Nepal Army demolished the historic Tri-Chandra Military Hospital and replaced it with a commercial building. The army first built it without securing an approval for its design and is now pressuring Kathmandu Metropolitan City to issue a completion certificate. An expose of how military is driven by profit-making.

Rameshwar Bohara: Center for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Tri-Chandra Military Hospital in 1982 BS. The hospital built for the treatment of Nepalese soldiers affected during World War I by British government has been destroyed by Army for commercial business complex. Photo courtesy: Madam Puraskar Library

In a few days or weeks, a business complex will open its doors to public in Kathmandu. This is no ordinary mall. Armed soldiers will provide security to the building. The Nepal Army built the nine story modern building, which rises at the heart of Kathmandu in Mahankalsthan (New Road) near National Trauma Centre, for commercial purpose. The Army headquarters has issued a public bidding to rent out the building. According to the bidding, the building will be rented by the first week of Magh.

The business complex area had previously been occupied by Tri-Chandra Military Hospital. Around 3 years ago, Nepal Army demolished the 89-year-old building and replaced it with a modern complex with amenities. Three years ago, when the Army demolished the building, it said it was going to retain its name and build a modern hospital for treatment of current and former soldiers, their families and civilians. It also claimed that the hospital will not be for profit and will provide medical care to those in need.

But as soon as the construction completed, the Army decided to rent out the complex. Why did the army demolish a historic building and make way for a commercial complex? An investigation into this case has revealed that the Army is after money and is openly disregarding provisions to meet its goal.

Eye on money

On its website, Nepal Army has the following description of its venture: “Complete the construction of the under construction 459-bed Tri-Chandra Military Hospital (Veterans and Civil) and operationalise it to make free medical service to serving soldiers and veterans and their families more effective and to provide free medical care to civilians.”

On September 10, 2017, the Army had already called for a rental bid for the commercial complex. According to the bid, the complex covers an area of 315000 square feet in Mahankalsthan. Of that, 35,000 square feet has been allocated for the treatment of the beneficiaries of Army Welfare Fund. The remaining 260,000 square feet including the nine-story building, basement and other structure in its premises is being offered to a firm, individual or company.

In other words, of the 30,000 square feet allocated for hospital, only 9.52 percent of floor space is set aside for medical treatment. It may seem like the area is being offered to the hospital. But the Army has made it clear that the area is not for the hospital, but for a policlinic. “We will provide services such as MRI, CT scan and lab tests for soldiers and their families, but patients will not be admitted here. They should be refered to our hospital in Chhauni. Aside from policlinic, the building will be rented out,” said Nainraj Dahal, a spokesman of Nepal Army.

Though Tri-Chandra Military Hospital was Nepal’s first military hospital, after 1990, the Army shifted its services to Chhauni hospital. Birendra Army Hospital at Chhauni began to serve as a military hospital. The hospital at Chhauni provides soldiers and veterans and their families free medical services including MRI, CT scan and lab tests. Why did the Army plan another big hospital building while it already had a modern hospital at Chhauni which could have been expanded?

The information on Nepal Army’s website “Tri-Chandra Hospital to have total beds of 469” has been removed.

According to some army officers, the new building was never intended to be a hospital. “Because the Army couldn’t say that they were building a commercial complex, they demolished the old building saying a new hospital would replace it,” a major general said. “Fearing allegations against the Army for entered intos business, they try to defend by including a policlinic. But it doesn’t make any sense. It’s a business complex operated by the army, not a hospital.”

At present, three buildings have been completed. The Rs. 2 billion fund for the construction of these buildings came from the Army Welfare Fund, according to the Nepal Army. The Fund was set up in 1975 with funds collected from Nepal Army soldiers deployed at United Nations Peacekeeping forces around the world. But the Army is using the funds for profit-making businesses as well as for charity works.

Until July 16, 2017, the Fund had a savings of roughly Rs 35 billion, according to information provided by the Army at a press conference on August 6, 2017. If you add the Rs 5 billion the Army has invested from the Fund, its current savings is around Rs 40 billion. The Army said it uses the fund for health service, education, relief, insurance, housing and vocational training. The fund for construction of the commercial complex in Mahankalsthan was also drawn from the Army Welfare Fund in order to provide health service.

But the real motive behind the decision seems to be to hoodwink the authorities. After the building was completed, the Army decided to rent it out. “Our military hospital is at Chhauni. It was difficult for us to move human resource from there to the new building. We couldn’t provide services due to lack of space,” Dahal, the Army spokesman, said. “We want it to make profit because we have used money from the Fund. We realized that it was beneficial to lease it than to run a hospital.”

Nine story building sans permit

According to Local Self Governance Act (1999), approval of a building design is required for any building within Metropolitan City or municipality from related authorities. Kathmandu Metropolitan City is the authority that grants permission for such buildings. But even as the Army prepares to rent out the building, it hasn’t secured the necessary building permit. The Army has also failed to receive the building design approval from Kathmandu Metropolitan City.

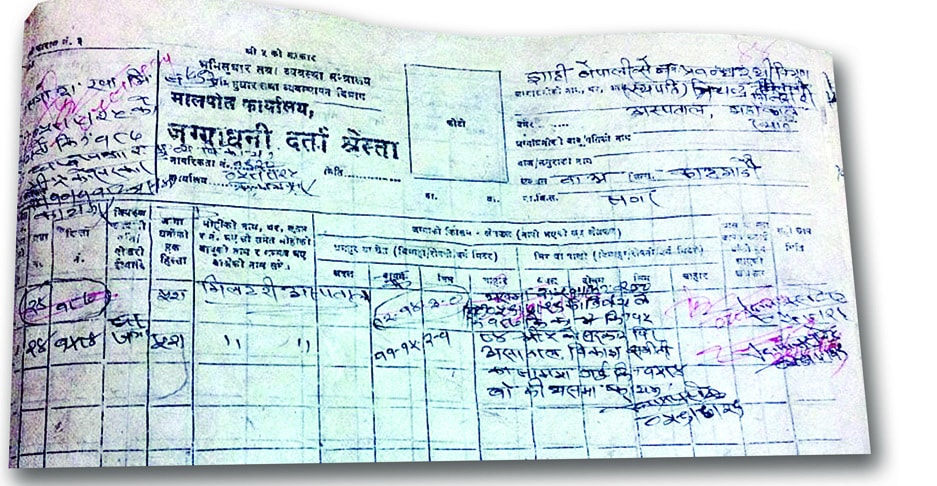

The record of land in land registration office .

When the Army began constructing the commercial complex, Kathmandu Metropolitan City enquired the Army headquarters about it. After the Army ignored the query, it asked the army to furnish a building permit. Despite following it up and informing the Defence Ministry about the matter, the Army neither sent a response nor did it comply with the rules. “We followed it up several times, but they didn’t even reply verbally,” said Ram Bahadur Thapa, head of Building Permits Section at the Metropolitan City.

Due to security reasons, some army structures need not apply for building permits. That includes VVIP residences of President and Prime Minister as well as army and police buildings. They are not required to present designs because it might lead to breach of secrecy, though details such as length, width, number of floors are needed. For example, the new residence-cum-office of the President was recently built following this process. And, that’s due to the security reasons. But the President’s Office had furnished some details about the building to the Metropolitan City. The design for the building was approved after the authorities received required information.

The Metropolitan City had even urged the Army headquarters to provide some details of the building. “If the Army had sent us those details, we would have approved it. But the Army kept ignoring our requests,” Thapa said.

The Army-built commercial complex is not among buildings classified as sensitive for security reasons. It is neither within the premises of the Army headquarters nor is it housing armed forces. Even for a hospital building, such details should not remain secret. In fact, this was a commercial complex. But despite the precedence of President’s residential building securing necessary permit, the Army failed to comply with the provision. Officials at the Metropolitan City said the Army hasn’t secured building permit for any of its buildings.

This is not the only non-compliance from the Army. After construction of a building, it is mandatory to secure a completion certificate. One cannot use the building unless such certificate is secured. At present, such certificate is required even to install water supply and electricity. The commercial complex hasn’t even secured a building permit. So the completion certificate is still yet another step. But without all the necessary compliance, the Army has already issued calls for renting the complex.

Flouting the rules

The district where the Army built the commercial complex is part of the core city area. There is a separate building code for the core city area. Buildings that are more than five-story are not allowed in the area. Building Code of 2009 says, “Buildings in the area must not exceed 45 feet or 13.7 metre.”

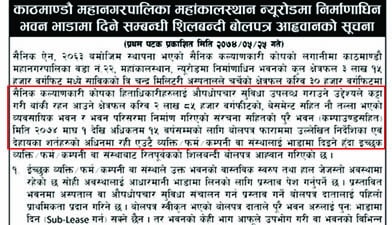

Invitation of bids issued by Nepal Army for renting building for commercial use on Sept 10, 2017

Despite such restriction under building code, the Army built a nine story building with a basement. The Metropolitan City warned the army that it must comply with the rules for building, but the Army headquarters just ignored the warning.

The Metropolitan City had planned to demolish buildings that flouted the rules for building permits. But after authorities found out that the Army was one of the offenders, the plan had been postponed. “Other building owners who flouted the rules have urged us to take action against the Army first. This has exacerbated the problem,” said Ram Bahadur Thapa, head of Metropolitan City Building Permit Section.

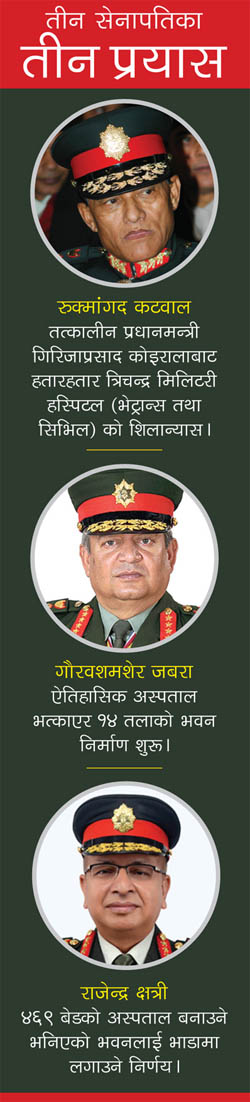

The new building at Mahankalsthan was originally planned as a 14-story structure. The foundation was laid accordingly. But the April 2015 earthquake struck even as it was under construction. Soon after, the Army leadership changed. Rajendra Chhetri took over from Gaurav Shamsher Rana as the chief of army. Then, the design was scaled down. The Army zeroed in on a nine story building with a basement parking. “If there hadn’t been an earthquake and the army leadership remained the same, it would have been 14 stories high,” a military officer at the Army headquarters said. “The Army Chief would have gone ahead with the original plan. No one could have stopped him even though it violated the building code.” Dahal, the Army spokesman, said the Army scaled it down after realizing that it wasn’t going to make much profit despite huge investment from the Fund.

Then Army Chief Rookmangud Katawal had initiated work on the building. The plan was to spend Rs 3 billion in the project. But it didn’t move ahead. It stalled even during the tenure of Chhatra Man Singh Gurung. When Rana took the helms of the Army, the work progressed. It was estimated that the cost would be around Rs 6 billion. But the earthquake forced the Army to scale it down. It can withstand an earthquake measuring up to 10 Rector Scale, according to the Army headquarters.

Invitation of bids issued by Nepal Army for renting building for commercial use on Sept 10, 2017

Under the Settlement Development, Urban Planning and Building Construction guideline issued by Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development after the earthquake, the new building faces problem. That’s because the building comes under commercial complex or shopping mall. According to the new zoning and safety guideline, big buildings such an apartment or residential buildings, shopping complex or mall, department stores should have an Emergency Plan. It is yet to be seen how a building which was constructed without the mandatory building permit will fare in its emergency plan.

The land under the building belongs to Tri-Chandra Military Hospital. According to the Land Record Office of Dilli Bazar, the total area of the land was 11 Ropani 15 Ana 2 Paisa One Dam. A measurement of the land on August 1, 1977 put the area at 12 Ropani 14 Ana 3 Paisa. But a subsequent measurement found that the area was 11 Ropani 15 Ana 2 Paisa One Dam, which was established as accurate. At the time, all of it was demarcated as one plot under 187. But on December 10, 2001, the government transferred 9 Ropani 2 Ana 2.5 dam land to Bir Hospital. That’s where the National Trauma Center has its building now. The Trauma Centre’s plot number is 1583. The remaining 11 Ropani 15 Ana 2 Paisa One Dam came under Tri-Chandra Military Hospital, whose plot number is 1584.

The government is the owner of the land under Tri-Chandra Military Hospital. The land belongs to the Army because the hospital is part of the Army. In other words, the government provided the land to the Army. But the Army Welfare Fund isn’t under the government. Nor is the government responsible for the Fund’s work. A board runs the Fund and decides everything related to it. Though a secretary each from Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Defence are members of the board, the army officers hold sway over it. The board had decided to build a commercial complex on the government property.

Can the Army build a commercial complex on a government property? Moreover, can funds from Army Welfare Fund be used for a profit-making venture? We asked these questions to senior advocate Srihari Aryal. “The military hospital was a historic monument. It was a bad decision to demolish it. To build a commercial complex in that space is yet another mistake,” he said.

“Other democratic countries have clear jurisprudence on the role of national army. But in Nepal, both the government and political parties remain silent on matters concerning the Army,” he said. Aryal said a policy clearly defining the role of Army must be formulated. “This must be discussed in the parliament. Unless the issue is of strategic significance, both the government and army must be transparent about their activities,” he said. “The Army seems keen to enter into business in order to make profit. This will weaken democracy. Consequences can be huge if the Army goes out of control.”

Tearing down a treasure

The Tri-Chandra Military Hospital was built in 1925 with support from British as a tribute to Nepali soldiers who lost their lives and fought for the British during the First World War. Its history is entwined with Nepal’s military history. This was also the first hospital that introduced new technology such as fiber optic endoscopy and lab tests in Nepal.

The decision to demolish such historic heritage to make way for a new building was made by then Army Chief Rookmangud Katawal. Then Lieutenant General Kul Bahadur Khadka had opposed the decision, and defended saying it should remain as it was a historic heritage built by the British government.

Sensing opposition to the plan, Katawal quickly arranged for Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala to lay the foundation stone for the new building. But the work stalled. Between the tenures of Katawal and Rana, Major General Naresh Basnyat had continued to get involved in the project. Basnyat was a controversial figure in the army. During the demolition of the old building, he was close to Army Chief Rana. “Basnyat presented a plan in which the complex would be rented out, which will bring Rs 350 million a year. He had plans to pay back the construction cost from the lease in 5-6 years. This impressed the top army brass,” an army officer said.

When the Tri-Chandra Military Hospital was demolished, it was an 89-year-old building. Such old buildings carry immense significance. On top of that, it was a symbolic structure. Any structure that is 100 years old is considered a heritage. In order to demolish such structure, the approval of Department of Archaeology is required. But some structures don’t have to be 100 years old to be classified as a heritage site. The Department of Archeology classifies structures that represent a special period or with extraordinary architecture as heritages. They include Rana palaces, Singha Darbar, Shital Niwas, Bahadur Bawan. They not only represent certain historic period, but are also rich in architecture. “Tri-Chandra Military Hospital was one such building. The Army might have refered to the 100 year old theory to tear it down, but it was wrong. They failed to understand its history and our glory,” said Ram Bahadur Kunwar, a spokesman of Department of Archeology. Did his office try to stop the demolition? “We could have stopped it. But when we learned about it, it was already late,” he said.

The Army headquarters is now putting pressure on officials of Kathmandu Metropolitan City to issue a completion certificate of the building. Army officers visit the Metropolitan City Office, demanding to the officials to issue the certificate. They argue that they need it for banking purpose. “When we enquired about the permit, they ignored us. They failed to secure building permit. How can we provide them completion certificate when they don’t have the permit to build in the first place?” asked an official at the Metropolitan City.