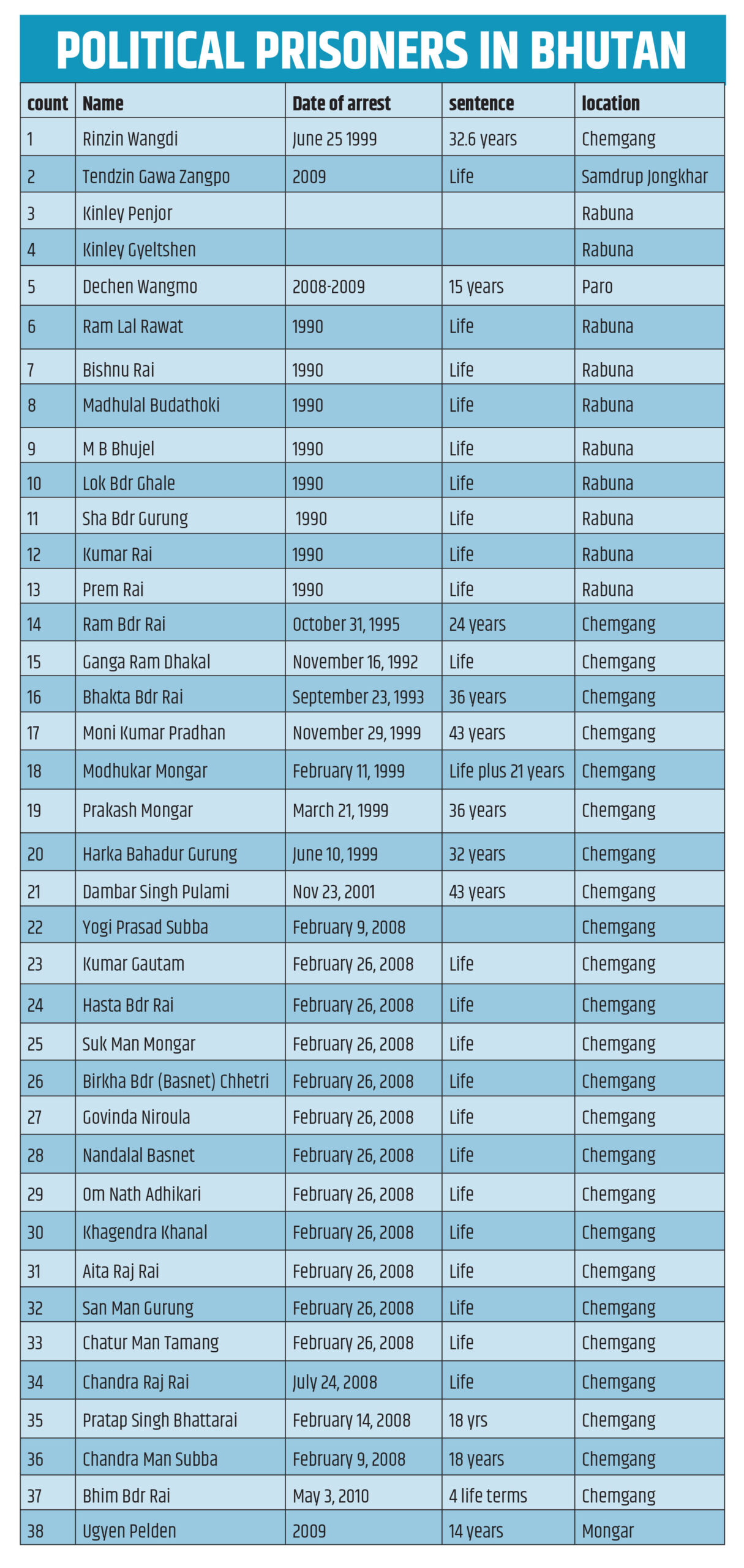

Many Bhutanese refugees have been rehabilitated to third countries but they have not heard from their children languishing in jails. While Bhutan bans ICRC from entering the jails, the list of the prisoners is scheduled to be released from New York this week.

Devendra Bhattarai |CIJ, Nepal

There are two dates that remain indelible in the mind of Dambar Kumari Adhikari, 62, who is living a refugee life at Jhapa’s Beldangi camp—April 12, 1992 and September 1, 2017. On the first date, she was evicted from her native Dagana in Bhutan; the latter, she met her only son at the country’s Chemgang jail.

For Dambar Kumari, the eviction and the subsequent imprisonment of her sons is a distant past. These days, she is more concerned about whether she’d be able to meet her son again. Her son Omnath, 39, has been languishing in the Chemgang jail for over 15 years, since February 26, 2008.

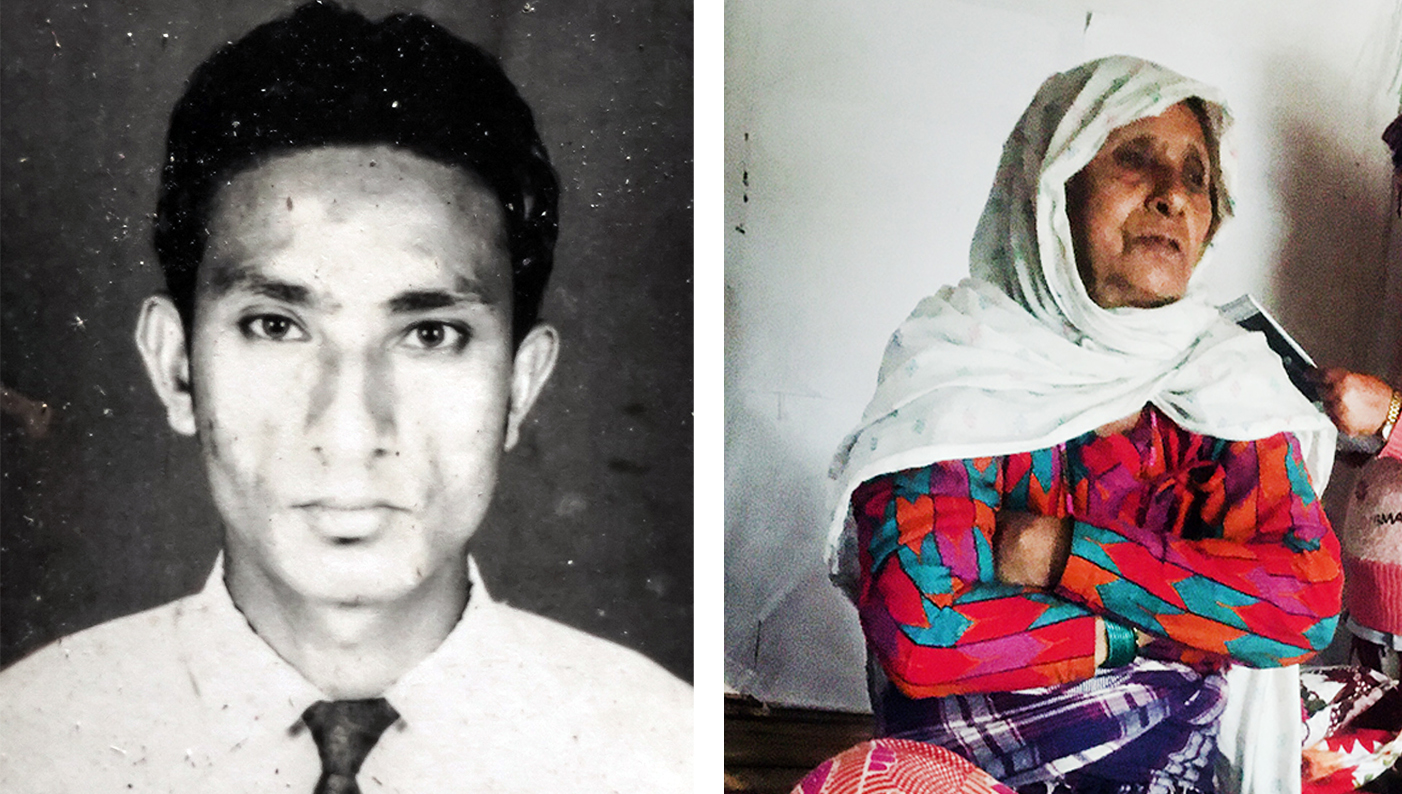

(L to R)Chaturman, currently in prison in Bhutan, his father Suk Bahadur and mother Aitimaya Tamang, currently in the US.

“I can barely stand the pain of knowing my innocent son was jailed and that we are not allowed to meet him,” Dambar Kumari, who the CIJ met at a hut in Bange Chautari, Beldangi, said. “I met him four years ago. Now I don’t know whether he is still alive or dead.”

Three months ago, a person she knew in Bhutan told her that her son was taken to a government hospital in Thimphu. She wondered whether it was because he contracted Covid or some other disease. To find out, she reached the offices of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Kathmandu and Biratnagar. But she had to return without any information.

While previously, Bhutanese government would allow ICRC representatives to visit the prisons once or twice a year, for the past four years, it has become stricter, citing Covid-19 and other security reasons. “We haven’t received a letter of permission from the Delhi headquarters,” an ICRC official in Kathmandu said. “We only know that there’s a ban in place.”

Dr DNS Dhakal, a lecturer and rights activist who lives in Jhapa’s Chaaraali, says that these days, it’s difficult to even step into Bhutan. “It’s said that Bhutan and India have an open border, but ‘stamping’ is necessary for even the Indians,” Dhakal said. “They charge Rs10 for entering the border and Rs1,250 to stay the night inside the country. Meanwhile, authorities have been disregarding Aadhaar or ration cards and making voter id cards mandatory.”

Children at jails, parents abroad

Suka Bahadur Tamang, 65, and his wife, Aaitamaya, 55, live in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. But when they got news that their eldest son Chaturman was jailed in Chemgang, they were still in Beldangi. Chaturman’s brother, Pasang Dorje, says that his parents had visited his father and sister had visited his brother in jail in 2014. “After that, we came to the US,” Pasang Dorje told CIJ over the phone. “It’s been over eight years and we know nothing about him.”

Thirty-nine year old Chaturman, with an ICRC registration number 000454, is unmarried and serving a life imprisonment.

(L to R)Omnath Adhikari in Bhutan prison and mother Dambarkumari Adhikari, currently in Beldangi refugee camp.

Bhagirath Gautam, 86, and his wife, Ranamaya, 76, also knew of their son Kumar’s imprisonment when they were still at the refugee camp. They met Kumar at Chemjong in 2012. “After that, seven of us family members came to Canada, while my brother Kumar remained in Chemjong,” Laxmi Gautam, Kumar’s elder brother, told CIJ from Canada over the phone.

Laxmi said that he knew of his brother’s imprisonment on charges of ‘treason, terrorism and political hooliganism’ belatedly. Kumar was on a journey to Siliguri then. “What offense he committed, we never knew,” Laxmi says. The elderly parents were dejected and amid that, they came to a strange world in Canada.

“I have written to agencies such as ICRC, Amnesty International and others on behalf of my parents,” Laxmi said. “I have even written to Canada’s prime minister and foreign minister, asking them to speak out about Bhutan’s political prisoners and human rights violations. But I haven’t heard from them.”

Prem Bahadur Rai, 67, currently lives in Australia’s Tasmania. But his son Hasta Bahadur has been languishing in Chemgang jail for 14 years, as a political prisoner with ICRC registration number 00456.

The Rai family, evicted in early 1990s, were living as refugees in Beldangi camp. After their attempt to return to their country failed and were instead forced to move to a third country, Prem Bahadur reached Tasmania with his daughter Harimaya in 2012. “Before we came here, my father would regularly visit my jailed brother, but after there was no certainty of his release, we came here,” Harimaya said over the phone. “My father was married while in Beldangi and had two children. Later, my sister-in-law remarried and moved to Canada. My brother remains in jail.”

While Prem Bahadur says one shouldn’t lose hope until one is alive, he doesn’t know whether his son is dead or alive. Harimaya said that they haven’t known anything about her brother for the past eight years.

Until a few years ago, the ICRC and other international agencies would let the families know that prisoners like Omnath, Chaturman, Kumar and Hasta Bahadur were alive. But now, the only source of that knowledge is a list of proof published from New York in the US.

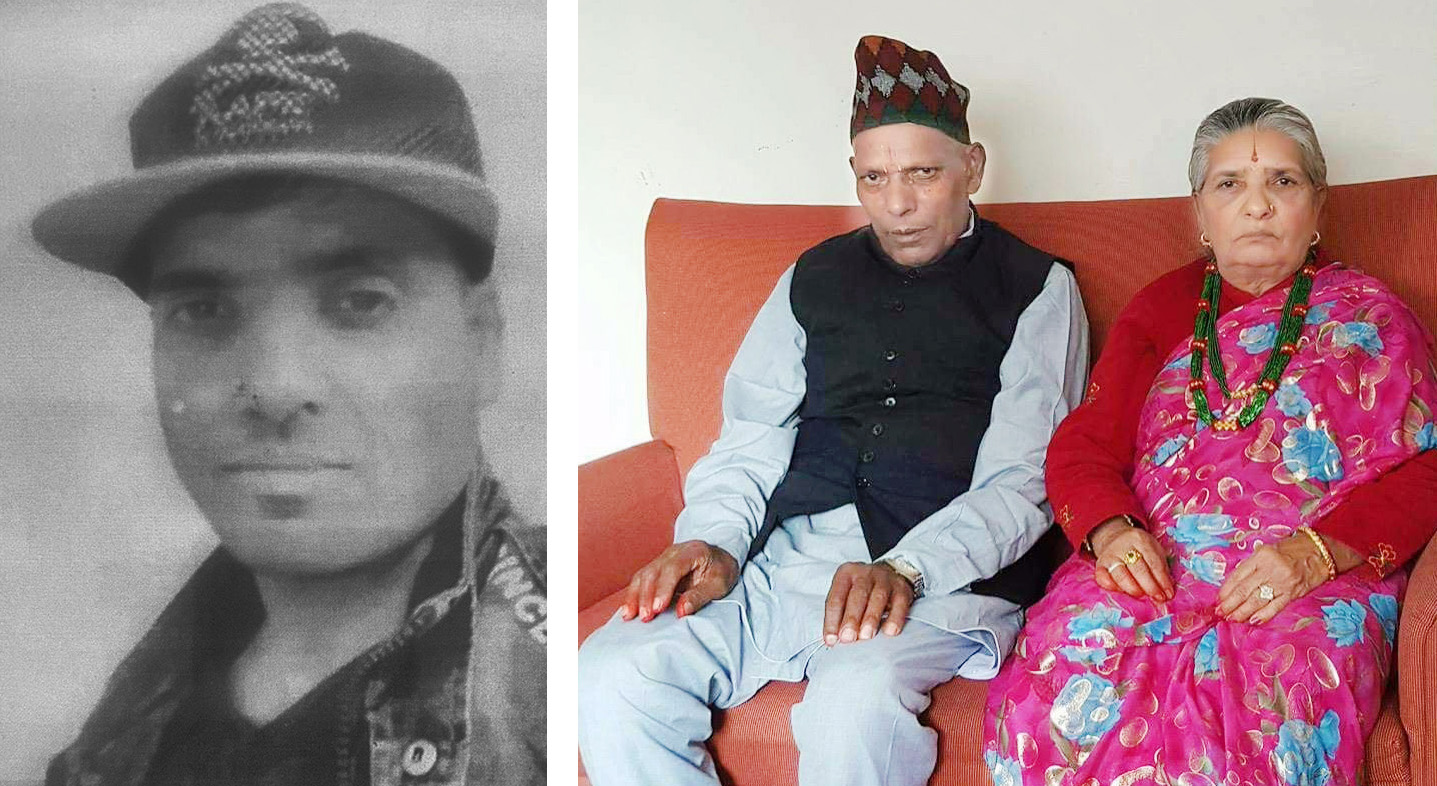

(L to R) Hasta Bahadur is incarcerated in Bhutan, and his father, Prem Bahadur Rai, is currently living in Australia.

Bhutan, which maintains a democratic posture in the world at large, has imprisoned over 50 such youths since 1990 in the name of carrying out treasonous political activities. Agencies such as the ICRC and Amnesty International are aware of this.

The American NGO Human Rights Watch is now preparing to release the list of political prisoners and set off a discussion about the injustice meted out to them by the Bhutanese state.

Meanwhile, in the coming week, a proposal that states that the ‘Bhutanese state is responsible for the ethnic cleansing of over a hundred thousand citizens’ is scheduled to be registered in the first meeting of the US senate. The proposal will set off a discussion about the injustice and human rights violation perpetrated by the Bhutanese state.

Ram Karki, who has been advocating for the unconditional release of the political prisoners and rehabilitating them with their families, has raised his voice at platforms such as the International Criminal Court, Hague, and the United Nations. But he says that the world at large is still ignoring the issue, lulled as it is by Bhutan’s ‘happiness index’ and false promise of democracy. “The recent Geneva human rights assembly too ignored it,” he said.

A long wait at the camp

In 1992, Ganga Lal Gurung was evicted from Bhutan and he arrived in Nepal by way of India along with nine of his family members, including his parents and siblings. In the first week of February 2008, his brother Sanman had reached the bordering village of Jayagaun through Siliguri in India. The family doesn’t know where he went afterwards, until the news of Sanman’s imprisonment in Chemgang reached Ganga Lal. It turned out he was jailed, including others refugees such as Omnath Adhikari, Birkha Bahadur Chhetri, Hasta Bahadur Rai, Chaturman Tamang, Nanda Lal Basnet, Govinda Niraula, Aaitaraj Rai, Khagendra Khanal, Sukaman Magar and Kumar Gautam.

Sanman’s parents waited at the camp for a long time for his return to no avail. Only after they requested the ICRC were they allowed to meet Sanman in Chemgang jail. After that visit, Sanman’s parents were rehabilitated in Australia. His brother Ganga Lal, however, awaited him at Beldangi camp.

(L to R) Kumar Gautam in Bhutan jail and hi father, Bhagirath and mother Ranmaya gautam, are currently living in Canada

In a 2016 visit, Sanman had asked Ganga Lal to wait for him at the camp so they could both move abroad together. After Sanman told him that his release was uncertain, Ganga Lal reached Australia only a few months ago.

The story of Narapati Khanal, 60, and his wife, Deumaya, 66, who live in Hut number 272 at Beldangi-2, is equally tragic. Their second son Khagendra was also imprisoned at Chemgang in 2008 while he had visited Bhutan with Bhakta Bahadur and Sanman.

“My brother is kept at Chemgang’s block-4,” Khagendra’s younger sister Umata Devi says. “My father and I have visited him at the jail four times already. My brother asks us to move abroad and keep his documents at the camp. But my parents are reluctant, so we are staying here.” The Khanal couple’s two sons have each moved to Australia and Canada.

But as time wore on and their neighbors at the camp moved abroad one after another, the Khanal couple were also pressured to do likewise. While previously they had waited for Khagendra, now they have also moved abroad only a few weeks ago. They have now moved to Canada leaving behind Khagendra, who is registered by ICRC as 000464, at the Bhutan jail.

Families of inmates Omnath Adhikari (ICRC 000455), Bhakta Bahadur Rai (000225), Khagendra Khanal (000464), Ganga Ram Dhakal (000188) and others are still awaiting at the Beldangi camp. But the ICRC hasn’t been able to furnish details about those who disappeared from this Damak-based camp, such as Lok Nath Acharya, Kul Bahadur Basnet and Chengum Dukpa, are still unknown.

After Bhutan disallowed even the ICRC to enter the prison, the refugees can’t ask anyone about the status of their relatives now. In mid-June last year, Bhutanese government’s mouthpiece Kuensel reported that one Dambar Singh Pulami, who was imprisoned for 22 years, was admitted to a Thimphu hospital after he became seriously ill. He was being treated at the ICU ward, the newspaper reported. After that news, the global movement to release Bhutanese political prisoners issued a note that said Pulami was being treated at Thimpu-based Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital. Pulami’s family, including his wife, have already relocated to the US.

Pulami, who was evicted in 1992 and arrived in Jhapa’s Timai, was arrested from a Bhutan-India border point in 2001. He is a political prisoner with ICRC registration number 00397. Mani Kumar Pradhan (ICRC 000385) is another such political prisoner who has been given a 43-year jail term.

The hospital-admitted Pulami’s status and whereabouts remain unknown so far.

In April last year, Chhewang Rinjin, a Bhutanese rights activist and leader of Druk National Congress, and five other Nepali speaking Bhutanese prisoners were released from Chemgang jail. It was reported that the Bhutanese government also released Kharka Bahadur Mogar, Balaram Chamling, Naindra Prasad Khulal (Kharel), Ghanashyam Gurung and Ram Bahadur Khulal, all of whom were arrested in 2008. But their whereabouts remain unknown even after they were released.

The latest list mentions that the political prisoners are kept at Samdrup Jongkhar, Rabuna, Paro, and Mogar prisons alongside Chemgang.

“Bhutan has earned publicity as a democracy and a happy country in the world at large but it has failed to even uphold basic human rights,” Tek Nath Rijal, a Bhutanese human rights activist, says. “Even countries like the US and the UK that consider themselves the champions of democracy, human rights and freedom have kept mum about Bhutanese state’s violations. It is surprising why even Nepal has been unable to question gross human rights violations of the Bhutanese state from platforms in Geneva and New York.”