While the government tries to influence the economically active group showing that it has been setting up the legal and institutional mechanisms to prevent the country from being blacklisted over the issue of money laundering, it has been providing political and administrative protection for potentially huge financial offences.

Krishna Acharya: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Nepal established the Department of Money Laundering Investigation to probe the acts of presenting illegally acquired property as legal, concealing the real source of such property, changing their form or not disclosing their transaction. The department formed on July 15, 2011 should have been used to probe big offenses and those having lasting consequences. But, as experts point out, the desired outcomes are not being achieved since efforts are being made to use the mechanism as a political-administrative tool, rather than making the required legal and structural arrangements.

Nepal established the Department of Money Laundering Investigation to probe the acts of presenting illegally acquired property as legal, concealing the real source of such property, changing their form or not disclosing their transaction. The department formed on July 15, 2011 should have been used to probe big offenses and those having lasting consequences. But, as experts point out, the desired outcomes are not being achieved since efforts are being made to use the mechanism as a political-administrative tool, rather than making the required legal and structural arrangements.

Two of its latest examples are: the ineffective protest of the National Federation of Transport Entrepreneurs and the episode of government action against medical college operators. In the first month of the Nepali year 2076, the government directed transport entrepreneurs to register under the company law as part of its plans to end the transport syndicates. Defying the call, the Nepal Transport Entrepreneurs’ Federation went as far as shutting down transport services.

Home Minister Ram Bahadur Thapa, then physical infrastructure minister Raghubir Mahaseth, Nepal Rastra Bank Governor Chiranjibi Nepal and department officials had threatened to subject businesses defying the government directive to money laundering investigation and to court cases by freezing their bank accounts. When the business community showed some flexibility following this threat, the issue fizzled out.

The same thing happened with medical college operators. The government had set Rs 3.85 million for Kathmandu and Rs 4.25 million for colleges outside Kathmandu as the ceiling for medical education fees. Medical college operators were found to have been charging Rs 800,000 to Rs 2 million extra from students. The government directed the colleges to either refund the extra amount or settle it in future payments. But the colleges did not obey the instruction.

A study commissioned by the National Vigilance Centre under the Prime Minister’s Office showed that 11 medical colleges had charged Rs 3 billion in total fees. The Department of Money Laundering Investigation received correspondence to take the probe forward based on the report. The department said that it had initiated the process to investigate the property of three generations of the college operators. Immediately, the college operators expressed their readiness to refund or readjust the fees they had charged students extra. This issue faded out too.

It was misuse of law and bargaining on the government’s part to let transport operators and medical colleges off the hook when they relented, after having decided to file lawsuits against them. But an official at the department does not agree. “Illegal income is an issue of investigation any time. You can see the results soon,” the official said.

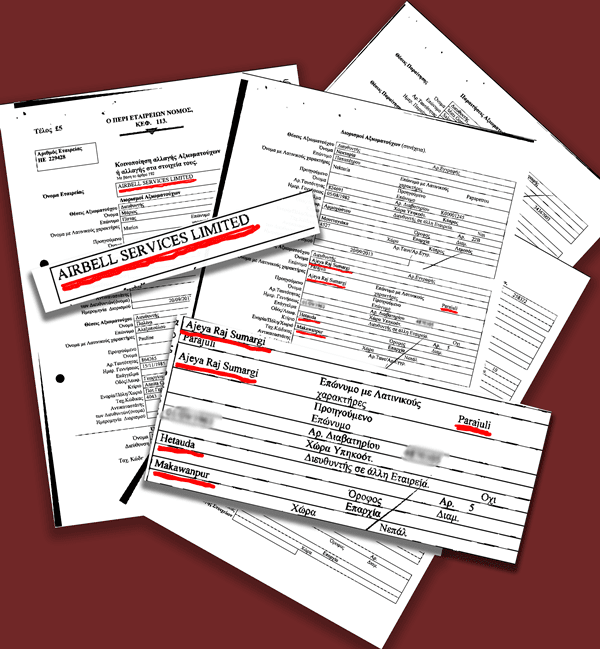

Some cases of money laundering have been going on at the department for years. Businessman Ajeya Raj Sumargi is a case in point. He had repatriated money from a foreign account to his local bank account and claimed it to be foreign investment. The government has been mum for nearly five years about his transaction without obtaining the permission for taking foreign loans, which experts warn will hit the country’s foreign exchange reserves when the investor seeks to take back the stake with dividend.

A year ago, the Centre for Investigative Journalism (CIJ) Nepal and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) revealed with evidence how Nepali businesspeople are engaged in suspicious activities by setting up companies in foreign tax havens and depositing money in Swiss banks. While the Department of Money Laundering Investigation said that it had launched probe into some of the offences, a formal response has yet to come out.

Binod Lamichhane, spokesman for the department, says: “The Department of Money Laundering Investigation is a law enforcement agency. It files cases after investigation based on information received from various state agencies.” One of such agencies is the Fiscal Information Unit of the Nepal Rastra Bank. The maturity of a case depends on the quality of information received from the unit. “We could not pursue cases in the past without quality information. Results will be seen now with the quality in the information coming in,” said Lamichhane.

Progress to show

The Asia Pacific Group (APG) and the Financial Action Taskforce (FATF), which watch over issues of money laundering, in 2020-21 are assessing Nepal’s actions related to curbing money laundering. The government has the compulsion of showing some initiatives in order to avoid being blacklisted by the watchdogs. In order to get positive results in the global assessment of the organizations, provisions barring cash transactions over Rs 1 million, specifying the income source of bank deposits over Rs 1 million, and banks and financial dealing institutions maintaining Know Your Customer details are being tightened. Occasionally, cases are being filed in the Special Court too. For instance, the department charged 48-year-old Samsul Hoda of Kalaiya Municipality-8, Bara on October 30, 2018 under Clause 2 Sub-clause 1 Section A of the International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism.

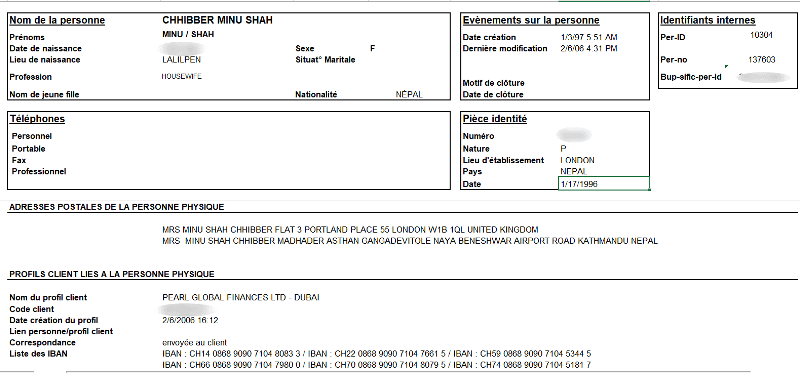

Details of Minu Shah in Swiss Bank personal records of depositors. Source: CIJ files

In general, the anti-money laundering department conducts investigations and files court cases based on the complaints filed or information received from agencies such as the Financial Information Unit of the central bank. But it is difficult to access details on the information shared by the agencies concerned. The number of “suspicious transaction details” passed by the FIU is increasing but the investigations and filing of cases do not match them.

According to the FIU, the number of suspicious transactions from the fiscal years 2015-16 to 2018-19 is 1589, 1053, 877 and 1351, respectively. Among them, the cases needing investigation numbered 138, 191, 312 and 207, respectively. Details of the cases filed show most incidents were not properly investigated or substantial evidence was not found. In the eight-and-a-half years since the department was established, only a total of 57 cases have reached court. According to spokesperson Lamichhane, much of the information shared by the Financial Information Unit is immature. Hence the small number of cases filed.

Poor infrastructure

Why has the department whose performance saves the country from being blacklisted not been effective? Experts point out political interference, inadequate staff, shortage of officials having expertise in investigation, non-cooperation of informer organizations and a huge responsibility assigned to a mechanism headed by a joint-secretary, among the reasons.

Truly, no director general has got the opportunity to serve at the department for long. The department has got 12 DGs so far. Jeevan Prakash Sitaula served the longest period of two-and-a-half years. Three director generals did not get to serve for even three months. Roop Narayan Bhattarai, who was appointed to head the department since it was brought under the prime minister’s office, has been at the helm for nine months.

The role envisaged for the department when it was established was not to see if someone had laundered their ill-gotten wealth. But most of the cases being investigated and taken to court today are about laundering of the money earned from criminal activities. According to a government official who had a crucial role while establishing the department, the structure has been this weak since the political and administrative leadership did not want the department to undertake effective investigation. There’s a shortage of staff skilled in information technology to address the changing nature of financial crimes.

Staffs trained on this issue are required also in regulators of major financial activities such as the Inland Revenue Office and its subordinate offices, Nepal Rastra Bank, Department of Land Reform, the Department of Cooperatives, Stocks Board, Department of Forests and Soil Conservation, police and the Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority. Some believe that results are sought from the Department of Money Laundering Investigation without creating the environment for these agencies to work effectively. “In 99 per cent of the countries, such a department does not exist,” says Lamichhane.

goAML revived

Since it became a member of the Asia Pacific Group (APG) in 2002, Nepal has been trying to demonstrate that it has been working effectively in the field of anti-money laundering. One of its results is the requirement for banks to maintain Know Your Customer details. According to an official at the Prime Minister’s Office, who has been gathering information for Nepal’s international assessment on curbing money laundering, “Right from the start, the work got a wrong direction. The banks should have been able to spend Rs 2 million to Rs 2.5 million on software that stores and retrieves costumers’ basic information such as name, address, occupation and business immediately.”

“When an individual is seen from this database to have been potentially cleansing dirty money through banking transactions, additional information could be sought. If doubts still persisted, cases could have been referred to investigating agencies through the Financial Information Unit of Nepal Rastra Bank,” the official said. “While an estimated 5 to 7 per cent customers involved in shady transactions should have been indirectly monitored, more and more information was extracted from the general public, causing them to harbour negative feelings towards this system itself.”

The banks did not adopt such software but got the customers to fill out paper forms, indulging in a ritualistic business without creating an archive. Such software poses no risk for the banks or anyone doing clean dealings. “This is the wrong direction taken by the KYC. Those transferring wealth illegally were untouched while the public suffered,” the official said.

The central bank tried since 10 years ago to implement this system by issuing directives repeatedly. “The central bank failed due to the influence of some banks having roles in the transfer of illegal wealth. As a result, quality factual data on suspicious transactions failed to generate,” the official said. Asset (Money) Laundering Prevention Act, 2008 provisions fines ranging from Rs 1 million to Rs 50 million for such banks but the Nepal Rastra Bank remained a silent spectator. The issue of implementing the software has surfaced again since the revocation of suspension of Shivaraj Shrestha, the deputy governor of central bank who was charged with not using this provision and non-cooperation on the issue of money laundering.

In a directive issued on December 24, 2019, the central bank has instructed A-class banks to submit reports of limits and suspicious transactions to the Financial Information Unit only through the electronic medium beginning January 15, 2020. “From July 16, 2020, all the financial institutions must compulsorily submit reports only through goAML,” the directive states. Built as conceptualized by the United Nations, the information collected through this electronic system is believed to lead to actual suspicious transactions.

The risk of being blacklisted

The international watchdog APG will have prepared a report in 2020-21 on Nepal’s status on preventing money laundering. Based on the APG’s report and recommendations, the related apex global body Financial Action Task Force conducts an assessment. The FATF closely studies counter-measures based on the 40 recommendations meant to be followed by the member states.

Recommendations 1 to 3 concern legal provisions against money laundering, 4 to 25 prevention measures, and recommendations 26 to 34 are about institutional mechanism and status of implementation. The rest includes an analysis of the situation of international cooperation. While the outcome of future evaluation cannot be predicted now, an official at the Council of Ministers says Nepal’s self-assessment shows the lack of a strong institutional mechanism and a weak state of implementation.

“There’s a risk of the APG recommending to the FATF grey list for Nepal based on our self-assessment,” the official says. “The impacts of being on the grey list include a halt to foreign aid or investments, or a reduction in them, and difficulties in transactions between national and international banks on foreign trade.”

There are foreign cases too. Pakistan is facing similar problems for being put on the grey list. The government has filed corruption cases against former president and prime minister in order to make an impression that it has been working effectively against money laundering. Tunisia also got into the grey list in 2018. On that basis, the European Union blacklisted the country in terms of taxation. Within an hour of the decision, Tunisian central bank governor Chedli Ayari was sacked.

Nepal nearly missed the grey list in 2014 despite failing to set up basic laws and institutional structure. Nepal was spared being put on the list as the APG and the FATF constantly pointed out Nepal’s shortcomings and gave time for improvement. In that process, Nepal had established the Department of Money Laundering Investigation, Proceed of Crime Seizing Freezing and Confiscation Act, amendment to Asset (Money) Laundering Prevention Act-2008 and other tasks including the issuance of several directives from the central bank.

Reining in top officials

Asset (Money) Laundering Prevention Act-2008 was amended to assure international watchdogs that no high-ranking official was outside the scope of action. The revision enables the Financial Information Unit of the central bank or any other concerned agency to issue directives to the department to watch over any top-level citizen or probe their suspicious activities.

Details of Minu Shah in Swiss Bank personal records of depositors. Source: CIJ files

The Bill to Amend Some Nepal Acts issued on March 3, 2019 adds new provisions to the Asset (Money) Laundering Prevention Act-2008 on the country’s high-ranking individuals. The list includes the President, Vice President, prime minister, chief justice, speakers and deputy speakers of the House of Representatives and provincial assemblies, National Assembly chairperson, chiefs of the provinces, ministers, members of parliament, members of constitutional bodies, high court judges, central office-bearers of national political parties, chiefs and deputy chiefs of the district coordination committees, and the chiefs and deputy chiefs of local federal units.

Under the clause, the assigned agency has to keep detailed information about the transactions of such persons and report any suspicions. With this, the government seems to be trying to assure the foreign watchdogs that there are measures in place to take even the President or the prime minister to task for money laundering.

The Council of Ministers has implemented a five-year strategy having passed it six months ago with strong measures related to cash payment, maintaining database of people involved in financial transactions, and their monitoring, investigation and filing of cases. According to the strategy, investigating agencies will now have to conduct also money laundering probe into anyone charged with serious crimes.

While investigating complaints, the Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority, Nepal Police, the Department of Revenue Investigation, the Department of Forests and Soil Conservation, the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, the Department of Foreign Employment, the Narcotics Control Bureau, Inland Revenue Department, the Department of Customs, and the Department of Money Laundering Investigation are also required to probe persons on money laundering.

The strategy mandates ‘one person one bank account’, digital payment of sums over Rs 100,000, and all payments from the state to be made through the banking channel. Other requirements of the strategy involve recording the basic information on customers while opening a bank account via a mobile application or another form of communication technology, inclusion of money laundering in curricula, performance contract with government officials on money laundering prevention, and auditing by the Auditor General’s Office of the efforts at terror financing and money laundering.

The strategy also calls for identifying real individuals who transfer or use illegal wealth by setting up shell companies, and other transactions including fake import-export. The strategy states “using specialized method of identifying the real owner while testing and determining tax and other revenues”.

Did Nepal make these legal and institutional arrangements with the objective of passing the global assessment? Spokesperson Lamichhane says, “We no longer have an assessment for ‘just passing’. We must show the result. Therefore, no task of us is tokenistic, but all essential for the nation.”

One year since the Nepaleaks revelation

Legal provisions, policies and strategies aside, the ‘Nepaleaks’ revelation one year ago showed Nepal’s leadership has only been doing cosmetic work against money laundering while it continues to provide political and administrative protection in huge suspicious dealings. Immediately after the report was published, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli spoke in Parliament in defence of those named in the investigation as having questionable transactions. While the finance minister said he was serious about controlling the movement of ill-gotten wealth, he took no fruitful initiative beyond forming a probe committee.

The Ministry of Finance committee and the parliamentary Finance Committee both lost the opportunities to seriously probe the matter. Addressing a programme in Chitwan, Information and Communication Minister Gokul Baskota had said news reports like ‘Nepaleaks’ had smeared on businesspeople. These statements and activities show that Nepal’s top political leadership has not stopped supporting suspected individuals in matters of illegal incomes, deposits and flight of wealth despite the legal and institutional mechanisms in place.

“Access or influence does not work in money laundering since there is no statute of limitations in such cases,” says Lamichhane, the spokesperson for the anti-money laundering department. “Fifteen years ago, such dealers may have had access to one [powerful person], now it will be another. Therefore, I don’t think assets earned through illegal means last forever.”

However, there are visible results of the government mechanism being even a bit active. In the past two-and-a-half years, foreign direct investment has not arrived from the British Virgin Islands—the third biggest source of FDI in Nepal after India and China. After a halt to the registration of industries from this tax haven, the place of the British Virgin Islands as the source of FDI has dropped to sixth. As no FDI has been received from the islands since the start of the fiscal year 2017-18, the United States and South Korea have come to be among the top four sources of investment in Nepal, data with the Department of Industries shows.

How was this territory that accounted for 45 per cent of Nepal’s FDI until a few years ago left behind? Jeevan Prakash Sitaula, who is currently the director general of the Department of Industries, says: “Investment from such nations has been discouraged with an increase in policy intervention in the activities related to money laundering prevention and the source of suspicious investments.”

According to Sitaula, banks and financial institutions have been cautious about bank accounts before bringing in foreign investment. “Such investment has been discouraged since the central bank started this year a mandatory requirement for accounting of the investment brought in so far and that planned to be attracted in the future,” said Sitaula, who is also a former director general of the Money Laundering Investment Department. “We can’t say all the money that comes from a tax haven is illegal. Since there is a high chance of dirty wealth coming in, such investors have been cautious.”

The Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supply has formed a committee led by a joint-secretary to study about foreign investment whose source is unknown. A meeting of the Industrial Investment and Promotion Board chaired by the industry minister on November 2, 2019 decided to study about illegal foreign investment. As per the decision, a committee led by Joint-secretary Dinesh Bhattarai, spokesman for the ministry, wrote to the Department of Industries and the central bank to gather details about lawful and unlawful investments so far.

A deputy governor of the central bank, the chief agency for preventing money laundering, has been cleared of money laundering charges after investigation. A former chief commissioner of the Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority, which has the responsibility of probing corruption and illegal earnings by government officials and taking action against them, has been accused of committing such offence.

The Department of Money Laundering Investigation has expedited its probe and frozen some property of Deep Basnyat, the outgoing chief commissioner of anti-corruption agency, over the allegations of illegal earnings and money laundering through businesspeople. This is the first allegation of a retired chief of the constitutional commission tasked with controlling corruption engaged in unauthorized gains.

Not just government officials, famed singer Ani Choying Drolma is also being investigated on the suspicion of money laundering. When she brought in 1.649 million US dollars (more than Rs 183 million rupees in the current exchange rate) from Hong Kong without specifying the source, the Department of Money Laundering Investigation and the Financial Information Unit are carrying out their investigations.