Nepal’s cabinet secretly ratified National Security Policy which has identified foreign intervention, open international border, border encroachment, infiltration and fuel/energy crisis as key security challenges.

SAROJ RAJ ADHIKARI– Centre for Investigative Journalism

The National Security Policy 2016, recently ratified by the cabinet, lists foreign intervention, open international border, border encroachment, infiltration and fuel/ energy crisis as major security challenges for the country. Similarly, transition into new governance system, political instability and polarisation, entrenched communalism and regionalism have been mentioned as internal security threat.

The document further lists politicisation of crime and criminalisation of politics, white-collar crime, increased violence at community level, weak economy and dependency, separatist groups and their activities, as well as strategic interests of regional and global powers as security challenges, and outlines various strategies to address these challenges.

‘National Security Policy is an umbrella-policy that guides other policies including those on public security, and is therefore a public document. However, strategies and operation modalities made by security bodies under this policy may be classified’

‘National Security Policy is an umbrella-policy that guides other policies including those on public security, and is therefore a public document. However, strategies and operation modalities made by security bodies under this policy may be classified’

‘National sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country shall not become a subject of discussion and compromise, and all forms of extremist and separatist tendencies will be discouraged’, the working policy section of the document states.

Taking que from the shortages of goods and fuel during the recent Indian blockade, the document points at the need for, ‘establishing a well defined criteria for storing essential goods including foodstuff, fuel and medicine, and a secure distribution system that is also efficient.’

The document stresses on improving and strengthening counter-intelligence capacity of national intelligence agency. The country’s only counter-intelligence body was disbanded in 1992, and beyond occasional talks of reviving the body, nothing much has been done. A former home minister reckons, this is due to disapproval from southern neighbour India.

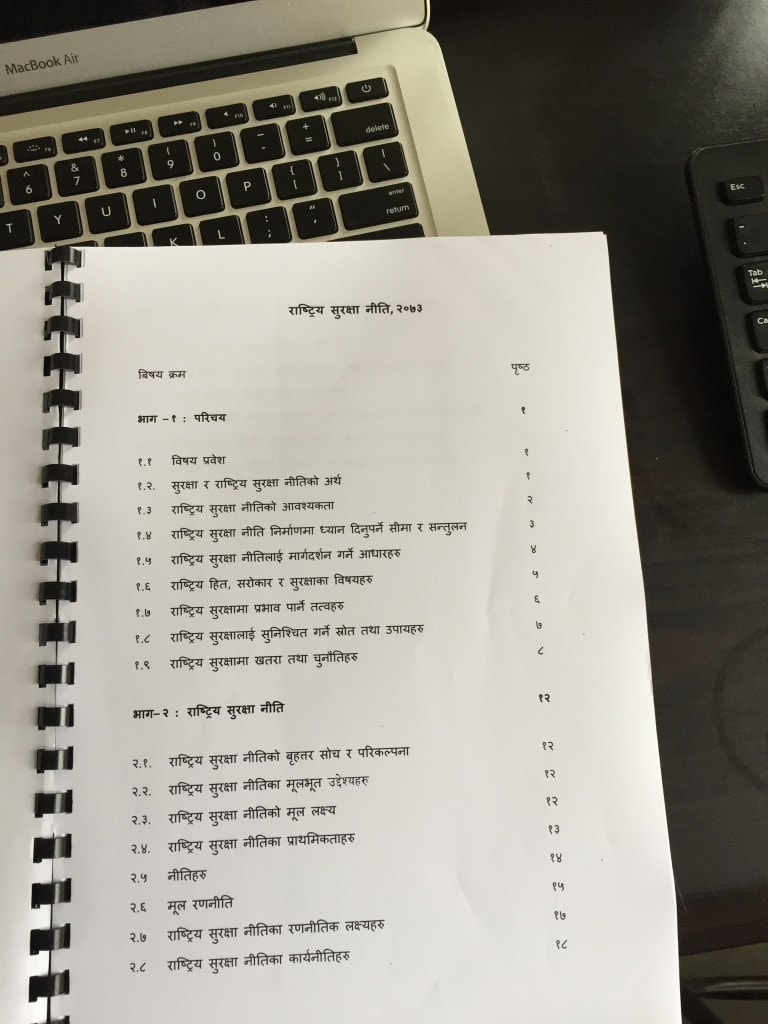

National Security Policy 2016

The policy also calls for monitoring, regulating and controlling activities of I/NGO in the country. According to the document, this will be done by the intelligence agency.

When the national security policy was being drafted in 2009, I/NGOs had overstepped their working jurisdiction and organized public debates and discussion on the issue.

The national security policy also prevents Nepal Army and other security bodies from holding casual visits with security counterparts stationed at various foreign missions within the country. The document states, ‘countries that have bilateral ties with Nepal shall coordinate security-related activities and interactions through Nepal government’s Ministry of Defence.’ Until recently, the Chief of Army Staff, heads of other security bodies, and high ranking officials had been meeting and visiting security counterparts of other countries without any restrictions.

The policy also includes possibility of introducing conscription into military service for citizens of a particular age group, so that they can be mobilized into state services should the necessity arise. The Maoists had been lobbying for a mandatory conscription for all citizens, and had protested when the provision was removed from a policy draft in 2010. The document could not be ratified back then.

‘It is a public document’

The document passed by the National Security Council on 6 May and ratified by the cabinet on 11 May has yet to be made public. According to a source, the document had been marked ‘Secret’ and made available only to selected cabinet ministers and top bureaucrats.

But, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Kamal Thapa insists, the document is not confidential. ‘The government will make the document available to individuals and organisations who are deemed important, if they fulfil proper procedure’, says Thapa, adding that the policy has been in effect since the day it was passed.

But, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Kamal Thapa insists, the document is not confidential. ‘The government will make the document available to individuals and organisations who are deemed important, if they fulfil proper procedure’, says Thapa, adding that the policy has been in effect since the day it was passed.

Nabin Ghimire, former Secretary at the Defence and Home ministries, who prepared the initial draft of the policy says, security policies of more than 25 countries were researched and Nepal’s unique problems, priorities, necessities were considered while preparing the initial draft.

‘National Security Policy is an umbrella-policy that guides other policies including those on public security, and is therefore a public document. However, strategies and operation modalities made by security bodies under this policy may be classified’, says Ghimire who is now a commissioner at CIAA.

Former Nepal Army General, Balananda Sharma agrees with Ghimire and says, a document made in public interest cannot remain confidential.

‘The office of the US President amends National Security Policy every two years and makes it public. The public has the right to know policies that guide their security.’ says Sharma, who headed Maoist Combatants’ Integration Special Committee Secretariat.

The fact that, one months since its ratification by the cabinet the document has not reached Nepal Police which is entrusted with domestic security, raises concerns around its secrecy.

‘ I have yet to see it.’, confirms IG of Nepal Police Upendra Kanta Aryal.

NC central committee member Gagan Thapa, who heads parliament’s Agriculture and Water Resources Committee, said he was denied access to the document despite fulfilling due procedure.

‘Ten days back, i sent them a request for a copy for research purposes on behalf of the committee. But, Chief Secretary Somlal Subedi told us they were not authorized to give us a copy.’ said Thapa.

Thapa suspects the government has deliberately denied members of his party from accessing the document. ‘Agriculture and water resources are issues of national security interest, and fall under working aegis of the committee. It is bad enough, they bypassed us while formulating the policy. Now, they are denying us access to the document that has already been ratified by the cabinet.’

‘Agriculture and water resources are issues of national security interest, and fall under working aegis of the committee. It is bad enough, they bypassed us while formulating the policy. Now, they are denying us access to the document.’

-Gagan Thapa, Chairman of Parliment's Agriculture and Water Resource committee

But Gen. Sharma believes sensitive issues like national security should not become a matter of petty politics. ‘Since both the governing and opposition parties need to be on the same page when it comes to key national security interests, the policy should have been drafted after holding consultations and gaining confidence of all stakeholders inside and outside the parliament.’ said Sharma.

Ghimire recalls how the 2010 draft could not be passed due to difference within the parliamentary committee, and suspects the current draft must have been passed without any discussion to prevent further bickering.

‘I think they should have had made it public and held discussions, even after ratifying it. The resulting feedback could be really constructive and helpful in making amendments,’ says Ghimire.

Mahesh Prasad Dahal, secretary at the Defence Ministry, defends the government and says, ‘the document has not been made public yet because we are still preparing to publish it.’

This is the first time in Nepal’s history, such a comprehensive national security policy was drafted. After the unification of Nepal in the mid 18th century, Prithvi Narayan Shah’s ‘Dibya Upadesh’ was adopted as a security policy. Later, security experts interpreted the National Policy (Red Book) 1985 as a security policy document. Although it partly addressed public security, the Red Book’s main object was to defend the partyless Panchayat system, and it contained longer lists of duties than citizen’s rights. It did not fulfill requirements of a national security policy.

The National Security Council, after its establishment in 2002 began its homework for drafting a national security policy. But the process did not gain momentum. Similarly, in 2010, Nepal Army also submitted a document titled ‘Central National Policy and National Security Policy 2010,’ as envisoned by the Nepal Army’ to the government.

A cabinet meeting on 24 December 2009 had also established a committee headed by then Defence Minister Bidya Bhandari to prepare a national security policy and a mechanism to democratise Nepal Army. Secretary at Defence Ministry, Nabin Ghimire was a member of the committee that prepared initial drafts in 2010.

The State Management Committee of the Constituent Assembly tabled both documents for discussion. However, the main opposition UCPN-M protested, citing that the document does not address their concern. Some smaller parties also voiced their disagreement.

Today, the Maoists are a chief ally of governing UML coalition, and it is to address their concern, word ‘illegal’ has been added in front of the phrase ‘armed activities and struggle’ mentioned in the 2010 draft. It is ironic that the word should be added, since Nepal’s domestic laws already define ‘armed activities and struggle’ as illegal. The document was prepared and ratified under the leadership of DPM and Defence Minister Bhim Rawal.

Every country prepares national security policy according to its own concern and priorities. For India, China and Pakistan, border issues, terrorist activities, and military competition are a priority issues. For the USA, global terrorism control and expansion of military capacity is a priority. For Maldives, it is climate change and environmental security. For many African countries, whose natural resources and minerals are under the control of powerful countries, preserving national interest is a priority.

Traditionally, national security was viewed through a narrow military lens. But, in the changed context, such a document keeps security of citizens, rather than territory at the centre.

A sound national security policy document should address dimensions of politics, economy, social security, natural resources, diplomacy, environment, energy, culture, information technology, public and private value systems, climate change, natural disasters, property, national pride, and human rights.

‘The main objective of a national security policy is to free the public from fear and want.’, says Ghimire. ‘Security bodies can address the fear, but in order to free the public from shortages, all state bodies need to make a uniform effort.’