While queer Nepalis have been facing social ostracization and violence for long, the Dalits among them face even worse.

Lokendra Bishwakarma | CIJ Nepal

The Basantapur village lies about 18 kilometres west from Ghantaghar in Birgunj. In late April, the temperature in the village exceeded 40 degrees centigrade. But for Chadani Yadav, the heat was not much of a concern, for she had a more pressing problem at hand—the pain of discrimination and violence.

“We are more perturbed by the pain of violence and rape than the heat,” Chadani said.

At about 11 pm on April 21, Chadani was preparing to sleep when she heard a knock on the door. There were three middle-aged men.

“Who are you, why are you here?” Chadani asked.

“We’re here to have fun,” one of the men replied.

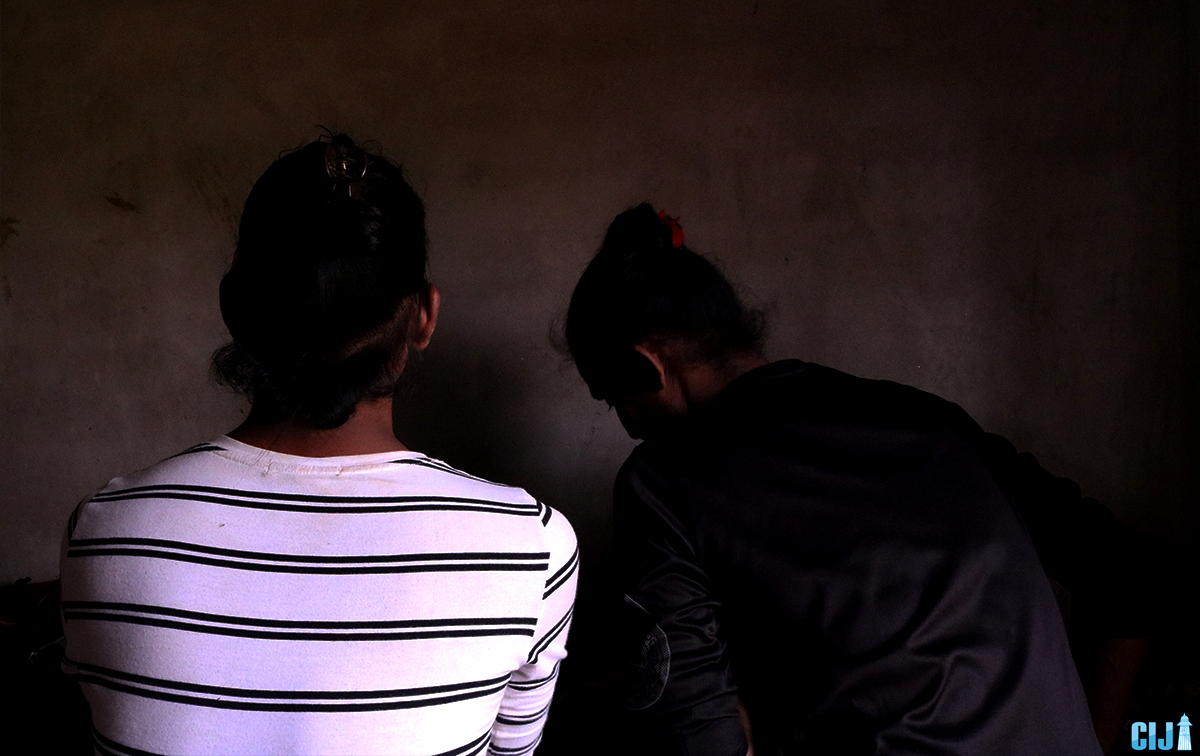

Scared, Chadani attempted to lock the door but the men stopped her and barged into the room. They then raped Chadani, Naina and Muskan.

“All the three men came to our beds and forced themselves upon us,” Chadani said.

Incidents of violence like this against Chadani, Naina and Muskan, all of whom are nonbinary individuals, are routine. And they have nowhere to turn to for justice. “We can’t do anything even if we want to,” Chadani said. “If we file a complaint, we receive the blame instead.”

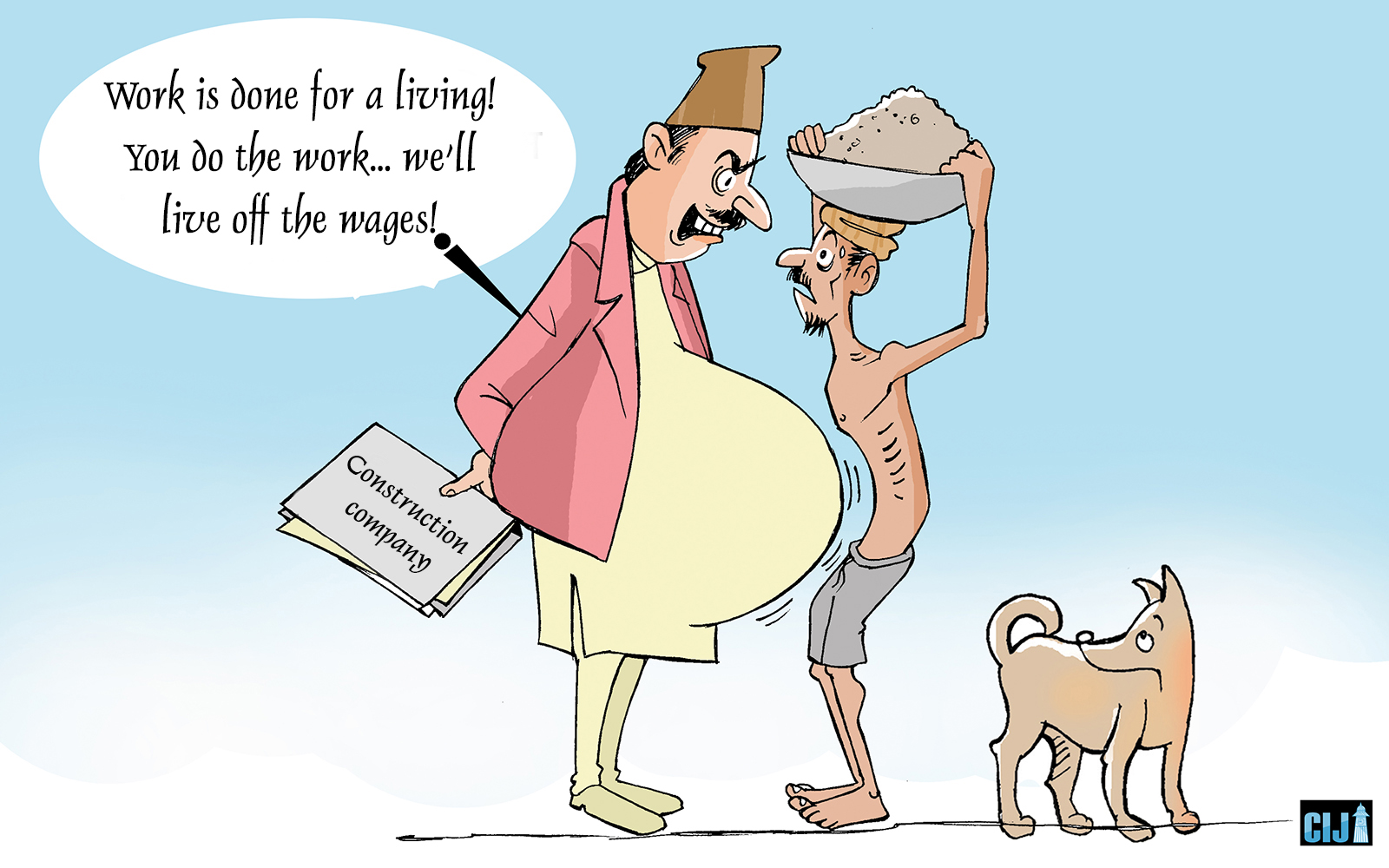

Though Chadani says her surname is Yadav, she actually belongs to the Madhesi Dalit Mahara community. After she struggled to make a living, she changed her surname and began to work as a dancer at weddings and dancer bars. “We have to change our surname to get work,” she says.

Chadani was born a male. It was only five years ago that she came out. Then she had to face abuse from her family and the society. She had to move to Janakpur from Mahottari. “They began to call me names like chhakka, hijra and mauga [derogatory terms used to refer to nonbinary individuals] and forced me out of the village,” she said.

Chadani, who has studied up to grade 12, didn’t get a job in Janakpur either. While some hoteliers were ready to give her a job despite knowing she was identified as nonbinary, they fired her upon knowing that she was also a Dalit. She had to face more caste discrimination in the city than in her village.

Then she migrated to Birgunj. She reached Mainapur in Birgunj to dance at a wedding ceremony in Mangsir, 2079. While returning from the ceremony at night, a group of four individuals offered her and her friend a ride to their room. But when she spoke with her friend in Meti language, the colloquial dialect used by nonbinary people, the group knew about her identity, that she was not only a nonbinary but also a Dalit, and then they dropped her and her friend off.

“And what happened after that?”

Upon being asked this question, Chadari began to sob uncontrollably. “The men forced us to go into the jungle calling us hijras, and when we protested, they burned our skins with cigarettes,” Chadani said. “They raped us that night and left us there.”

The next day, when she shared the episode to her landlord, she received this reponse, “Don’t go to such a place from now onwards.”

The landlord is themselves a person from the nonbinary community, who facilitates and manages other LGBTQI persons to work as professional dancers. When the landlord did not help her file a complaint with the police and bring the perpetrators to book, she was dejected. She then left that rental. The violence and dejection kept on following her.

Double discrimination

Like Chadani, 22-year-old Riya Mandal, who is a trans woman from Mahottari, has also faced the horrors of caste discrimination and it has even led her to abandon her studies altogether.

As she was growing up, her teachers and friends would mock her a lot and she dropped out after grade 8. It’s been six years since then.

Because of her voice and gestures, she faced discrimination even at her village. The discrimination grew so intense that she decided to leave her village.

She arrived in Bariyapur of Bara and began to dance at various functions to make a living. She faced countless episodes of discrimination during the period. Her love affair also didn’t last because of her caste. “He is a Dhanuk Mandal and when he knew I was a Dom Mandal, he left me,” she says.

Of the 16 nonbinary Dalit the CIJ talked to, eight have left their villages because of caste discrimination.

According to a 2076 BS study report of the National Human Rights Commission, gender minorities feel neglected by their families and society. Majority of those belonging to minority genders tend to stay away from schools, villages and society, the report says.

The report further says that they face difficulties in staying in their societies. But Dalit nonbinary people tend to face discrimination even within their own communities.

For Nima Sunar, a trans woman from Humla, poverty and untouchability is a part of daily life. A talented student since her childhood, she got an opportunity to study at Sankrit Secondary School in Ranipokhari on a residential scholarship.

She arrived in Kathmandu at the age of 13 with a cousin brother and got enrolled at the school. As a Dalit, facing discrimination at a Sanskrit school was normal for her. “Since I faced so much discrimination, I couldn’t continue studies after grade 12,” Nima said. Until then, she used to identify as a male. “Even those from my own community discriminate against me,” says Nima, who works at a rights organisation now.

When she was at the school, she fell in love with a person beloging to the Upadhyay Brahmin community. She had let her lover know about her gender identity and her partner was a nonbinary individual as well. He used to tell her that he was also a gay, so he loved her. Since both of them respected each other’s identity, their love grew dense.

But gradually, Upadhyay began to detach himself from Nisha. Nisha says that caste was the reason behind that.

“I spent the money that my parents sent by working hard in Humla on him,” Nisha said, tears welling up in her eyes. “But he began to say that since I was a Sunar, he wouldn’t accept me.”

Bipin Nepali from Butwal also shares a similar experience of discrimination. Nepali is a gay man. “I could endure the discrimination I faced due to my gender identity but it was hard for me to get ostracised by my own community due to my caste,” he said.

Dipesh Bayalkoti of Hetauda, who considered themselves as a woman, committed suicide following episodes of discrimination and harrasment. Royal Sunar, who works at the Blue Diamond Society and is knowledgeable about the incident, says, “We learned that their brother frequently gave them physical and mental torture. The villagers discriminated against them based on their caste. So they had chosen to kill themselves.”

According to a research of Samari Utthan Sewa on the mental health of gender minorities of Dalit communities, 85 percent responded that they had suicidal thoughts. Out of the 100 respondents, 10 said that they did not have such thoughts, and 5 did not want to comment on the matter.

Nonbinary Dalit individuals invisible to political parties

According to data from the census of 2078 BS, there are 2,928 people belonging to the ‘other’ gender. Of them, 304 are in Koshi, 729 in Madhesh, 956 in Bagmati, 228 in Gandaki, 432 in Lumbini, 81 in Karnali and 198 in Sudurpaschim province. The census, however, doesn’t categorise them based on caste. According to data from Samari Utthan Sewa, which works for Dalit gender minorities, there are over 500 queer Dalits across the country and of them, those in the Madhesh face the most incidents of violence and discrimination. Researcher Shivaharu Gyawali also agrees to that.

“Queer Dalits have been facing discrimination and violence around the country but those in the Madhesh face it the most,” he says.

But many of them choose to remain silent about the incidents of violence and discrimination due to their economic condition, Gyawali says.

Other researchers find faults in the data about queer Dalits. Sulochana Panchakoti, who is researching about queer Dalits, says that the official data are not wholly trustworthy.

“Many of them hide their identity from their own families and I don’t think they revealed their true identity to census officials,” she says.

Panchakoti adds that the state has been neglecting the plights of queer Dalits.

“The issue of queer Dalits hasn’t gotten space in Dalit rights movement either,” she says. “And the state is completely unaware about their plights.”

The representation of queer Dalits in organisations like Blue Diamond Society and other queer rights groups is nonexistent. That’s another reason the issues of queer Dalits have fallen in the shadows, researchers say. According to a report published by UN Women in June 2023, queer Dalits usually don’t seek support to deal with the violence that they endure as they hesitate to share it with anyone. Lack of their representation in queer rights organisations is one reason behind that, the report hints. Another is the fear of further discrimination.

The report points out the need for effective intervention from police makers and service providers to address the challenges faced by queer individuals due to their socio-economic status, disability and caste.

Nepal’s constitution has ensured the rights of individuals against untouchability and discrimination. The Caste-based Discrimination and Untouchability (Crime and Punishment) Act 2011 has defined caste-based discrimination and untouchability as a criminal offence.

The Act has also categorised discrimination on the basis of tradition, ritual, religion, culture, caste, community and profession, among others, as a criminal offence.

Bimala Gayak, a rights activist, says that the state hasn’t taken the violence and discrimination against queer Dalits seriously. “Political parties enmeshed in ‘vote politics’ never prioritised this issue,” she says.

Like for various classes, geographical areas and communities, the constitution has also mandated the representation of gender and sexual minorities in various state agencies.

According to data from the Election Commission, there was not a single candidate representing the queer community contesting for a Parliament seat in the election of 2022. Meanwhile, there was only a single candidate vying for a position at provincial assembly, contesting from Sarlahi for Madhesh provincial assembly.

According to the commission, there were as many as 51 Dalits in the first Constituent Assembly of 2008. The number went down to 41 in the second Constituent Assembly of 2013. The number went further down to 20 in the House of Representatives in 2017 and then to 16 in 2022.

Activist Gayak says, “Queer Dalits won’t get rid of brutal treatment until the laws are properly implemented, until there is widespread awareness, and until they are represented in state agencies.”