How a cabal of moneylenders and real estate brokers have pulled six farmers of Kaski, a rich landlord of Kathmandu and a popular singer into debt trap, forcing them to give up their property.

Rudra Pangeni: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

CHAPAKOT, Kaski – When Balaram Adhikari, a farmer in this village by the Phewa Lake, toyed with the idea of setting up a grocery here 18 years ago, he had little options. He is 61. He himself didn’t have enough funds. His village also lacked bank or cooperative that could have supported him. His neighbours had taken loan to raise cattle from a Pokhara cooperative called Nepal Sahakari Sanstha Limited. The cooperative, which is a two-hour trek from his home, said it could issue a loan only after he pledged four ropani of his farmland as asset.

Adhikari eventually received Rs 85,000, though on paper his loan amount was Rs 1,00,000. That’s because he had to pay Rs 10,000 service fee and Rs 5,000 for the cooperative membership. The Maoist insurgency was at its peak, so the grocery faltered. Adhikari defaulted on the payment of his loan. So, he did what millions of young Nepalis do: he left his home to work as a migrant worker in Malaysia.

Soon, he was sending money from Malaysia to his wife Parbati Adhikari in Nepal. But after paying two installments, she couldn’t find the cooperative: it had vanished from the area.

The Adhikari family wasn’t the only one worried about the sudden disappearance of the cooperative. Kul Prasad Parajuli, a neighbor, had pledged 10 ropani of his farm land as an asset for a Rs 200,000 loan. From 2001 to 2004, six farmers from Chapakot had mortgaged 37 ropani of farmland for a loan of Rs 900,000 to invest in livestock and other small enterprises. While Devi Raman Chapagai had taken a loan of 3 lakh rupees, others including Krishna Adhikari, Khadga Raj Sunar and Gopal Prasad Parajuli had taken a loan of Rs 100,000 each.

Fourteen years later, the office of the cooperative was tracked down in Kathmandu. But the cooperative, which was mired in financial trouble, had already auctioned their land. They were shocked to realize that they had lost their farmland. “Call it property or source of livelihood, our farm was all we had. We panicked after we found out that we had lost it,” Parajuli said, sitting at his modest home in Chapakot.

According to the Cooperative Act of 1992, the cooperative should notify borrowers to repay loan before issuing 35 day recovery notice, which should also be published in all local government offices of borrowers. But the farmers learned seizure of their property 14 years after their properties were auctioned as cooperative published the recovery notice in newspapers not accessible to the borrowers.

Officers of the Nepal Cooperative assured the farmers that they would return the land if they paid the loan together. They travelled to Kathmandu to find out more and spent several months deliberating their options.

Finally, on January 11, 2019 all six farmers went to Kathmandu, where they enquired about the unpaid loan. Rakesh Singh, general manager of the cooperative, told them that they owed 2.5 million rupees. ”He ordered us to deposit 1 million rupees in his personal account as soon as possible,” said Kul Prasad Parajuli.

Singh handed a letter to the farmers, in which he asked them to pay the land tax and submit a recommendation letter from ward office to repurchase the land. Sensing trouble, the farmers wanted to deposit the money in the cooperative’s account. But Singh said the cooperative’s accounts had been closed. They met Nabin Pun, the chairman of the cooperative, who lives in Pokhara. Pun is the son of Uttam Pun, a politician with the Rastriya Prajatantra Party. Uttam Pun had been responsible for trouble at the Nepal Cooperative and Nepal Development Bank.

Nabin, however, told the farmers to only pay 1.5 million rupees. This further confused them, but they had to save their farmland anyway. When they called Singh before depositing the money, he told them to wait until a board meeting of the co-operative.

‘Give us back our home’

The farmers waited for the board’s decision. Meanwhile, the cooperative issued a notice in a newspaper and auctioned their land. The cooperative sold the land to Khayar Bharani Enterprises, a company with sole ownership of Dr Prem Pun of Om Hospital, for 1 million rupees. The farmers found it out when they returned with paperwork to transfer the land ownership in their name.

Six farmers who have been rendered landless due to loan taken to raise cattle. (from left) Balaram Adhikari, Kul Prasad Parajuli, Purnakhar Sunar (brother of borrower Khadgaraj Sunar who disappeared after taking loan), Devi Raman Chapagain and Krishna Prasad Adhikari.

The farmers were able to stop the liquidation of their asset after they registered complaints at Pokhara Metropolitan City, Land Revenue Office, Kaski and District Administration Office, Kaski, but the cooperative filed a case at High Court in Pokhara seeking a stay order to allow them to sell the land.

On July 16, 2019, the High Court ordered the Metropolitan city’s ward no 23 ‘to coordinate and find a resolution between the petitioners and the defendant, as there was a possibility of a resolution on the issue.’

After the local officials failed to resolve the matter, on July 22, 2019, the farmers visited the Department of Cooperative in Kathmandu, where they demanded that their land be returned. But, there was no response. They even reached out to Padma Aryal, the Minister for Land Management, Cooperatives and Poverty Alleviation, along with MPs from their area. In the third week of August, Minister Aryal held discussions with the cooperative, the Department of Cooperative and the farmers. The minister ordered the officials to return the land to the farmers, but her directive was ignored.

Kul Prasad Parajuli, a 56-year-old farmer, said, “We promised them to pay the loan and the interest and asked them to return our property, but they denied us.”

Two crimes

Nepal Cooperative has been found to have committed two serious crimes during the auction of the farmers’ land. Using right to information, CIJ-Nepal has obtained the documents submitted by the Nepal Cooperative to the Department of Cooperative using Right to Information. The documents show the cooperative had been hiding the auction notice even when the debtors presented themselves in the cooperative. On February 10, 2019, a day before Rakesh Singh handed the letter to the farmers to pay Rs. 2.5 million to get back their land, the cooperative had published an auction notice in Rajdhani newspaper.

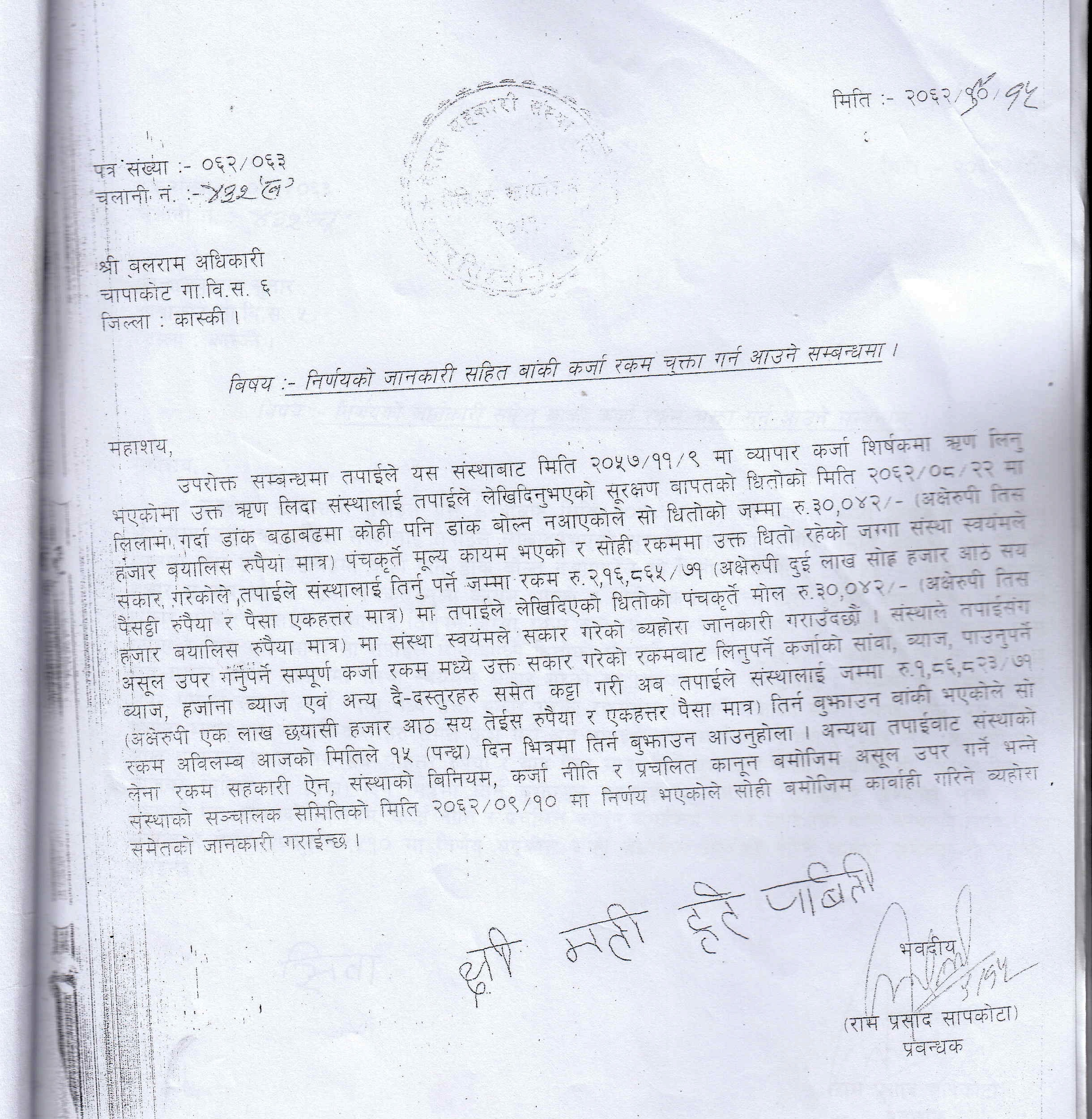

The document produced by Nepal Cooperative Limited during auction process 14 years ago has a signature of Parbati Adhikari, wife of borrower Balaram Adhikari. But Parbati claims she is illiterate.

By doing so, it violated the Cooperative Regulations 2018, which requires the lender to notify the debtors before auctioning their property. “To not share information to debtors while they were present in the cooperative is not only against the value of the cooperative, but is also an attempt to seize the property. People are losing their property because the recovery notices are issued by the lender without informing the debtors, who have no way of knowing it,” said Bishnu Prasad Timalsina, general secretary of the Forum for Protection of Consumer Rights.

The cooperative had also found to have faked the farmers’ signature. The cooperative staff had forged signature of farmers the cooperative to complete the auction process of the farmers’ property. Parbati Adhikari, wife of Balaram Adhikari, does not know how to read and write, but Nepal Cooperative submitted her signature to the Department of Cooperative. Showing the letter, Adhikari said, “I don’t know how to sign a document.”

“After the famers visited the cooperative to repay their loan, the officers illegally seized their property,” said Durga Bika, a lawmaker from Kaski in the federal parliament.

When asked why the cooperative sold the farmers’ land, Nabin Pun said: “We summoned them to our office several times, but they didn’t come. So we sold it to Dr. Prem Pun in 3 million rupees.”

Shashi Kumar Lamsal, a deputy registrar for the Department of Cooperative, said, “We couldn’t help the farmers of Chapakot get their property back because the cooperative had already completed the auction.”

A deer’s downfall

It’s not only farmers who have been snared in the cooperative’s trap, popular singer Ram Krishna Dhakal also lost his house due to a cooperative in Lalitpur. Dhakal once composed a song about a deer’s downfall (Orali Lageko Harinko Chal Bho), but he now finds himself in similar circumstances, thanks to Shree Laliguras Multipurpose Cooperative.

Ten years ago, Dhakal took a loan of Rs. 180 million from Laliguras Multipurpose Cooperative to buy a house in Bhaisepati area of Lalitpur under the name of his wife Nilam Dhakal (Shah). He also had put Rs 3 million from his saving to buy the house. After a few months, he could not repay the loan. He tried to pay off all debt by selling the mortgaged house, but he could not do it. Laliguras’s chief executive officer Surendra Bhandari did not meet him when he sought the cooperative’s consent to sell the house. Later, he was saddled with an additional loan of Rs 5.6 million from the cooperative.

Two and a half-storey house of Singer Ram Krishna Dhakal which has already been auctioned by the Shree Laligurans Cooperative.

“There was no option except to take additional loan when you could not sell your house,” said Dhakal. To saddle a borrower with an additional loan to pay off the debt is to ensnare him or her into a debt trap, according to advocate Bishnu Timilsina.

Dhakal learned about the auction, but he was on a musical tour in Europe. Though he requested the officers to not issue the auction notice until he returned to Nepal, the cooperative went ahead. Citing lack of interest from auctioneers, the cooperative itself bought the house. (Picture of the house).

Dhakal finds holes in the valuation of his property. “I borrowed 180 million rupees to buy the house, but the cooperative bought in 150 million rupees. How come its price fell after four years? Real estate prices have never fallen in Kathmandu,” he said. When Dhakal visited the cooperative to talk about the discrepancy, Bhandari declined to meet him.

Dhakal filed a case against the cooperative in Lalitpur District Court. Since there was no legal provision to calculate the amount owed and the amount to be paid, the court ruled that legal recourse can be delivered if the cooperative claimed the amount again.

Despite the injustice, Dhakal moved quietly to his old home. Suddenly, on August 7, 2019, Laliguras issued a notice in Kantipur daily stating that Dhakal and his wife should pay Rs. 49.3 million.

The following week at a press conference of people who had been cheated by the cooperative, Dhakal accused the moneylender of damaging his reputation. “When even people like don’t get justice, what will happen to other people? This co-called Nepal’s largest cooperative has victimised 300 people,” he told the press conference.

Consumer rights activists say that the government has failed to provide justice to victims such as Dhakal. “There are many other cooperatives like Laliguras. These are new loan sharks,” said Ganesh Giri, National Economic and Financial Service Consumers’ Association, Nepal.

CEO Bhandari claimed that Dhakal’s statement in this regard is totally wrong. “We waited him to pay back the loan for years but he did not turn up. We had also tried to protect him by issuing additional loans to postpone the auction,” said CEO Bhandari adding that the cooperative only followed the law to recover the loan.

Eye on prime property

Keshav Puri of Bhanimandal area of Lalitpur is another victim of Laliguras Cooperative. In early April 2010, Puri, in partnership with a friend, took a loan of 19 million rupees from Laliguras to buy a plot of 4 ropani and 7 ana land. For the first 6 months, he regularly paid the monthly installment. When he could not pay, he planned to sell the land and pay off the debt.

Despite finding a buyer, the cooperative resisted his attempt to sell the land. Bhandari, the CEO of the cooperative suggested him to put his plot of land (seven ropani) in Godavari as collateral for the same loan (Puri regrets the fact that he failed to ask how Bhandari knew about his property in Godavari).

Four years later, the cooperative auctioned all of Puri’s 11 ropani land. Puri learned about it from his friends six months later. When he enquired about it, the cooperative refused to provide the information. “When the cooperative valued the property, the price was 650,000 rupees per ana, but it was auctioned in 150,000 rupees per ana,” Puri said.

Devastated from the loss of property, Puri ran from pillar to post to file the complaint. He sought help of Keshav Badal, a lawmaker and the President of the National Cooperative Federation, Commission of the Investigation of the Abuse of Authority, Nepal Rastra Bank and Central Investigation Bureau. He didn’t get justice. He also missed the deadline to file a case at the court.

“The cooperative captured my land, whose price was several times more than the amount I had borrowed from them,” Puri said. In the notice issued to singer Dhakal, the cooperative has also asked Puri to clear the outstanding dues.

Referring the case of Puri, CEO Surenda Bhandari said, “Borrowers do not pay back loan and tend to complain of injustice after their properties are auctioned off legally.”

Gauri Bahadur Karki, a former judge who headed a high level investigation on troubled cooperatives in 2013, expressed concerns over the structural problem facing the sector. “Politicians have used cooperatives as a tool to collect money from people. They don’t want the sector to be regulated because that means they will not have a free hand on using people’s money,” he said.

From riches to rags

Not long ago, Ganesh Awale used to be a rich landlord of Baneshwar area in Kathmandu, But today the 74-year-old has lost almost all of his property due to real estate brokers who used his property to make profit.

In 2005, Awale had signed a contract with his tenant Narayan Karki to build an apartment in his property in Baneshwar. A year later, Karki said he needed loan to build the apartment. He persuaded Awale, who is illiterate, to sign a document transferring the ownership of his property (four ropani 8 ana) to Karki. The property was transferred to Karki’s business partner Praveer Shamsher Rana.

Manoj Kumar Mishra (who was also a board member of Nepal Electricity Authority in 2013) bought the land from Praveer Shamser for Rs. 2.3 million.

Mishra opened a company called Prama Developers Pvt Ltd and registered the land in the company. The next day, he mortgaged the plot to take Rs 37.2 million loan from Kumari Bank. It’s not clear why the money was borrowed. The ownership of the company (with such a large amount of debt) saw a series of transfers from Chandra Kumar Karki (Narayan Karki’s brother) to Santosh Khanal to Arun Lal Shrestha to Suresh Raj Ghimire. Ghimire sold some of his shares to Rameshwar Thapa. Then, both sold their share to Nanda Kishore Basnet (currently Chairman of the Industrial Area Management Limited of the Ministry of Industry).

No one paid the loan. In July 2014, Kumari Bank issued recovery notice for the land. Awale finally found out that he had lost everything.

This case has a familiar echo in one of the most high-profile land scam in Kathmandu. The powerful land mafia had repeatedly sold the 114 ropanis of land close to the prime minister’s residence, even as the Prime Minister appeared to be unaware about it.

The officers of Land Revenue Office have been involved in both cases. The government has barred transaction of the land in Baluwatar. It’s not clear whether the PM will get his land back. Awale also faced similar predicament. There are 27 cases related to this in the court, including a case of property division in the family.

Various banks have issued loans of Rs 2.25 billion after mortgaging the plots of Baluwatar. Similarly, four banks have issued loan of around Rs. 290 million on the land belonging to Awale. Clients are eligible to mortgage their land for loan only 6 months after the purchase and it takes at least 1 week of processing the loan application process the loan. However, the loans are issued on the next day of purchase on the disputed land. And the loan amount was more than the price of the land. Moreover, it’s illegal to issue loan on the land whose owners face a court case.

On September 17, 2014 Ram Krishna Humagai of Kavre paid Rs. 715 million for Awale’s land in an auction. He established a company called RKH Developers Pvt Ltd and registered the land in the company on October 13, 2014. The next day, Humagai took a loan of Rs 98 million (which is 37 percent more than the value of the land) from International Development Bank (NCC Bank after the merger). A head of loan department at a commercial bank said on the condition of anonymity, “We are not allowed to issue loan amount exceeding the value of the property. It’s possible only through collusion.”

Humagai even influenced powerful government officials to evict the Awale family from the land. Humagai sold the land to Kalu Gurung, chairman of Roadshow Real Estate Pvt Ltd, a real estate compny. Gurung bought the company (along with its land property) for Rs 200 million (Rs. 4 million in cash and the rest on credit). The next day, he mortgaged the land and took a Rs 138.7 million loan to develop plots in the land from Nepal Bangladesh Bank in Bijulibazar. After getting partial release for 7 ana of the land, Gurung sold it to two buyers. Prabhu Bank, Anamnagar issued a loan of Rs 12.3 million on the land. The officials of Nepal Bangladesh Bank didn’t reply to questions on why the bank issued loan on a disputed land.

Mukunda Kumar Chhetri, head of the Supervision Department at Nepal Rastra Bank said, “Banks cannot issue loan on a disputed land. If the debtor fails to repay the loan, how is it possible to auction it?” Chhetri added, “If loan has been issued several times, but it hasn’t been utilized, then it can be a case of money laundering. We will look into the matter.”

Awale now lives with his grandchildren at his dilapidated house at the edge of the plot. “I retired with a pension after serving at Minbhawan Campus. I had signed the contract with the builders so that I could build a nice house,” he said. “They turned out to be fraudsters. Where shall we go now?”

Note: 1 ropani is equal to 508.73 square meter or 0.125 acre. Rs 114 is approximately equal to a US dollar

Pangeni is @BerthaFN Fellow. This report is prepared by the Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal with support from Bertha Foundation.