Political parties, supposed to follow rule of law, are abusing the law to punish representatives at the local levels for ‘quitting the party’.

Krishna Gyawali |CIJ, Nepal

Mahadev Singh Dadal, a Nepali Congress politician, is ward chair of Darchula’s Marma Rural Municipality-6. Soon after he was elected, the district chair of Nepali Congress, Lalit Singh Bohara, had given him some instructions, according to Dadal. “Whatever you do, do according to what the office help Amar Singh Kotari tells you,” Bohara had told Dadal, the latter claims, adding that he refused to follow the instruction.

In a fit of rage after being denied, Bohara sent a letter to Nepali Congress central office saying that Dadal had quit the party. In its meeting on Mangsir 29, 2076, Dadal was outed from the party. The party also sent a letter to the Election Council asking it to make Dadal’s seat vacant. According to which, he was relieved of his position of chair.

Another example comes from Baglung. On Kartik 12, 2076, officials including ward chair Tilak Pun of Dhorpatan Municipality-4 were physically assaulted. The attack had stemmed from an intra-party feud. Later, they were accused that they had “wasted relief material meant to be distributed for Covid-19 patients.”

It was not easy to sack him on the basis of these allegations. Then the Rastriya Janamorcha party accused him of entering Congress party. Ward chair Pun and ward member Tilak Fagami were alleged of attack and quitting the party and were sacked from their party duties. The election council soon issued a letter saying their positions were now vacant.

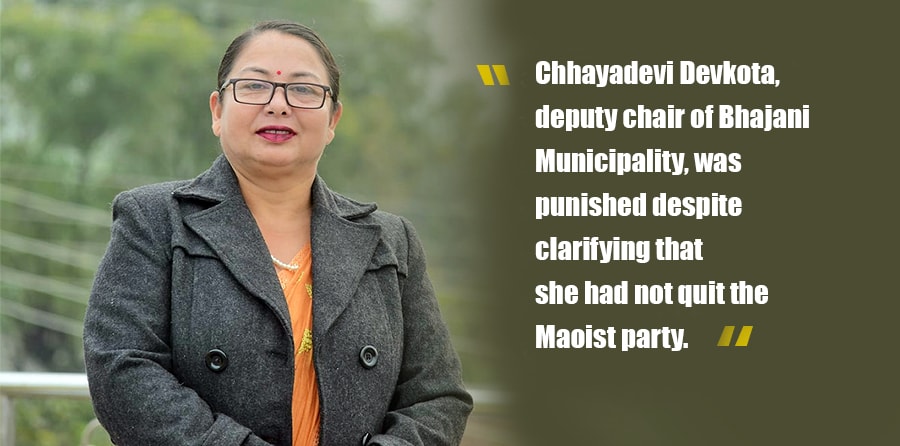

Deputy mayor Chhaya Devi Devkota of Kailali’s Bhajani Municipality was elected under Maoist (Centre) party. After the party merged with CPN (UML) to form CPN, she naturally became its cadre. The parties reverted back to their previous status after a Supreme Court order. After which, she was accused of “entering UML party”, which she denied. But suddenly, on Asar 11, 2078, the election council released a notice on Gorkhapatra that her position was now vacant because she was sacked by her party.

“Quit the party”—a ploy to sack people’s representatives

In all three aforementioned cases, the election council had punished them after their respective parties’ central committees alleging they had quit the party and entered other parties.

According to Chief Election Commissioner Thapaliya, since the first local elections in 2074 BS, various parties had sent letters to sack a total of 32 people’s representatives. Of them, 28 have been punished, according to the election council’s record. But the supreme court has ordered that the punishments be withheld saying that the constitutional provision is different and there are questions regarding the process. The people’s representatives have returned to work.

Why are so many people’s representatives who were elected through their party’s recommendation being punished by those very parties? To know this, let’s take a look at the act relating to political parties. According to the 31st clause of Article 6 in Act about Political Parties 2073, if a person elected for public position through a party’s recommendation quits that party, then their position will be vacant, effective immediately.

For that, any one out of three conditions should be taken into account. First, if the representative submits a written resignation to quit the party; second, if the representative takes membership of another party; or if they establish another party. These conditions are as per the Act’s article 32.

But the major parties are sacking the representatives alleging them of taking membership of other parties, even though they have never resigned form the party. Election Council too never questions whether the parties have done their work according to methodologies. Instead, it seems the council endorses whatever recommendations the parties’ central committees make.

Different constitutional provision

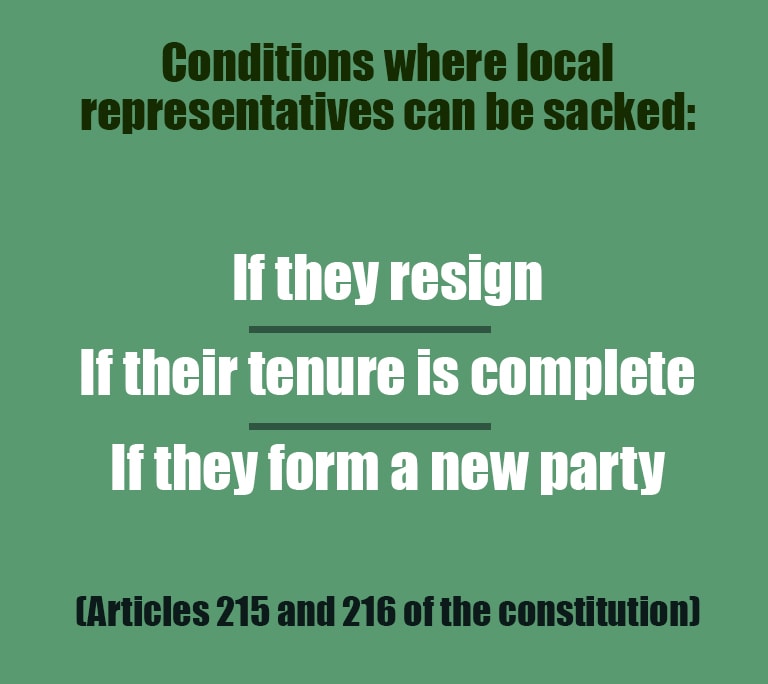

But the constitutional provision is different than this. The Article 215 of Nepal’s constitution has provision about conditions where representatives’ position can be vacant in case of rural municipalities and article 216 in case of municipalities. The eighth subclauses of both the Articles have conditions where positions of local units’ chair, vice chair and members can be vacant. According to which, three reasons are liable for positions going vacant: if the representative resigns, if their tenure ends or if they die. There is no provision related to quitting the party here.

This is how the provision for ‘when one quits the party’, which is not in the constitution, was added on the Act on Political Parties 2073’s Article 31 was added. Dinesh Thapaliya, the chief commissioner, says that even if the provision is on the constitution for federal and provincial members of assembly, it is not fair for local level representatives.

“When one skims through the provision on the act, it might appear natural and fair to sack a local representative if they quit their party,” says Thapaliya, “it doesn’t match with the provision on the constitution. If we are to honor people’s votes, then this provision needs to be amended.”

Thapaliya admits that the commission is compelled to publish notice of vacancy according to the act, not the constitution.

Local representatives were elected to office from the 2074BS’s local level elections. The act related to political parties was passed a year before. Even though some political parties had occasionally decided on provisions for quitting the party at local level, its official use started on 23 Falgun, 2077.

After the Supreme Court ordered that CPN (UML) and CPN (Maoist Centre) would return to their previous status to solve the debate around the registration of Nepal Communist Party, many people’s representatives from the Maoist party began to associate themselves with the UML. And it was after this that the Maoist party started to send letters to the Election Commission to relieve those represntatives of their jobs. Of the total representatives recommended to be sacked, half are from Maoist party.

According to the commission’s data, in the last four years, the punishment against 28 representatives has been halted after the supreme court’s order. Some representatives have returned to work after the high court’s interim order. Thapaliya says that the parties have made recommendation to punish 34 representatives during this period.

For some representatives, however, the commission hasn’t started the punishment process citing faults in the procedure. “In the case of quitting the party, all role is played by the political parties,” says Thapaliya. “The commission’s role in this is only to publish the notice received from the party’s central committee decision.”

Ad hoc decision making

According to the commission’s current practice, it would publish the notice of vacancy once the party’s central committee sends its decision. The commission doesn’t examine whether the decision is based on the Act on Political Party, 2073. But the Act has procedures that the party needs to fulfil before sacking a representative from their party membership. The commission should have only used its right once that procedure is fulfilled.

According to the Act’s clause 32 subclause 3, before sacking a representative from a party, the central committee should provide a chance at clarification. In addition, the act imagines that for that action, the party can form an examination committee. Once the representative in question issues their clarification, the party can decide whether it’s satisfactory or not. The subclause 5 states that if the clarification is not satisfactory, the central committee can sack the representative revealing the action’s basis and reason.

The decision on Chhaya Devi Devkota, deputy mayor of Kailali’s Bhajani Municipality, is an example of this. Even though she clarified that she was still with Maoist Centre and not with the UML, she was punished. “The party can’t punish me based on speculation that I had entered UML and because I had supported KP Oli’s actions while the party was still united,” Devkota’s appeal to the Supreme Court reads. “We haven’t entered KP Oli-led UML, neither have we taken its membership.”

The decision on Chhaya Devi Devkota, deputy mayor of Kailali’s Bhajani Municipality, is an example of this. Even though she clarified that she was still with Maoist Centre and not with the UML, she was punished. “The party can’t punish me based on speculation that I had entered UML and because I had supported KP Oli’s actions while the party was still united,” Devkota’s appeal to the Supreme Court reads. “We haven’t entered KP Oli-led UML, neither have we taken its membership.”

Fourteen local level representatives including Devkota were sacked by the Maoist party. The central committee had handed over the authority to sack representatives to chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal. An official from the commission says that the central committee can’t hand over its authority stated in the act.

A government lawyer at the Office of Attorney General says that the Act related to Political Parties imagined the provision for sacking representative targeting provincial and federal parliamentarians. The clause 32 of the Act states that if a member quits the party, the central committee should receive the information according to clause 28 and the process would begin thereafter.

The clause 28 only has the provision to punish federal and provincial lawmakers if they neglect party whip. The government lawyer says, “If one looks closely at the Act’s provision, it is not possible to punish local level representatives.” Reena Kumari Sah, mayor of Rautahat’s Maulapur Municipality, was punished by the Maoist party as per the clause 28 which is applicable only to federal and provincial parliamentarians. She was then sacked with the chair’s sole decision alleging her of joining the UML.

According to Sah, she has not joined UML. The Maoist party didn’t even think it necessary to collect basic evidence of her joining the UML. So much so that the central committee didn’t even ask her for clarification.

The Maoist party also punished Suresh Kumar Thapa, ward chair of Champadevi Rural Municipality-7 in Okhaldhunga, on similar charge. Despite the fact that he had claimed he was with the party and had not joined the UML.

The two punishments meted out by Rastriya Janamorcha in Baglung’s Burtibang are of similar nature, too. The debate inside the party snowballed to scuffle to physical assault. After the feud climaxed, the party asks for clarification from the people’s representatives.

The Act states that punishment is possible only if the representative in question resigns the party, takes memebership or another party or forms another party. But the Janamorcha party’s questioning for clarification didn’t include these concerns. The party accused the representatives of not promoting their fellow party members’ bid for provincial assembly membership, of voting for Nepali Congress party and encouraging others to do so, not paying levy to the party, and engaging in other parties’ programs.

But these allegations do not concern with the punishment according to the Act. This feud which stemmed from clarification questioning had reached to the Election Commission, which issued notice of vacant position, but is now withheld by the top court’s interim order.

The Commission seems unable to control the punishment of biased nature meted out by the parties, despite the Act’s clear mandate. Even though the commission has questioned recommendations without the central committees’ decision, it has not apparently questioned the subject matter and process of the recommendations.

“It is stated the the commission would vacant the positions only after the recommendation letter fulfils all the process,” says Thapaliya. “But to question whether the party’s decision is fair is not within the commission’s jurisdiction.”

Democratic norms and Supreme Court’s leash

Nepal’s constitution embraces the multiparty democratic system as an unchangeable provision. Candidates contest elections under the party’s banner. But many argue that if a representative joins another party just after getting elected and is not punished, then it would hamper the democratic norms.

Former chief justice Balaram KC worries that if a representative gets elected under a party’s banner, and goes on to change the party once elected, then that would fuel political degeneration in a country like ours. He says, “If a representative is not punished even if they neglect party’s whip and influence voting process, then that would derail the discipline of political parties in a country like ours. That would give rise to opportunism, and it is necessary to control that.”

But if we leave aside a few exceptions, almost all of the representatives punished by the party and the commission have returned to work following the apex court’s interim order. For the first few cases, the court issued an interim order to the commission saying, “do not immediately implement the decision to sack people’s representatives.” Following this, almost all of the punished representatives moved the court and have now returned to work. Looking closely at the supreme court’s various order, it seems to given importance to two particular concerns.

But if we leave aside a few exceptions, almost all of the representatives punished by the party and the commission have returned to work following the apex court’s interim order. For the first few cases, the court issued an interim order to the commission saying, “do not immediately implement the decision to sack people’s representatives.” Following this, almost all of the punished representatives moved the court and have now returned to work. Looking closely at the supreme court’s various order, it seems to given importance to two particular concerns.

First, the “condition where the people’s representatives assume office” and “quitting the party”. The constitution’s articles 215 and 216 haven’t imagined any other way the post of the local level representatives would be vacant other than a) they resign, b) they complete their tenure c) they die. It seems, with this, the constitution wants to strenghthen the local level representatives. That’s why, the apex court has compared the provision for local representatives with that for federal lawmakers and provincial assembly members.

The constitution’s articles 89 and 180 have provision related to federal lawmakers and provincial assembly members. Both these articles state that, for conditions where the positions become vacant, “if the party under which the representative was elected notifies that they quit the party as per federal law, the position of the federal lawmaker/ provincial assembly member will be vacant.”

But supreme court has said that no such provision exists for local level representative, questioning the worth of the provision on quitting at the act related to political parties. “The constitution doesn’t seem to have imagined the situation of local representative’s position becoming vacant after they quit their party,” says an order issued by a bench of judge Nahakul Subedi on the case of Suresh Kumar Thapa, chair of Champadevi-6 in Okhaldhunga. “In this situation, the section 6 of Political Party Act 2073’s methodology doesn’t appear clear.”

This debate’s second issue is related to the use of the 2073 Act. The supreme court, hearing another case, has questioned the very provision and methodology in the use of the Act.

Hearing the case filed by Mahadev Singh Dadal, an order issued by judges Dr Ananda Mohan Bhattarai and Hari Phuyal says, “What would the election commission do if the provisions of the Political Party Act’s section 32 (1) are fulfilled or not? Whether the commission should examine or not if a political party recommends fulfilling the provision or not?”

Another order issued by judge Dr Kumar Chudal upon hearing the case of deputy mayor Geeta Devi Sah of Yamunamai Rural Municipality also argues along similar lines. The order states that if a local representative is punished by the party and the commission without fulfilling the criteriaM, it would cause an irrevertible damage.

Thapaliya says his office can’t do anything since the Act was formed without paying attention to the constitutional provision. “The election commission hasn’t spoken anything so far about amending this law. Now once the Political Party Act gets amended, the commission can raise this issue as well. Many have questioned if the commission can follow the consititution instead of the Act. But the commission can’t do anything because the provision is enshrined in the Act.”