Mukesh Pokhrel | CIJ, Nepal

Rejina Bishwokarma finished her hastily conducted SEE examinations just before Nepal enforced a nationwide lockdown aimed at preventing the spread of Covid-19. She has nothing to work at her residence in Kirtipur. In June 2020, she went to Machhapurche of Pokhara to meet her grandparents.

Rejina’s parents also joined the family in Pokhara village. On July 17, landslides buried their house and killed Rejina. “Daughter was planning to return to Kathmandu. But she never returned,” said her father, Hiralal.

Dozers constructing road clearing community forest in Kirtipur. All pics: Mukesh Pokhrel

Two of her uncle’s sons — Kushal BK (13) and Samir BK (14)—were also buried under the debris.

“Due to landslides a heap of mud that was piled up above my house in the course of constructing the road buried my house wherein my daughter and cousins died,” said Hiralal. The same landslides displaced Rabilal Bishwokarma, Dil Bahadur Bishwokarma and Khemraj Bishwokarma.

“We have fixed sewage to prevent possible landslides in the rainy season,” said Krishna Prasad Dawadi, chief of ward no. 1 adding, “A wall is constructed along the road side.”

Chitra Bahadur BK said he’s still staying in the landslide-prone area. “It’s okay in winter. But I often feel landslides will sweep away me someday in the rainy season,” said Chitra Bahadur.

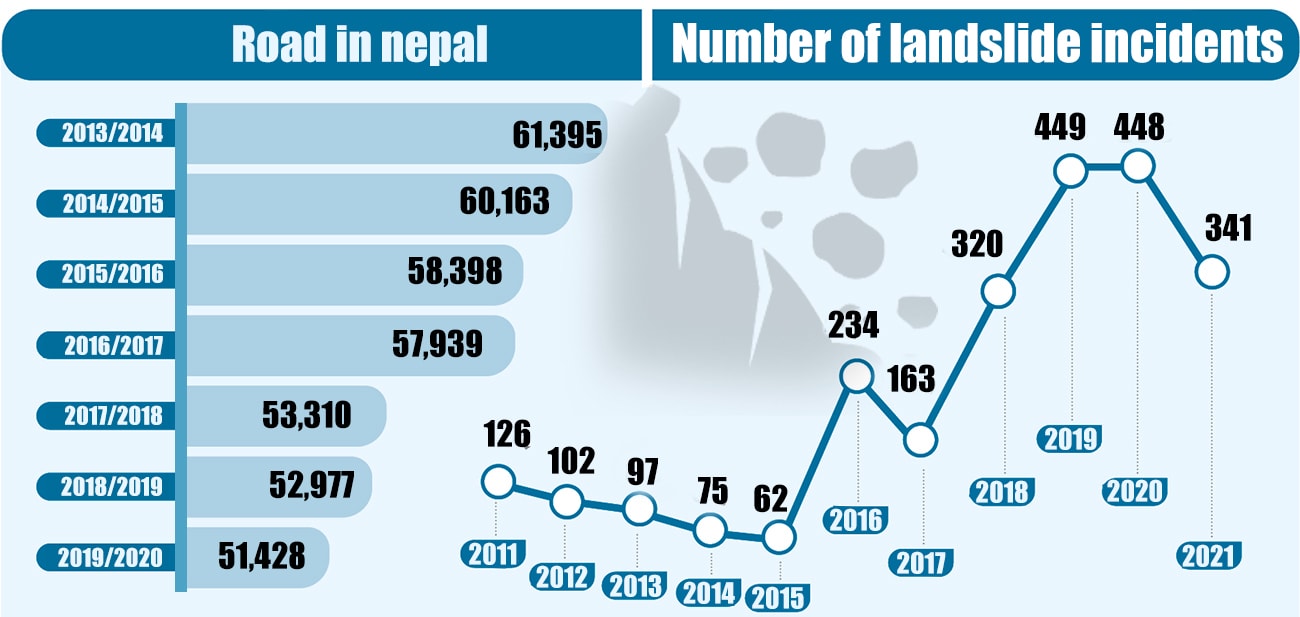

Between mid-April 2021 to February 25, 2022, 181 people have died in 341 landslides, according to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority. Additionally, 33 people are missing, 137 injured and 611 households affected in the landslides.

Anil Pokhrel, authority’s chief executive officer, said half of the total landslide cases happened because of road construction without environmental impact assessment. Pokhrel complains the local governments of overlooking possible impacts of haphazard road construction in the long-run.

Eight houses in Pokali of Likhu Rural Municipality, Okhaldhunga, were damaged because of a haphazardly constructed road. Village chief Sukbir Tamang said roads constructed in winter caused this devastation in the rainy season.

Also, 13 people died in landslides in the district of Parbat. Devi Pandey, chief district officer in the district, says 90 percent cases of landslides are linked to haphazardly road construction.

Political Economy of 2020 Landslides, Road Construction and Disaster Risk Reduction in Nepal, the research published by Oxford Policy Management, shows rural road construction as a major cause of landslides. Of the total 337 landslides cases reported in 35 surveyed districts, 61 percent cases were linked to unplanned road construction.

The research conducted based on the death toll of landslides occurred between 2011-2020 shows occurrence of landslides is increasing in recent years. In 2011, 126 cases of landslides were recorded whereas annual landslides cases reached 488 in 2020. The data shows cases of landslides are expanding across the country as road construction is happening in every corner of the country. (See infographics).

Forest cleared to construct road

Hiralal said locals had protested the road construction project when local authorities started constructing the road above his house. “We protested saying that constructing the road above the house will pose a risk to us,” he said, “But local leaders didn’t listen to our pleas and we lost our children.”

The government enforced nationwide lockdown to prevent the second wave of deadly covid-19. When people were confined indoors, Kirtipur municipality cleared forest areas and constructed a five kilometers road connecting Pushpalal Park to Champadevi. Tara Lal Shrestha, a local who teaches at the Tribhuvan University, says the wetland and trekking route was destroyed by using excavators in the name of road construction.

“Present day road was constructed in a wetland area which is very sensitive from environmental perspectives. By constructing roads, they damaged the natural beauty of the community.”

Like Kirtipur local authorities in Bakaiya of Makawanpur used excavators and cleared Chundevi community forest to construct roads. This all was done without environment impact assessment during the pandemic.

Similar approach was adopted in Alital and Navadurga rural municipalities of Dadeldhura district. Both the local governments cleared community forest. According to the Divisional Forest Office in Doti nine local governments have constructed roads without environment impact assessment and studies.

“We requested them in writing thrice and sent related forest laws,” said Laxmi Joshi, assistant forest officer adding, “But none of these local governments listened to us.”

Joshi admitted her office was unable to stop wrongdoings of local authorities despite seeing everything before their eyes.

Fifteen local governments from Annapurna Conservation Area constructed the road. None of them had carried out initial environment examination and environmental impact assessment.

“Local governments across the country have constructed the road haphazardly,” said Rajendra KC, deputy director general at the Department of Forest.

Since there’s no integrated record keeping system, the government has no details about road construction.

Narpa Bhumi rural municipality of Manang constructed more than 10-kilometer road by using the excavators. Rural Municipality’s chair Mingma Tshering Lama argued the development works can never happen if road construction is to follow due procedure.

“Development works can’t happen if we have to wait for IEE and EIA,” said Lama adding, “Environment impact assessment is essential only if cliffs and mountains are to be cleared. Why environmental impact assessment is essential to construct roads by removing soil.”

Landslides after the road was constructed in Kirtipur.

Chandra Ghale, chairperson of Naso rural municipality, said the municipality hasn’t carried out any environmental assessment before starting road construction so far.

Only a 20-kilometer road was constructed in the last four years. “If you listen to forest office development will never happen in Manang,” he said.

Narbhumi, Manang Disyang and Chame rural municipalities of Manang have also never carried out environmental impact assessment.

Raj Kumar Gurung, director at the Annapurna Conservation Area Project, said the project only is not responsible for enforcing environmental law. “It’s not our sole responsibility. It’s up to all three tiers of government as well. We have asked them to act.”

High-empowered local bodies are focused on development works rather than addressing genuine local needs. Federalism has ended the tradition of approaching Singha Durbar to demand development projects. But as local governments ignore the agenda of sustainable development goals, forests are cleared. This has caused floods and landslides like disasters. Haphazardly constructed roads are not in operation.

That’s what happened in Kirtipur. The Champadevi road constructed with an investment of Rs 5 million is damaged by the landslides. Vehicles aren’t playing anymore.

In Manang, roads destroyed by floods aren’t yet in operation. “We are repairing roads again by using excavators,” said Chandra Ghale, chief of Naso rural municipality.

All eyes on profits

Road network is considered as a basic development indicator. Road shortens distances, eases transportation and creates job opportunities. But it invites destruction if roads are constructed without environmental impacts in the future.

If reasons behind building roads without environmental impact assessments are analyzed, construction entrepreneurs are also dragged into this ongoing haphazard road construction.

According to the Federation of Contractors’ Association of Nepal, more than 300 elected people’s representatives were contractors. Of them, 69 are chief of local governments.

Needless to say, construction workers own construction equipment like dozers and excavators. And the same equipment was used to build roads, even clearing forest, according to divisional forest officers.

“Haphazard road construction is happening because of pressure from local government chiefs with contractor background and other contractors,” said Bishnu Prasad Acharya, forest officer at Rapti Divisional Forest Office, Makawanpur.

For example, Kamal Poudel, ward chief of Shitalganga Rural Municipality, Arghakhanchi, owns a dozer. The same dozer is used to construct roads. Hikmat Pokharel, chief of ward no. 10, is also a dozer owner.

In some places, political interest also plays a role. Ramesh Maharjan was fielded as mayoral candidate from the CPN-UML whereas Raj Kumar Nakarmi was Nepali Congress candidate. Shyam Kumar Adhikari of Nepali Congress also fielded him as an independent candidate.

Adhikari secured 892 votes. Adhikari, according to a NC leader who didn’t want to be quoted, was field rival candidate at behest of UML candidate Maharjan. To appease Mayor Maharjan named Adhikari as road construction users’ group chief.

This year, Kirtipur municipality has allocated Rs 10,000,000 to upgrade the road. Mayor Maharjan argued the budget was allotted as per local demand. The municipality hasn’t even informed the Divisional Forest Office before constructing the road.

“We considered it works if the community forest gives us the go ahead. So, permission was obtained from the community forest,” said Mayor Maharjan.

Krishna Prasad Dawadi, ward chief of Machhapuchhre-8, Kaski, said the road was constructed as per local demand but local government was blamed after landslide destruction. “Everybody wants a road to their courtyard,” he said, “Landslides occur in some places but locals exert pressure on us to construct roads.”

Bypassing law

Forest Act 2076 has a provision to seek approval from the National Investment Board in case of completing national pride projects and obtain environmental impact assessment for other development projects so that there will be no environmental hazards in the future.

Additionally, article 42 (3) of the act states if there is no other alternative to the using of forest area for the operation of any development project by the Province or Local levels and it appears from the environment ethe project can request the government for acquisition of the land in such forest area for the operation of that project.

But law hasn’t been adhered to anywhere. Environmentalists said haphazard road construction is taking place as elected people’s representatives aren’t fully aware about environmental impact assessment.

A newly constructed road in Bagmati rural municipality. Forest was destroyed to build this road.

“Most of the workforce working for the local government don’t understand environmental assessment. So, they are haphazardly using excavators as if forest is their private property,” said Sanot Adhikari, an environmentalist, “Local officials must be trained so that they could understand impacts of haphazard road construction. Mere blaming doesn’t make sense.”

Divisional forest officers admit their failure to act against elected people’s representatives and stop haphazard road construction. They feel threatened to go against politicians.

So far, the divisional forest office has a field just in case. Makwanpur Divisional Forest Office has filed a case against Damodar Khanal, chief of Bakaiya Rural Municipality, chief executive officer Laxman Pudasaini and users’ group head Sirjana Thing.

Responding to the case, the district office slapped a fine of Rs 100,000 for rural municipality chief and Rs 50,000 chief executive officer.

Forest officers rarely move to the court against the political leadership. Bishnu Prasad Acharya, the then divisional forest officer of Dadeldhura, says he had to face enormous political pressure when he attempted to start a legal fight against destroying forest to build roads.

Kathmandu divisional forest office also failed to take action against local officials for destroying forest. A group of forest activists had filed a complaint against Kirtipur mayor Maharjan, deputy mayor Sarswati Khadka and chief executive officer Krishna Prasad Sapkota at the commission for investigation of abuse of authority. But the forest office hasn’t dared to take action against the accused for destroying the forest.

Asked about the delay in taking action for destroying the forest a forest official said no action was taken against the accused. “Rather we have suspended the bank account of the community,” he said.