The worsening conflict regarding the use of natural resources between national parks and local units adjoining it has started to affect wildlife conservation.

Mukesh Pokharel | CIJ, Nepal

For the last couple of years, the eighth and ninth wards of Makwanpur’s Manhari Rural Municipality have been disbursing budget to stop encroachment of land by Rapti River in Jyamire’s top but the work is yet to begin. In the fiscal year 2078/ 79, a total of Rs 1.2 million was disbursed for embankment construction. According to an agreement reached on Poush 28, 2078 BS, the consumer committee should complete work by Chaitra 28.

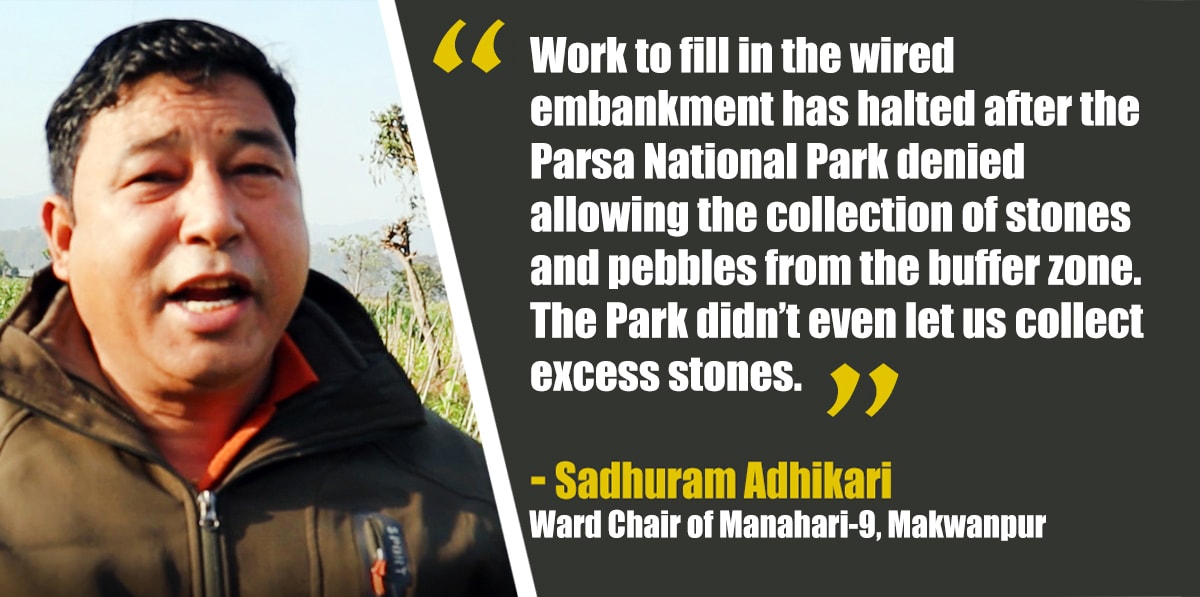

But Parsa National Park has not given permission to collect stones and pebbles needed to fill the embankment from the buffer zone and that is the reason why the work hasn’t begun, according to Sadhuram Adhikari, chair of ward 9.

Bir Bahadur Rumba, chair of the consumers’ committee, says, “We requested the national park office repeatedly. The chief warded has recommended the Lamitar Post to inspect the field condition, but the Post has not taken a step.”

The road from Jyamire to Audhogikdham, the cremation home encroached by the flooding Rapti, and embankment readied by locals of ward 8 and 9 in Jyamire on the banks of Rapti river. Photos: Mukesh Pokharel

Ward chair Adhikari says that if an embankment is not constructed in Jyamire’s top the flood comes monsoon would affect about 3000 households. “The park even denied our request to remove excess stones,” Adhikari laments.

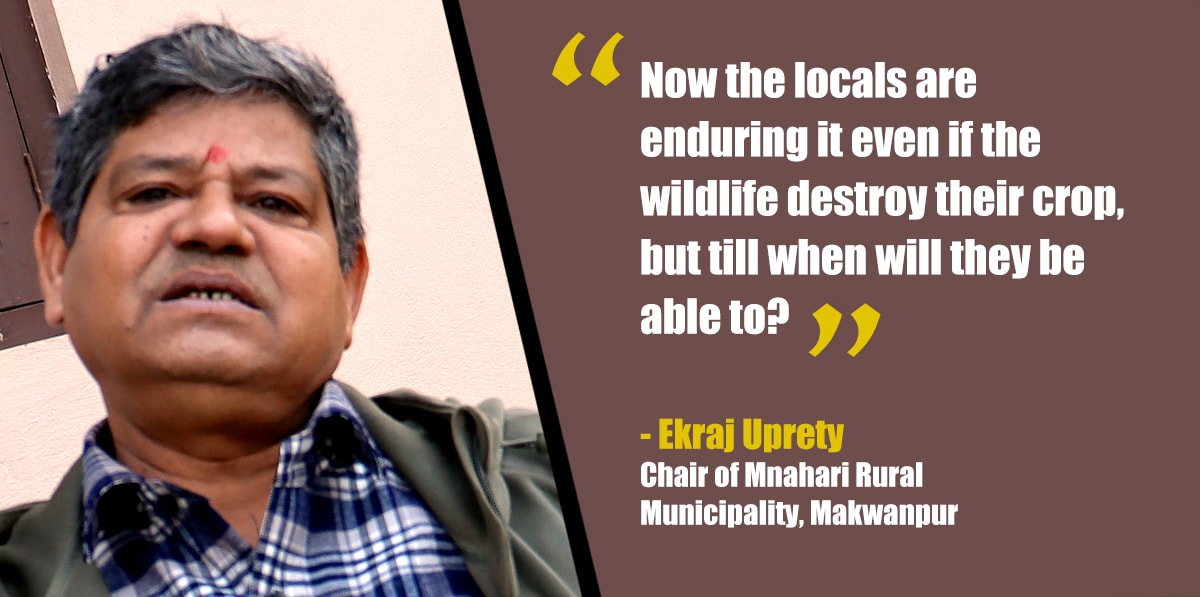

Manahari is a rural municipality that shares a border with Parsa National Park. Ek Raj Upreti, chair of the rural municipality, says that more than half of the park falls at the park’s buffer zone and that’s why there have been hurdles to use natural resources.

The construction of five bridges inside the rural municipality that have already been contracted has stopped. Contracts worth about Rs 53 crores have been endorsed to construct bridges over Tangrakhola, Masinekhola, Haadikhola, Thadokhola and Chyabalkhola. But the work hasn’t moved ahead after the park denied permission to scoop sand and pebbles from the river. Uprety, the rural municipality chair, says that it would require only about Rs six crore to blacktop two km road, cement five km stretch and gravel another 50km, the work has stopped because of the park’s denial.

Peaking conflict

But the conflict between the national park and the Rural Municipality is not limited to only this. Let’s look at other examples of the conflict between the two entities.

Last Kartik, a group of over 400 people, shovels and spades in hand, picketed the Rural Municipality office to express grievance against the national park’s refusal to grant permission to collect sand and pebbles. Uprety, the rural municipality chair, led the group to the Lamitar Check Post of Parsa National Park office.

“The people came with shovels and spades to picket the local unit office, and I told them that it was not we who had denied permission,” says Uprety. “After my failed attempts at convincing, I went myself with the group to picket the check post.”

A similar incident had taken place before this, on Chaitra 2076. The rural municipality did an Intermediate Environment Examination (IEE) with a provision to allow extraction of 260000 cubic meter riverbed material from Manahari and Rapti rivers, and took permission from the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Reserve. But the Park Office put a ban on extraction, which it allowed formerly.

Citing the ban, the team led by Rural Municipality Chief Uprety went to picket the park’s post. A colonel of the Nepal Army who was deployed at the park then asked the agitators to back down, saying that they need to “operate according to the administrative order”. Uprety says, “The next I handed over an ultimatum of next day and returned. And by the evening, the Ministry of Forest decided to allow to resume work.”

Uprety says that his four-year tenure has been spent fighting with the park. “I am now known to all officials at the park, department and the ministry,” he says.

Gopi Lal Moktan, chair of Manahari Rural Municipality-6, says that while the park has received a royalty for riverbed materials, it has not allowed extraction to construct roads in the ward. According to him, Rs 10 lakh has been allocated to gravel the ward’s Pratappur road section but the work has been stopped owing to the restriction in extraction. “Not only that, the embankment project in ward 6 is also halted. The park doesn’t allow extraction of anything from the river,” says Moktan.

Chief Conservation Officer of Parsa National Park Manoj Sah, however, says that there is no legal provision to allow extraction of riverbed material for big construction and crusher industries. He says, “We are ready to address the concerns of small-scale industries.”

Sah alleges that there was a restriction in the monitoring of the extraction allowed to consumers and the material is being sold to crusher industries.

Rural Municipality Chair Uprety, however, rebuffs that allegation. “We haven’t allowed anyone to step on the river at all. Instead, there might have been theft,” he says.

Similar case elsewhere

Like Makwanpur’s Manahari, which lies in the buffer zone, Rasuwa’s Kalika Rural Municipality has also faced the same problem.

Bhawani Prasad Neupane, deputy chair of Kalika, says that pebbles and stones needed for developmental construction have been imported from the Nuwakot district at double the price. “We are compelled to import the material that flows from here in double the price,” he says. “The park doesn’t even allow us to extract the excess material accumulated in the river.”

Kalika Rural Municipality lies in Langtang National Park’s buffer zone. That’s why, the local unit is barred from carrying out development construction, complains Neupane. According to him, the Village Assembly decided to construct a park and picnic spot at Syaubari in Ward 2 during the fiscal year 2074/ 75. According to this, the federal government disbursed Rs 1 crore 19 lakh for the local unit. But the local unit was compelled to return back the budget after the park banned construction citing the location falls in the buffer zone.

Likewise, in the last fiscal year, the Assembly recommended the Land Commission to manage relocation spots for squatter settlements in Kalikasthan. But when the work to level the ground began, the park intervened, says Neupane, adding, “Because the rural municipality falls in the buffer zone, we are deprived of development.”

Meanwhile, Chitwan’s Madi Municipality, which also falls in the buffer zone, decided in its Shrawan 14, 2077 all-party meeting to extract the municipality from the buffer zone.

Mayor Thakur Dhakal of Madi says that problems have incurred for infrastructural development because the local unit has to take permission for each such work. “There’s a lot of stones and sand here but the locals and municipality can’t use it easily,” he says.

Mayor Ghanashyam Shrestha of Bardiya’s Thakurbaba Municipality too says that there has been resistance from the park. According to him, the municipality’s ward 2 has a ground where a stick dance game takes place. Lumbini Provincial government had allocated Rs 70 lakh for the construction of a parapet and managing the ground. But Mayor Shrestha says, just while the construction was beginning through the consumers’ committee, the park administration imposed a ban.

Likewise, while Rs 2 crore has been allocated for a Tharu Cultural Museum in ward 9, the work is halted because of the park’s resistance, says Shrestha.

A President Running Shield tournament has already taken place in ward 1’s Shnghabahini playground. The provincial government has allocated Rs 10 lakh for the management and fencing of the ground but it too met the park’s resistance, says ward chair Shyamlal Tharu.

Bishnu Prasad Shrestha, chief conservation officer at Bardiya National Park, says that local units don’t have to take the park’s permission for infrastructure development in residential areas but they do when it comes to unregistered land or forest area. “Infrastructure development in public areas need to follow environment conservation laws. IEE and EIA process should be carried through,” says Shrestha.

But local-level representatives complain that park administration has tortured them during the process of EIA itself. “They even stop the process of IEE and EIA,” says Mayor Shrestha.

Chief Conservation Officer Bishnu Prasad Shrestha, however, says that the problem arose because the local unit started EIA only after signing the project contract. “Permission should be taken before signing the contract. We can’t allow projects that run even before taking the permission.”

Difference in understanding

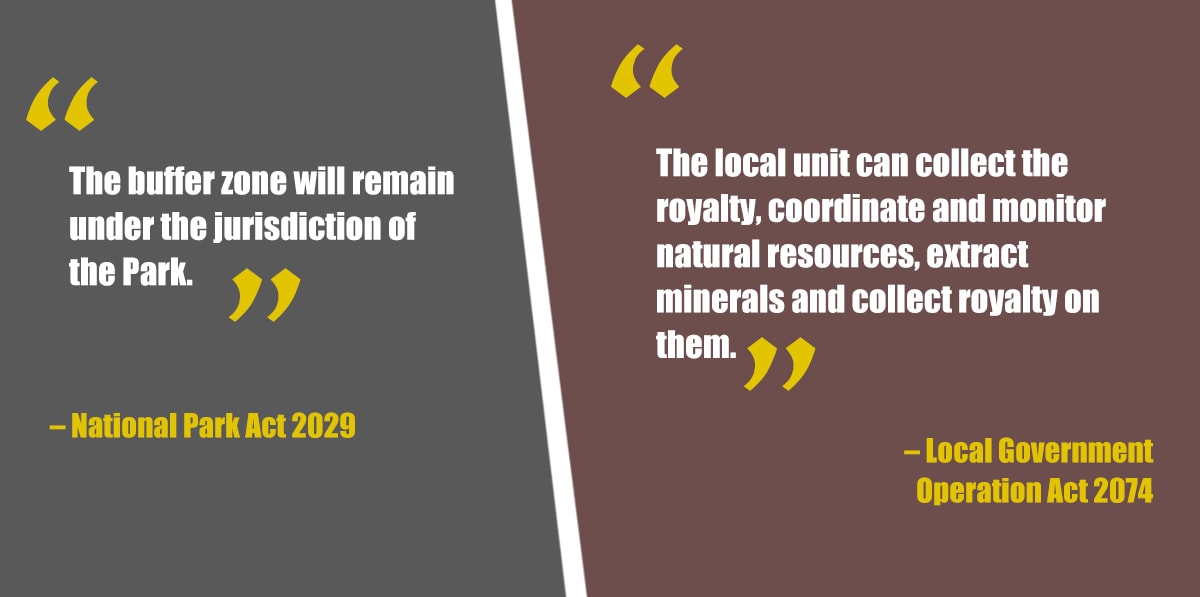

The main conflict between the local unit in the buffer zone and national park seems to be on the right of area. Its main reason is the difference in Local Unit Operation Act 2074 and National Park and Wildlife Reserve Act 2029.

The National Park and Wildlife Reserve Act 2029 deems illegal activities carried out without taking written permission such as controlling land inside the buffer zone and deforestation, extraction of resource and minerals causing harm to the environment, poisoning rivers, streams and sources of water inside the buffer zone, and poaching and harming the animals.

Meanwhile, the Local Unit Operation Act 2074 has granted the right of management of community and religious forest, management of afforestation in roadside, river management, surveying, extraction and use of pebbles, stones, sand, salt, mud, limestone and slate, their registration, permission, renewal, cancellation and management, among other things, to the local unit.

Likewise, the 2074 Act also states that the right of royalty collection of natural resources, coordination and monitoring, extracting minerals and their royalty collection is granted to the local unit.

Because of this provision, local representatives are of the belief that the local unit has the right to land outside the core national park area. But the National Park Act 2029’s provision regarding buffer zone places the zone within the remit of the park.

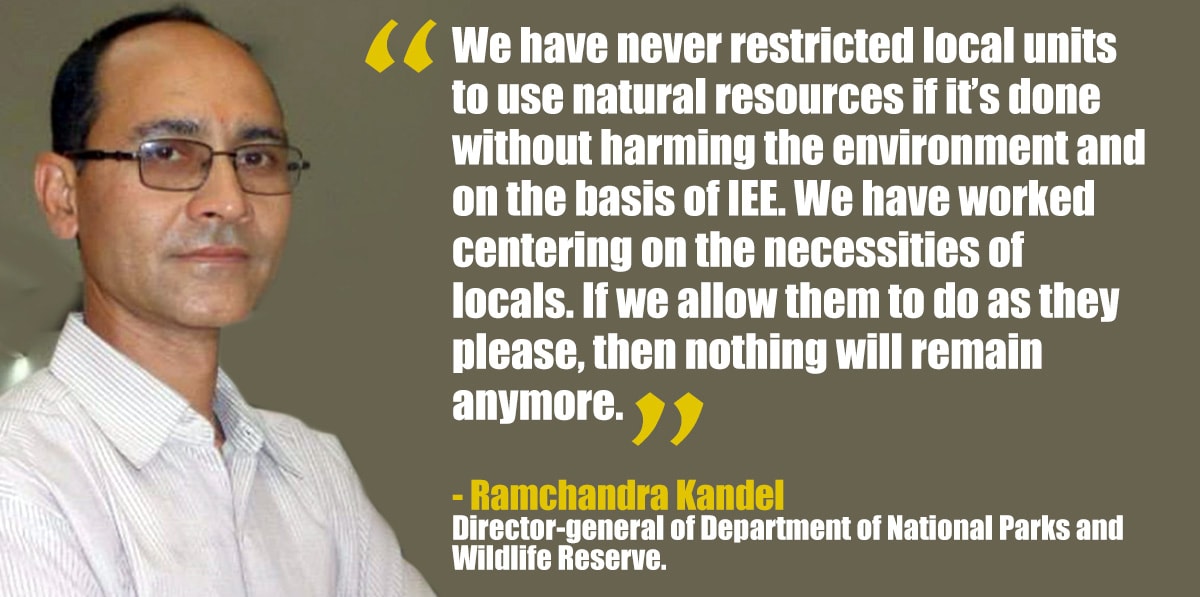

Ramchandra Kandel, general director at the Department of National Park and Wildlife Reserve Conservation, says that the park hasn’t gone outside the remit of the legally granted right.

Kandel, who claims that the department has never obstructed local units from use of the natural resource on the basis of IEE and without harming the environment, says, “We have worked focusing on local necessities. If we allow them to do as they please, it will create havoc.”

Santosh Mani Nepal, who is also an expert member of the parliament’s natural resource committee, even though concern regarding granting the right of the buffer zone to the local unit was raised during the constitution drafting process, it is under the jurisdiction of the federal government. “Buffer zone falls under the remit of the federal government,” he says. “It is imperative we move forward clearing out the confusion regarding resource use.”

In some places, there might have arisen some problems because of a lack of coordination. “But not all places have the same kind of problems,” he says, “it is easier if a methodology is drafted to solve the problem related to a specific place.”

The government on Jestha 29, 2077 had formed a high-level committee to investigate the trafficking and cutting down of valuable trees such as saal.

That committee had submitted its report to the government on 2077 Bhadra after researching it. The five-piece committee, led by Dr Netra Prasad Timilsena, had concluded that conflict was on the rise between the conserved area, buffer zone and local unit.

The report states that the feud had given rise to human-wildlife conflict, the local units were curtailed of their right to carry out infrastructure development in the local unit freely and rise in the feud about the use of natural resources in the buffer zone.

According to the committee’s recommendation to the government, infrastructure development carried out by local units inside the buffer zone or conservation area should be done consulting conservationists in case of public land and in case of private land, local units can decide the use of riverbed material and minerals on the basis of EIA, and designating a certain quota.

Chiefs of local units, however, say the law should be amended in a timely manner. Thakur Dhakal, mayor of Madi, says that the law promulgated in 2029 is not relevant anymore and hence should be amended. “The current problem can’t be solved without amending the Act,” he says, “Since the adoption of federalism, it makes sense to conclude the allocation of rights by amending the law.”

Challenges in conservation

The concept of the buffer zone started in 2052 BS after concluding that conservation is not possible without the participation of locals. But given the rise in conflict regarding natural resource use between the government and park administration, it appears more challenges would accumulate in the future. In fact, the death of wildlife outside the park strengthens this conclusion.

An adult tiger was found dead in Daunnedevi Community Forest in Nawalparasi on Magh 15, 2078. Locals had discovered the dead tiger while vising the forest to fetch grass.

Once the death of rhinos increased in Chitwan, the Ministry of Forestry and Environment had formed a working committee in 2076. The committee found out that of the 18 dead rhinos, four had succumbed after ingesting poison. The committee suspected that locals might have poisoned the rhinos after the tuskers destroyed crops.

Shivaraj Bhatta, the conservation director of WWF who is also a member of the committee, says that the locals are prone to killing the wildlife out of anger.

“If the locals don’t feel the need to conserve the wildlife, then it poses an extra challenge,” he says. “Incidents where wildlife outside the park are poisoned or electrocuted to death can increase. Therefore, if there’s any problem, it should be settled through mutual discussion.”

Uprety, the chief of Manahari, too doesn’t rule out this possibility. If locals don’t identify with the wildlife and face problems from them, then it would add an extra challenge, says Uprety. “Currently, locals are bearing with the fact that wildlife occasionally destroys their crops,” he says. “But if they can’t develop their area, till when will they endure it?”