Those unable to afford private healthcare have no option but to wait for the seemingly never-ending queue at Tribhuwan University Teaching Hospital and Bir Hospital.

Shivahari Ghimire: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Narjit Shahi, 43, from Bajura District’s Jagannath Rural Municipality-5, brought his wife and five children to Kathmandu when he was offered work at a cow farm at Suntakhan in Gokarna, in the outskirts of Kathmandu city. At home, he had been unable to make ends meet no matter how hard he worked. So had packed up for the capital city when his friend had said life would be easier here.

Shahi and his family got a place to stay at Suntakhan, in a hut next to the cow farm. The Shahi couple began work at the farm; their children also supported them. They received Rs20,000 a month as salary apart from food and lodging. The family put all their energy to work as if it was their own farm.

One day, in the second week of February 2020, Shahi began complaining of back pain. When the pain became severe, he visited the Tribhuwan University Teaching Hospital at Maharajgunj. The hospital diagnosed a problem with his veins, and asked him to come back in April. Shahi stayed home for a few days, and when the pain got worse, he visited the Kathmandu Medical College at Sinamangal in the first week of March 2020.

The hospital said his treatment would cost Rs3 lakh, which was too huge an amount for Shahi to be able to gather. He returned from the hospital and reached the National Trauma centre in the first week of Chaitra. The hospital did not admit him. He would have to cough up Rs2 lakh for the treatment, he was told.

Shahi had no option but to return to Suntakhan. He had spent Rs50,000 by then. “Maybe that amount would have been enough to get a treatment at a government hospital. I ended up spending so much running here and there,” Shahi said.

Shahi had no option but to return to Suntakhan. He had spent Rs50,000 by then. “Maybe that amount would have been enough to get a treatment at a government hospital. I ended up spending so much running here and there,” Shahi said.

Shahi’s lower body became paralysed in April 2020. His family started to have a hand-to-mouth problem once money stopped coming in. To add insult to injury, the farm owner asked the family to leave the farm.

The family now lives in a hut in Gokarna and is dependent on the generosity of other people.

“When he was well, he looked after the family. Now we have to look after him. How are we to survive?” said Shahi’s wife Dhauli Devi.

“I had thought Kathmandu was a city of educated people and basic amenities. But it turned out to be a sad and cruel place for poor people like us,” said Shahi, who still hopes to receive treatment with the help of generous people and public healthcare.

Two-year waitlist

Rita KC, 29, from Magdi, visited the TUTH to undergo surgery for pancreatic stone. She had been referred from a hospital in Myagdi district after the diagnosis. However, despite suffering from acute pain induced by the stone, she was given an appointment for a date two years away.

KC, who is unable to pay for her operation at a private hospital, has been waiting for her turn. But she is not sure whether she will be able to undergo an operation as the coronavirus pandemic drags on.

“It’s quite difficult. I don’t know how long I will survive as I depend on the (government) hospital. I had gone to the hospital when I had an emergency during the lockown, but the doctors sent me back saying they were not conducting operations,” KC said.

Like Shahi and KC, Shubhadra Gajurel from Kathmandu’s Budhanilkantha area is also awaiting her turn to undergo a surgery even as she suffers from kidney stone.

When she reached the TUTH for medication in January 2020, she waited at the E-3 section of the Out-Patient Department. Her husband, Suman Gajurel, was accompanying her. Three days earlier, the doctor advised her to undergo operation for renal stone and had invited her to the hospital to take an appointment for operation.

The doctor gave her an appointment for February 2021. Shubhadra’s husband was surprised to see a two-year waitlist for his wife, who was having acute pain. When he requested Dr Ganeshwar Shrestha for an earlier date, he was rebuked. “Go somewhere else if you need an earlier date,” said the doctor.

Suman decided to take his wife to a private hospital even if he had to borrow money. But he was discouraged upon hearing that the expenses at a private hospital would easily cross Rs1.5 lakh. Shubhadra still awaits her surgery date at the TUTH.

Parvati Shrestha, 37, from Lajimpat in Kathmandu, also awaits her surgery date for pancreatic stone in June 2021. Her family is unable to take her to a hospital, and worries whether Parvati will be able to make it to the day of the surgery.

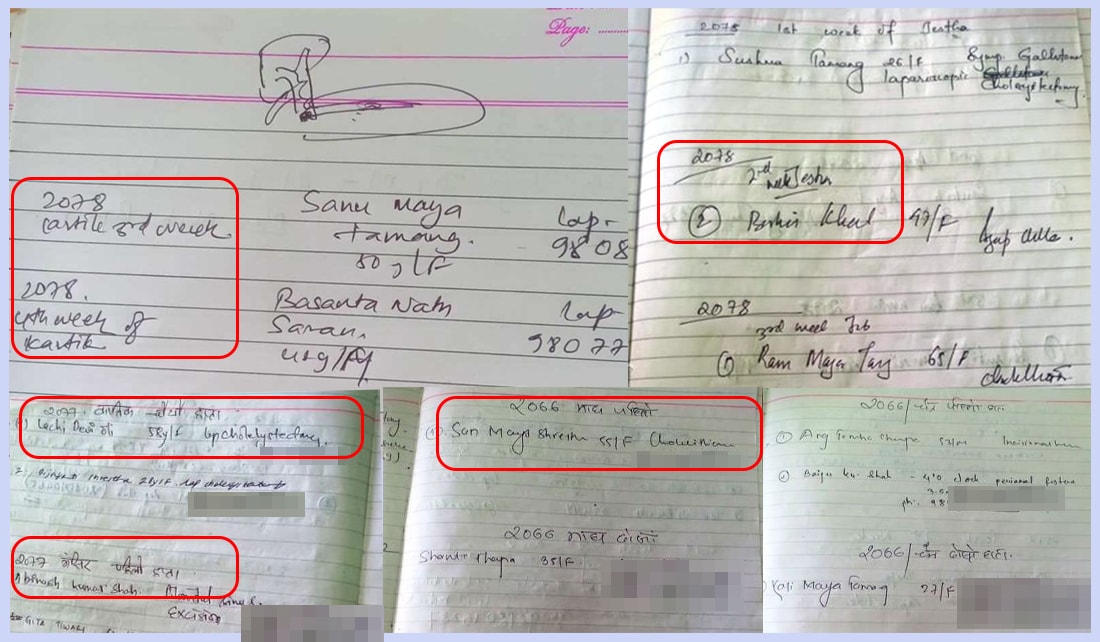

Basanta Nath Sharan, 40, from Rajbiraj in Saptari, suffers from paralysis. He was also diagnosed with a 10-mm pancreatic stone. The doctors at the TUTH advised removal of the stone as soon as possible, but he has got a surgery appointment only for the last week of November 2021. Unable to find resources for surgery at a private hospital, the family took Basanta back to Rajbiraj. The hospitals in Rajbiraj even refused to admit Basanta as he was suffering from two ailments, Basanta’s sister Prinsha Sharan told CIJ Nepal.

Kamala Kumari Yogi from Kohalpur in Banke, Malati Kumal from Lamahi in Dang, and Shanta Thapa from Hinguwa in Panchthar also continue to suffer as they await their surgery dates for removing pancreatic stone.

“We can’t afford private healthcare”

Sanumaya Tamang, a resident of Kholegaun in Shivapuri Rural Municipality in Nuwakot, visited the Bir Hospital in December 2019. After an ultrasound test, she was diagnosed with a 13 mm kidney stone. The stone would have to be removed through a surgery, but she got an appointment for a year later.

She visited the TUTH in February 2020 because she did not want to stay with the disease. The doctors, upon examination, gave her an appointment for November 2021.

“When I realized that it was impossible to get a timely treatment at both the government facilities, I went to a private hospital for a surgery. I spent around 1.3 lakh for the surgery,” Tamang said.

Shobha Bartaula, 70, a resident of Aldomar in Makwanpur, visited the TUTH in December 2019 after she felt acute pain due to pancreatic stone. She had no option but to undergo a surgery. But she got an appointment for December 2020.

Prior to that, she had been admitted at the Om Hospital at Chabahil for a month. But the hospital did not conduct the surgery claiming she was at high risk due to her old age. Her husband, Sitaram Bartala, took her to the TUTH. But the hospital gave her a surgery appointment for a year later. Shobha now awaits her appointment date for surgery.

Another pancreatic patient, Kalimaya Tamang, 28, from Naubise, Dhadhing, faced a similar problem when she visited the TUTH. She was told that she would not get an appointment for a surgery before April 2021. “We’ll ask the doctor once again. And if we are not going to get an earlier date, we’ll have no option but to take loans for treatment at a private hospital,” said Mamba Chyang, Kalimaya’s husband.

“We can’t handle all patients”

In big government hospitals such as TUTH and Bir Hospital, patients except those suffering from serious problems do not get an appointment for surgery. Patients usually have to wait for up to two years before they get an appointment for surgery for ailments such as kidney or pancreatic stone.

The patient cards of patients awaiting surgery appointments for as late as November 2021.

According to Dr Santosh KC of the TUTH, this is because of the high volume of patients the government hospitals receive. “Bir Hospital and TUTH receive patients from all over the country. These two hospitals can’t handle so many patients. There should be additional infrastructures to deal with this issue,” KC said.

The coronavirus pandemic has worsened the problem, making it impossible for the hospitals to conduct surgeries. As a result, patients are compelled to visit expensive private hospitals for treatment.

After the lockdown began, the big government hospitals based in Kathmandu have stopped admitting new patients claiming they are not able to conduct surgeries. TUTH has a list of 540 patients waiting for surgery until April 2078. Bir Hospital’s waitlist has 247 patients.

According to Ram Bikram Adhikari, public information officer at the TUTH, hundreds of patients who were waiting for surgery failed to turn up during the lockdown.

Professor Dr Paleshwa Joshi Lakhe, head of the Gastrointestinal and General Surgery Department at TUTH, said the department conducted surgery on five stone patients per day. The department has seven surgeons. She said the limited human resource at the department was unable to handle the large number of patients who come from all over the country. “Patients with severe ailments do not need to wait. But it is not possible to conduct surgeries on all patients who come here. So we advise them to go elsewhere for less severe cases,” Lakhey said.

According to TUTH authorities, the hospital has conducted 2,051 surgeries since July 2019. The hospital usually conducts an average of 50 surgeries per week. In normal conditions, TUTH has five departments that conduct surgery. They include GI and General Surgery, Neurosurgery, Urosurgery, Plastic Surgery and Pediatric Surgery. These departments conduct surgeries on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. But the departments have not been able to conduct appointed surgeries these days. Dr Ganeshwor Shrestha said these departments are not able to handle the patients in normal conditions as the volume is excessively high. “Most patients visit the government hospitals for easy treatment. But the resources here are not able to handle that. That is why many patients are kept on the waitlist.”

However, the waitlist does not apply for everyone. Those with access do not need to wait for treatment. Patients coming from far-fetched areas complain that they have had to wait for years to get treatment whereas those from access get immediate service. Mahesh Shah, a visitor at the hospital, said, “Those who came later than us have already returned home after getting treatment. But we have been given an appointment for next year.”

Radha Timsina, a resident of Kharipati in Bhaktapur who awaits her surgery date at the TUTH, said patients like her who do not have access are made to wait in queue whereas those with access get preferential treatment. The hospital had given her an appointment for April 2020 earlier but refused to conduct the surgery on the appointed date due to the pandemic. “If I had been related to the officials at the hospital, I would have got the treatment much earlier. But when I call the hospital, they just ask me to wait,” Timsina said.

Madhav Ghimire, acting in-charge of the hospital administration, conceded that the hospital gave preferential treatment to some patients over others on the basis of their access. “Those familiar to the staff try to overstep others. Several patients take the appointment for surgery by contacting the doctors themselves. This puts those waiting in the queue at a disadvantage.”

The suffering of the patients who have been awaiting delayed surgery appointments shows that the promises made by political parties during the elections were just for public consumption. The ruling Nepal Communist Party (the then Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist-Leninist) and Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) had said in its electoral manifesto: “We would ensure a considerable increment in investment in the health sector.” The manifesto further said, “All citizens will be brought under compulsory health insurance, the government would pay 50 percent of the health insurance of citizens who are under the poverty line, and each rural municipality and municipality will have 25 and 50 bed hospitals each respectively.” But the fact that citizens in Capital city have to be on long waiting lists for getting treatment raises questions on the validity of the public pronouncements that political parties make in a democratic system.