Local governments introduced the Barghar Act to institutionalize the traditional leadership system of the Tharus, but it has instead posed new challenges to the community’s traditions of self-governance and mutual support.

Krishna Raj Sarbahari | CIJ Nepal

On January 9, 2021 Bardiya District’s Barbardiya Municipality passed a ‘Barghar Act’. The Act, which was introduced to regulate the Tharu community’s traditional ‘barghar’ (leadership) practice, was the first of its kind promulgated by any local level government in the country.

“The Barghar system should be understood to refer to the traditional systems and organization of autonomous self-government practiced continuously since time immemorial by the Tharu community according to their customs and customary laws,” the Act says.

Participants of ‘Magh Festival 2024’ at Barbardiya’s Ward 6.

Barghar refers to both the social system and the local leaders informally elected to lead the village’s social, cultural and religious life. This system, which has been in practice at the Tharu community level for hundreds of years, now faces new challenges following local governments attempts to codify it into law.

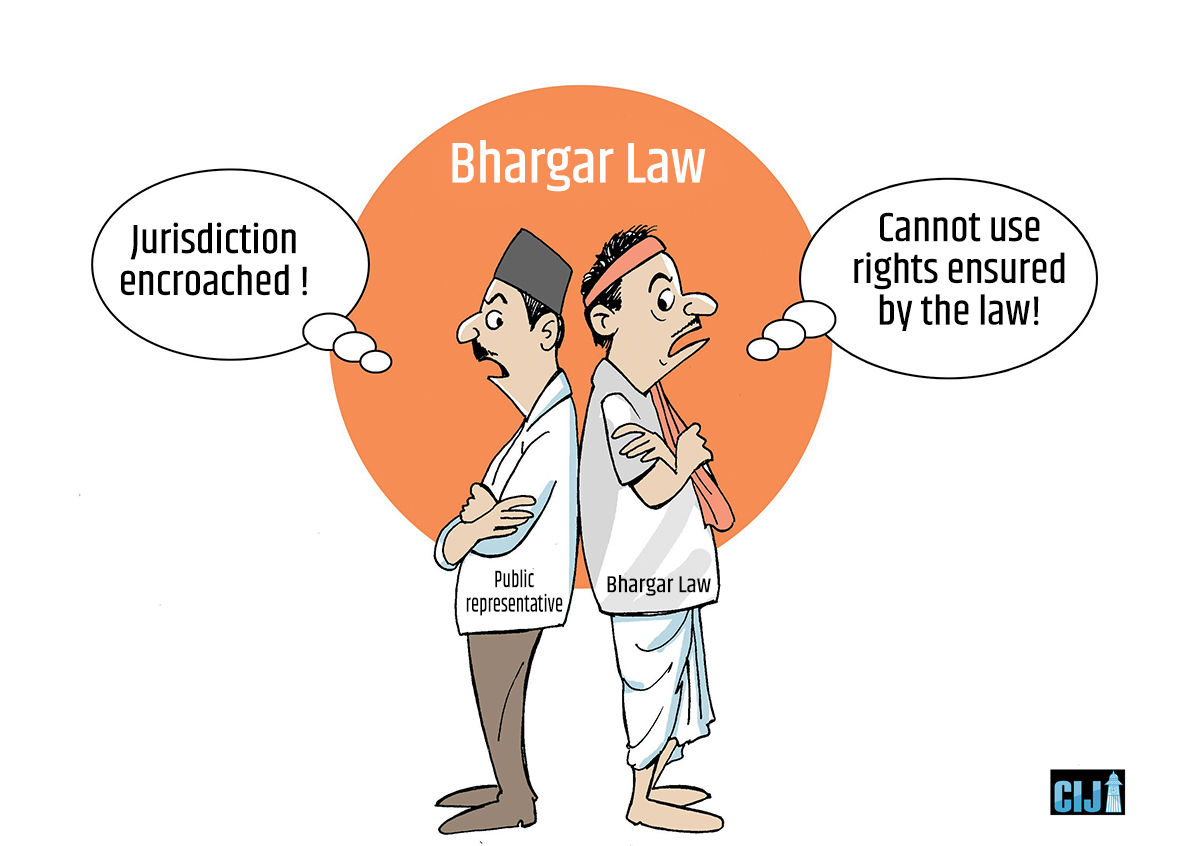

Elected local representatives are afraid that conflicts might arise between them and the barghars while the barghars complain that they haven’t been able to exercise the rights given to them by the Act.

According to the Act, policies at the village level will be implemented by a consumer committee constituted through a jutyahla (a discussion meeting) led by a barghar. The Act also says that a monitoring committee, led either by the barghar or a person designated by a barghar-led jutyahla, will supervise and monitor the plans and policies of the local government.

However, Kaliram Chowdhury, chair of the Barbardiya Barghar Network, says that the local government has not even informed most barghars about the Act’s provisions, let alone form such a consumer committee. “Initially, some barghars were invited to carry out monitoring work but now, they’re being completely ignored,” he said.

The Act also provides for the participation of local people’s representatives in the selection of barghars and the participation of barghars in meetings of the local budget and program formulation committee, and meetings that approve the budget and programs. However, due to non-compliance with this arrangement, plans and policies selected by the villagers through the barghars have not been prioritized by the municipality.

People’s representatives as impediments

Elected people’s representatives are not pleased with the presence of barghars in the meetings of the budget and program formulation committees, according to Kaliram, who contested the local level elections for ward chair in 2017 and 2022 as a Maoist Center candidate. He lost both times. However, as chair of the barghar network, he began participating in the municipality’s meetings. Ward chairs weren’t pleased with Kaliram’s presence, given that he had lost the election. They protested, leading Mayor Chhabilal Chaudhary to stop inviting Kaliram to the meetings.

Mayor Chhabilal admits that that he was unable to continue inviting Kaliram to the city council meetings, despite having already invited him several times in the past, due to protests from the ward chairs. “If the barghar was just a social figure, it would’ve been easier to invite him to the council meetings. The other ward chairs are uneasy because he is an electoral rival who lost.”

Barbardiya Municipal Barghar Network President Kaliram Chaudhary.

Kaliram disagrees with the mayor. “The Act specifically mentions that the chair of the municipal barghar network can participate in the city council,” he says. “How can the mayor prevent me from attending council meetings when I was chosen as coordinator by barghars from all over the municipality?”

Similarly, barghar Bam Bahadur Tharu of Fachkahwa village, Barbardiya-11, hasn’t been invited to take part in a single meeting. For the past year, he has had one demand from the municipality and the ward – pave the maruwa (a worshipping space for the collective village deity). But his demands have fallen on deaf ears.

Durga Tharu, the former mayor of Barbardiya Municipality who instituted the Barghar Act, says that the legislation was promulgated on the advice of many barghar leaders who had long complained that they had been neglected by the municipality despite contributing directly to its development.

“We were the first to promulgate an act to allow barghars to participate directly in local governance; now, the number of municipalities that have issued such acts is over twenty,” says former mayor Durga.

However, the very municipality that first introduced the law has failed to implement it. “A Tharu community cannot function without a barghar, but it is sad to see implementation neglected despite most elected representatives belonging to the Tharu community,” says Durga.

Conflict between the barghars and elected local representatives appears to have increased since the promulgation of the Act. Elected officials believe that the barghars are attempting to encroach on their authority while barghars believe that little will be gained by relying on civil servants and that one needs develop one’s own community.

“It would be enough if the local level gave them their due respect and included them in the planning of the city’s policies,” says Durga.

“A Tharu community cannot function without a barghar, but it is sad to see implementation neglected despite most elected representatives belonging to the Tharu community,” -Durga Tharu, former mayor, Barbardiya Municipality

Ekraj Chaudhary, who is assisting in the legal organization of the barghar system, does not envision implementation of the Barghar Act anytime soon. According to Ekraj, in the eyes of the local people’s representatives, the current Barghar Act is ‘revolutionary’ and a threat. Problems are bound to arise when populist laws are promulgated quickly instead of attempting to figure out how to make the barghar system more active, creative and result-oriented, says Ekraj.

. Barghar meeting at Sutaihya village, Baijnath-3, Banke.

Reform-oriented barghars

Depending on the place, barghars are also known as mahtawa, kakandar, pradhanwa and bhalmansa. But barghar has lately become the most popular form of address. Barghars lead all kinds of social, religious, cultural and judicial work in the village. Whether it is resolving a quarrel or dispute or taking a decision to build a road, a bridge or a dam, the barghar bears responsibility. The barghar is also responsible for deputing volunteers for weddings, leading pujas at the local community temple, and conducting funeral rites.

Earlier, barghars led their own villages and communities but after the promulgation of the Barghar Act, barghars from the ward to the municipal level have started to come together. An example is the unity of all barghars in Bardiya’s Bansgadhi Municipality.

This January 2, a jutyahla of barghars from 45 villages in the Bansgadhi urban area was held at the premises of the Gurwawa FM radio. No one went home until the likhandaria (the rapporteur) announced the decision of the meeting.

Barghar selection meeting (Khyal) at Jayanagar ‘Ka’, Barbardiya-6.

In the villages of West Tharuhat – Dang, Banke, Bardiya, Kailali, Kanchanpur, and Surkhet – each village holds a khyal (a comprehensive meeting of the entire village) in the first week of the Nepali month of Magh (January-February). The khyal establishes the rules according to which the village will function. The khyal held in Bansgadhi took some important decisions regarding the establishment of order in Tharu villages. Regarding weddings, it was decided that no more than six people could be invited to the engagement, no more than 51 people to the groom’s wedding party (janti), no more than 25 to the sending of the bride (pathlahari), and that all feasts would end before midnight, with no DJ for the party. The meeting also took decisions ranging from ways to keep the village clean to the prohibition of child marriage, forced marriage, and polygamy, which are all already prohibited by law. All barghars in Bansgadhi municipality agreed to be frugal and work to preserve their culture since Tharu customs were disappearing amidst expensive outside influences.

Khyals held in other areas have taken similar decision aimed at maintaining social order. In Sathariya, Bansgadhi-6, a khyal decided to ban alcohol at all weddings and parties in the village, imposing a fine of Rs 1,000 on anyone not complying, and a further fine of Rs 5,000 on public intoxication.

Similarly, according to barghar Tingu Tharu of North Bakhari village in Bansgarhi-3, barghars would often choose a few villagers to work in the fields during paddy plantation and harvest as unpaid laborers. That practice has been put to an end. During pujas, the fiftieth chick and piglet had to be offered to the gods. Now, barghars, in collaboration with teachers, have established a tradition of offering sweets instead of animal sacrifice. “Under the leadership of barghars, the practice of offering sweets instead of sacrificing animals has taken root in our village. It appears that the gods can be satisfied even with vegetarian food,” says Tingu.

Security guard Ramsundar Tharu verbally shares information in 25 toles (sections) of Lamkiphata, Barbardiya.

In Bardiya’s Gulria-1, a khyal held to choose a barghar also decided that each household would contribute a half kilo of paddy per kattha (about 338 square meters) of land to build a school. Barghars thus seem to also have taken up responsibility for education in the villages.

Some villages divided, some made aware

When Barbardiya Municipality began issuing identity cards to barghars and providing them with amenities like Rs 300 a month for communication expenses, there was a rush among villagers to become barghars. Discussions were also held to provide bicycles to barghars.

Nandaram Ghimire is the barghar for 18 households in Bhimsen Tol, Barbardiya-6 while Sita Ghimire is the barghar for 42 households in neighboring Pragatipur. Previously, the two neighborhoods were one but after disputes arose between the father-in-law and daughter-in-law, they decided to split the neighborhood into two and become barghars on their own. Jaypur village in Barbardiya-6 was also split due to infighting among villagers to become barghars. After a conflict with the existing barghar, Antaram Tharu declared one neighborhood Jaypur ‘B’ and himself the barghar. Jaypur ‘B’ only has 22 households, when the Barghar Act states that one barghar should look after a minimum of 50 households.

However, amenities promised by the Barghar Act were shortlived. The municipality no longer provides 300 rupees to the barghars for communication. Without any perks, no one from Jaypur ‘B’ was willing to become a barghar. Subsequently, a barghar was chosen randomly through a lottery, recalls the barghar of Jaypur ‘A’ Krishna Prasad Chaudhary.

But not all barghars are in it for the perks; many genuinely want to contribute to social development in their villages. On January 19, Mahendra Chaudhary, the barghar for Banke District’s Sutaihya village, Baijnath-3, presented the expense report for the previous year to the khyal. But according to Krishna Chaudhary, who was present at the khyal, expenses of around Rs 65,000 were not transparent and thus, the khyal decided not to endorse the expense report. It was only after a decision was made to explain all expenses, no matter how minor, at the next meeting that the khyal moved forward.

At the same khyal, teacher Narayani Choudhury suggested that barghars should conduct special programs to revive the Tharu language as Nepali and English words were entering the speech of Tharu speakers. Since barghars manage wedding feasts and death rites. Sumati Choudhary suggested that the practice of women going into the forest to collect green leaves for such feasts should be put to an end and that plates should instead be provided through money raised from fines. Fifty percent of the 68 people who participated in the afore-mentioned khyal held at Sutaihya village, which has 51 households, were women.

The experience of non-Tharus

The barghar system is an integral part of the ‘Save Tharu Culture’ movement. In some villages, barghars have been selected from non-Tharu communities, but these non-Tharu barghars do not appear to prioritize preservation of Tharu culture.

Lekhnath Bhusal of Gulra village in Barbardiya-6 was a barghar for about four years. He says it was not difficult to carry out activities related to Tharu culture as there was an 11-member barghar committee that included a primary barghar and an assistant barghar. Even so, he said that he was not able to properly name the Tharu community’s religious practices, festivals, dances, and songs as he did not take part in them himself.

Bhosu Tharu, who was the barghar in Gulra for many years, is now a ward member. In his experience, non-Tharu barghars are not appropriate agents to preserve Tharu culture and traditions. He related how Krishna Ghimire, who is not a Tharu, was selected as an assistant barghar but had to resign in just four months as he did not know how to conduct the Tharu community’s religious practices.

Barbardiya Municipality’s Mayor Chhabilal Chaudhary (left).

“You can’t become a barghar just because you want to,” says Phularam Tharu, the barghar of Mahadev village in Bansgadhi-3. “The entire village needs to trust you. If your relatives make a mistake, you need to be able to punish them too. You have to hold regular religious ceremonies in the village and have the ability to welcome guests with respect when they visit.”

Many expenses, little income

In the Tharu language, ‘bar’ means big. ‘Barghar’ literally means the man from the big house. Phularam Tharu’s grandfather had a big house in the village. Thus, his grandfather and father successively led the village for decades. Phularam himself has been the barghar for the last seven years. However, the big house has split. Phularam’s closest cousins are now divided into 27 houses while his relatives make up 40 households. Still, Phularam’s extended family has been decisive in selecting the barghar of the village.

But barghars are no longer big men from big houses. Most barghars are unable to discharge their duties without some support from the community and the local government. Bhosu, who quit being a barghar after becoming a ward member so that others could take part in running the village, says, “Apart from occasional allowances, the work of a ward member, just like that of a barghar, is also voluntary. Both jobs are difficult for those who are not interested in social service.” He has demanded that the local level provide some facilities to barghars to ease their work. “Ten kilos of paddy are collected from every house for the village chowkidar (watchman) and 20 kilos for a guruwa (healer). Barghars don’t get any of that.”

Former Barghar of Gulara village and Ward Member Bhosu Tharu, Barbardiya-6

The 100 households of Machhagadh village in Bansgadhi-9 collect five kilos of paddy each annually to pay the barghar a salary but still, few people are willing to become barghars. Machhagadh’s barghar Dasuram Tharu says, “This is a new village where freed kamaiyas (bonded laborers) were resettled. None of their finances are stable. Once you become a barghar, you get busy with social work. Instead, if you work as a daily wage laborer, at least you make enough money to feed your family. That’s why it’s difficult to find people willing to take responsibility of being a barghar here.”

Laxmanpur village, which adjoins the Bansgadhi bazaar, sells dhikri (steamed rice cakes) at gatherings and ceremonies. They also rent out a football field and have constructed a picnic spot with a pond. “Others should learn from Laxmanpur village,” says the village’s assistant barghar Ekraj Chaudhary. “New income sources need to be pursued to make the village prosperous.”

Like in other communities, the head of the household in the Tharu community is also usually male. So it is unlikely that head of the village would be a woman. But women have been taking up responsibility as barghars in the absence of men. Somati Tharu has been the barghar for Bathwatal village in Bansgadhi-6 for the past two decades now.

“No one wants to be a barghar,” said Somati. “They find it tedious to lead pujas and continue traditions.” Bathwatal, which has 450 households, does not have a watchman. So Somati, who is not too familiar with mobile phones, travels on her bicycle from neighborhood to neighborhood herself whenever she needs to report something to the village.

In Bethani village, Bansgadhi-2, the dharma bhakari practice has now been transformed into a cash system. According to Bethani’s barghar Hosu Tharu, dharma bhakari has been in practice since the Rana era. Dharma bhakari is a tradition where landlords, under the leadership of the baghar, set aside a certain amount of grain for times of difficulty. Those who don’t have enough to eat take some of the grain and the next year, replenish the grains they had taken with no interest.

Since 1997-98, Bethani’s barghar has transformed dharma bhikari into cash. By December 2023, the fund had accumulated Rs 1.3 million. “We haven’t abandoned our dharma (faith),” says Hosu Tharu. “But we don’t know when the village will abandon its dharma.”

The Thakurbaba Cultural Academy had organized a seminar on around the preservation of Tharu language, art and culture in Bhurigaon on Baisakh 13. Bina Bhattarai, deputy mayor of Thakurbaba municipality, said at the conference, “We people’s representatives are responsible for development. Tol Development Committees have been formed. However, nothing can be accomplished in the Tharuhat without the help of the barghar network.”

The barghar system is not only important for the preservation of Tharu culture and tradition, but also for the collective development of rural settlements. But perverse party politics have also entered the barghar race.

Sita Choudhary of Jonapur village, Godavari Rural Municipality, Kailali was chosen as a barghar through an election. Since Sita was a member of the Nepali Congress, UML supporters in the village refused to accept her candidacy, instead putting forward Bhagiram Chaudhary. Sita won the election by a single vote.

Madhav Choudhary, outgoing president of Kailali’s Tharu Welfare Council and resident of the nearby village of Fakalpur, says, “The entrance of party politics in the barghar system signals a decline of the Tharu village. Villagers did not like it when Sita took the side of the Congress party in some disputes. Therefore, this year, Ramlal Choudhary, who is impartial, has been chosen as the barghar.”

The Barghar Act: populism at the local level?

Barbardiya Municipality, which was first to introduce the Barghar Act, claims that the Act was introduced with good intentions by former mayor Durga Tharu. According to him, the intention was to better organize the barghar system better organized and strengthen both the practice and society. However, it appears that similar acts are now being introduced as a populist measure.

Following Barbardiya’s example, local level units in other Tharu-dominated areas are also promulgating Barghar laws. However, no one seems to have looked into why the Barghar Act has not been properly implemented in Barbardiya.

In Barbardiya’s law, one must have been living permanently in the village for at least five years before they are eligible to become a barghar. In the Barghar Act passed by Dang’s Lamhi Municipality, this period is 10 years.

According to social activist Shekhar Dahit, both Barghar Acts are flawed. He says, “This provision allows non-Tharus who have been living in the respective villages for 5 to 10 years to become barghars.” It is not ideal for non-Tharus to become barghar leaders, says Dahit. A non-Tharu barghar might not affect the social life of the village but it will affect the culture and traditions of the Tharus and will also take leadership roles away from a historically marginalized community.

Barbardiya Municipality’s mayor Chhabilal Chaudhary says that a non-Tharu barghar will not be acceptable since a non-Tharu will not be able to establish places of worship and lead traditional prayers.

Ekraj Chaudhary, who has been helping the local level in the Tharuhat area promulgate similar Barghar Acts, suggests amendments if there are difficulties in implementation. “If the constitution itself can be amended, there’s no reason why an Act promulgated by the local level cannot be amended,” he says. “What’s happening is that such Acts are being promulgated to become popular but there’s no real interest in implementing them.”

Mayor Jograj Chaudhary of Lamahi Municipality, Dang, addressing an interaction event on the municipality’s Barghar Act.

According to Ekraj, when asked about implementation of the Act, Ganesh Chaudhary, chair of Janaki Rural Municipality in Kailali, said that his job was getting the Act passed and that implementation was the responsibility of other officials.

The barghar are there to assist the local level. But it is necessary to improve the promulgated Act if this assistance is to be strengthened and broadened.

We are not asking the municipality for a salary. But we need meaningful participation. We want to preserve our culture but if we are not provided with proper clothes and instruments, we won’t feel the presence of the local government. – Kaliram Chaudhary, President, Barbardiya Municipal Barghar Network

“The ward chair should carry out development works,” says Bam Bahadur Tharu, barghar of Fachkahawa village in Barbardiya-11. “We will limit ourselves to irrigating the fields and carrying out religious work. But the ward should look towards managing our religious work. If the ward could formally honor the barghars during events like Maghi, that would be enough for us.”

Barbardiya Municipal Barghar Network President Kaliram Chaudhary, who is also a member of Tharu Welfare Council District Committee, says, “We are not asking the municipality for a salary. But we need meaningful participation. We want to preserve our culture but if we are not provided with proper clothes and instruments, we won’t feel the presence of the local government.”

Currently, in many Tharu villages, the role of the barghar is now limited to the cultural sphere – performing prayers and dances and managing feasts and wedding parties. There is a danger that the Tharu community will lose its rich traditions of mutual cooperation and self-governance and become more dependent.

“They’ve started asking for allowances even to go to meetings in their own village,” says Niranjan Chaudhary, former ward chair of Barbardiya-10. “Just as some of Nepal’s social institutions were destroyed by ‘NGO-ization’, this Barghar Act too will place traditional institutions into even more of a trap.”