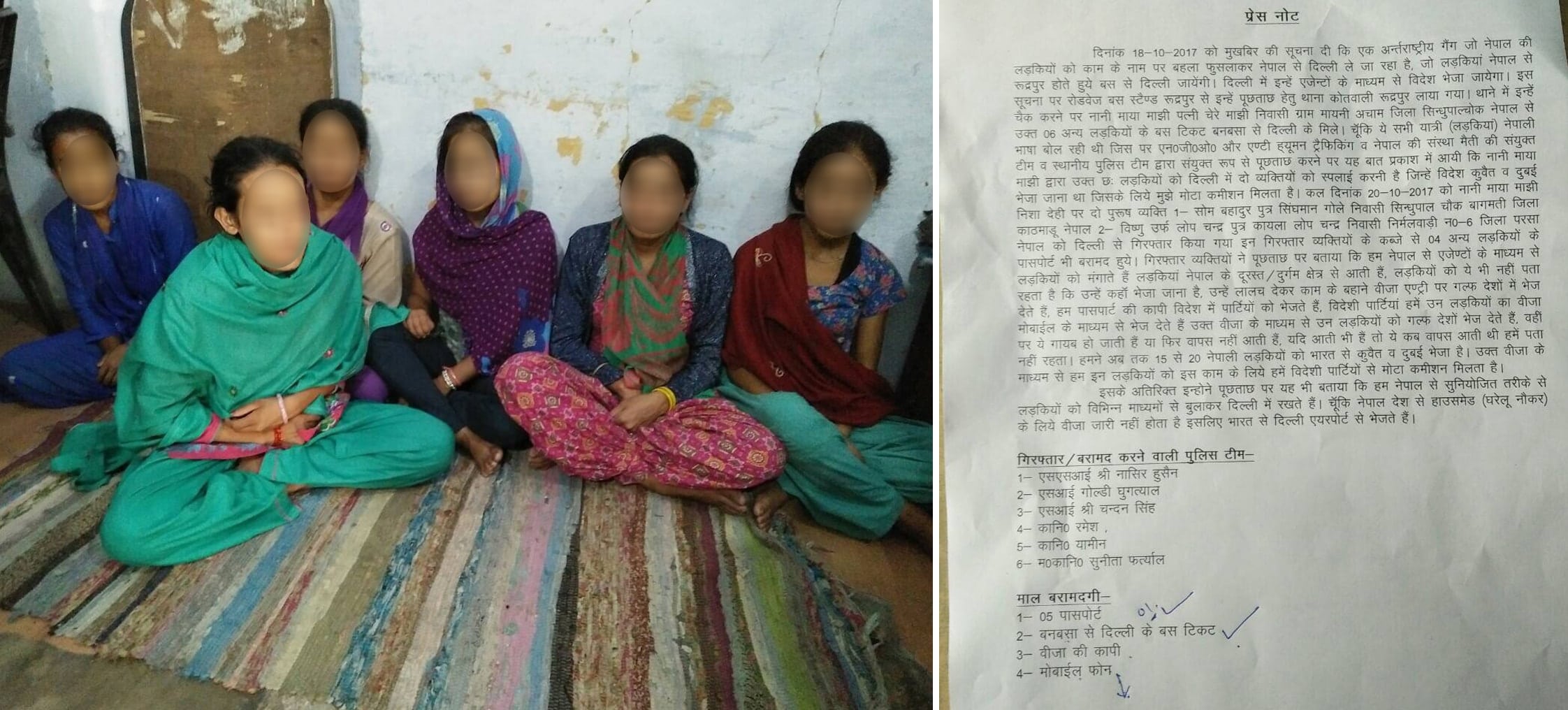

On October 18, 2017, Indian police arrested 6 teenage girls from Sindhupalchok district in Rudrapur, a city in the Indian state of Uttarakhand and handed them over to Maiti Nepal, an anti-trafficking NGO with an office in Kanchanpur. Among the victims was a 14-year-old girl. But her age in citizenship was 19. The teenager from the village of Selang had been lured by a trafficker into the scam so that she could travel to a foreign country.

An 18-year-old girl was also among the six girls arrested by the police, but her age in the citizenship was 20. The teenager from the village of Helambu had also fabricated her age upon instructions from the trafficker. The man behind the scam was Ramesh Tamang, who is from Sindhupalchok district, but now lives in Kathmandu. Tamang enticed both girls’ mothers who granted permission with offers of well-paid jobs in the gulf countries.

But this was not the first case in which girls from Sindhupalchok were trafficked into India via Kanchanpur. In the last two years, 50 girls from Sindhupalchok district have been intercepted at the border and rescued by Maiti Nepal, said Maheshwari Bhatta, the organization’s program coordinator in Kanchanpur district. “This number includes only those girls who were rescued. There could be many others who might have been moved across the border,” she said.

The Indian police released a statement after the arrest of girls who had citizenship and passport with fabricated age as suggested by their traffickers. “In Nepal, teenage girls are recruited to work as housemaids in Gulf countries. Since Nepal doesn’t allow them to apply for a visa for such jobs, they use Delhi’s international airport to make the trip,” the police in Rudrapur of Uttarakhand said in a statement.

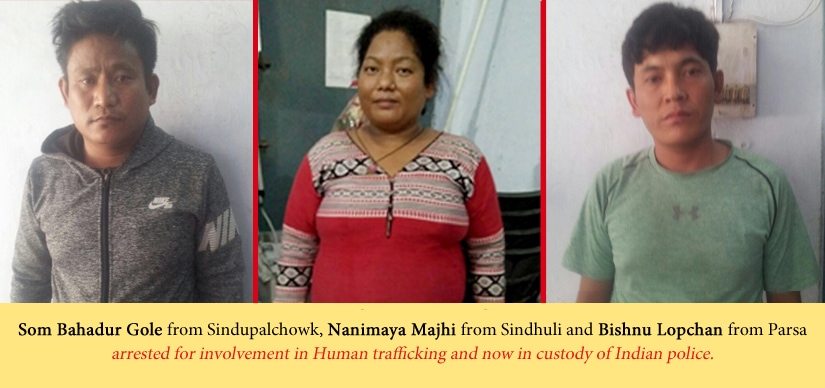

The Indian police has even identified traffickers who smuggled the girls to Gulf countries. The members of the trafficking ring include Som Bahadur Gole (from Sindhupalchok), Nani Maya Majhi (from Sindhuli) and Bishnu Lopchan (from Parsa), according to the Indian police.

The Indian police has even identified traffickers who smuggled the girls to Gulf countries. The members of the trafficking ring include Som Bahadur Gole (from Sindhupalchok), Nani Maya Majhi (from Sindhuli) and Bishnu Lopchan (from Parsa), according to the Indian police.

Both the Indian police and the Nepal Police agree that the method of women trafficking has morphed over the years. In Sindhupalchok, the district with the largest number of trafficking survivors, there’s no complaint registered against human trafficking in the last three years. “That doesn’t mean there was no trafficking activity at all. The fact is that they have changed the tactics of trafficking,” said Bimal Raj Kandel, deputy superintendent of police in Sindhupalchok district. “Human traffickers make sure that they have all the required official documents. They meet all the criteria, which makes it harder for us to identify if the activity is really trafficking or not.”

Earlier, traffickers employed various methods including crossing the border by hiding or handing them to someone at brothel or home and charging money for the travel. But now it’s carried out in the name of foreign employment, according to Kandel. The traffickers would even look after logistics of obtaining citizenship for their targets, who are minor girls.

The word ‘setting’, widely used in foreign employment sector, is characteristic of how the sector operates. In order to operate their network, traffickers make sure that everyone in the authority—the district level officials and people’s representatives—involved in granting permission for foreign employment are on board. After obtaining a recommendation for citizenship from ward office, the girls travel to district headquarters to apply for the national ID at the district administration office. Kopila Tamang (name changed), a 14-year-old in the village of Selang in Sindhupalchok, obtained citizenship as a 19-year-old. While obtaining passport, the trafficker instructed her to use the same age as in her citizenship.

She was rescued by the Indian wing of Maiti Nepal. “Ramesh Tamang (of Sindhupalchok) had persuaded Kopila and her mother to travel to the district’s administration office to apply for the citizenship and passport,” said Maheshwari Bhatta of Maiti Nepal. Assured from their traffickers, the girls and their parents themselves claim that they qualify to obtain the citizenship. “If we question about their age, their mother would say: ‘I have given birth to her so I know when she was born.’ We would have no means to counter further,” said an officer at the District Administration Office (DAO).

The applicants would furnish recommendation letter issued by their local representatives. So despite having suspicion about their age, government officials have no option but to issue them citizenship. “If we feel that the applicants are not honest about their age, we will urge them to wait for a few years before going abroad. But they seem so determined that no matter what, they will obtain it,” said Pitambar Pandey, an administration officer at DAO of Sindhupalchok.

DAO issues fake citizenship

12 years of ordeal

From left to right: Samjhana Tamang from Irkhu, Sindupalchowk, Sommaya Lamini from Simpal, Kavre and Kannchi Tamang from Duwachowr. Photo: Sami, Sindupalchowk

Twelve years ago, a trafficker named Ram Bahadur Bomjan arrived in the village of Indrawati (formerly Simpalkavre VDC) in Sindhupalchok. He said he was looking for women interested in foreign employment. He promised Som Maya Lama a job in Kuwait. Since then, no one knows her whereabouts or whether she is still alive. Her son, Kumar Lama, even travelled to Kuwait looking for her, but he couldn’t find her mother, who had left him when he was 14.

“I was 14 when my mother left us,” Lama, now 26, said. “I went to Kuwait hoping to find her, but I returned home alone.” Bomjon, who is from Helambu, now lives in Kuwait.

Samjhana Tamang, a woman from Sangachok in Sindhupalchok, has been missing for the last seven years. In 2010, she had left for UAE, but her family hasn’t heard from her since then. Kanchhi Tamang, a 52-year-old woman from Panchpokhari Thangpal village, left for Malaysia nine years ago. She is among the women who have left home for foreign employment, but hasn’t returned. There’s no end in sight for the families desperate to find their loved ones.

When she was barely 8, Santoshi Tamang (name changed) was lured by her aunt into travelling to the New Delhi, India with a promise of a job. Her aunt couldn’t find a decent job for her so Santoshi started working as a domestic helper for an Indian family. She was soon subjected to physical exploitation. Traumatized by the experience, she met Yubaraj Lama in New Delhi.

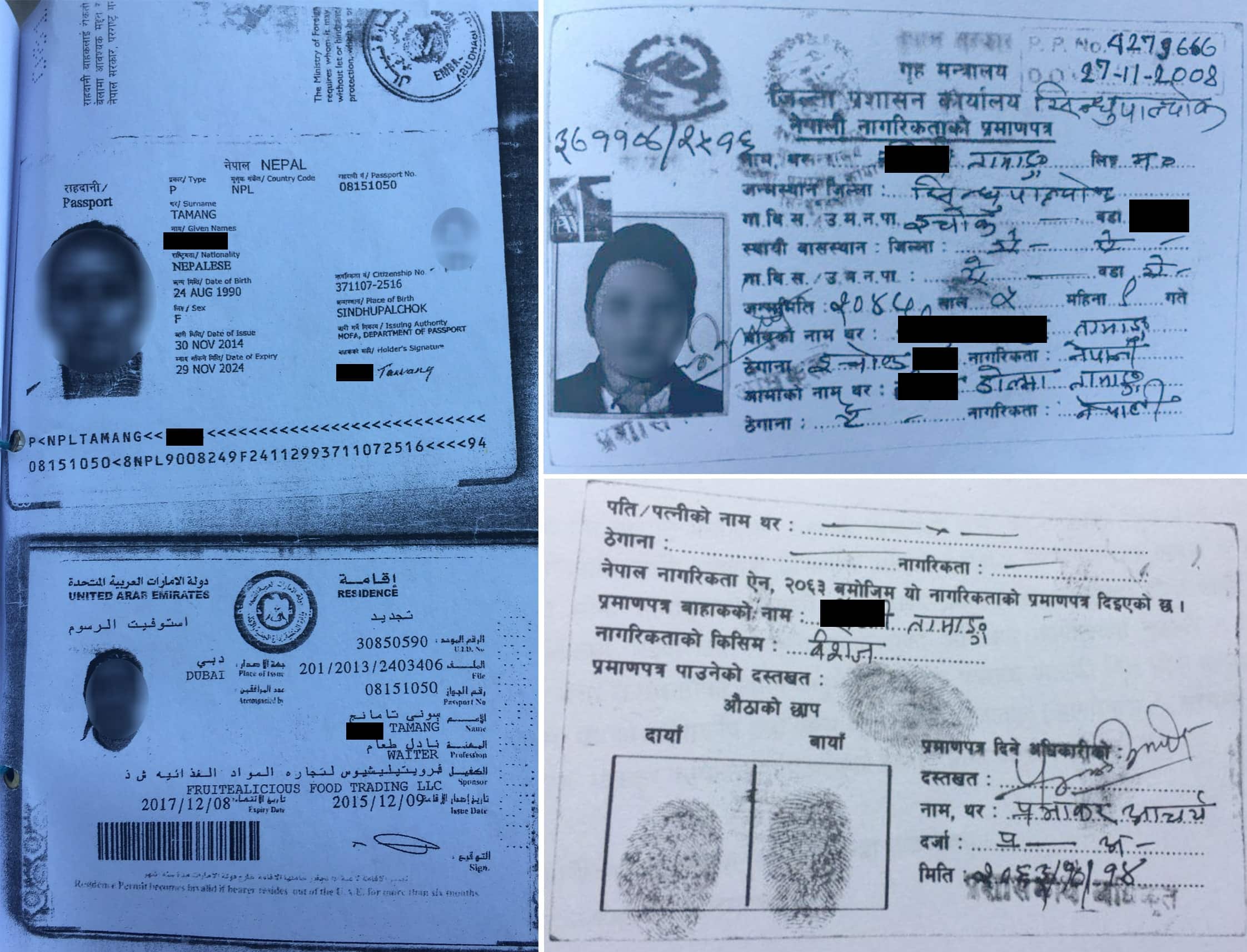

She hoped Lama would finally help her travel to a Gulf country. Indeed, he promised he would help her travel to the United Arab Emirates (UAE). But Santoshi neither had her citizenship nor a passport. In order to apply for her travel documents, Lama and Santoshi made it to Sindhupalchok. Four other young women also joined them in the district headquarters of Chautara, where all of them stayed at a hotel.

“Within an hour, Yubaraj appeared with passport and citizenship for five of us. We were then told to head to Mumbai instead of Delhi,” Santoshi told police on October 9, 2017. Two weeks later, four of them left for Dubai while Santoshi remained in Mumbai. She gave birth to a baby, who was fathered by Lama. After the baby turned 3, Lama sold the baby and sent Santoshi to Dubai, according to her statement to the police.

While returning to Nepal for a vacation after working in Dubai, Santoshi lost her passport in the Indian town of Siliguri. She needed another passport to go back to Dubai. When she applied for a new passport, the Passport Department in Kathmandu required her original citizenship. It also sent the application to the DOA of Sindhupalchok for verification. Her passport turned out to be fake and Santoshi was arrested by police.

In her statement to the police, Santoshi said, “I signed on the application for my citizenship, but I didn’t go to the DAO.” She told police that Lama had brought all the papers at her hotel for her to sign.

Prabhakar Acharya, whose signature appears as an official at her citizenship, never worked at the DAO. Her citizenship number wasn’t found in the database of Sindhupalchok DAO.

But the hologram and the government stamp on the citizenship were legitimate. It demonstrates that traffickers have established a network that stretches from DAO to the Passport Department. “This is not a work of any ordinary person. Yubaraj Lama must be a member of big trafficking ring,” DSP Kandel said. Without the help of a network of associates in every point—DAO, Passport Department, national and international airports—it’s impossible for such a ring to operate, according to him.

The traffickers take extra precaution while handling these various agencies that come in their path. They use original hologram and government stamp on the fake citizenship and passport. The officer who signed Santoshi’s citizenship never worked at the DAO. This makes investigating the officers in cahoots with traffickers and tracking them a tough job. The traffickers produced copies of passports and citizenships with original signature and thumbprint of the bearers. It shows traffickers want it to be seen as credible documents at airports. In order to prevent leak of their collusion, traffickers often kept the documents with them until the last moment and handed them to their victims only before their departure.

Trafficking through mobile phone

Teenage girls and their parents are attracted by promise of a decent job at a foreign country. The traffickers who are at work for an entirely different scheme, never let them know what’s in store for them. Some traffickers even show the girls’ photographs to their potential clients, offering them for exchange of money. Bishnu Lopchan, a trafficker who operates under the guise of foreign employment, has told the Indian police that he would send the girls’ photographs before making a deal with his clients.

Now in the custody of the Indian police, Lopchan’s testimony offers a window into how trafficking operates from Nepal to the destination countries. In his statement to the Indian police, Lopchan confessed of sending Nepali girls’ photographs to his clients so they could choose from a pool of potential victims, according to Maheshwari Bhatta, the head of Maiti Nepal in Kanchanpur, who had seen the statement. “It will ensure me good money,” he told Indian police officers.

This has been corroborated by the statement from Indian police. Lopchan had told police that he collected photographs of girls interested in travelling abroad for work and sent them to his Arab clients in the UAE. In their statement to the Indian police, traffickers have revealed that the sponsors sent a copy of the visa on their mobile phone. “After sending the girls to the Gulf, we don’t keep track of them,” the police recorded the traffickers as saying.

For many decades, India served as the only destination for Nepali trafficking victims. But India is no longer the only country Nepali girls are trafficked to. According to the DAO of Sindhupalchok, girls from the district have been trafficked to Gulf countries including Oman, Malaysia, UAE, Qatar, Kyrgyzstan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Lebanon. DAO officer Pandey said, “It appears that they apply for jobs abroad, but they end up being trafficked.”

For many decades, India served as the only destination for Nepali trafficking victims. But India is no longer the only country Nepali girls are trafficked to. According to the DAO of Sindhupalchok, girls from the district have been trafficked to Gulf countries including Oman, Malaysia, UAE, Qatar, Kyrgyzstan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Lebanon. DAO officer Pandey said, “It appears that they apply for jobs abroad, but they end up being trafficked.”

Sindhupalchok tops the list of districts with the most women trafficked to foreign destinations from Nepal. According to police, the district first recorded a case of trafficking back in the year 2000 of Nepali calendar. Most of the district’s trafficked girls come from the northern areas, according to local authorities. That’s because those villages are mired in poverty and lack awareness on the perils of trafficking. Low police presence in the areas makes it easier for traffickers to operate. Most of the victims belong to Tamang community.

According to statistics from police, the district’s northern villages including Helambu, Ichok, Mahankal, Golche, Gumba, Hagam, Panchpokhari, Banskharka, Balkharka, Baruwa, Bhotang, Gunsa, Thangpalkot are the hotbed of trafficking. “Those who are illiterate and from poor family are more likely to be tricked by traffickers,” said Khyali Singh, a sub inspector at the district police office. “Women from that group are likely to be victims of trafficking.”

Sindhupalchok is second after Jhapa among districts with most female migrant workers in Nepal. In the last seven years, 7770 women have left the district to work abroad, according to Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE). In the current fiscal year, 2020 women left home to work in a foreign country, according to the DoFE. But very few checked about the job before leaving or received any training. In the last two years, only 144 women bound for foreign employment received training, according to Safe Migration Project (SaMi). Women who join foreign employment without seeking information or training often face exploitation from traffickers.

The trafficked women often face sexual abuse and end up being exploited by their employers, according to Rina Shrestha, a coordinator of SaMi in Sindhupalchok. Her office has received cases of women sold into prostitution, who have gone missing, with some of them deprived of their passport and other documents and even death.

In the last 3 years, SaMi has registered 83 such cases including disappearance of five women.

Legal loopholes

The modus operandi of women trafficking has changed. It now operates under foreign employment, but trafficking continues unabated. That’s because there’s no legal framework to address the problem. Neither the Foreign Employment Act of 2007 nor the Human Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act of 2007 addresses this new form of human trafficking. Foreign Employment Act is silent on human trafficking. Human Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act doesn’t clearly describe the act human trafficking under foreign employment as an offense. That’s why there’s confusion on which legislation to follow for cases of trafficking under foreign employment. The traffickers are taking advantage of this legal loophole.

Girls rescued by Uttarakhand Indian Police and Maiti Nepal, Kanchanpur on 1 Kartik 2074 and Press release from Police. Photo: Maiti Nepal, Kanchanpur

The Human Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act defines human trafficking as an act of forcing women and children into sexual exploitation. But it doesn’t include trafficking of women with false promises of foreign employment. The Foreign Employment Act, on the other hand, defines trafficking as an act of cheating. In other words, trafficking is an act of cheating by an individual or a recruitment agency. Under the Act, the offender is subjected to a lenient punishment. A human trafficker faces a 20-year jail sentence, but under the Foreign Employment Act, the guilty is sentenced to 3 to 7 years in jail.

Mohan Adhikari, an information officer at DoFE, said his office is working to amend the Act to clear the confusion. “We have already sent the amendment to Ministry of Law. It must be in pending because we don’t have a parliament now. It will speed up after the elections (for parliament and provincial assemblies),” he said. Roshani Devi Karki, an undersecretary at Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare, said preparations were underway to amend both legislations. Karki said her Ministry was preparing a work plan to resolve the increasingly complex problem of trafficking.

Prabha Ghimire, president of KI Nepal, said that the notion that human trafficking was forcing women into prostitution was preventing authorities from taking action against trafficking under foreign employment. The method of trafficking has changed. These issues– foreign employment, human trafficking, smuggling–must be clearly defined in the law in order to combat trafficking,” she said.

Prabha Ghimire, president of KI Nepal, said that the notion that human trafficking was forcing women into prostitution was preventing authorities from taking action against trafficking under foreign employment. The method of trafficking has changed. These issues– foreign employment, human trafficking, smuggling–must be clearly defined in the law in order to combat trafficking,” she said.

To punish traffickers under the act of cheating is to allow impunity to traffickers, said Manju Gurung, president of Pourakhi, an NGO working for safe migration. “They travel with their own passport, but it’s 100% trafficking,” she said. “They are not given work permit, but are moved across the border using fake documents. This cannot be defined just as cheating.”