According to the US Labor Department, approximately 300 Nepalis have filed compensation claims for deaths or injuries in the US war zones. However, experts believe the true number of Nepali casualties is far higher.

Peter Gill and Janakraj Sapkota: Center for Investigative Journalism, Nepal

Kathmandu: Kamala Thapa, of Bakrang, Gorkha District, was married and a mother by age 19. As her baby daughter was tottering around their village home and speakingher first words, tragic events halfway around the world changed both mother and daughter’s lives forever. In late August 2004, militants from the Ansar Al-Sunna terrorist group kidnapped and executed 12 Nepali migrant workers in Iraq. Among them was Kamala’s husband, Jit Bahadur.

Kamala’s daughter, who was 22 months old when her father was killed, is now a Class 11 student in Kathmandu. Sixteen years after losing her husband, Kamala says, “When I hear about Nepalis today who continue to go to work in conflict zones like Iraq, and they get injured or killed in attacks there, the memories come back. I can’t read those types of news stories — I just skim the headlines.”

The 2004 murders were seared into Nepal’s national memory by a video that went viral through shared VCDs, memory cards, and public screenings. (In those days, YouTube was not yet widespread.) A government investigation committee formed soon after the murders found that the Kathmandu-based Moonlight Manpower Company had tricked the men into going to Iraq, promising jobs in Jordan instead.

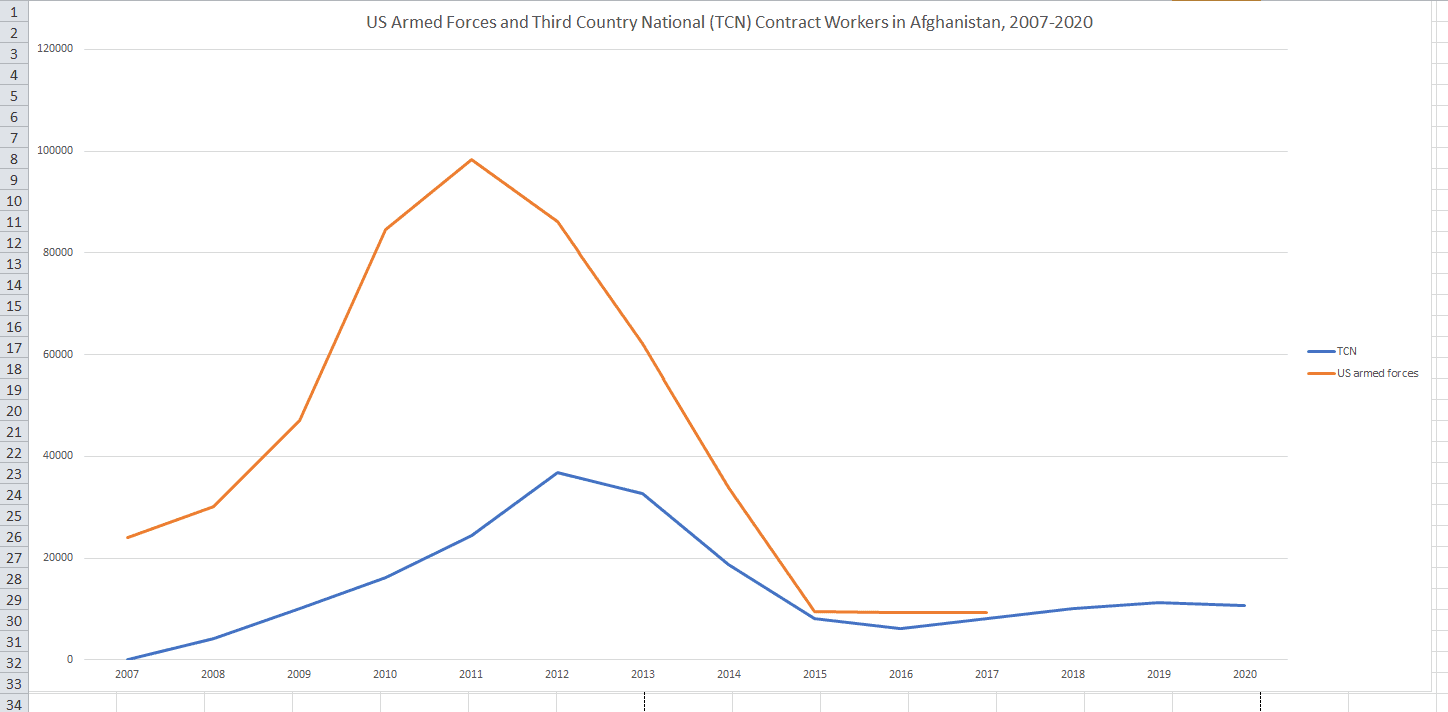

Chart showing the number of US armed forces personnel and Third Country National workers deployed in Afghanistan, 2007-2020, based on data from US Central Command and the US Congressional Research Service. After 2017, the US military stopped publishing troop levels. Chart by Peter Gill.

Tens of thousands of angry protestors took to the streets in Kathmandu, ransacking and setting fire to the manpower agency as well as dozens of other offices. Others used the opportunity to lash out at Islam by attacking mosques, Middle Eastern embassies, and even Gulf airline offices.

Few Nepalis were aware that the American military and a large American corporation had also played an important role in the Nepalis’ deaths. Months later, it emerged that the men had been destined for work for the military contracting corporation Kellogg Brown and Root, or KBR, on an American base in Iraq. A year later, the men’s families sued KBR for compensation for their loved ones’ deaths. After a long legal battle, the families eventually won their compensation case in 2008.

Following the incident, the Nepali government banned citizens from working in Iraq. However, many tens of thousands of Nepalis have ignored the ban and traveled to both Iraq and Afghanistan since 2004 to work for US contractors. When these workers are injured or killed, most do not know they are entitled to compensation, and their employers often deny them proper benefits.

Today, lawyers are assisting Nepali victims from American war zones to exercise their legally-mandated right to compensation.

Fighting the military-contractor nexus

In 2004, after seeing the videotape of the 12 murders, many people wondered: what were the Nepali men doing in Iraq? We know the answer thanks to Cam Simpson, an American investigative journalist at the Chicago Tribune newspaper.

Through extensive research in 2004 and 2005, Simpson found that the men had been sent to work for a sub-contractor of KBR, a corporation with deep ties to the American military and politics. (Former Vice President Dick Cheney was once CEO of KBR’s parent company, Haliburton). KBR supplied and managed US bases throughout Iraq, hiring workers from all over the world as cooks, guards, drivers, mechanics, janitors, and for other positions. Through sub-contracts with a Jordanian firm and a Kathmandu-based manpower agency, KBR had recruited the Nepalis to work at the laundry service on the American Al-Asad Airbase in Western Iraq. The men were on their way from Jordan to their new jobs when they were kidnapped by Ansar Al-Sunna militants.

As part of his research, Simpson traveled to Nepal and met Ganesh Gurung, an academic at the Nepal Institute for Development Studies. (Today, Gurung is a member of the government think-tank Policy Research Institute). Gurung, who researches migration, helped Simpson locate the victims’ families.

Dr. Ganesh Gurung and Mathew Handley. Photo courtesy of Matthew Handley.

Three of the 12 men came from a destitute village near Janakpur. “They lived in a little hut. One mother was partly paralyzed,” says Gurung. “I cried when I saw how they were living. I thought: the men migrated abroad to escape this poverty, only to die in Iraq!”

After her husband died, Kamala and her daughter moved to Kathmandu, where they lived at the Tulsi Meher Ashram. Remembering that time in her life, Kamala says, “I didn’t know anything about my rights. I had no idea my husband’s employer owed him compensation.”

After Simpson published his story in the Tribune in late 2005, the case received public attention in the US. Soon, Simpson put Gurung in touch with a team of American lawyers who said they could help the families.

The team, from the Washington-based law firm Cohen Milstein, was led by the human rights lawyer Agnieska Fryzsman and supported by a young lawyer named Matthew Handley. Handley had been a Peace Corps Volunteer in Nepal in the 1990s, helping villagers build latrines. He spoke Nepali and was familiar with the hardships of migrant Nepalis abroad, though he had never encountered a case so egregious as the 12 murdered men in Iraq.

With the help of the American lawyers, the victims’ families filed compensation claims against KBR, its Jordanian sub-contractor, and their insurance company demanding compensation under an American law known as the Defense Base Act (DBA). The DBA requires US government contractors and sub-contractors in war zones to buy special insurance that will compensate employees for injuries and deaths. It sets standards for compensation based on formulas that take into account the type of injury, the employee’s salary, and the number and age of family members the employee supports.

Gurung spent months traveling around Nepal collecting the beneficiaries’ necessary bio-data to file the claims: birth certificates, marriage records, and other official documents. He shared these with the lawyers, who then submitted them to the US Department of Labor along with applications for compensation.

According to Handley, compensation cases usually move for when all the proper documents are submitted to the Department of Labor. However, KBR’s insurer challenged the 12 Nepalis’ claims, arguing they were incomplete because they did not include the men’s contracts — which had been lost.

As a result, the case moved to administrative court. Fortunately, the victims’ lawyers were able to prove the men were working for KBR based on strong circumstantial evidence, including testimony from a man who had been trafficked to Iraq with the 12 but who was in a different vehicle, and therefore made it to Al-Asad alive.

In 2008, the American court ruled in favor of the Nepalis. Nine of the 12 families received compensation, but three did not because the victims were unmarried and had no living parents (under US law, siblings are not eligible beneficiaries).

Fryzsman and Handley also filed a separate case in US federal court against KBR for human trafficking, since the 12 Nepali men had been tricked into going to Iraq. Ultimately, they lost this case — not for lack of evidence, but because the court decided it did not have proper jurisdiction for the case.

Many new cases

The victory in the 12 Nepalis’ DBA case marked the beginning of a long and productive partnership between Gurung and Handley. According to Handley, the duo have since won compensation for over 30 Nepali victims from Iraq and Afghanistan, including deaths and injuries.

Because there is no time limit for filing cases so long as the employer never reported the incident to the American government, Handley has been able help disabled workers even years after their injuries occurred. For some victims, the compensation came as a godsend long after they had given up hope.

With her compensation money, Kamala bought land and built a small home in the Buddhanilkantha neighborhood of Kathmandu. She sends her daughter to a good college in the city, and runs her own tailoring business. “I wouldn’t have had any of this had we not won the compensation case,” she says. “I owe it all to [Gurung and Handley].”

Suraj Lama, who was injured in an insurgent attack on a base in Iraq, with his mother in Rajahar, Nawalparasi. Lama says he went to Iraq in search of economic opportunity. Photos: Peter Gill

Another of Handley’s clients, Suraj Lama, went to Iraq in 2005, just a year after the 12 Nepalis were murdered. Unlike the 12 men, the 21-year-old Lama chose to go to Iraq. After losing his father the previous year, Lama went hoping to earn enough money to support his mother back in Rajahar, Nawalparasi. For a while, Lama worked for a catering company at the Al-Asad Airbase, where the 12 men would have worked had they survived their journey.

Dissatisfied with the salary, Lama later took a new job with a different company managing trash at a landfill on another American base, Al-Taqqadum, near the Iraqi city of Fallujah. On October 2, 2008, Lama was at Al-Taqqadum when he was struck in the abdomen by a bullet or missile fired by Iraqi insurgents. He was rushed to a hospital, underwent surgery, and then spent several months convalescing.

“The last thing I remember was an explosion and a lot of dust or smoke. When I regained consciousness, I was in the hospital and a week had passed by,” says Lama.

Eventually, his company, the Dubai-based Blue Marines Services, sent him back to Nepal with $5,000, crutches, and a nasty scar on his stomach. When Lama returned home to Nepal, he had a long scar on his stomach and had to use crutches to walk.

Lama struggled to recover. Pain in his pelvic area prevented him from working, and when he went to the UMN hospital in Tansen, Palpa District, doctors discovered a 1-inch piece of metal shrapnel still lodged in his lower back.

In 2011, Lama saw an advertisement Handley and Gurung had posted in Kantipur for a “Know Your Rights” workshop in Kathmandu, targeted at migrants returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. Lama went to Kathmandu with his contract and other documents to meet the American lawyer. Handley agreed to take on Lama’s case because the compensation Lama received did not appear to meet the standards set by the DBA. However, Handley soon discovered that Blue Marines Services had gone out of business — which led to years of delay.

Finally, in 2018, more than nine years after his injury, the US Department of Labor agreed to compensate Lama using a special government fund. For Lama, the money eased his worries.

“Now I can support myself and my mother, instead of begging from my brothers,” he says. Lama joined a local gym in Gaindakot, where he continues physiotherapy to strengthen the muscles injured 12 years ago.

Another client of Handley’s, Gunaraj Dahal, was injured in Afghanistan in 2008 while working for the American company Supreme Site Services. Dahal slipped and fell while carrying an air conditioner at the company’s warehouse in Kabul. With nerve damage to his leg and difficulty walking, the company sent Dahal home and fired him in early 2009.

“I arrived at the airport in Kathmandu in a wheelchair,” says Dahal. “I thought – is the rest of my life ruined?”

Handley filed an application for disability payment for Dahal under the DBA, and eventually negotiated a compensation settlement with the insurance company. Dahal started his own air conditioning repair service in Kathmandu, where he now employs four people.

“It’s the compensation money that made this possible,” says Dahal.

American legal teams

In addition to Handley’s current law firm, which is named Handley Farah and Anderson, several other firms also help non-Americans get compensated under the DBA. These include Handley’s old firm, Cohen Milstein, as well as Strong Point Law Firm and Barnett, Lerner, Karsen, Frankel and Castro, among others.

Suraj Lama at a gym in Nawalparasi, where he does physical therapy exercises for muscles injured in an insurgent attack in Iraq. Photo: Peter Gill

Typically, the employer or the insurance company pays the claimant’s lawyer’s fees if the claimant’s case is successful. If a compromise is reached through settlement, the fees are deducted from the victim’s compensation. However, all lawyers’ fees must be approved by the Department of Labor and no fees are paid if the victim loses the case.”

Sometimes, if the plaintiff is a victim of egregious abuse, the US government pays for his or her lawyer’s fees. For example, the government paid Fryzsman and Handley for representing the 12 murdered Nepalis in Iraq, so the victims kept 100% of their compensation.

Handley has also undertaken some cases pro bono. In 2012, in the memory of one of his clients killed in Afghanistan, Handley established the Thaman Gurung and Matthew Handley Scholarship Fund. According to Amanda Gurung, Member-Secretary of the Chandra Gurung Conservation Foundation, the parent organization that oversees the scholarship, the fund has provided scholarships for nearly a dozen underprivileged students in Kaski District for college-level studies.

Handley and Gurung say many Nepali victims remain unaware of their rights under the DBA. Indeed, employers often try to keep the law a secret from workers. Many victims have yet to start the process to receive their legally mandated compensation.

What should Nepalis who think they may be eligible for DBA compensation do?

“Ask for copies of all documents that you sign, or take photos with your phone,” says Handley. “Before leaving, ask what insurance exists in the event you are injured or killed.”

Gurung adds: “If you’ve been injured, don’t sign any documents you don’t understand, because you could get cheated. Find a good lawyer — someone who knows the American law and has experience — and get advice from them.”

Migration today

After the 12 Nepalis were kidnapped and murdered, the Nepali government banned citizens from traveling to Iraq in September 2004. The ban was briefly lifted in 2010, but reimposed shortly thereafter, and continues today. Most work in Afghanistan has been banned since 2016, after a bus full of Nepali security guards were killedby a suicide bomber in Kabul.

However, despite the bans, Nepalis continue to travel illegally to Iraq and Afghanistan to perform work duties that are, in many cases, essential to the American military’s operations. In Iraq, Nepali migrants have formed organizations such as the Nepal Migrants’ Society, Nepal Tamang Ghedung Kurdistan, Nepali Women’s Society Kurdistan, Kurdistani Migrants’ Nepali Society, and the Non-Resident Nepalis Association of Iraq.

The president of the latter association, Lalkaji Gurung, estimates that there are currently around 15,000 Nepalis in that country, of whom around 5,000 work on various US bases. Experts estimate that to date, close to 50,000 Nepalis have worked in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Illegalizing migration doesn’t stop people from migrating. It just makes the degree of vulnerability go way up,” says Gurung.

US Department of Labor data show that only around 300 Nepalis have ever filed compensation claims under the DBA. Gurung says he thinks the actual number of Nepalis injured and killed is far higher.