Fraud is rampant in Nepal’s internet service. It is committed in two ways: by not delivering even a fourth of the agreed data speed, and not restoring service immediately after disruption. While this has been going on for quite sometime, the regulator Nepal Telecommunication Authority hesitates to punish service providers.

Saraswati Dhakal: Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Six months ago, Worldlink representatives visited the home of journalist Lenin Banjade to demonstrate their NetTV product. The salespeople said that besides television, subscribers could also watch Film Gallery and YouTube on it. Banjade bought an annual subscription of the internet service provider for Rs 18,700. But after three days, NetTV and YouTube were cut off. When Banjade called up the company, he received a reply that YouTube would not run for technical reasons.

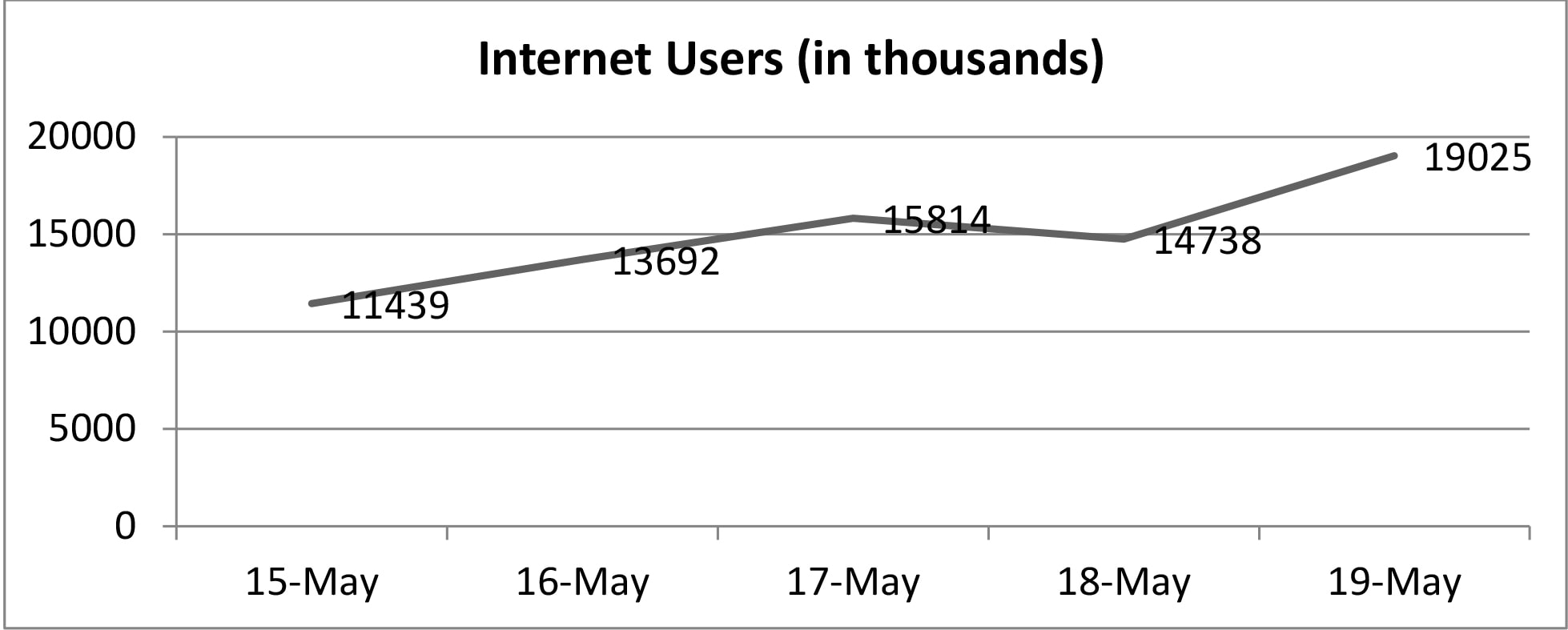

Source: Nepal Telecommunication Authority

Banjade filed a complaint against Worldlink at the Nepal Telecommunication Authority saying that the service had been disrupted without prior information. Banjade, who demanded action for the company not providing the agreed services and compensation, had not received a response from the authority until the third week of January.

Manju Thapaliya of Chundevi in Suryabinayak Municipality-6 uses internet as her pastime. Manju subscribed to “25 megabits per second” of Worldlink internet annual scheme for Rs 16,000. According to the four-year-long Worldlink customer, the service was good in the first 18 months. Now videos do not play well. While the internet runs slow during the day, it gets a bit faster after 11 at night. “It doesn’t get repaired even after repeated phone calls. It buffers while watching movies online,” she said, adding that streaming is slow even with the claimed 25 mbps bandwidth.

Dr Rajiv Subba, former chief of the communication directorate of Nepal Police, has been using Subisu internet for the last four years. In the past one year, he has also been a Vianet internet customer. Subba says he switched to another service as he was not happy with the speed of Subisu internet.

There have been improvements in internet services lately but, Subba believes, Nepali internet service providers (ISPs) have not been able to bring them to customers. “Twenty-five years ago, the Mercantile service was quite expensive. Today, pretty fast internet is available for two-three thousand rupees per month. Since the ISPs use the sharing mechanism, problems arise when one customer needs fast speed,” Subba says.

According to the Nepal police official, the common problem of Nepal’s ISPs is their failure to deliver the promised speed of internet. “ISPs study the pattern. For instance, no one uses internet at my house during the day. At that time, they divert the speed to another subscriber. When I’m home on leave some days, I find the problem in internet,” says Subba.

Biplav Man Singh, former chairman of the Computer Association of Nepal (CAN), sees a gradual improvement in the internet business in Nepal but finds no reason to be satisfied with the services. “Companies don’t meet the commitments they made to customers. While companies show 10 mbps internet, they don’t deliver even 128 kbps. The transfer rate is also not as claimed. Service is not dedicated and downlink is problematic,” says Singh.

“Most of the ISP owners are my friends. But what use is that? You can’t call up the owners when there’s a problem,” Singh says. “Companies advertise their products citing ‘mb’s. But consumers can’t be certain in the lack of speed meter even when they know they are being cheated.” Singh, who is informed in the information technology, is aware that he has been short-changed but does not care to file a complaint as the regulator is not serious.

Bidyut Lamichhane, who studies MSc at Patan Multiple Campus, has been using Subisu internet for the past three years. He pays the ISP Rs 1,308 per month for the promised 15 mbps internet. “Now I don’t believe I get even 1 mbps speed,” he says.

The internet connected to the house of Lamichhane, an active social media user, at Raniban Dhungedhara has connection issues generally three times a month. “When I call them up, I get response that it will be fixed but it takes nearly a week for the service to resume,” he says.

According to Lamichhane, problems with Subisu internet are not delivering the claimed speed and lack of prompt maintenance. Out of compulsion, he also uses mobile data now. “I tag Subisu on Twitter to register my problem but it is not addressed.”

Rejina Acharya, communication officer at Subisu Cablenet Private Limited, does not agree. She says at times problems arise due to customers themselves. Internet service is disrupted when the router is not placed at the right place, power is not well connected, and when network cable is severed or gets loose, she argues. “Our support team reaches the spot the moment a problem is diagnosed. You can’t compete without quality and timely services,” Acharya says.

Mahendra Man Gurung, chief commissioner at the National Information Commission, is a former secretary at the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology. He also chaired the Nepal Telecommunication Company (Telecom) earlier. At home, he uses the ADSL service of Nepal Telecom but he is not satisfied with the service. He prefers the latest internet technology of Fiber to the Home.

Gurung says the Nepal Telecommunication Authority had prepared the working procedure to address the issue of substandard service through compensation. “Its implementation addresses several problems related to poor quality services since the company compromising on quality has to provide compensation to customer,” says Gurung. Nepal Telecom Managing Director Dilliram Adhikari says, “We have set up a separate unit to address customers’ problems. There are no complaints now as in the past.”

Megabytes and megabits

Despite the claim of service providers, cases of consumers being cheated are growing with increased access to the internet in Nepal. Amid a growing demand and a limited number of ISPs, people are not getting the services they paid for. The cost is high for low-quality internet services. Dr Awish Adhikari, oncologist at Kathmandu Cancer Hospital, says ISPs have been cheating consumers by openly advertising their schemes. “The regulator gets the information from various mediums of consumers being cheated but I wonder why it pays no attention,” he said.

What general conversation with internet users shows is – subscribers paying between Rs 1,000 to Rs 3,500 do not get internet connected to their homes for three to four days each month. ISPs that attract people with advertisements of minimum 8 mbps up to 35 mbps speeds do not deliver even a fourth of the speed.

What general conversation with internet users shows is – subscribers paying between Rs 1,000 to Rs 3,500 do not get internet connected to their homes for three to four days each month. ISPs that attract people with advertisements of minimum 8 mbps up to 35 mbps speeds do not deliver even a fourth of the speed.

In the Nepali market, ISPs such as Worlklink, ClassicTech, Vianet, Subisu, Himalayan Online and WebSurfer and telecom service providers Ncell, Smart Telecom and the state owned Nepal Telecom cater to most internet subscribers. Most of the users’ complaints are about the service provider not delivering the agreed speed and having to call up repeatedly when there are disruptions in service.

In the market, companies are competing to lure customers with large mbps offers. Cheating begins right here. Even when prospective buyers are told mbps is megabyte per second, megabyte and megabit are hard to distinguish. Mbps is eight times smaller than MBps. Internet service providers sell megabytes but deliver megabits.

The internet speed companies deliver is megabits. The speed shown while downloading files is megabytes, according to blogger Akar Anil. When a server outside the country is used, data transfer is slower than while using a server set up inside the country. He advises that one can find out about the internet speed by checking with www.fast.com.

It is not that the regulator is not informed about consumers being cheated in the internet business. Anup Nepal, chief of the frequency department at the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, says: “Inside Singha Durbar, the system breaks down 5 to 7 times per month. ISPs present the pretenses of cables severed, a fallen pole or server malfunctioning time to time.”

Within Singha Durbar, the internet flows through the National Information Technology Centre, which receives the bandwidth from Nepal Telecom. Still, services are disrupted repeatedly. “As the chair and computer are ready when one arrives at office, the internet service has to be similarly accessible,” says Nepal.

“Since this is a technical issue, ordinary people have no information about it. The Telecommunication Authority has to make common people aware in accessible terms of one’s bandwidth and ways to measure it,” Nepal says. “If necessary, even public service commercials have to be run through media, but that has not happened yet.”

Manohar Bhattarai, former chief and information technology expert at the dissolved High-level Information Technology Communication, observes that the telecommunication authority has not been doing the mandatory inspection and monitoring to see if consumers are getting the agreed services or not. “The government has brought forth the concept of Digital Nepal. How can Nepal be digital when internet itself is problematic,” Bhattarai says.

The IT expert says consumers should get the bandwidth that the company promised while selling the package. If the service may be disrupted due to the sharing of bandwidth, it has to let the consumers know about it beforehand. The main problem now is shared internet. How it creates problem is—the number of users grows while the network is not proportionately widened.

Binay Bohara, proprietor of Vianet Communication Pvt Ltd and former chairman of the Internet Service Providers’ Association Nepal (ISPAN), disagrees. “The internet runs smoothly 23 hours and a half, but if it gets slow or is disrupted for half an hour we are cursed for the day,” he says. On the question of if consumers have been shortchanged due to the high sharing ratio, he says: “It’s just like the way. When it’s empty, one can use the whole but when it gets packed, people need to walk together.”

According to a management information system (MIS) report of the Nepal Telecommunication Authority, there are 20.7 million internet users in Nepal. The service providers are Nepal Telecom, Ncell, Smart Cell and the ISPs. Cable fixed broadband, wireless fixed broadband, WiFi, WiMAX, 3G, 4G and e-video are the mediums of transmission.

Possibly due to the increased connection of internet with day-to-day affairs of the Nepali society, internet service has now been a matter of public discussion. In the general elections of 2017, Smart City, free WiFi and affordable internet became the campaign agenda in urban areas. While public concern is growing, the laxity of the regulatory agency is frustrating.

Validation of maintenance charge

According to the Telecommunication Act-1997, no charges are levied on consumers for maintenance of internet. According to Rule 15 (h) of the Telecommunication Regulations, a service provider has to repair a telecoms service to the prescribed standard without charging consumers extra. However, a Cabinet meeting in July 2019 amended the regulations, allowing an ISP to charge maintenance fee.

As a result, service providers have started charging more than 50 per cent of the fee under monitoring, support, maintenance and networking headings. Officials at the regulatory authority say this is cheating customers. Yet, there has been no action against them. According to Anup Nepal, chief of the frequency division of the information technology ministry, charging for maintenance is wrong according to the global standards, which is happening in Nepal.

As a result, service providers have started charging more than 50 per cent of the fee under monitoring, support, maintenance and networking headings. Officials at the regulatory authority say this is cheating customers. Yet, there has been no action against them. According to Anup Nepal, chief of the frequency division of the information technology ministry, charging for maintenance is wrong according to the global standards, which is happening in Nepal.

The Telecommunication Regulations-1997 prescribes minimum standards for the service providers. According to Chapter 5 Clause 15 (a) and (b) the regulations, the tools and equipment used by the companies to provide their services have to meet the standards prescribed by the telecoms authority. Apart from this, the telecommunication service also has to meet the minimum standards specified by the authority time to time.

According to Index 1 Section c related to Bylaw 3 Sub-bylaw 1 of the Bylaws Regarding Telecom Service Quality-2017, a service provider has to ensure 80 per cent download and up to 75 per cent upload of the agreed internet speed. The way to measure this has also been specified, which is: a percentage of the ratio between the number of efforts made to access data and successful deliveries within a month.

Users can thus work out the ratio of their efforts of download and upload and successful results within a month. When an ISP fails to deliver on its promises, they can file a complaint. If 8 of the 10 attempted downloads do not complete on time, or 7.5 uploads out of 10 attempts, complaints may be filed.

Chapter 7 of the Telecommunication Regulations deals with disputes over telecommunication and their remedies. According to it, the party suffering from any dispute between a licensed company and a subscriber can file a specific complaint with the regulator.

Complaints galore

Most of the issues of users lured by the several schemes or services of ISPs concern the irresponsible replies of company staff to their complaints of internet disruption. Even if users have purchased 24-hour packages, connection is severed for 1 to 2 days or sometimes even 6 to 7 days. Nepal, the frequency division chief at the ministry, shares his experience: “In the promotional phase, services go well but when the commercial term begins, they fall back to the usual speed.”

The law requires a serving company to compensate for the days of service disruption at the end of package year. But no company keeps such records and consumers don’t claim compensation with an account of service breaches either. Even if someone approaches with a claim, ISPs shrug off their responsibility saying they have no such practice.

The law requires a serving company to compensate for the days of service disruption at the end of package year. But no company keeps such records and consumers don’t claim compensation with an account of service breaches either. Even if someone approaches with a claim, ISPs shrug off their responsibility saying they have no such practice.

Dinesh Adhikari, an auto parts trader in Koteshwor, Sahayoginagar, who uses Worldlink internet, says: “When my internet was disconnected three months ago, I called up the company but my problem was not addressed. I searched for the contact of the regulating authority and called up to report my problem. I was told to be physically present to file a complaint for the process to begin.” He realized that there was no system for online complaints even with the regulator of the rapidly advancing information technology. “Frustrated, I did not proceed with my complaint. Four days later, the service resumed,” said Adhikari.

Institutional consumers incur losses worth millions of rupees when service is disrupted. Even 10 minutes of service disruption cause huge losses for an IT company, bank, cyber café or a busy public service provider. Their reputation is questioned.

According to Mega Bank Chief Executive Officer Anupama Khunjeli, no banking activity is executed without internet. A bank manager visiting the central office for a meeting is no more practical. “Disruption in internet connection means a slowdown in service delivery. While city branches do not face serious disruptions, those in rural municipalities have serious connectivity problems,” says Khunjeli.

According to users, the common problems cited by internet companies are a fallen utility pole or system failure caused by power cuts resulting from transformer fires. These are not regular problems. Some company staffs are found to have given unhelpful responses like ‘reboot the router’, ‘the vehicle has run out of fuel’, ‘it’s raining’ or ‘it’s cloudy’.

There is, seemingly, competition in the telecoms sector but consumers do not get even the same product at the same price. When a company charges Rs 1,000 monthly for 20 mbps internet, another company may be offering it for Rs 750. When asked, consumers are told that prices differ based on the provider’s reputation. The Broadband Policy aimed at slashing the beginning broadband price to 5 per cent of the country’s per capita income. According to this, the starting price for broadband internet should have been Rs 5747.5 per year, that is Rs 478 per month. But people are forced to pay a minimum of Rs 1,000 per month.

The Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Policy introduced in 2015 has set a goal of making internet accessible to all. The government having set the goal of making broadband internet accessible to all Nepalis within 2020 imposed a 13 per cent telecommunication service charge in its budget for the fiscal year 2019-20. When the ISPs protested the move, the government validated the maintenance charge.

Min Prasad Aryal, spokesperson for the Nepal Telecommunication Authority, says: “If consumers complain about internet sharing, our team takes action after monitoring. Most importantly, consumers should be aware. Even if service seekers know whether the service provider has implemented its agreement or not, companies cannot cheat.”

A plain reading of Aryal’s statement is there is no hope of the regulatory agency taking action against service providers immediately despite the loot.