The court hasn’t held anyone accountable even when a DNA sample, considered an important piece of evidence in criminal cases, sent for testing was tampered with. Result: The powerful are extracting results from labs to suit themselves and avoid punishment in criminal cases.

Man Bahadur Basnet |CIJ, Nepal

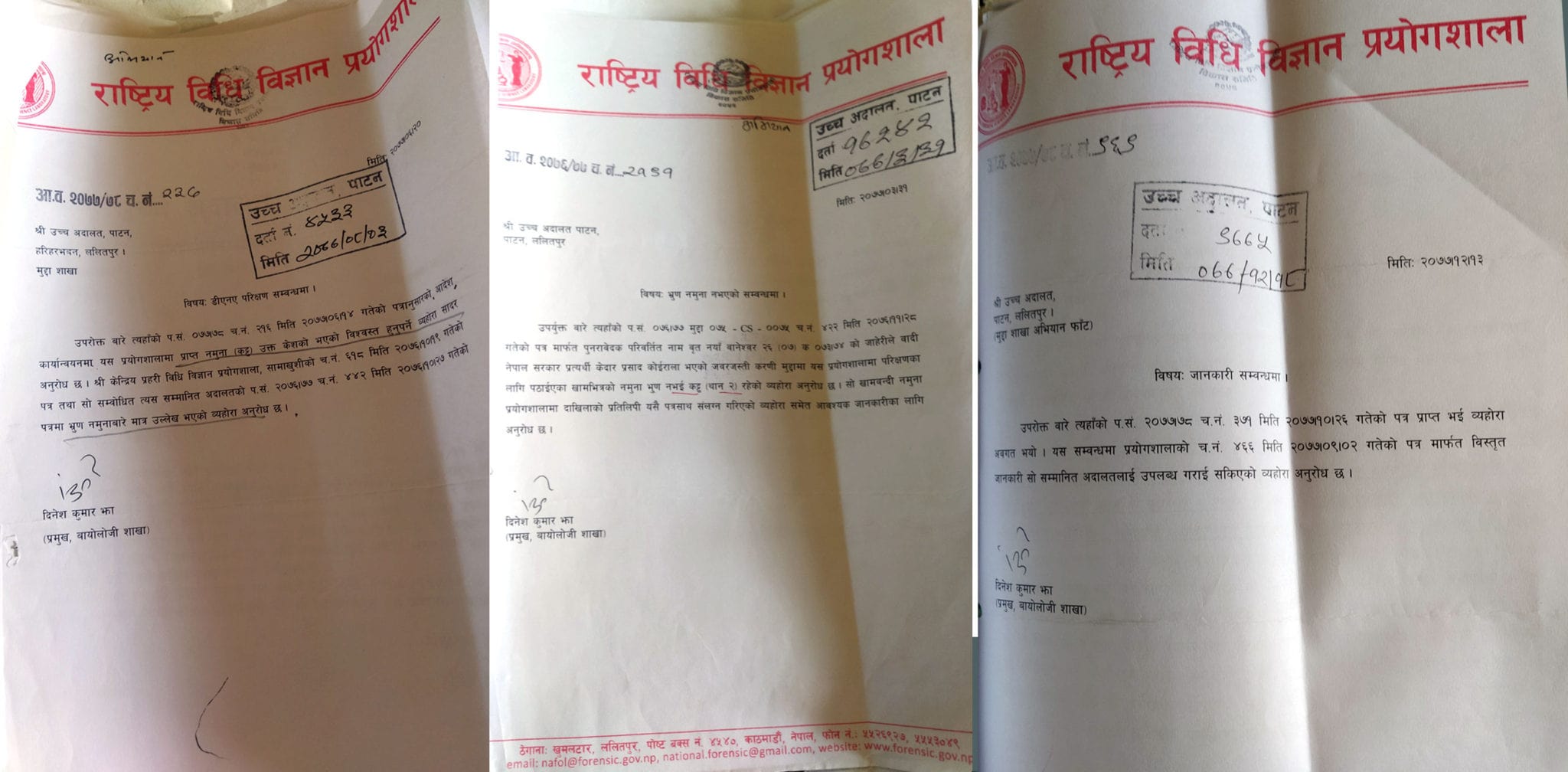

The Patan High Court, the Central Police Forensic Laboratory, and the National Forensic Laboratory are not located far from one other. However, according to a court report, it took exactly one year for a test sample to reach the National Forensic Laboratory, Khumaltar, from the Police Forensics Laboratory in Samakhusi, around 14 kilometres away.

In a case related to rape, the court ordered a DNA test on June 30, 2019, and received the results on July 15 of 2020. The contents of the sample were equally surprising.

The court had ordered that DNA samples of a feotus, conceived allegedly after rape, be sent to the National Forensic Laboratory after the police forensic laboratory failed to do so. However, the National Forensic Laboratory, a year later, had replied to the court that it didn’t receive any samples from the foetus. It only received a pair of undergarments.

Even after receiving such a letter, the court ordered the lab in writing thrice (on September 22, November 29, and February 7) to send the report after conducting a DNA test. The lab replied with the same answer.

Negligence in handling evidence

Journalist Kedar Koirala, who was accused of raping a girl living under his protection, was acquitted by the Kathmandu District Court on March 19, 2018, based on the DNA test report. However, Koirala approached the Patan High Court with an appeal against the district court’s order to pay the minor Rs 1 million in compensation. The aggrieved party also knocked on the door of the high court as it was not satisfied with the acquittal.

The sample foetus was replaced by a pair of undergarments when it reached the Khumaltar laboratory from the police laboratory. The court did not order an investigation into it despite repeated requests for test reports.

The high court found Koirala guilty on April 25, 2021, by not considering the DNA test as evidence as the DNA sample was found to have been tampered with. The court didn’t hold anyone accountable for the gross negligence in the handling of physical evidence, an important tool in the administration of justice.

Dr Dinesh Kumar Jha, head of the Biology department and information officer at the national laboratory, said that when lab technicians opened a sealed envelope containing the sample sent by the police forensics lab, they were shocked to see a pair of undergarments instead of samples from a foetus. He said that the technicians had opened the envelope in front of the person who had brought the sample to them, taken photos of it, and sent it to the high court.

Journalist Koirala has again approached the Supreme Court seeking acquittal, saying that the DNA test didn’t confirm his involvement in the crime. The case is now sub-judice.

An indifferent court

Physical evidence is considered an important tool in facilitating the administration of justice. Advocate Subash Acharya, a criminal lawyer, said that physical evidence helps both the investigator and the judge to determine whether the accused is guilty or not. “A person may be biassed, but physical evidence is impartial,” he said.

According to Acharya, the criminal justice system has been plagued by the practice of tampering with physical evidence, distorting test results, delaying tests, and preparing inaccurate reports. However, the court hasn’t ordered an investigation to hold those responsible accountable, nor have the investigating bodies themselves become accountable. Such practices increase the risk of the guilty getting acquittal and the innocent getting punishment. Both the plaintiffs and the defendants of the criminal case tried to prove themselves right by referring to test reports prepared by negligent investigating bodies and laboratories.

Obstacles to justice

On the evening of November 18, 2017, at Godamchaur in Lalitpur, some youngsters gang-raped a 21-year-old woman and rendered her unconscious by stoning her. The woman, who was left for dead, regained consciousness in the hospital the next day. With the help of her family, she filed a complaint against Pawan Kunwar, Raghu Silwal, and Vishal Dhwaj Karki.

The police sent the victim’s vagina swab to its laboratory in November 2017. As the lab didn’t provide a report even after a week, Inspector Sundar Chaulagain of the Metropolitan Police Circle Satdobato, wrote to the lab on November 29 asking for the report. It took the lab another month to report that semen was found in the swab.

The Satdobato police office again requested the lab to profile the DNA from the semen sample. After not receiving a reply for two weeks, the office wrote to the lab again on January 6, 2018. However, the laboratory replied it had run out of kits used for DNA testing.

After the test, it is customary to return the sample to the place from which it was sent. I can’t say how a pair of undergarments replaced the foetus.

– SSP Rakesh Singh, head, police forensics lab

It took the lab another four months to procure the kit. The DNA profile report was sent to the Satdobato police on in May 2018. The report stated that the profile didn’t match those of the accused. The report said that although it was evident that more than one person was involved in the incident, it didn’t say Kunwar Silwal and Karki were the perpetrators.

The human body has 23 pairs of chromosomes, including 22 pairs of autosomes and a pair of sex chromosomes. A woman has an XX and a man has an XY sex chromosome. Forensics expert Dr Jeevan Prasad Rijal and former executive director of the Central Forensic Laboratory said both sex chromosome and autosome testing should be made mandatory in rape cases.

The Y chromosome is to be tested to find out how many people were involved in the incident and the autosomes are to be tested to determine who was involved, Rijal said. However, in the Godamchaur case, only Y chromosomes were tested, said Rakesh Singh, Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP) at the Central Police Forensic Laboratory, in a statement filed at the District Court, Lalitpur.

The district court sentenced the trio to five years for rape, five more years for gang rape, and another 10 years for attempted murder. However, Kunwar , Silwal and Karki appealed to the high court saying that the DNA test didn’t confirm the allegations. The accused have now approached the Supreme Court after the high court upheld the verdict of the district court.

In this case, the two courts, however, didn’t even question the delay in the laboratory test and the reliability of the method used. The court did not question whether this was done deliberately to influence the trial or not. However, the role of the laboratory in criminal investigation and prosecution in cases ranging from journalist Kedar Koirala to Godamchaur and the Nirmala Pant case has raised many eyebrows.

In the case involving the rape and murder of Nirmala Pant in Mahendranagar of Kanchanpur in 2018, there is a list of errors the police lab made in conducting a DNA test of the victim’s vaginal swab. An expert committee set up by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to look into the case said that the laboratory had disposed of the vaginal swab of the victim after reporting that the DNA of the sample did not match that of the prime accused Dilip Singh Bista.

The committee, led by the former executive director of the National Forensic Laboratory Dr Jeevan Prasad Rijal, had found errors in the police laboratory’s procedures from sample collection to testing. The committee noted that the sample from the vaginal swab was tested for DNA even when semen was not found in it. Similarly, DNA testing protocols (standards) were not followed and rules related to the chain of custody (details of persons or organisations transferring samples from one person to another, and details of persons involved in laboratory testing) were not respected.

The government didn’t implement the commission’s recommendation to take action against negligent officials. As a result, the same problem arose in the case of Kedar Koirala. ” The whole process is rife with errors,” said Dr Rijal. “These kinds of errors obstruct the administration of justice.”

Culture of inaction

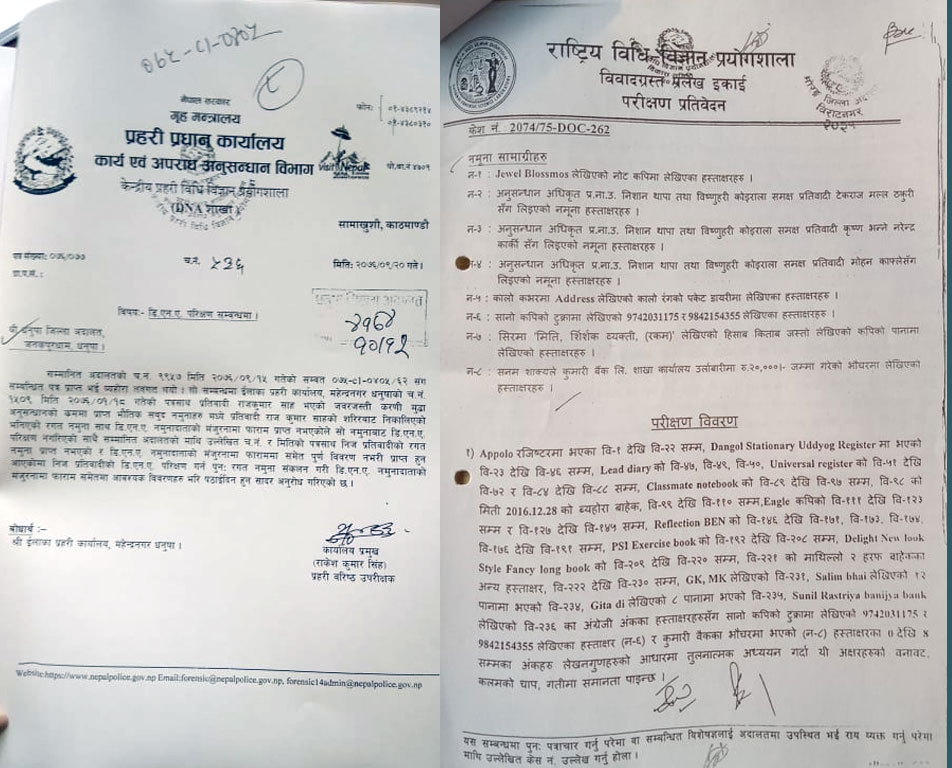

A case related to the smuggling of 33 kg of gold and the killing of Sanam Shakya was filed at the Morang district court on July 4, 2008. The district attorney’s office had moved the court based on the findings of a report prepared by a committee headed by Home Ministry Joint Secretary Ishwar Raj Poudel.

Police Laboratory in Samakhusi.

The committee had found hand-written notes on financial transactions in a diary recovered from the accused. A forensic examination was ordered to determine whether the handwriting belonged to the accused. The committee also sent the sample to the national lab in Khumaltar as it didn’t trust the results from the police laboratory.

An officer considered a close ally of the then Inspector General Sarvendra Khanal was also involved in the incident. A police official on the committee said that the sample was also sent to Khumaltar, as the lab’s results may be influenced by the chain of command.

This shows that it is possible to get the desired test report from the police laboratory by abusing power and access. Lab test reports help to narrow down the criminal investigation and identify culprits and as they are based on science, they should not so frequently run into controversies. However, Superintendent Rakesh Singh, the chief of the police laboratory, who was repeatedly found to be negligent, was promoted to the post of Senior Superintendent and was assigned the same workplace.

When the National Human Rights Commission recommended action against him in August 2018, SP Singh was the head of the police laboratory. During his tenure, the role of the police laboratory played in investigating pieces of evidence in criminal cases such as the Godamchaur case, Nirmala Pant case and Kedar Koirala case courted controversy.

The police laboratory further complicated matters in a rape case in Dhanusha. Rajkumar Sah of Chhireshwar Nath Municipality-5 was accused of raping a 14-year-old girl on April 28, 2019 by making her unconscious. Area Police Office, Mahendranagar, sent a sample of the vaginal swab of the victim to the police lab three days later, But the laboratory informed after six months that the test couldn’t be conducted as the accused didn’t consent to it.

Five days later, the Dhanusha District Court ordered a DNA test, but the laboratory again told the court it couldn’t carry out the test without the consent of the accused. When the accused, detained at the Jaleshwor prison, consented to get tested, the lab informed that it couldn’t run the test as blood samples were not sent along with the consent letter.

Police Laboratory chief SSP Singh told us that it takes one to six months to prepare the report for a DNA test. The National Forensic Science Laboratory can issue such reports within 30 to 45 days, said information officer Dinesh Kumar Jha.

The reports issued by the police laboratory after taking six months to carry out tests have also been dragged into the controversy. When asked about how samples were tampered with in Kedar Koirala’s case, SSP Singh, expressed his ignorance about the case. “Usually, the test sample is returned to wherever it came from,” he said. “I can’t say how a pair of undergarments made it to the sample.”

According to a letter sent to the Patan High Court, the police lab returned the sample to the Naya Baneshwor Police Circle after the test. SSP Singh told us that DNA from the foetus couldn’t be extracted due to a lack of testing technology as the foetus hadn’t developed its femur bone.

The National Forensic Laboratory had asked the police headquarters to send the fetus’ amniotic fluid to conduct DNA tests before abortion was carried out. The letter sent to the Police Headquarters on May 2, 2021, was also dispatched to the Office of the Attorney General.

A test report sent to the district court by a police laboratory said the fetus was shaped like a human hand. Surprisingly, DNA couldn’t be extracted from such a fetus, said Dr Jeevan Prasad Rijal.

“If DNA can be extracted from semen and ovaries, then why not from a fetus?, ” he questioned. “If the police don’t have the capacity to do so, why not send the sample to a place equipped with the required technology?”

The Naya Baneshwor Circle had handed over the sample returned from the police laboratory to the Kathmandu District Court along with the case files.

DNA testing is going on blindly in Nepal. Since the results of DNA testing can sometimes disturb family and society, there is a need for legislation to dictate what to test for and what the role of the laboratory should be. However, these days DNA testing is done whenever someone feels like it.

– Lava Mainali, senior advocate

The foetus was under the possession of the Naya Baneshwor Circle, District Court, Kathmandu, the Patan High Court, and the National Forensic Laboratory at different times. It is not possible to exchange the foetus for a pair of undergarments without the connivance of one or all of these bodies.

That a piece of evidence that could prove the guilt of the accused in the crime was tampered with shows that another criminal act was committed during the scientific tests. But no one inquired as to who was responsible for this. During the Panchayat period, many were sacked for committing such crimes.

Panchayat-era example

During the Panchayat period, investigations into corruption were conducted by the Special Police Department. According to Padmaraj Kafle, senior advocate, in the 1970s, Ram Bahadur Thapa was an inspector in the Special Police Department. Shanti Mishra, head of the library at Tribhuvan University, had been accused of embezzling Rs 1.5 million by forging the signatures of the accountants.

Kafle recalls being assigned by the court to study the allegedly forged documents. “When I told the court that it was the accountants, not Mishra, who had forged the documents, the documents were sent to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), India.” He added, “She was released when the same opinion came from the CBI.”

After that, the special police removed Thapa from the responsibility of checking forged documents. The whole section was later closed, advocate Kafle mentions in his book.

At present, however, no one has been held accountable for the errors made by the police laboratory in DNA testing.

Credibility under question

The police laboratory was established in 1960. The laboratory, which was initially limited to photography, now has 10 sections to investigate cases related to drugs, explosives, fingerprints, poison, ballistic, disputed documents, and DNA profiling.

DNA testing is being carried out at the forensic laboratory of the police in Samakhusi.

The laboratory remained shut for six years after it was recognised that the body providing expert services in crime investigation and the justice system should be independent. On the recommendation of the Royal Judicial Service Reform Commission, the government closed the Police Laboratory in 1988 and established an autonomous national laboratory in Khumaltar.

But in 1993, the government decided to reopen the police laboratory. The Danish government, which provided financial support, had stipulated that biological samples not be tested at the laboratory.

“The Danes’ pre-condition was that only physical evidence, including bullets, khukuris, and knives, whose quality would not be degraded after each test, should be conducted at the lab, ” said Dr Rijal. “But the police started testing all the samples.”

As the organisation runs on a chain of command, the top can influence the results and if there is a dispute, there will be no sample left to be tested again, Rijal explains. The present situation emerged after the police didn’t respect the pre-condition set by the Danes, he added.

According to him, forensic labs in the UK are not under the control of the police as the scientific testing laboratory should be autonomous. He said, “ This is because the police who follow orders can’t ignore instructions of their superiors and the result may be affected.”

Former Deputy Inspector General of Police (DIG) Hemant Malla Thakuri said that as reports prepared by the police laboratory have courted controversy, there are concerns that the lab may not be functioning independently.

“The police laboratory was closed because a scientific testing institute should work without pressure. He says, “It is not good for the police to get involved in a dispute by restarting the lab. It should identify where the problem is and resolve it. ”

He says that the credibility of scientific tests conducted by the Nepal Police, which is highly influenced by the political parties, is itself questionable. After all, every DNA profiling done by the police lab in the last eight years has been controversial.

A laboratory without a heart

When prescribed protocols are strictly adhered to, DNA testing is considered the most reliable source of evidence in modern science. According to senior advocate Lava Mainali, who specialises in criminal law, there is a universal belief that only one in a million DNA tests can be erroneous. In Nepal, however, the same DNA report has been seen to confuse everyone involved in crime investigation with justice.

Rijal remembers that when he was the executive director of the National Forensic Laboratory, the then Inspector General Upendra Kant Aryal had sought his help to run the DNA lab. ” I had told him that I could help only after the internal guideline was prepared, “ he added. “But as there are no guidelines, everyone can do whatever they want. No one has to take responsibility for errors. Because of this, criminals are evading punishment.”

Dr Rijal considers the guidelines to be the heart of the laboratory. Therefore, he thinks that the forensic laboratory of the Nepal Police is running without a heart. He urged the police not to run the laboratory without formulating its guidelines. During his tenure as director of the National Forensic Laboratory, Rijal even drafted the standard operating procedures.

Rijal led the Khumaltar Laboratory for two terms (2003-2007 and 2013-2018). But the draft standard operating procedures he presented before the board, led by the Education Ministry Secretary, hasn’t been approved it and the lab is also still running without its guidelines.

The draft submitted in December 2014 included provisions related to the chain of custody, the test method, archiving of who did what from sample collection to report preparation, and management of leftover samples after testing.

Information Officer at the National Forensic Laboratory Dr Jha says there is a risk that results from a lab running without a standard operating procedure may not get international recognition. There are also many instances where laboratory reports without standards have been disputed and not re-tested. However, it is not clear who is responsible for re-examining the evidence. Samples are not kept safe after testing at both the police and Khumaltar laboratories. Chief of the police laboratory SSP Singh said that the samples are not stored after they are tested.

Dr Jha from the National Legal Science Laboratory says that his lab returns samples to those receiving the report. ” We don’t have a safe place to archive the samples, ” he said.

It is clear from the statements of these two responsible officials that no one cares that a re-examination of the evidence might be necessary until an investigation of the criminal incident is completed.

‘Fraud’ in the laboratory

Madan Thapa, 21, of the erstwhile Arunodaya VDC of Tanahu, filed a case in the district court on April 28, 2016. He had gone to court after his father Kshetra Bahadur Thapa deprived him of his share of parental property saying he was not his biological son.

After samples were taken from both Madan and Kshetra Bahadur Thapa for DNA testing, the court sent them to the reconciliation centre saying it was a family dispute. Such cases are referred to the reconciliation centre by appointing a listed advocate at the request of both the parties or at the behest of the bench itself. The controversy took a different turn when Kiran Prasad Bhattachan, a person with no locus standi in the case, broke into the reconciliation centre and insisted that the report of the DNA test be accepted.

In the United States, there is a mechanism to check whether a verdict is correct or not, even if convicted by a final court. This allows the court to correct its weaknesses. In Nepal, there is nobody to review cases decided on faulty grounds.

– Subash Acharya, advocate

Later, it was found that Bhattachan was a witness of the defendant. It was also revealed that he had come to Kathmandu during the DNA test. A bench of Justice Rajendra Kumar Acharya on September 5, 2017 ruled in favour of Madan Thapa, rejecting the independent status of the test as Bhattachan had already found out the results and found that the DNA test itself had been compromised.

The judgement states: “This bench strongly rejects the tampered DNA report in an unpleasant and harsh manner. The test was not authentic”. The bench also directed the National Forensic Science Laboratory to ensure that such mistakes are not repeated in the future.

This was not the first time that the court raised such a question alleging forgery in laboratory tests. The court had raised similar questions in the case of Rajiv and Nita Gurung.

Rajiv Gurung of Chitwan had gone to court in January 2002 after his girlfriend Nita gave birth to a son. Rajiv rejected that the child was his and the case reached the Supreme Court in 2005. Nita had demanded that the court uphold the marital relationship between the two and that the child is recognised as Rajiv’s son.

When the Supreme Court ordered a DNA test to resolve the case, the National Forensic Laboratory reported that the DNA of Rajiv and the child didn’t match. On the other hand, the other party questioned the fairness of the test saying that Rajiv had taken another person with him inside the laboratory when providing a sample for the test.

Nita’s lawyers called for a halt to the investigation, questioning the validity of the report and that the sample was taken in the absence of a representative of the plaintiff. The apex court did not approve the report, as it had been influenced by one of the parties to the case.

A bench of justices Balaram KC and Sushila Karki on May 25, 2010, ruled that the samples should be taken as evidence in cases where they are undisputed. In other words, the court said that only if the laboratory test is done independently, the evidence will be admissible in court.

“DNA tests are important in paternity disputes and criminal investigations,” the ruling said. This bench does not dispute this matter. But for the DNA report to stand as evidence, only the person concerned and the related expert should enter the laboratory room to get the sample.”

The court ruled that although the results of DNA testing were reliable in the administration of justice and criminal investigation, the testing process should be up to acceptable standards.

It is clear from these two cases that tests in Nepal don’t follow the rules and standards and confuse investigators.

Lack of review mechanism

Advocate Subash Acharya says that there is no mechanism in the judicial system of Nepal to re-examine court decisions.

According to him, following the availability of DNA testing technology in the United States in the 1990s, cases related to many people who were sentenced to death were re-examined and they were found to be innocent. A study by the Benjamin N. Cadozo School of Law at Yeshiva University, in collaboration with the US Department of Justice and the Senate, found that 70 percent of the guilty had been falsely accused. They founded the Innocence Project, a non-profit in New York, in 1992 that freed more than 350 people and helped reform the criminal justice system.

Documents related to 33 kg of gold smuggling and murder were tested in Khumaltar, not Samakhusi.

According to Advocate Acharya , in the United States, there is a mechanism to check whether the verdict in a serious case is correct even if the final court finds a defendant guilty, which allows the court to rectify its weaknesses. “ In Nepal, we don’t have such a mechanism. “That is why error-free scientific tests are more important for our justice system.”

No uniformity court’s perspectives

Laxmi Shrestha of Dhading, who tied the knot with Ravi Shankar Mishra of Kathmandu in the 1990s, later found out that she was his second wife. After giving birth to a daughter two years after the marriage, she filed a lawsuit claiming a share of his property.

Ravi’s mother Makhamali Mishra appealed to the Supreme Court after the district and the appellate (now high) courts ruled in Laxmi’s favour. She held that as Ravi was not her biological son, even Ravi couldn’t claim a share of her property, let alone Laxmi. She demanded that a DNA test be done. The test report showed a DNA mismatch.

On May 12, 2010, a bench of justices Ram Kumar Prasad Shah and Tahir Ali Ansari ruled that Laxmi Shrestha should not receive a share of the property as so the DNA test, the most scientific and reliable test ever, showed Ravi was not Makhamali’s biological son.

After Laxmi filed a petition for review of the case, the full bench of the apex court on January 19, 2017, ruled that Ravi was Kedar and Makhamali’s son and that the DNA test was brought up with the intention to erase his inheritance rights.

The Supreme Court explained that referring to the DNA report was a prerogative of the court and not of the parties to the case. The court concluded that there was no need for a DNA test to reach a decision as it was confirmed from other documents that Ravi was indeed the son of Makhamali and Kedar Mishra.

DNA used without relevant law

When investigating a criminal case, a laboratory has to generate as many results as possible from the limited evidence while retaining the sample. Former Executive Director of the National Forensic Laboratory Dr Rijal says that if results obtained from one method are to be verified with the results obtained from another, keeping the sample safe becomes more important.

The events that unfolded in the Nirmala Pant case show that these precautions aren’t taken in Nepal. Even the court order to prepare separate legislation for using DNA evidence has not been complied with.

The government hasn’t complied with the directive issued by the bench of Supreme Court Justices Balaram KC and Sushila Karki in 2011 to enact a DNA identification and evidence act. As a result, DNA testing, which plays a key role in criminal investigations and the administration of criminal justice, continues to be carried out without a relevant law.

The apex court had ordered the government to prepare a law in this regard saying that there was no mechanism to assess when a sample is to be taken and how it is to be kept safe. In addition, the court ordered the establishment of a data bank for DNA profiling.

The DNA data bank keeps records of those convicted of criminal offences. If there is a suspicion of a repeat offence, the DNA of the accused can be obtained from the data bank without his knowledge, Rijal explains.

Senior lawyer Lava Mainali says that DNA testing is going on blindly in Nepal. He said that since the results of DNA testing sometimes disturb the family and social status, the criteria for testing and the role of the laboratory should be determined by law. “ It doesn’t work when DNA tests are ordered whenever someone wants them, ” he says.

Supreme Court Judge Tahir Ali Ansari had issued a show-cause order in the name of the government while hearing the writ petition filed by advocate Khagendra Subedi and others in June 2011 against the government for not enacting the law. Even after a decade, a verdict hasn’t been issued in the case.

DNA testing without proper laws, norms, and procedures to back it up risks giving the offender a chance to escape punishment. Senior Advocate Lava Mainali says, “Our criminal justice system is in a shameful state.”.