How have cooperatives supposed to be instrumental in uplifting the poor have instead become mediums to rip them off? The rampant fraud of many cooperatives mushrooming in Dharan Sub-metropolis and the complicity of agencies supposed to be monitoring them and local level representatives provide the answer.

Gopal Dahal |CIJ, Nepal

Fifty-year-old Bidyananda Rishidev of Morang’s Sunbarsi Municipality-6 has his left leg cut off below his knee. Bidyananda, whose leg was cut off during the treatment of cancer, is today seen in Dharan city, extending his hands in anticipation of donation. His family of five depends on whatever little is donated by the helpful.

An elderly participates in a protest organized by Salleri Struggle Committee in Bhanu Chowk, Dharan, on 12 November, 2019.

At the place where Bidyananda today sits to ask for donation, near Mahendrapath, used to lie the Salleri Saving and Loan Cooperative Organization. The cooperative officials coaxed him into save his money for good interest. In six months, he saved a total of Rs 42,000. And one day, he heard that the cooperative operator Krishna Bahadur Bishwakarma had fled after embezzling the money.

Stunned, Bidyananda reached the Area Police Office on his crutch, seeking to get his money back. He called upon everyone he thought could help him but in vain. “I had thought that I’d build my own home even if it was on squatter settlement,” says Bidyananda. “Now I am back to the streets again.”

Another amputated man, Navaraj Chaudhary, 52, of Sunsari’s Barju Rural Municipality-4, Hasanpur, also begs money in Dharan’s streets for survival. Like Bidyananda, Navaraj is a victim of embezzlement in Salleri cooperative. Navaraj also had Rs 42,000 deposited in the cooperative. “I have nowhere left to go to tell of my woes,” Navaraj says. “Now I have let go of the hope of getting the money back.”

There are hundreds of victims like these two men in Dharan—haves and have-nots all. Binod Kumar Rai, an ex British Gurkha soldier who now lives in the UK, is one of them; Rai had deposited a total of Rs 10 million at the cooperative in expectation of good interest. When he heard that the cooperative operator Bishwakarma had fled, on 8 July, 2019, he returned to Nepal in haste and reached everywhere from the local unit office to the police administration. But he didn’t get his money back.

According to the struggle committee formed by the victims of Salleri scandal, the cooperative hasn’t returned a total of Rs 82.3 million deposited by nearly 3000 customers. But a report made by the Cooperative Development Committee of Dharan Seb-metropolis shows a deposit of only Rs 20.7 million.

A press meet called by the victims of Salleri.

After a long time, the fugitive Bishwakarma has been nabbed from Butwal and jailed. Tulasi BK, a former chair of the struggle committee who had deposited Rs 2.6 million at the cooperative, says, “At first, the police didn’t register the complaint. Later, former minister Min Bahadur Bishwakarma sought to protect the culprit. Nobody helped us.”

On January 1, 2021, a total of 183 customers appealed to the submetropolis saying another Dharan-based cooperative Shreya Saving and Loan Cooperative had not returned their money. The sub-metro’s Cooperative Development Committee hosted a negotiation meeting with both the parties. But the money was not returned and the victims formed a struggle committee and repeatedly sat in negotiation table with the cooperative’s operator Lok Bahadur Khapung. Bijay Shrestha, coordinator of the struggle committee, says, “Our calculation showed that the cooperative needed to return as many as Rs 510 million to the customers. The cooperative had Rs 350 million in loan. They had said they would provide us with lands instead of money but in the end, we got nothing.”

Even though Shreya was based in the sub-metropolis’s 15th and 8th wards, it had collected savings from across the district. Meanwhile, the sub-metropolis’s investigation committee found that the cooperative had only Rs 18.5 million in saving. The operator Khapung is yet to be booked as the victims keep protesting.

The Article 79 of the sub-metro’s Cooperative Act 2075 considers it an offense if any one or multiple members of the board of directors embezzle the organization’s saving or shares. The Act further states that the culprit is subjected to six to eight years in prison if the amount embezzled is between Rs 100 million and Rs 1 billion. But the submetropolitan office didn’t advance the punishment process.

The Article 77 states that if the cooperative doesn’t fulfil its liability and is unable to pay its liable, the local unit’s executive would declare the organization crisis-ridden. But Dharan sub-metro has neglected this provision too.

Krishna Bahadur Bishwakarma, the detained manager of Salleri Cooperative

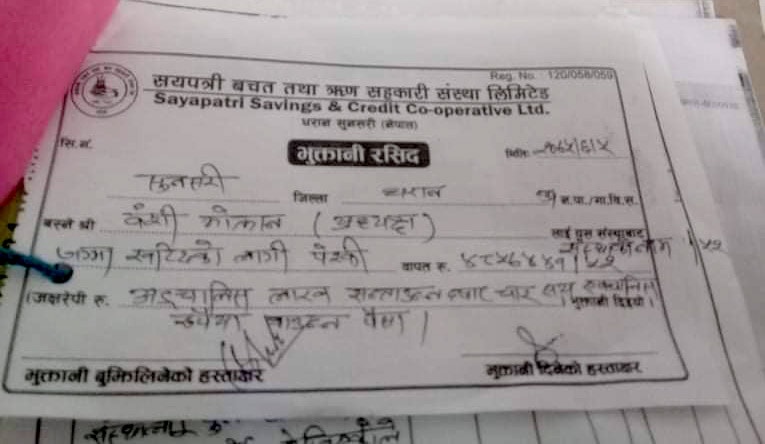

Yet another cooperative in Dharan, Sayapatri, has also embezzled its customers’ savings. The cooperative, whose board of directors includes Dharan-15’s ward chair and the coordinator of the sub-metro’s Cooperative Development Committee Naresh Kumar Ibaram, has embezzled tens of millions of savings, according to an investigation committee formed by the sub-metropolis. The committee’s report shows that while he was the cooperative’s deputy chair and loan coordinator he had invested in dubious projects and used the savings for his personal use. In the audit report of fiscal 2075/76, he has Rs 127, 000 unaccounted-for sum. Likewise, other officials Parbati Shahi and Sharmila Tamang each had Rs 4.085 million and Rs 7.268 million sum that was unaccounted for; in total, Rs 104.091 million was unaccounted for. The cooperative’s meeting minute states that its chair, Bansi Moktan, had given the password to the company’s bookkeeping software to his daughter, who is based in Australia.

Sayapatri’s embezzlement had come to light after the cooperative’s officials filed a report to the submetropolis office and Area Police Office. According to a report prepared by the sub-metro’s investigation committee, Sayapatri needed to pay over Rs 56.3 million by April, 2021. But the report is not released. Moktan however has fled abroad, after appointing his niece as the chair.

Local units as mere spectators

When Limbu, the chair of Bhabisya Cooperative, ran away embezzling Rs 40 million, one of the customers Rashmi Pradhan filed a report with the submetropolis, which formed an investigation committee and summoned Limbu. But he remained out of contact. The officials at the cooperative didn’t let the committee members to check the accounts. The report prepared by the committee states, “Because we were not allowed to look at the accounts, we couln’t investigate.”

Agitated, some of the customers took the cooperative’s computers and furniture. The office is currently shut down. According to Rashmi, the victim, Limbu has told them that he was in Kathmandu and would soon pay off their savings. But after that, he has been out of contact.

Bhabisya Cooperative remains shut down after its manager fled.

After another Dharan-based cooperative, Barah, stopped returning the customers’ savings, the latter are now regularly visiting the cooperative’s office.

These are but a few examples of how cooperative have been swindling customers in Dharan over the past couple of years. Dr Rajendra Sharma, an assistant professor at Mahendra Multiple Campus who has kept a tab on the cooperatives’ fraudulent practices, says that since 2043 BS, over 50 cooperatives in Dharan have swindled their customers. Dr Sharma, who is also involved in various investigation drives, says, “The tendency to rip off customers and rejoice is on the rise.”

Nepal’s constitution has granted the rights to monitor, control and punish the cooperatives to local units. As per the same provision, Dharan sub-metropolitan city promulgated a Cooperatives Act-2075 and formed a Cooperatives Development Committee. According to the committee, of Dharan’s total 87 cooperatives, 78 deal in savings and loans. And it is in these kinds of cooperatives that the fraudulent practices are most rife.

The government has made a provision to keep all the information about cooperatives at Cooperative and Poverty Management Information System. The system, launched by the ministry of land reforms, cooperatives and poverty alleviation, allows local units to monitor the cooperatives. But only 47 of Dharan’s cooperatives have implemented the system. Bhaktiraj Sharma, social development officer at Dharan Sub-metropolis, says, “While cooperatives should only carry out transaction among their members, they are wont to invest in risky sectors. And there is no transparency. Such cooperatives refuse to upload their details to the system.”

Department of Cooperatives imagines that “the activities of cooperatives would uplift poor people over poverty line.” But Dharan’s cooperatives have done just the opposite: instead of helping out the poor, they have pushed poor people further into poverty.

After the fraudulent practices of the cooperatives began to come to light, the submetropolis’s committee found in its monitoring that 11 of 42 cooperatives were crisis-ridden last year. But the submetropolis has kept this report of monitoring secret. According to the report obtained by CIJ, four cooperatives—Chelibeti, Parag, Purbeli and Budhasubba—have been incurring continuous loss while Sayapatri reels under corruption and illicit investments. Chiranjivi Cooperative is also in loss, while there’s a lack of transparency in Dristi, Kriti, and Kripa. Bidhyadhari and Anmol, meanwhile, have already been shut down, the report states.

A passbook issued by an unregistered cooperative based in Dharan-17.

This year, of the 54 cooperatives monitored, 17 were found crisis-ridden. Of them, offices of cooperatives such as Hiuchuli, Bhanu Pathibhara, Sunkoshi, Mahila Subha Jagriti, Bhar-abhar, Suryakiran, Shramjivi, Parishrami, Aatmanirbhar, Anmol, Pahilo Kadam, Gyankunj, Bidyadhari, Kripa, Chelibeti, Sayapatri, and Purbeli, among others, couldn’t be located, and they were operating without an office, according to officials involved in monitoring. While the cooperatives with security guards, cctv, big screens and modern furniture had their accounts messed up.

Last year’s monitoring report showed that a majority of Dharan’s cooperatives didn’t conduct their general assembly and auditing in time, went outside their remit to collect savings luring customers with promises of good interest, and invested savings in non-financial sectors, and benefitted only the directors and officials and not customers. Likewise, the report also shows that there was negligence in management, misuse of savings, monopoly of board of directors, and the cooperatives didn’t distribute profit to members, and didn’t formulate internal policy and methodology.

Cooperatives in Dharan metropolis have a total of 25963 members, with Rs 2 billion 656 million 12 thousand rupees. The total share investment of members is Rs 4.866 million. The cooperatives’ loan investment is Rs 2 billion 746.9 million and 96 thousand. But this is only the statistics presented to the submetropolis office by the cooperatives. About half of the cooperatives haven’t presented their statistics at all.

Local units seem uninterested in booking cooperatives that run with rampant irregularities. Bhaktiraj Sharma, section officer at Dharan sub-metro’s cooperative department, however, says that his office has corresponded with the cooperatives and some have promised to improve their modus operandi. He argues, “We haven’t stayed silent. We are in active correspondence and will punish if they don’t improve their ways.”

Investing savings in Hundi, real estate and gold

So where do the cooperatives invest the savings which the customers can’t get when they need? We found that most of Dharan’s cooperatives invest most of the savings in Hundi transactions, land and gold.

In one instance, Salleri cooperative invested Rs 6.8 million 89 thousand in a gold shop, states the report from the submetro’s investigation committee. That shop belongs to chair of the cooperative, Krishna Bahadur Bishwakarma. To aid to this transaction, Bishwakarma appointed his son Mohan Darnal as a manager and his wife’s daughter as accountant, against the provision of the Cooperative Act.

Lok Bahadur Khapung, manager of Shreya Cooperative, cooperative committee coordinator Naresh Ibaram and Nepal Congress leader Min Bahadur Biswakarma

As many as 183 customers swindled by Shreya cooperative have filed a complaint at the submetro office. But through investigation, only 108 names were found in the cooperative’s records. And again, only 36 had savings in the cooperative and 20 had shares, according to the report. Lok Bahadur Khapung, the manager of Shreya who runs Easy Rider Goldshop, Easy Rider Hotel and Dharane Pani water company, is also a real estate agent. While he was formely involved in collecting saving and providing loan with the use of ‘passbook’ from his gold shop, he had later registered his cooperative Shreya after government’s strict policy post 2011.

Those in the know say that while he shows the transactions take place via the cooperative, a large sum is transacted through his gold shop even today. Khapung would lure the customers saying the cooperative would provide 22-24 percent interest in savings. He had invested the amount collected thus in gold, Hundi transactions, and land. The Hundi transactors in Dharan openly say that they had transacted through Shreya. Officials who investigated Shreya also say the cooperative was involved in Hundi transactions. But the investigation report has no mention of it.

To those asking their saving back, Khapung today says that he’d pay back in land, but he has tagged the price of land double the market price. And he has appointed Devi Prasad Subba as the chair of the cooperative, seeking to escape from the debacle.

Many big gold shops in Dharan have their own cooperatives. For instance, Barah Jewellery. Barah, which trades gold in not just Dharan but also Pokhara, Kathmandu, Chitwan, and even Hong Kong and the UK, used to publish its own ‘passbook’ and attract savings, which it would invest in gold. It later registered a cooperative and it invested the saving collected there also in gold, Hundi transactions and personal property. This aspect of Barah was revealed after it purchased a new building in Dharan.

The investigation by the submetro office shows that the directors at Sayapatri Cooperative invested the customers’ savings in a gold company called Sayapatri Remigold and also in a networking company called Crystal Vision. It is found that another cooperative Prakriti has also invested customers’ savings in private property.

Protection to the frauds

Nepal’s constitution and the Local Unit Operation Act have considered public-private cooperatives as the major pillars of economy and have set goals to encourage public to saving, uplift standard of life and decrease poverty through cooperatives.

Once the country adopted federalism, local units got the responsibility for urban development and monitoring, but they seem like meek spectactors against the fraudulent practices of cooperative managers. So much so that instead of punishing the managers, many local unit representatives, cooperative committees and political leaders have given protection to them.

A bill shows advance amount taken by Banshi Moktan, chair of Sayapatri Cooperative.

After Krishna Bahadur Bishwakarma, manager of Salleri, went out of contact since July 8, 2019, customers filed a report to Dharan Submetropolis’s cooperative committee coordinator Naresh Ibaram Limbu. On July 11, they filed a complaint against Bishwakarma with the Area Police Office.

Ibaram is a local of Dharan-15, where Bishwakarma’s home also lies. But for a long time Bishwakarma was ‘not located’ for the submetropolis office. To save Bishwakarma’s property, former minister and Nepali Congress central committee member, Min Bahadur Bishwakarma, was also active. On July 9, Ibaram recommended the sale of one katha land and a house based on it that was registered on Krishna Bahadur’s wife Bishnumaya’s name. A week later, former minister Bishwakarma transferred the registration of that property to his wife Dambar Kumari Poudel’s name at Rs 7 million. Krishna Bahadur and Min Bahadur are business partners. They had established a poultry company Chicken Valley in Dharan-8. But once Krishna Bahadur was detained, the company couldn’t go ahead.

Amar Ijam, a local leader associated with Sanghiya Limbuwan Manch and one of the customers, got another of Krishna Bahadur’s land some gold. Other customers, however, became empty-handed. After which, they protested on the streets, sloganeering against Min Bahadur and ward chair Ibaram.

Former minister Bishwakarma, however, claims that he has not protected Krishna Bahadur. “The victims got me wrong. I have instead helped the police detain him,” he says. “I had already bought that house and its legal handover was delayed.”

Ibaram is also involved in protecting Sayapatri, another cooperative. Ibaram himself is associated with this cooperative. On April 6, 2021, a meeting attended by Ibaram, who is the cooperative’s former vice chair and a share member, decided to take the issue of forgiving the loan of Rs 4.857 million taken by former chair Banshi Moktan to the cooperative’s special general assembly. Moktan, an UML leader, is deputy chair of then Sunsari VDC. Ibaram is a local leader of UML.

When he was the chair of the cooperative, Moktan had taken a loan keeping gold as collateral to establish Remigold company, which would have tripartite share of Moktan himself, his brother Bhuwan Moktan and the cooperative. In this move to share the profit among three parties, the Moktan brothers would have to bear the two third of the shares, but the cooperative’s meeting decided to relieave them of all Rs 4.6 million.

The cooperative had filed a report with the submetropolis saying that Moktan had fled even while the accounting process was not complete. But the meeting decided to retrieve the complaint and not correspond with Moktan anymore. Not only that, Ibaram also pressurized the cooperative to relieve his relative brother Bipin Subba Ibaram of the loan he had taken. The minute of that meeting states that former chair Ibaram had submitted a appeal to ‘adjust’ the loan taken by Bipin Subba. Ibaram, however, claims that former chair Moktan had taken an advance amount to purchase the organization’s land, the reason why the loan was relieved.

Fraudulent leaders

In the latest irregularities of Dharan’s cooperatives, the role of the submetro’s cooperative development committee coordinator Naresh Kumar Ibaram appears to be most suspect. He himself is a cooperative manager and also a regulator. Instead of booking the cooperatives, he has protected them.

Ibaram has obstructed the implementation of the investigation committee’s recommendations. A member of the cooperative says, “He didn’t let us release the report, and also obstructed the punishment of Sh’eya’s manager because of a personal relationship with him.” That manager who has embezzled millions of rupees is still at large, with no legal repercussions yet. Ibaram says to the victims, “Why would you want to get into legal hassles? Instead, take land or money from the mananger in good terms.”

Can anyone who is himself a regulator do this? Upon being asked this question, Ibaram claimed that if the case moves to court, the victims risk losing their savings altogether, hence he was advocating for a peaceful resolution.

Legally, a cooperative can’t be bought or sold. But Ibaram is involved in trading cooperatives. He purchased a crisis-ridden cooperative Sarathi and sold it.

Another crisis-stricken cooperative Bhabisya has been traded four times. Its fugitive manager Indra Limbu had conceded in a phone call that he had bought the cooperative. Another cooperative Purbeli, where Mishan Lama, the submetropolis’s cooperative committee member, is a deputy chair, has also been bought. Hema Thulung, the sub-metropolis’s cooperative investigation committee member, says, “In investigation, we found that many cooperatives were bought and sold. The buyer would at first be nominated a share member and later as chairman to fix legal hurdles.”

Many of Dharan’s cooperatives are being managed by political leaders and their relatives. Which is why, the submetropolis’s cooperative committee doesn’t forward the punishment process. If the officials move ahead to punish, then local unit representatives pressurize them to move back. An official with the submetropolis office says, “We try to punish according to the law, but the leaders threaten to punish ourselves instead.”

Assistant professor Dr Rajendra Sharma says that it is a wrong move to provide the rights to monitor cooperatives to local units. “Local unit is a grassroots organization that seeks to develop the area. It is wrong to provide it with the responsibility to regulate cooperatives,” he says. “Because a local unit is an area where pressure from political parties is rife, allowing it the monitoring rights gives rise to corruption and impunity. Culprits are let scot-free. This is exactly what is happening in Dharan.”