As the government fails in protecting people’s properties and returning embezzled money, billions of rupees deposited by hundreds of thousands of Nepalis at cooperatives remains at risk.

Ramesh Kumar |CIJ, Nepal

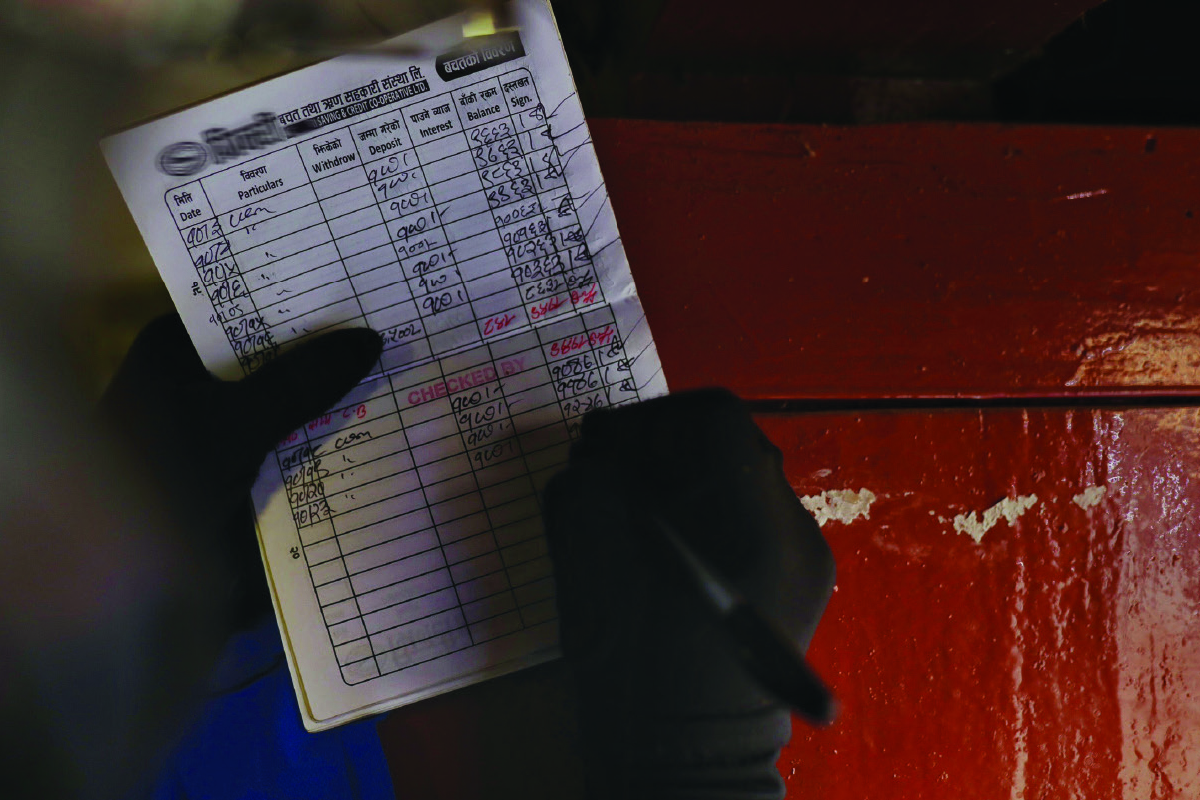

On January 2, Seeta Adhikari, an elderly woman, was sitting at the chautari—resting spot—in Narayan Chaur, Naxal, ruminating about the Rs200,000 that she had deposited at the Oriental Cooperative. She had saved the money to see through her old age but now the whereabouts of that money is unknown. The cooperative already shut down a decade back. “I’m thinking I will die without getting that money back,” she said.

Bishnubhagat Shrestha, a multi-disabled person from Bhaktapur, Duwakot, who did not get back the money he saved in Oriental Cooperative

Adhikari, who is originally from Kharanitar in Nuwakot, spent her life alone and without any support. She was married off in 1951 when she was all of 11. Her husband died three years later. Then began her painful life. In 1959, she came to Kathmandu, leaving behind her household and maternal home, and began working as a domestic help. Now she lives at a house in Naxal, the same home she works in.

She had received Rs100,000 as part of her husband’s paternal property. She had added Rs100,000 that she had saved over the years and deposited the total amount at Nepal Bank Limited. After a kith told her that the Oriental would provide her a better interest rate, she deposited her money there. When she learned that it was her life’s poorest decision, it was already too late. When she needed money to treat her illnesses, she reached one of the cooperative’s branches. But the office was locked up. Her decade since was spent trying to get that money back. “That money was all that I got, something I thought would be helpful in my old age,” she said. “The crooks took that away from me.”

There are thousands of Nepalis like Adhikari who deposited their money at the Oriental Cooperative, operated by Sudheer Basnet, and have had it embezzled.

According to the office of embattled cooperatives management committee, at Oriental, about Rs1.5 billion deposited by about 4,250 people remains bogged down for a decade. Khagendra Kafle, chair of the victims’ committee, says that the depositors have been struggling financially and have spent their time visiting government offices and courts. Kafle adds that there are innumerable stories of hardship the victims have suffered following Basnet’s “deliberate loot”. These are stories of family crises and financial struggles, he says. About a dozen such victims have already died.

Chhetra Kumari Dhanchhawa, a native of Duwakot in Bhaktapur who had deposited Rs2.6 million at Basnet’s cooperative, died early in 2021. She was 83. In 2011, she had deposited the money received as part of family property to take care of her son Bishnubhagat who can’t speak or walk. Chhetrakumari was living at her dilapidated maternal home in Duwakot. Speaking to CIJ in 2013, she had said, “If I get my money back, I could happily die after hiring a caretaker for my son.” But that was not to be. Bishnubhagat, who has no one in his immediate family, is currently taking shelter at his niece Sharandevi’s home in Gokarna, Kathmandu.

“My grandmother died while waiting to get her money back,” Sharandevi says. “If we got her money back, we could pay the loan taken to perform her funeral rites and would be of help to take care of my maternal uncle.”

Financial crisis

At noon on January 27, the office of Devendra Prasad Pokharel, chief of Kathmandu Metropolitan City’s cooperative department, was crowded with victims of cooperative fraud. Pokharel would ask them to file their complaints and counsel them about further procedure. Pokharel says that he meets dozens of such victims daily. “Some victims have warned they would self-immolate at the department’s office if they don’t get their money back,” says Pokharel, who is set to retire in a few months. “The situation is such that I feel like quitting my job right now.”

After the department receives complaints, it calls cooperative operators within a week for discussion. If the operators pay back the money within a certain period of time, the case gets closed; if not, the department sends a letter to the police for further probe.

Sunita Devi at the cooperative department to file a complaint after the cooperative where she had saved money was closed. Photo: Ramesh kumar

“So far, we have already sent 2800 complaints against 56 cooperatives to the police,” Pokharel said. According to him, in Kathmandu metropolis, of the 1600 financial institutions, complaints have been filed against 125. But the number could be more than that, Pokharel says.

Also on January 13, Bhawani Shahi from Naradevi and her husband were spotted with sad mein at the office of the department’s section officer Shivaji Bhattarai. Bhattarai was confessing to them that he couldn’t do anything to bring their money back and was suggesting they file a police complaint. Shahi said that she would come visit Bhattarai next week. “At least you listen to our troubles and we feel relieved,” she told Bhattarai.

One Adharbhut Cooperative in Indrachowk has refused to provide them over Rs3.4 million sum out of the couple’s fixed deposit of Rs7.65 million. On September 18, the department had brought together the couple and the cooperative’s manager Sabina Wagle and had made an agreement between them where the cooperative would pay the couple Rs1 million at the end of each month and clear all their dues within six months. But the agreement was not followed. Even though the couple received Rs3 million within three months, the cooperative hasn’t provided them the rest of the amount.

Bhawani’s husband, Bishwa, a butcher, says, “We are struggling to make ends meet. Now we are compelled to visit government offices leaving behind our work.” Wagle, the cooperative’s manager, says that because there’s a liquidity crisis in the market—that is, there’s a lack of money to invest in the market—the cooperative couldn’t return the couple’s money back. “The due date to return their fixed deposit is still not over,” Wagle said. “We will gradually clear it all.”

The fate of Oriental Cooperative a decade back seems to have engulfed many cooperatives around the country now. Dozens of such cooperatives have had complaints filed against them. Those that returned the depositors’ money are doing so on installments.

Binda Budhathoki, who runs a retail shop in Balkot, Bhaktapur, has Rs40,000 yet to receive from the Nagarik Bikas Cooperative, which has said that it could only provide Rs5,000 per month. On February 1, when the CIJ reached the cooperative’s office, its officials were asking depositors to visit a month later because the cooperative didn’t have any money left. A week later, the Minbhawan-based Kantipur Cooperative was asking the same of its clients.

A small-time trader has a daily routine of visiting Kuleshwar’s Garud Cooperative, where he’s deposited his money. The man, who says he faced hardship in foreign employment, deposited Rs730,000 at the cooperative but has only got Rs107,000 so far. “I need money to treat my daughter and to add goods to my shop,” he says. “I have to pay a loan of Rs200,000 that I took from another cooperative. I haven’t been able to pay rent for three months.”

After the cooperative where she deposited her money closed the same evening, Sunita Devi reached the cooperative department in New Baneshwar on February 7. She runs a laundry shop in Baneshwar and her three sons work at the cooperative training and investigation center, within the department. The money they collectively saved—a total of Rs524,500—was deposited at the cooperative. “The cooperative office is shuttered and the officials don’t pick up our calls,” Sunita Devi said.

It is not only the individual clients that the cooperatives have messed with but also organizations. On January 25, advocate Surendra Kumar Bogati had reached the cooperative department after a cooperative didn’t repay his firm’s money. The organization he was involved in, Swayamsevi Abhiyan Nepal, had deposited Rs4.9 million at Hattigauda-based Bright Future Cooperative a decade back.

Cooperative organizations sending employees to collect savings from houses and shops on a daily basis. Photo: Suman Nepali

Between July and December, the cooperative department under the ministry of land management and cooperative has received 451 complaints against cooperatives. Registrar Rudra Prasad Pandit, who was recently transferred from the department, said that during his term, he would hear complaints from at least people daily. “We take complaints if it is under our jurisdiction, if not, we suggest they visit the authorities concerned in local units and provinces,” he said.

The Cooperative Act 2074 has divided the work related to cooperatives’ registration and monitoring among the department, and provincial and local governments. Therefore, there’s no hard data on how many cooperatives haven’t paid their clients money. Meen Raj Kandel, chair of Rastriya Sahakari Mahasangh, the umbrella association of cooperatives, says that as many as 32000 cooperatives across the country have deposited about Rs700 billion.

CEO Prakash Prasad Pokharel of Nepal Saving and Loan Central Cooperative Association, which is a group of cooperatives doing financial transactions, says that those cooperatives have a total of Rs500 billion in deposits.

Kandel says that because of some cooperatives’ fraud, there’s a widespread loss of faith in cooperatives and that has added an extra problem. “On the one hand, the country’s financial outlook is grim, and the cooperatives haven’t been able to get returns on their investment,” he said. “On the other hand, all depositors have been thronging cooperatives to ask for their money back. This has created an imbalance.”

Lack of management and monitoring

After saving and credit cooperatives left people high and dry, the government in 2013 had formed a probe commission to investigate embattled cooperatives. The commission chaired by former justice Gauri Bahadur Karki had made a policy suggestion to not repeat the embezzlement of depositer’s money and secure their finances.

The report suggested that cooperatives should be regularly monitored, formulate strong laws to control unruly financial and managerial decisions, stop registering new cooperatives, branches collecting deposits be shuttered, stop collecting money visiting people’s doors, operators should be stopped from investing without collateral, and all financial transactions be done through banks or financial institutions. But these suggestions were not implemented.

Basic Multi-Purpose Cooperative duping Nardevi’s Bhawani Shahi with a non-cashable cheque. Photo: Ramesh Kumar

Now, a decade since, the situation is hardly different, with many cooperatives getting embattled thanks to mismanagement and people’s deposits at risk. The repercussions of this in society are innumerable.

Karki, the chair of the commission, says that the fact that the same situation has recurred today after a decade proves the government is not responsible towards solving the ills of cooperatives.

The commission had pointed out problems in 162 cooperatives (and their branches), including Oriental. The commission had received complaints from 22170 depositors who had not received an altogether Rs7,607,995,000 from the cooperatives. If interest is included, the sum reaches over Rs10 billion. Among the cooperatives, the Oriental has the most due amount, with over Rs4 billion 160 million yet to be refunded to 7646 depositors.

According to Keshav Prasad Poudel, member secretary of the cooperatives management committee established to refund depositors’ sum, as of November 25, 2022, the cooperatives have to refund as much as Rs3.5billion to as many as 4250 depositors as per their claim.

The fact that Sudheer Basnet, the operator of Oriental, had misused and embezzled large sums of customers’ money only came to light when its branches were locked up. Basnet had opened branches in cities such as Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, Lalitpur, Pokhara, Biratnagar, Itahari and Syangja, among other places. Basnet and his aides had invested the amount in real estate, according to the commission.

Though this misuse continued for years, the cooperative department and other authorities concerned didn’t feel the need to monitor the situation. Even worse, there’s been no concrete step towards ensuring the depositors get their money back.

On November 6, 2017, after five years since the embezzlement came to light, the ministry of land management and cooperatives declared Oriental ‘embattled’. But after Basnet moved the Supreme Court, on July 31, 2019, quashed the ‘embattled’ tag. The court even ordered not to touch Basnet’s property.

On September 23, 2022, the department of cooperatives again tried to tag the Oriental, which hasn’t refunded over 7000 customers, as ‘embattled’, and to take the refund process ahead. But Basnet has again moved the court over the latest decision. Binod Bhandari, one of the victims, says that they are now tired after repeated postponement of hearing. “We didn’t really think that we would have to struggle so much to get our own money back.”

Kashiraj Dahal, chief of the embattled cooperatives management committee, says that because of legal hurdles they haven’t been able to auction Basnet’s property and pay back to his customers. “We couldn’t investigate how much money Oriental really has. After the court’s order, there were hurdles in selling off Basnet’s property and providing it to the customers,” Dahal says.

A decade since Oriental went beleaguered, there have many such complaints against other cooperatives such as Civil, Gautam Shree, Aananda Nagar and Laligurans, among others.

The Department of Cooperatives of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City has sent complaints of 2,800 customers who have not received a refund of Rs917,031,000 principal from 56 saving and credit cooperative organizations to the Nepal Police.

Khotang’s Lalupate Cooperative collapsed without refunding its customers’ savings. The Dhangadhi branch office of Bhaktapur-based Shiva Shikhar Multipurpose Cooperative Organization, on Magh 24, issued a notice of their failure to refund savings before shutting down indefinitely.

The Credit Information Bureau has already enlisted 11 cooperative organizations in the black list in this current fiscal year only.

What is the reason behind the downfall of cooperatives one after another? Gauri Bahadur Karki, chairperson of the probe commission formed to investigate the troubled cooperative organizations, says, “the cooperative organizations could not be regulated. Due to the blossoming of the business of collecting money from the public and mobilizing it in the real estate or other business by a single individual or a family has increased the risk of theft of public’s property.”

What is the reason behind the downfall of cooperatives one after another? Gauri Bahadur Karki, chairperson of the probe commission formed to investigate the troubled cooperative organizations, says, “the cooperative organizations could not be regulated. Due to the blossoming of the business of collecting money from the public and mobilizing it in the real estate or other business by a single individual or a family has increased the risk of theft of public’s property.”

The probe commission led by Karki found that the operators have been abusing the cooperatives by taking huge amounts of loan by the name of the operator himself and relatives and not repaying the principal and interest for years. Although there is a need for guidance and implementation after studying loan files, auditing and internal good governance through field monitoring, it has not been done yet, argues Karki.

Most of the troubled saving and credit cooperatives have one common key problem―operators’ arbitrary investment in the real estate business. The probe commission formed to investigate has concluded that Basnet invested most of the savings of the public in the real estate with the aim to pocket huge income through the betting of land. A study conducted in the year 2070 BS by a committee led by Maha Prasad Adhikari, the then deputy governor (now governor) of the Nepal Rastra Bank, had found that the cooperatives had invested the savings of the public in the purchase of land and private purposes.

A preliminary investigation of the Department of Cooperatives showed that Kuleshwor-based Gautam Shree operator Ram Bahadur Gautam, who has failed to refund about Rs 7 billion savings of the general public of late, also invested in the real estate.

Civil Cooperatives’ operators, including Ichha Raj Tamang, against whom the police have filed a fraud case following their failure to refund the money of savers, had also invested the deposits in the real estate. The charge sheet the police submitted at the court states that Civil Cooperatives used at least Rs 5.67 billion from the public and did not refund it.

Police investigation has shown that the cooperative loaned Rs 1.32 billion to former chairperson and advisor Ichha Ram Tamang’s Civil Homes without securing any collateral. The investigation has also revealed that the cooperatives issued loans again and again without recovering the previous credits.

The Department of Cooperatives and other concerned departments have failed to make proper arrangements to prevent such disasters in time. Although the department issues guidelines related to liquidity, investment, utilization of savings, and institutional good governance from time to time, it has failed to monitor and take action against the cooperatives that show reluctance to implement them.

There is a provision that the cooperative organizations should maintain liquidity up to 15 percent, and invest more than half of the total credit in the production-oriented business in order to minimize the investment in the real estate, but this has not been implemented.

The department, in its monitoring report of the 16 cooperative organizations that were inspected after selecting models in the fiscal year 2077/78 (2020/21), states about the findings of issuing loan to officials without considering their aptness to repay the loan, conducting the valuation of collateral without following proper procedures, not recovering the loan amount that has crossed the deadline, issuing share exceeding the limit, investing loan outside the jurisdiction and collecting savings without approval.

Rudra Prasad Pandit, the then registrar who was recently transferred from the Department of Cooperatives, says,” it is correct that the problems occurred due to lack of effective regulation. The laws should be made strong in order to force the cooperatives for internal good governance, especially regulatory bodies should be made stronger.”

Pandit opines that cooperative and real estate businesses are co-dependent. In fact, the cooperatives start facing problems when cracks start to appear in the real estate business. According to the Department of Land Management, the real estate business is now down to half in the last six months (till the month of Poush) of the current fiscal year compared to last year.

Dhangadhi Branch of Shiv Shikhar Multi-Purpose Cooperative closed due to failure to refund depositors’ money. Photo: Unnati Chaudhary

In the first six months last year, 394,307 houselands were purchased and sold but the number is now barely 189,937 this year. Devendra Prasad Pokharel, chief of Department of Cooperatives of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City, says that most of the savings in the cooperatives were invested in real estate but due to a decline in the real estate business, the cooperatives were unable to return credit. “The complaints lodged here show that almost all the cooperatives invested in the land plotting or land transactions,” Pokharel says.

Mafias hold the key

The concept of cooperative was envisaged as a communal power with minimum resources to run small-scale industries, provide loans for the productive activities, sell the products at reasonable price and make daily goods easily available. The expansion of cooperative organizations that started after the establishment of Bakhan Multipurpose Cooperatives in Chitwan in 2013, took its pace after the formulation of the Cooperatives Act in 2048.

Cooperatives are considered to be an organization that works for the promotion of common welfare of the people of a particular place sharing common occupation, business and objectives. Economist Keshav Acharya says that the cooperatives that should have been established for the communal goodwill were pushed to imperil after the entry of mafias who collect the wealth of the public and use them in betting.

Kasi Raj Dahal, chairperson of Problematic Cooperatives Management Committee, says that although the cooperatives of the dairy and vegetable producing farmers or other community associated with other income generating business or skill development have not faced problems, the activities of cooperatives of saving and loan mobilization with the commercial objectives to pocket money has created problems. “The cooperatives that should be based on the community have become a bridge for the people without external knowledge and people having ill-intention to collect money to earn profit,” says Dahal.

The probe committee formed to investigate the cooperative organizations, in its report, states that the operators who were found involved in misappropriation, while recording their statement, responded saying they were unaware of the principle of cooperatives. “The cooperatives should have been opened after thorough research. There is no one to formulate operation rules,” the report states.

Min Raj Kandel, chairperson of National Cooperatives Federation, says, ”operator and some person seem to have worked carrying ill-intention in some of the cooperative organizations that carry out financial transactions in the urban areas. The operators should re-evaluate their work and responsibilities.”

Closed shutters of Sandhya Cooperative in New Baneshwar, Kathmandu. Photo: Suman Nepali

For instance, the investigation showed that Oriental operator Sudhir Basnet not only was disloyal to the cooperative but also breached the basic ethics of the cooperative. Basnet was found to have taken a maximum loan in the name of artificial persons. Basnet had established more than half-a-dozen cooperatives including Vhegal and Kohinoor Hill Saving and Credit, in order to collect money from the public.

The charge sheet filed by Nepal Police at the Kathmandu District Court reveals that Civil Cooperatives founder Ichha Raj Tamang arranged financial resources to support real estate business from Civil Cooperatives. Even though he was the chairperson of Banijya Bank, Tamang had used the savings from the cooperative. Probe commission’s chair Karki says that most of the operators of the troubled cooperatives started this business with the same malice.

Saving and cooperatives are becoming the tool of money laundering due to the lack of regulations. According to the inspection report of the 16 saving and credit cooperative organizations the Department of Cooperatives studied after selecting models, the 59th report of the Auditor General notes that these cooperatives did not manage risks, failed to establish system to identify suspicious transactions, and failed to conduct a detailed study of the high and abnormal financial transactions from the members.

According to the statistics of the information bureau of the Nepal Rastra Bank, when the departments including the bank and financial organizations had submitted details of 2,780 suspicious transactions in the fiscal year 2078/79 (2021/22), the cooperatives only submitted three such transactions. However, no such activities were reported in the fiscal year 2077/78 (2020/21). It makes clear that the cooperative organizations showed indifference in sending suspicious transactions for investigation when their involvement in large transactions is remarkable as well.

In the fiscal year 2079/79 (2021/22), of the total 2,401,714 transactions above 1 million rupees, 274,113 transactions (about 11 percent) were done in the cooperatives.

Although the details of all the transactions above Rs 1 millions and the information of all the suspicious transactions should be sent to the financial information bureau, the implementation is thin. Of the over 13,000 cooperative organizations that carry out financial transactions across the country, only 405 have installed ‘goAML software’ by the end of last Ashad. Financial information bureau keeps access to the details of suspicious transactions of the organization associated with this system.

Although the Department of Cooperatives has directed the cooperatives that carry out transactions above Rs 10 million to install ‘goAML software’, its implementation remains disappointing, says Deepak Raj Pokharel, section officer of the Money Laundering Prevention unit of the Department. “There is a lack of practice to investigate whether the suspicious transactions were done through the cooperatives,” he says.

International stakeholders have also expressed their worries over the cooperatives that have become a safe house for the money pocketed from corruption, drug trade and the money acquired from the payment of minimal tax while trading real estate.

A delegation of the Asia Pacific Group (APG) under the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) that arrived in Nepal last Mangsir to study the legal provision formulated to prevent the money laundering expressed doubts over cooperatives for abetting money laundering and recommended strong laws and organizational structures, said Pokharel.

Trilochan Pangeni, former executive director of Nepal Rastra Bank, says that cooperatives have become the center of transactions for the people who are enlisted in the black list of banks and financial institutions. “Banks do not trust a person once blacklisted. Cooperative is the center of transaction for a person who has been thrown out of the financial system,” he says.

Threatening cooperative provision

A high-level task force led by National Planning Commission vice-chairperson formed in 2066 to recommend suggestions to address the problems of the cooperative sector had concluded that the cooperative organization conducting financial transactions were a risk-factor for the economy. “A great disaster could be on the cards due to the weak monitoring/regulatory organizational system and legal provisions,” he report states.

A report of the probe commission, 2070 formed to investigate the troubled cooperative organizations had also urged quick action to protect the money of depositors a decade ago concluding that more than Rs 10 billion savings of the citizens was at risk in the cooperatives that carry out saving and credit transactions. But the government did not implement the recommendation of this task force and commission. Other departments also ignored it.

Economist Keshav Acharya argues that no departments seriously analyzed the problems of cooperatives even if they knew the problems persisted. “The government failed in its responsibility to protect the wealth of the citizens. The government became helpless in refunding the savings of the public and taking action against the fraud even though the crime continued in the name of cooperatives.”

Acharya says that his former colleague and a retired former staff of the Nepal Rastra Bank committed suicide after he did not receive Rs 5 million he saved in a cooperative. “A former executive director of the Rastra Bank has also not received Rs 20 million he saved in a cooperative,” he said.

Although the probe commission led by Karki declared 162 cooperatives (including their branches) as problematic and recommended for property management, the government has declared only 12 cooperatives as problematic. Neither actions for management of property and liability has been forwarded against many cooperatives that have failed to refund the savers’ money and have disappeared nor have they been declared problematic.

Karki, the former justice, argues that although it is the basic responsibility of the state to protect the wealth of its citizens, it is the imperviousness of the government for not being able to take a strong decision in favor of victims even though thousands of citizens are falling victims of fraud. “It is surprising to see citizens being unable to get back their savings from the cooperatives that were licensed by the state,” he says.

According to the statistic of the Problematic Cooperative Management Committee, besides Oriental, Kohinoor Hill Saving and Credit, Standard Saving and Credit, Pacific Saving and Investment, Prabhu Saving and Credit, Kuber Saving and Credit, Consumer Saving and Credit, Chartered Saving and Credit, Vegal Saving and Credit, Standard Multipurpose, Societal Saving and Credit and Luniva Multipurpose Cooperative Organization have been declared as problematic. Chairperson Dahal says that except for Oriental, other cooperatives have been refunding the trapped money of savers gradually.

Trilochan Pangeni, former executive director of Nepal Rastra Bank, says that the risk has increased due to the politicization of the cooperatives. He argues that law has been weakened in the effort of the corridors of powers so that the cooperatives could be let free.

“While formulating the Cooperatives Act in 2074, a stern legal action against those committing irregularities in the cooperatives was proposed. But, the nexus of the cooperatives were able to derail such provisions,” says Pangeni. Former justice Karki also argues that the lawmakers associated with cooperatives made the law weak through the concerned parliamentary committee allowing the conflict of interest. “If the Cooperatives Act was made strong, today’s disaster could have been avoided,” he said.

In 2073, after the Rastra Bank drafted the law making the fraud in the cooperatives subject to punishment for banking offense during the first amendment of Banking Offense and Punishment, then Finance Minister Dr. Ram Saran Mahat had registered the bill at the parliament. During the discussion, this amendment bill reached the Finance committee that had cooperatives campaigner Keshav Badal, Civil Cooperatives chairperson Ichha Raj Tamang and other persons associated with cooperatives as members. The committee limited the definition of the cooperative organization to only the cooperative organizations licensed by the Nepal Rastra Bank rather than all the organizations undertaking transactions of saving and credit. As per this definition, the Act would incorporate only 15 cooperatives that had obtained permission from the central bank. As a result, the frauds committed in other cooperative sectors could not be brought to action for banking offenses.

In the bills of the Cooperatives Act 2074, the prohibitory proposals such as defining the limitation of personal savings, regulation of the cooperatives undertaking large amounts through the central bank and the condition of obtaining approval from Rastra Bank to operate a fixed deposit account were withdrawn while formulating the bill.

Tol Raj Upadhyay, vice-registrar of the Department of Cooperatives, views that the regulation authority and the strength of the cooperatives sector were pushed to even more uncertainty after the establishment of federalism.

Today, the cooperatives having one local level as their domain operate under the concerned local level, the cooperatives ranging to more than one local level are under the provincial government and the cooperatives spreading to more than one province operate under the Department of Cooperatives. The Department of Cooperatives also regulates the cooperatives having more than Rs 50 million savings.

“The power to regulate the cooperatives could be developed at the local and provincial levels. Even the federation has only 20 staff. The long-standing deterioration that crept under the lack of institutional regulation has blossomed now,” says Upadhyay.