Ramu Sapkota & S Vinothaa

Nepali recruitment agent, Rinji Rai, was found dead in mysterious circumstances at a worker’s dormitory in Nilai

On April 7, a cacophony of South Asian dialects resonated through the corridors of a workers’ hostel in Nilai, Negeri Sembilan, gradually fading as stranded workers poured out of the building and into an adjacent open warehouse.

One man did not join them.

On that day, Rinji Rai, 47, a Nepali labour recruiter who had flown to Kuala Lumpur three days before to address the unresolved work visa issue of his recruits, was found dead in the hostel toilet.

Malaysian authorities have ruled out foul play but Rinji’s widow, Indrasuwa Rai, 46, and the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agency believe he died of mysterious circumstances and want the case to be investigated as murder.

“There is a gang of people who sell demand quotas by showing big dreams to common businesspersons like Rinji. Rinji lost his life by falling prey to such a gang,” Sujit Kumar Shrestha, former general secretary of the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies, said.

Rinji had 20 years’ experience in the business and his agency Marvelous Employment Nepal Pvt Ltd, in Kathmandu, together with Rose Overseas PVT, recruited and sent 64 workers who later found themselves jobless in Malaysia.

Indrasuwa, now left to raise three children on her own, believes her husband was murdered based on the photograph and videos of him dead in the toilet, callously sent via Facebook Messenger to his family by a Malaysian recruitment agent.

“It clearly shows that it was not suicide but a murder, possibly by a criminal group,” she declared, adding that his body appeared like it was staged to look like a suicide.

In her letter to the Nepali prime minister, seeking his assistance, she said Rinji had paid 3 million Nepali rupees (RM107,502) to a Malaysian named “Ms Yeoh” to secure visas for his recruits but she allegedly absconded with the cash.

Two months before his death, he learnt his recruits were jobless in Malaysia and Indrasuwa heard him having a heated telephone conversation with Malaysian and Nepali agents over the matter.

Her brother Deepak said that Rinji also received “threatening” phone calls from agents, who said the only way to settle the dispute was for him to travel to Malaysia.

“So, he went to Malaysia. Just listening to the audio conversation provides clues to the intention of the caller,” Deepak said.

While Rinji lived his last moments, the stranded Nepali and Bangladeshi workers who had gathered at the warehouse believing they were to be rescued, had their hopes dashed.

The Labour Department officers and representatives from their respective country’s consular offices in Kuala Lumpur had few answers to the workers’ months-long unemployment.

“They told us to be patient. Next week everything will be all right.

“For months, we got the same answer from agents back home too,” said one Nepali worker who at the time he spoke to Malaysiakini in June, had already spent three months stranded, jobless in Malaysia.

The names and identities of all workers in this report are withheld or changed to protect their job security and from possible backlash from traffickers.

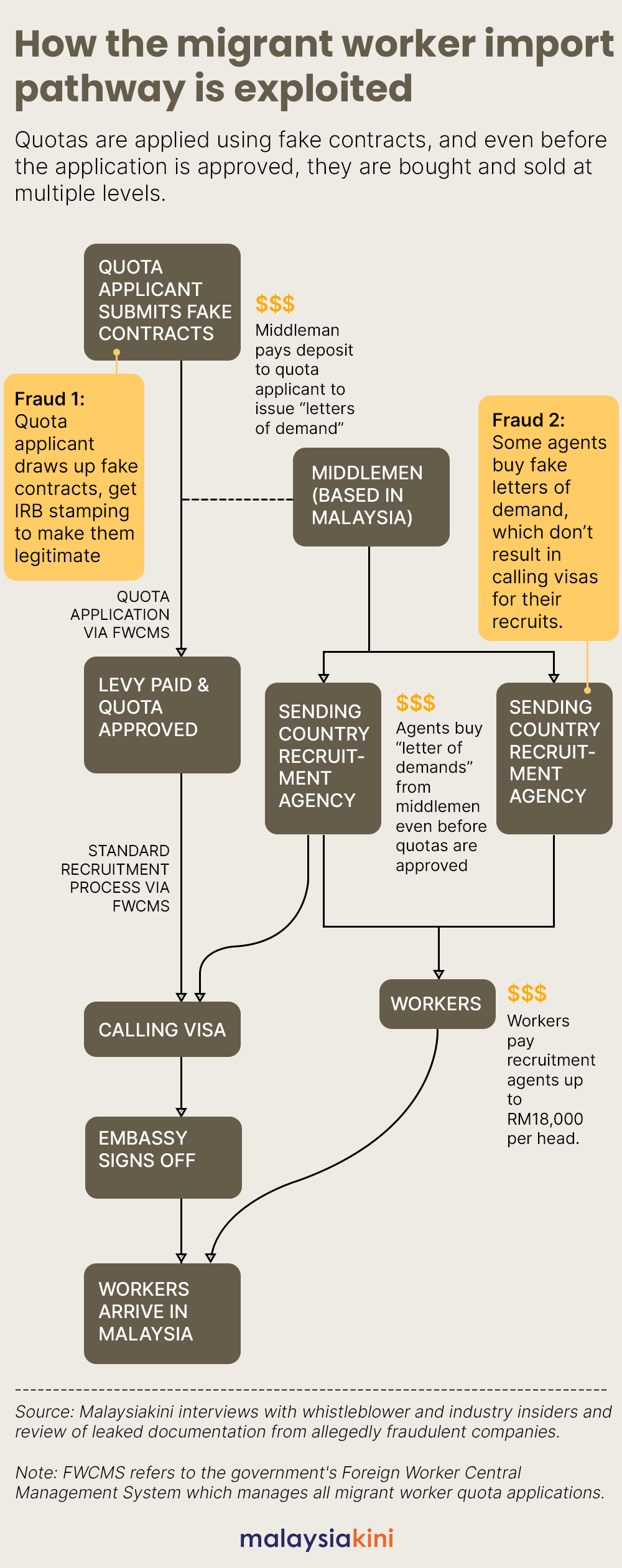

Death and quota fraud

Rinji’s mysterious death was not the only one in the debacle involving the import of migrant workers without any jobs waiting.

A couple of months before Rinji’s death, a Nepali worker brought in by the syndicate died at the same place, the Nepali Embassy told Reuters, but the cause of death was not disclosed.

The fact that the workers arrived to find no jobs waiting was a major red flag that something was amiss with the recruitment process.

To obtain these quotas, applicants must prove that they have a legitimate business and a need for the number of workers requested.

However, Malaysiakini’s investigations found hundreds upon hundreds of workers recruited under quotas obtained using fake documents.

Worse, these quotas were also traded, allowing companies who cheated their way to the quotas two avenues of income.

They could sell the quotas to other companies or agents, or sell or rent out the workers who had arrived via the trafficking scheme, interviews with insiders and defrauded workers reveal.

It is unclear how many such cases exist and the number of workers who were defrauded in the same way.

However, in just one syndicate uncovered by Malaysiakini, a group of six companies obtained quotas to recruit a total of 1,625 migrant workers for the services sector in 2022.

Collectively, the six companies had applied for more than 4,000 workers but received a quota approval of 1,625 workers, documents sighted by Malaysiakini showed.

After receiving quota approval notifications from the migrant worker division in the Labour Department, the companies settled the levy with the Immigration Department before the official approval letter was obtained.

The Immigration Department received approximately RM3 million in levy payments from these companies.

Dreams of Genting Highlands

Documents reviewed by Malaysiakini showed that the companies received quotas to import workers for cleaning services.

In Nepal and Bangladesh, recruitment agents were told cleaners are needed for resorts in Genting Highlands. The prospects of working at the resort town seemed so attractive that many workers paid recruitment brokers and agents large sums to secure the jobs.

Genting Highlands, where many of the duped workers thought they would be working.

One of them, Tilak (not his real name), had once worked in a garment factory in Malaysia and applied to return, hearing that the job would be in Genting Highlands.

“Since I had lived in Malaysia for some time, I knew that work was good at Genting Highlands. We came to Malaysia with that hope,” he said.

The first batch of demand letters was sent to Bangladesh and Nepal in August 2022 and workers started arriving in batches from January 2023.

As they processed the workers who arrived, the Malaysian staff, too, prepared to move to Genting for the job.

Some of them bought new clothes to dress for the cooler climate, but their boss kept postponing the operation team’s move to Genting Highlands.

The day never came.

‘Official stamp’

How were quotas for the import of 1,625 workers approved if such jobs never existed? The answer lies in a simple fraud, taking advantage of regulatory loopholes along the way.

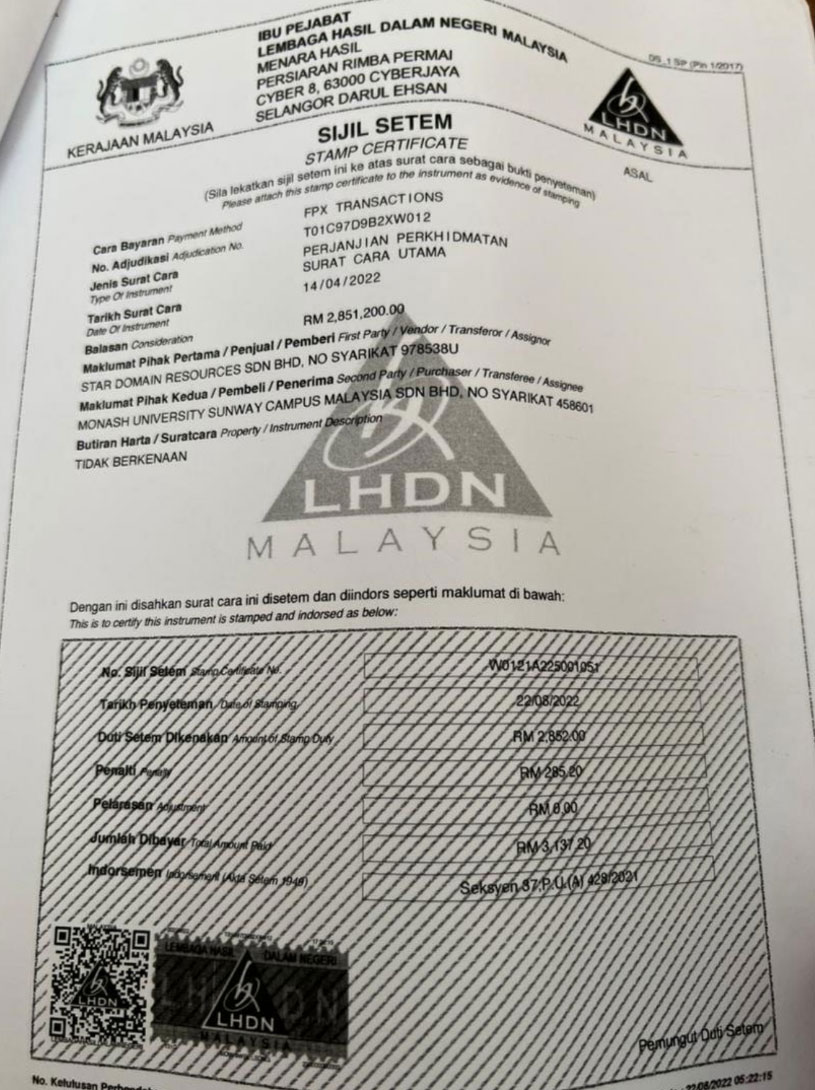

Labor agreement document between StarDomain and Tilak (name changed).

For example, Malaysiakini’s checks found the company Star Domain Resources secured quotas to import 980 workers in 2022 by showing that it had already secured contracts for cleaning services, worth millions of ringgit.

The contracts were accompanied by valid Inland Revenue Board (IRB) stamp duty certification, serving as a cover note, while the IRB confirmed the duties were paid up.

However, checks found the actual contracts do not exist.

Among them was a three-year contract worth RM2.85 million with “Monash University Sunway Campus Malaysia Sdn Bhd”.

When contacted, Monash said it had no such contract with Star Domain and lodged a police report on the matter. It added it has been known as Monash University Malaysia Sdn Bhd since 2013.

Despite making the contracts seem legitimate, the IRB said it has no obligations to verify information provided by stamp duty certificate applicants. This leaves a gaping chasm for exploitation.

“The onus of proof on the validity of the details in the contract is on the duty payer,” the IRB said in a written reply to Malaysiakini.

Further, there is no legal risk of submitting a fraudulent document for IRB stamping.

The Stamp Duty Act 1949 which polices fraud in Stamp Duty certification only addresses fraud in relation to duty payment punishable with fines that range from RM1,000 to RM5,000.

Old names

The syndicate also obtained IRB stamping for supposed contracts with fictitious companies, using the older names of companies, false addresses and false company registration numbers.

One company, Zouk Spa, did not exist at the address stated on the contract, and when contacted, its director Ow Kok Soon denied engaging Star Domain for a cleaning deal worth RM7.42 million.

In some cases, not too much effort was put into disguising the fraudulent information provided like in the RM2.27 million contract with OSK Trustees Bhd.

A fictitious company registration number “00000-X” was submitted, while OSK Trustees Bhd was bought over by RHB Trustees Bhd in 2013.

One of the companies, Maju Transport & Express Sdn Bhd, said to have contracted Star Domain Resources for cleaning services; however, it confirmed engaging Star Domain on May 15 but has since terminated the contract.

Its director Siow Fei Chu, however, declined to confirm if the contract was worth RM2.59 million, as claimed by Star Domain in its quota application.

Quotas for sale

Seal of the Inland Revenue Board of Malaysia on the said agreement between Star Domain and Monas University.

Quota fraud is a lucrative business in more ways than one.

According to industry insiders, Malaysian employers awarded quotas can sell them for as much as RM10,000 per head to middlepersons who later sell them to recruitment agents.

When a quota application is put in, the word is put out along the chain of agents, triggering a series of events, including a bidding war among agents to secure those quotas even before the application is approved, insiders told Malaysiakini.

It is learnt that in the cases which Malaysiakini investigated, middle persons paid deposits to the quota applicant for “letters of demand” which were then sold to recruitment agents in sending countries, even before the quota was approved.

This meant the number of letters of demand sold may exceed the number of workers alloted in the final approved quota, leaving many recruitment agents in a lurch when calling visas never get issued.

For example, Star Domain was awarded a quota of 980 workers but is alleged to have sold ‘letters of demand’ for more than 3,000 workers to recruitment agents in sending countries, according to documents sighted by Malaysiakini.

To convince the recruitment agents that the demand was real, the syndicate held job interviews with the prospective workers via Zoom, ordered cleaning services uniforms for them, and used a bespoke worker management IT system which the agents uploaded information into.

But insiders told Malaysiakini the agents and migrant workers were not the only ones duped.

The company’s Malaysian staff who conducted the interviews with migrant workers were also none-the-wiser that they were part of the con, believing they were part of a legitimate establishment.

Kicking the cost down to the worker

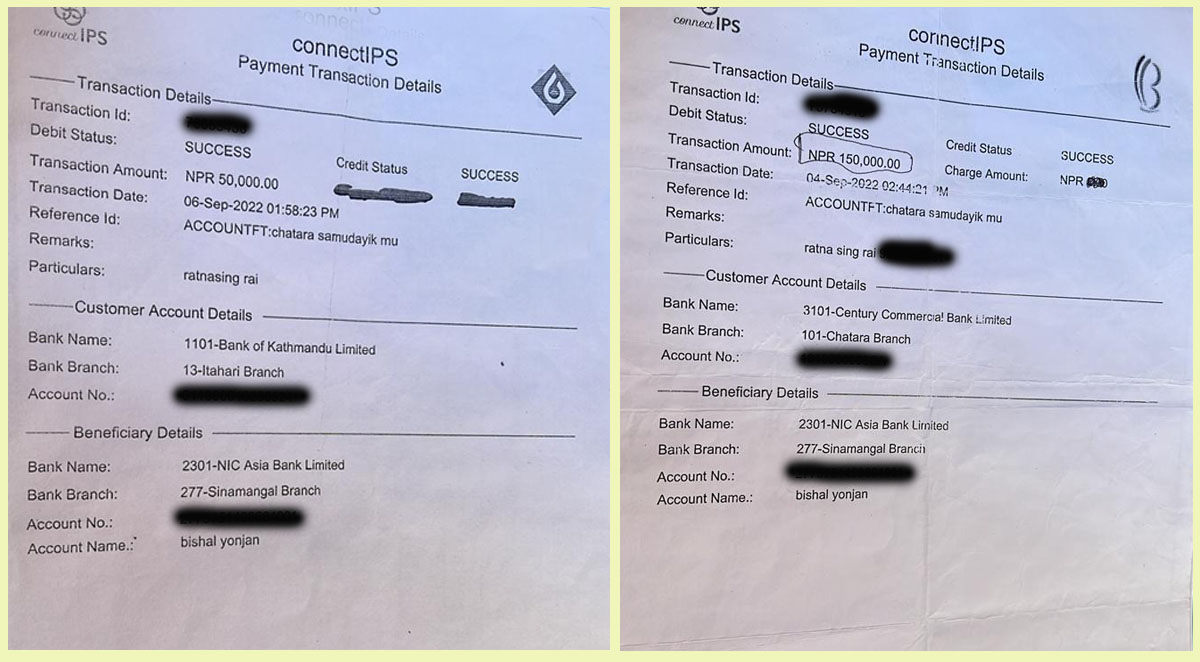

Agents in sending countries usually pay a fee to the middle persons, which they later recoup from the workers who pay a recruitment fee via brokers to secure the jobs in Malaysia.

To afford this, workers take multiple high-interest loans, believing they could recoup that from the high-paying positions promised to them. But those positions never existed.

If the agency agrees to buy the quota from an employer at RM10,000 per worker, the rate they charge workers will be twice that amount, plus an additional RM3,000 to compensate agents in the villages, industry sources told Malaysiakini.

The original quota bearers, however, are far removed from this flurry of economic activities they activate.

Their role involves receiving a one-off payment from the middle persons, often in a duffle bag full of cash, and finally, with the arrival of the workers. Then, the workers become cash cows that can be rented out to other companies like chattel.

Quota prices can also change according to country of origin as Bangladesh agents are able to extort more from their nationals, it is learnt.

Workers told Malaysiakini they are required to pay in cash and do not get receipts as proof of payment. If they raise questions, agents threaten to return their money and not arrange their passage.

Convinced of promises of potential high earnings in Malaysia, many desperate workers comply.

Cleaning services a convenient loophole

There is a reason why the fake foreign worker quotas were requested under cleaning services.

Stranded workers in Malaysia.

Labour outsourcing was outlawed in 2018, making it illegal for labour supply agencies to hire migrant workers under their name and deploy them to work elsewhere.

The construction sector is exempted from this rule but those found guilty of outsourcing in other sectors face hefty fines and, or imprisonment punishable under the Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Anti-Smuggling of Migrants Act 2007/22 and the Private Employment Agencies Act 1981 (Act 246).

In recent years, the cleaning services sector has offered a convenient loophole, making it the preferred camouflage for traffickers supplying workers under the guise of cleaning services.

Employers providing cleaning contracts are allowed to station their workers at a client’s premises as their cleaning staff for a contracted period.

But when they are at the client’s premises, they may also be tasked to do other jobs, like waiting tables or kitchen duties or joining the assembly line at factories, industry insiders told Malaysiakini.

This means once the workers are in Malaysia, they can be supplied to other companies without technically breaking the law.

Facing threats

From late January to March, a group of 166 workers arrived on a quota awarded to Aecor Innovation, one of the six companies in the syndicate. There were no jobs for them.

The workers in Malaysia sharing garlic and onion as dinner.

Twenty lucky ones were put to work as cleaners in February. The others started work in June.

Just as things started to look up, in July, they stopped receiving their salary. They got nothing until September, workers told Malaysiakini. By then, they heard Aecor had lost its cleaning contract.

By October, only 97 remained with the company.

When met, they said even when they were paid, there were major deductions from their salaries for things like lodging, phone SIM cards and ‘advances’ – against labour regulations and their employment contract.

Their contract promised free lodging but the workers were charged RM100 each and crammed into a room of 10.

Their payslips, sighted by Malaysiakini, did now show that social security payments (Socso) were made but that deductions were done for “demerits”.

“The slightest mistake is a demerit. I took my phone out of my pocket to look at the time, the supervisor took a photo and RM200 is demerited from my salary,” said one Bangladeshi worker, via a translator.

Workers’ wages were also deducted for “assistance” they received, when they were stranded and jobless, following the Human Resources Ministry’s interventions.

Apart from the RM500 they received in September as an advance, the workers were hungry and on the verge of tears for having to ask families to send them money just to survive.

The workers stopped work en masse at the end of September, even in the face of alleged threats from Aecor Innovation that their work visas would be cancelled and they would be sent home immediately, they told Malaysiakini.

On Oct 2, the workers lodged a police report against Aecor for alleging non-payment of wages and threats by the employer toward those who inquired about their months-overdue wages.

The workers claimed that the employer had even threatened to cancel their work visas and have them arrested and detained.

They also submitted a complaint to the Putrajaya Labour Department, pleading to be rescued from “hostage life”, seeking intervention to secure a new employer and demanding their back wages and reimbursement of recruitment fees of 450,000 to 500,000 Bangladeshi Taka (RM19,00 to RM21,000).

Despite their collective action, they remained anxious because being sent home before they could raise enough funds to repay their debts could have consequences as dire as death.

“If I have to return now, I will either murder my family and kill myself or be killed by those from whom I have borrowed,” said one worker.

“The only choice I have is how I will die.”

Malaysiakini sent questions to all the Malaysian companies mentioned in this report, seeking a response. None have replied at the time of publication.

The Immigration Department and Labour Department have also not responded to Malaysiakini’s queries.

This article was also published in Malaysiakini