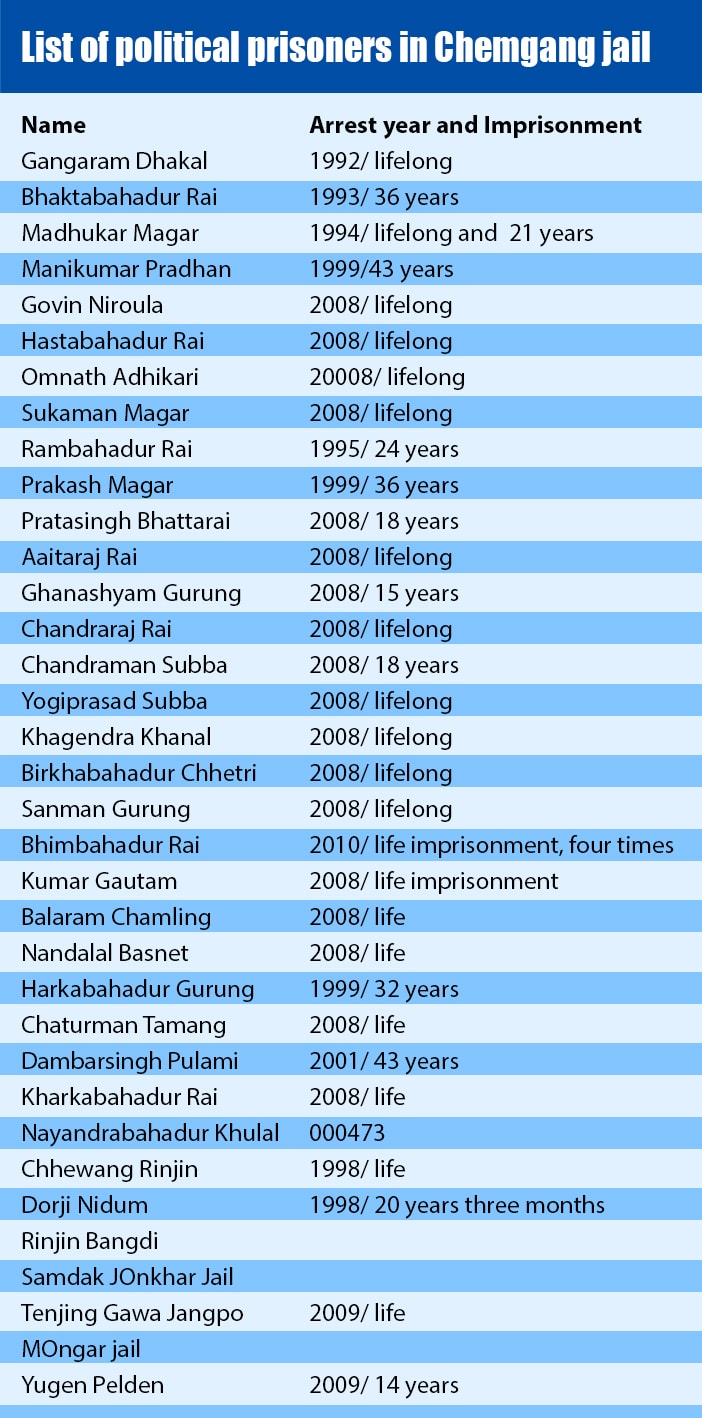

Majority of Nepali-speaking Bhutanese nationals who were forcefully evicted from the country since 1990 have now settled in various countries in the world after spending two decades of refugee lives. But many of their relatives have been imprisoned in Bhutan for 30 years. Over 30 political prisoners are housed at Chemgang jail.

Devendra Bhattarai | CIJ, Nepal

The Kakkadbhitta border point in Jhapa district in eastern Nepal lies about 50km away from Beldangi. And at a distance of 180km from Kakkadbhitta lies Jayagaun-Phuncholing border point separating Bhutan and India. A 150 km further distance away from Phuncholing lies Thimpu, the capital of Bhutan. And one has to cross Thimpu to reach the Chengbang prison. This is the nearly 380 km long route that parents of Bhtanese political prisoners have been traversing for years to meet their children languishing in Chengbang prison cells for years.

Standing on a queue of over two dozen relatives who took this long and difficult road to reach Phulcholing is one Dambarkumari Adhikari, 60. Dambarkumari was exiled through this same route 30 years ago, and now she is seen imploring to get a chance to meet her only son. The Bhutanese police administration responds sometimes but other times, turn a deaf ear. “Only by standing at that Phuncholing gate I feel like I am near to my son,” says Dambarkumari, remembering her son Omnath who was imprisoned in Chemgang jail 14 years ago. “It’s been about two years since I have received a permission to enter Bhutan due to the pandemic.”

This is about the Chemgang jail, the only central-level prison in Bhutan which is located seven kms away from capital Thimpu. Even the Internationl Red Cross is unaware about the conditions of army’s holding centres and a dozen other prisons. Because of the two-party agreement, the Red Cross cannot tour any other jails other than Chemgang, which itself has been banned from visiting for a decade.

Geeta mantras in the walls of jail

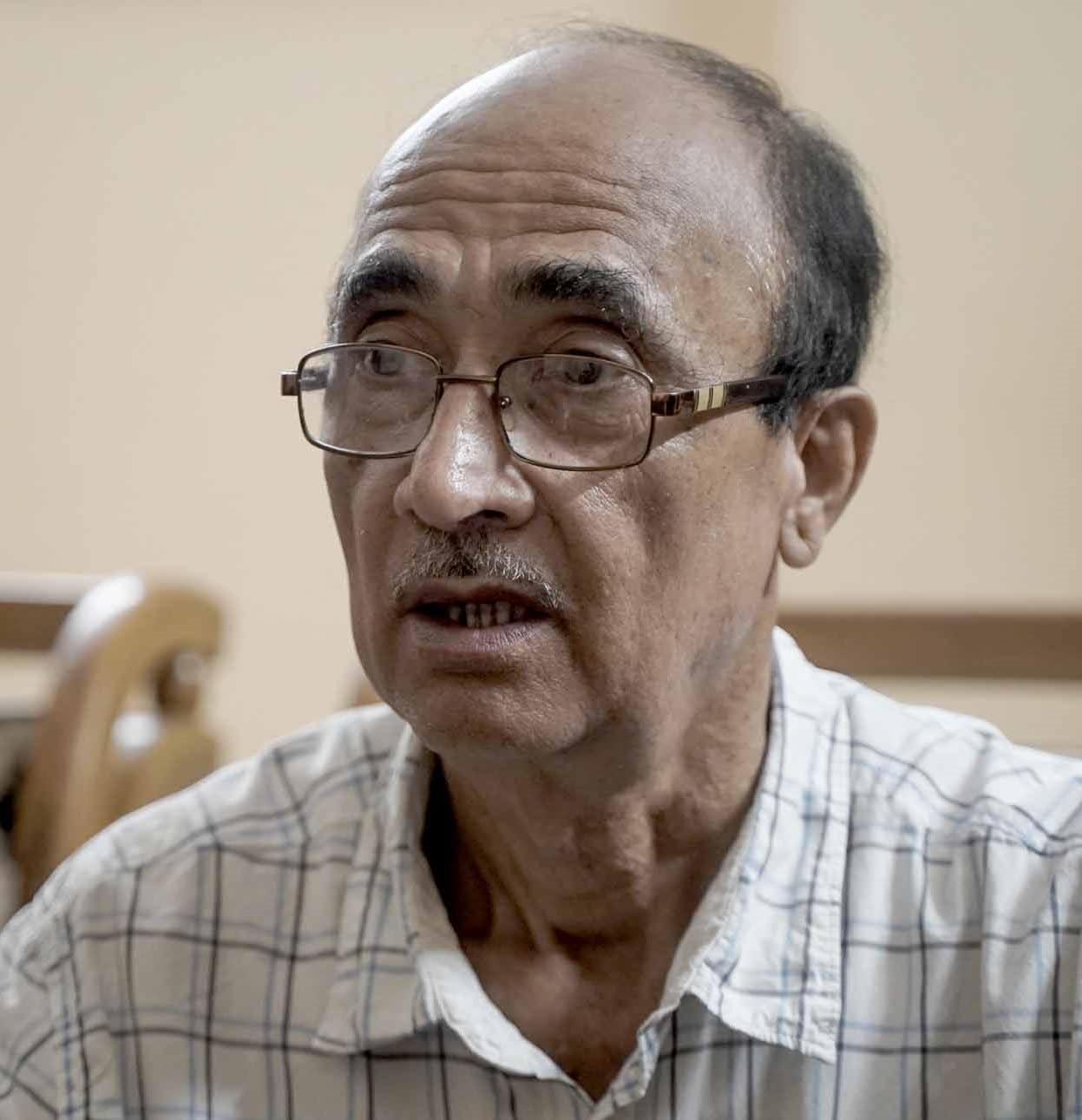

A former prisoner in Chemgang was was released two years ago hands over a few copies of photos to Teknath Rijal, a Bhutanese human rights activist. One of the pictures had a Geeta mantra embossed on a wall.

That prisoner did not just exchange pleasantries and his friends’ howabouts, but, with those lively photos, also made leader Rijal recall his own history of being imprisoned. Rijal had spent about a decade in different prisons in Bhutan and it was Rijal himself who had written those mantras on the walls in Chemgang jail. “When we were in prison, news of deaths in our families would come late. We would also receive news if any Nepali-speaking Bhutanese were beaten or killed,” Rijal recalls. “The mantras, upon which we would pray, were written to pay tribute to those demised souls, and to muster patience during contingent tragedies. I was emotional when I knew those mantras were intact, and prayed for the release of prisoners.”

Overcome by nostalgia, Rijal also recalled his friends during his time in prison—Gangaram Dhakal, Rambahadur Rai, Bhaktabahadur Rai, Harkabahadur Gurung, Prakash Magar, Chhewang Rinjin, etc, etc. What was surprising was that these friends were still imprisoned in Chemgang for nearly 30 years, and the world was unaware about their conditions.

The fact that over a hundred thousand Nepali-speaking Bhutanese (Lhotsampas) residing in southern Bhutan were ‘ethnically cleansed’ and came to Nepal as refugees in the 90s has now become history. Of the incomers, everyone is relocated to countries around the world, except for about 7000. Various agencies that arrived to determine ‘the refugees’ fate and identity’ such as UNHCR, World Food Program, and IOM have already returned. Amid this, a human rights report released annually by the US Foreign Ministry has started congratulating Bhutan since ‘the promotion of justice and human rights is satisfactory in Bhutan’. But many innocent people who were deemed ‘catalysts’ for bringing about political upheavel in Bhutan are languishing in prisons, about which neither Nepal has spoken not there is any voice raised in global forums.

Those who returned, after years of imprisonment

When Manbahadur Khaling Rai, a native of Samchi in Bhutan, arrived in the refugee camp of Damak, Jhapa to meet his family after staying in Chemgang jail for 21 years and three months, he was in for a shock. Neither his wife was in the camp, nor his children. His mother, younger brother and sister had already reached the Netherlands, and his three sons in the US. “When I came here in early 2017, the practice to register refugees was already discontinued. As someone who stayed so long at the jail, I could neither be listed as a refugee nor fly abroad,” said Manbahadur, who was at a hut in Beldangi Camp 3’s sector A-1, 43. “Now I only have a proof about my stay in Chemgang jail provided by ICRC, and nothing else.”

Manbahadur, who arrived in the refugee camp, travelled to Bhutan to meet his relatives for some urgent work. Upon entering Bhutan, he was detained and jailed on charges that he had ‘engaged in political activities in the past’. After then, he neither had his family with him, nor his identity.

Tekbahadur Magar, who is 50, was also seen wandering at Beldangi-2’s D4527 hut. He had arrived in Beldangi camp in the end of 2016 in search of his relatives after staying in Chemgang jail for 24 years. “My family had arrived in Nepal in early 1992 as refugees. After six months, I went to Bhutan to meet my aunt. I was detained all of a sudden, without any knowledge of why,” Tekbahadur recalls.

Tekbahadur, who was jailed when he was 20, was released when he was 44. His mother had paid him a visit once at the jail, but he could never meet his other relatives. When he arrived in Beldangi camp to meet his parents and siblings, all he could call his own was a dilapidated bamboo hut. His family members had already flown to the US. “Today, I am sad, and alone. I have no reason to continue living, I cannot say how I will live my life now on,” he said. “I was charged for treason. I had been to Bhutan to meet my aunt and to see the place I was born in, but I was detained. I have no idea how my life and those 24 years were spent, they just flew by.”

According to Tekbahadur, his friends Madhukar, Maniraj, Rambahadur, and Omnath, among others, are still at Chemgang jail. Around 25 other Nepali-speaking Bhutanese are also languishing there. When he was jailed, in the beginning, a 5kg iron rod was tied to his feet, and a chain around his body, he recalls. “It was a very difficult time and very painful,” he says, adding that only after the ICRC entered Bhutan did the situation for the imprisoned got better. “In the beginning, the pain inflicted was too intense,” he said. “During daytime, we would have to work in construction. We could never get to eat a neat, properly cooked rice. I don’t even want to remember that situation now.”

Tek Bahadur Magar and Gangalal Gurung

Dilkumar Rai, also from Samchi, arrived in Nepal in late 1990 as the Bhutan government’s ‘ethnic violence’ got unbearable. Dilkumar, who had tagged along with his father Jaharsingh and mother Saruma, was in Beldangi as a refugee, an identity he never imagined he would have to adopt. Later, when he went to Bhutan to meet his relatives in 1996, he was arrested from Sibsu and was imprisoned. He was also charged for being a ‘extremist-terrorist’, by the Bhutanese police, and was imprisoned for 20 years and 11 months in the Chemgang jail.

“When I was released in October 2017 and came to Beldangi camp, there was nobody I could call my own. But the relatives who had paid me a visit at the jail had started consulting about moving to the US, and I had bid them adieu saying they shouldn’t be waiting for me,” said Dilkumar, who is 57. “Today, I have nobody with me, I am here all alone, with nothing but a refugee certificate. And I don’t have anything to live for.”

Dilkumar, who was arrested in November 22, 1996, was imprisoned in Thimpu’s district jail for nearly a year and then in Chemgang. “When I was taken to Chemgang I was a prisoner number 253 according to ICRC registration. I returned after 21 years but those who have been there for about 30 years are still there. When I got out, over 30 political prisoners were still at Chemgang,” says Dilkumar, who is now a Pasteur at the Getesmani Church inside the camp. He recalled having to bear ‘unseen tortures’ even though the lives of the prisoners has eased a bit after the ICRC representatives started visiting Bhutan’s jails. “We’d have to work whatever the government ordered, mostly construction works. There was no place to relieve yourself in the night. Because the room would be locked from outside, we would have to relieve ourselves in a plastic bucket in the night and throw away the waste in the morning,” he said.

Dilkumar wants to raise the issue about the false assurance that ICRC representatives provide on their visit to the jail, saying, “If your family members are relocated to a third country and you come back after 50 years, even then we’d connect you with your family.” But there is not a single forum inside the camp today where Dilkumar could voice his concern, neither is there any mechanism that would take complaints.

Rudrabahadur Karki, who lives in Beldangi, Sector D 1, 88, is 65. In 1990, when he was living in Sarvang, Pinkhuwa, in Bhutan, the police arrested him and his brother Chandrabahadur. The allegations were the usual ‘incitement of violence and engagement in politics’. Rudrabahadur was released after being imprisoned in Sarvang district jail for 11 months. He got to meet his wife and children in Beldangi camp. But his brother could come to Nepal only after 18 months of imprisonment. Today, his brother’s family is resettled in the US, but Rudrabahadur is spending a ‘lone life’ in the camp. “My son, daughter and wife are now in Australia, and one another son in the US,” Rudra shared. “When I was processing to go abroad, my old mother was sick, and she wanted to breathe her last in Nepal. Hence, I stayed back, for my mother; later, when the process to move abroad was ongoing, I was accused of engaging in quarrels. At the same time, my family members moved abroad and I was left behind, alone.”

A father and his three sons together in the jail

Mangaldhoj Subba, a 74-year-old native of Dagana, Bhutan, has a similarly painful story to share. He was detained from Mirchula in mid-1990, together with his three sons. “There was no other reason. The police started beating us up, saying, ‘You are engaged in party activities’. Some died right in front of my eyes due to the police’s beatings. I was compelled to say, ‘Yes, I was engaged’, to save myself,” Mangaldhoj said. “My sons Dhanaraj, Dhanbahadur and Ranabahadur were also imprisoned together with me.”

His eldest son Dhanaraj was released within 10 months, and Mangaldhoj in 8 years. His other sons were ‘granted amnesty’ after 8 and a half yeaers. “We came to Nepal as refugees, and after then my sons and families have already moved abroad. I have stayed back,” he says. “I want to go back to Dagana.”

Shantiram Acharya, another refugee from Dagana, came to Nepal in June, 2014 after spending seven years in Chemgang jail. Acharya had first come to Beldangi in 1992 after ethnic violence against Lhotsampas ensued. But some of his relatives were left behind. “I went to meet my maternal uncle in January, 2007. And I was imprisoned with a false political charge in Chemgang,” Shantiram recalls. “When I returned back to Nepal, none of my relatives, including my mother, was here.”

Some relatives who went to meet Shantiram in prison told him about the possibility to move to a third country. “I told them that I could die here, so they’d better decide for themselves,” he remembers. “And my relatives indeed had moved abroad when I came here. I was weak with cardio diseases and depression. Even today, I can’t hold back my tears when I think of my past and my future. There is no way out.”

Amid his dilemma and tensions, Shantiram has one concern—like one of Dilkumar, who spend 21 years in jail. “Representatives from ICRC met me four times in Bhutan’s jail, other officials from UNHCR and IOM did too,” he said. “In all of the meetings, they assured me that I would get to meet my family upon my release. If I asked this question today, they reply, ‘This is not under our control.’ Why then did they took our relatives abroad? And why were we left stranded here?”

Those who keep waiting for their sons

Near the Bange Chautari in Beldangi lies ‘Refugee Mother’s’ home. If anyone from ICRC or UNHCR has to ask anything about issues of refugees, they remember the ‘refugee mother’—as a focal person.

Dambarkumari Adhikari, who was born and raised in Dagana, came to Nepal in April, 1992, her two children, Omnath aged six years and two-and-half year old Dhanmaya, in tow. She had migrated after the smart among her villagers started leaving the village, saying, ‘The revolution is on’, with her orphaned children. She raised her children and gave them education enduring much hardship and taking grant for refugee quota. Much later, in 2008 March, her son Omnath was among the 11 refugees who had travelled to Bhutan, all of whom were detained from Samjonkhar border in Bhutan.

And all of them are still imprisoned in Chemgang for life. They were all charged with ‘treason and political terrorism’; none of them know why they were enduring life imprisonment. The 11 youths were Omnath Adhikari, Birkhabahadur Chhetri, Hastabahadur Rai, Sanman Gurung, Chaturman Tamang, Nandalal Basnet, Govinda Niraula, Aaitaraj Rai, Khagendra Khanal, Sukaman Magar and Kumar Gautam.

Dambarkumari continues to struggle with her own fate, having lost her husband and having to leave her country. Another mother Kalawati Magar, 57, who also lives in Beldangi camp, also remembers her son imprisoned in Chemgang. “We were evicted from Sarvang in 1992,” she says, “Later, in 2008, my son got detained when he travelled to Bhutan. I only knew about it after he imprisoned.” Kalawati and Dambarkumari have travelled together to Chemgang many times, to meet their beloved sons.

“We exchange pleasantries when we meet, I ask how he has been,” Kalawati said. “We don’t know till when he would have to stay in jail. He says there’s no imprisonment time assigned for him.” Kalawati, who lives with her husband Narabahadur and youngest son Sanjeev, had grown restless when her relatives started to fly abroad. “We hope that he will return and then we can fly abroad too, but it doesn’t seem likely soon,” she said. “I see him even in my dreams. His wife and daughters have already moved to the US but we are still waiting for him. We are afraid if we’d die without ever meeting our son again.”

When Dalbir Rai escaped from Gelefu in Bhutan and arrived in Nepal, his wife and two sons were with him. The eldest of his sons, Bhaktabahadur, has been languishing in Bhutanese prison for 28 years. “We are waiting for his return and then to move abroad,” Dalbir, who is 82 and has cancer in his right eye, said. “But will he ever return?” Dalbir’s another son Indrabahadur has reached Chemgang thrice to meet his brother. After seeing his brother and many others like him, Indrabahadur reckons that they will be released someday and then returns back.

In 1993 October 2, in an attempt to bill Bhaktabahadur’s arrest as ‘valid’, the Kuensel newspaper, which is a government mouthpiece, published a news article with the title, ‘Police arrests a wanted terrorist’, in its final page. The article accuses Bhaktabahadur of being involved in theft, slandering, and rape, labeling him a ‘terrorist’. Incidentally, the same edition of the newspaper carries a news piece titled ‘Home Minister hopeful about Nepal negotiation’. The piece states, ‘Bhutanese Minister of Home Lhonpo Dago Tsering is leading a three-member delegation to Kathmandu to discuss plans to identify people living at camps in Nepal’s eastern plains.’

Detained while going to sell betel nuts

Among those who were suddenly forced to leave Bhutan after the ethnic cleansing began was the family of Narabahadur Magar. “I arrived in Nepal in 1991, along with my parents, brother and sister-in-law, and my wife and children,” said Narbahadur, who lives in Beldangi, B 3, Hut number 255. “In Bhutan we had a betel nut garden, and to sell the produce, my brother Madhukar had returned to Bhutan in 1994, and he was detained then, and imprisoned. He is still at the jail.” At the time, Narabahadur had been to Syangja for construction works to make a living. When he returned to the camp, his relatives had already flown to the US. Narabahadur is now alone, and neither does he know about his brother’s conditions, nor is he in contact with his family members in the US.

Gangalal Gurung’s family had 9 members, including his parents, and siblings, when they arrived in Nepal in 1992. In 2008, his brother Sanman had set out to travel with friends. Gangalal didn’t know his whereabouts then. After a long time, he knew that Sanman and his friends had been imprisoned in Chemgang. “I took my father to visit Sanman with the help of ICRC,” he said. After then, his family members have flown abroad. “When I met my brother two years ago, he asked me to take him along to the third country. That’s why, I am waiting for him to return,” he said. “But before leaving my brother told me to not wait for him with a heavy heart.”

A punishment of 43 years?

The Pulami family, which left Bhutan in 1991 for Beldangi camp, suffered deaths in the family quickly afterwards. The father was deceased at the camp and the mother in the US. Now two brothers in the family are in Bhutan, and two others in the US. “My brother Dambarsingh Pulami, however, is in Chemgang jail for 21 years,” Laxmi Pulami, who resides in Beldangi, said. “Because I don’t have a refugee certificate, I haven’t been able to go and meet my brother in Chemgang.”

Bhutan doesn’t determine an official imprisonment duration, and as such, many inmates are facing ‘life imprisonment. One Bhimbahadur Rai has been ordered life imprisonment four times. Even though the duration of life imprisonment is 15 years generally, the charge sheet against Dambarsingh Pulami mentions a 43-year imprisonment. Another inmate Manikumar Pradhan is also facing a 43-year long imprisonment, according to a list provided by Bhutan Human Right Watch and the Campaign to Release Bhutanese Political Prisoners.

Dambar Pulami, who is in Chemgang jail, is 58. His wife Sabitra, son, daughters and daughter-in-law all have domiciled in the third countries. Dambar’s wife, Sabitra, who is now in the US’ Penssylvania state, said, “We were evicted from Sarvang in 1992 and resided in Timai in Jhapa. My husband went to Bhutan to eke out a living for the family as our sons were growing up. It was a betel nut business there. And then we suddenly heard the news that he was imprisoned in Chemgang.” Sabitra, who had relocated to the US with her husband’s suggestion, had met Dambar five times in Chemgang with the help of ICRC. She doesn’t know till when her husband would be in prison but has heard rumors that it is 43 years. “Even if it’s just for the future of our children, he should be coming abroad,” said 55-year-old Sabitra over the phone. “Since we arrived here in 2011, however, I haven’t received any news about him. I am praying that maybe we would get to meet one day in this lifetime.”

Narapati Khanal, 68, and Deumaya, 64, both of whom live in hut number 272 in Beldangi-2, have a similar story to tell. The Khanal family’s second son Khagendra was detained in Bhutain in 2008, along with Bhaktabahadur and Sanman. “My brother lives in Chemgang’s block 4, and I and my father have gone to meet him a number of times,” said Umadevi Khanal, Khagendra’s sister. “On our visits he suggests us to move abroad, leaving his certificate and documents at the camp. But our mother doesn’t want to move anywhere until he arrives.” Two of the Khanal couple’s other sons have relocated to Australia and Canada.

Even though the prison provides lodging facility for four nights and three days, the relatives and their inmates can’t come into contact often. “Our mobile phones and bags are stored near the jail’s gate. We can’t take cooked food inside,” Umadevi said. “But we can’t see how the inmates are living. They are taken to the guest houses where we are located and we can spend a few days with them there.”

Teknath’s friend is still in prison

When Teknath Rijal, the rights activist and leader, was at Chemgang jail 24 years ago, he had a friend called Gangaram Dhakal. Dhakal is still in prison. Gangaram’s sister Tulasha Rimal said she often visits him. She recalled her brother of saying, “This is a life imprisonment. But we need to endure it not only for this life but a generation or two will have to as well. It’s not only me, there are 16 people here who have been enduring the same level of punishment.” Even though the punishment is stated life imprisonment, neither the brother nor sister could ascertain for how long he would have to stay behind the bars.

(Monks who turned protestors in eastern Bhutan have also been imprisoned at this jail)

Rabuna (military) jail

Prem Rai

Madhulal Budhathoki

Lokbahadur Ghale

Ramlal Rawat

Kumar Rai

Bishnu Rai

Shabahadur Gurung

Kinley Gyaltsen

MB Bhujel

Loknath Acharya (2014)

“He was detained at 22, and now he is 52,” said Tulasha, who was seen in Sector C-1, hut number 127 in Beldangi 2. “People like Tekbahadur, Dilkumar and others–whom I used to see while going to visit my brother—have already returned back. But as for my brother, it’s not certain how long he’d have to stay for.” Following the political upheavel of the 90s in southern Bhutan, the police administration had started ‘keeping a watch’ at certain villagers who were deemed smart. After they knew that the police was trying to arrest Gangaram Dhakal, son of Muktinath, the family fleed the village overnight in the summer of 92.

“I was 14 then. We were a family of 8 and all of us fled. We had reached Asam border in Baghmara through Bamjandanda in Bhutan,” Tulasha recalled those distant days. “We took shelter at a certain Luitel man for three weeks. For some money, we wanted to sell cows which we had taken with us. The Luitel family kept the cows but on credit. And then we arrived in Nepal via Siliguri.”

Gangaram Khanal, the eldest son the Khanal family, who had entered Nepal in 1992 and started to live first in Maidhar and then in Beldangi, went to Baghmara, Bhutan that same year to settle some business. It was only much later that the fact Gangaram had been to Sure via Baghmara and was arrested while residing at a friend’s place. “There’s hearsay that he was first in a house that was like a tunnel for the first six months of his arrest. And that he would be fed leftover food,” Tulasha said. “Of those who had come to Nepal, my parents are already dead, and two brothers are in America and Canada each. Sisters are also in America and Canada. It is only me who pays a visit to imprisoned brother.”

When she recalled all this, Tulasha was bursting out in tears. Her two daughters watching their mother cry looked as if they were full of request for her not to cry. “What is this life, didi?” I asked Tulasha before bidding adieu from the camp. “Life? It’s unbearable to recall! Everything is a mess, be it family or my heart,” she said. “I don’t have an ounce of hope that my family would get together again and be happy. In truth, it is only those like us who have few option that have to be stranded in a refugee camp. Life is just about that, bhai.”

More shattering than her reply was her wailing cry, echoing in the distance.

‘Fourteen years, and I’m still waiting for my son’

Dambarkumari Adhikari, Beldangi camp

My entire family was born and raised in Dagana, Bhutan. It was the summer of 1992 when the more aware villagers began to leave the village, proclaiming that a revolution was on the way. I, too, had to leave with my small fatherless children. My son Omnath was six years old at the time, and my daughter Dhanmaya was one and a half.

Life in the refugee camp was difficult. I raised my children on the rations we were given, doing my best to educate them. I had finally begun to believe that better days were on their way when my son, who was twenty-one years old at the time, left the camp to visit his ancestor’s place only to be imprisoned there.

My son Omnath Adhikari has been imprisoned for fourteen years. The Saptarangi FM here announced in 2008 (Fagun) that eleven Bhutanese boys had been apprehended on the Samdrup Jongkhar border. Later in Kartik, I went to the Damak Red Cross office to inquire about my son’s arrest and current situation. However, the officers present stated, “We don’t know anything about your son. If you want to visit Bhutan, you can do so on your own dime.” So I paid my own way to Funcholing-Jayagaun, but the police at the border there said no one named Omnath had been arrested so far. “I came here after hearing about the arrest on the radio; it was reported that 11 boys, including my son, were arrested. I’ll go to the jail once to find out what’s going on “I begged, only to be turned down right there in Funcholing. After being held there for three days, I finally received word from higher up in the command chain: “Omnath was arrested, and he’s still in jail.” They only let me go to the jail where he was imprisoned after that.

I felt like I could breathe again after meeting my son and other children there. They did not, however, allow me to spend the night with my son. I stayed at the guest house for two nights before returning. When I returned to Damak Camp, I informed everyone about our children’s arrests and where they were being held. We then began going to see our sons in turn. He’s my only son, whom I raised through adversity.

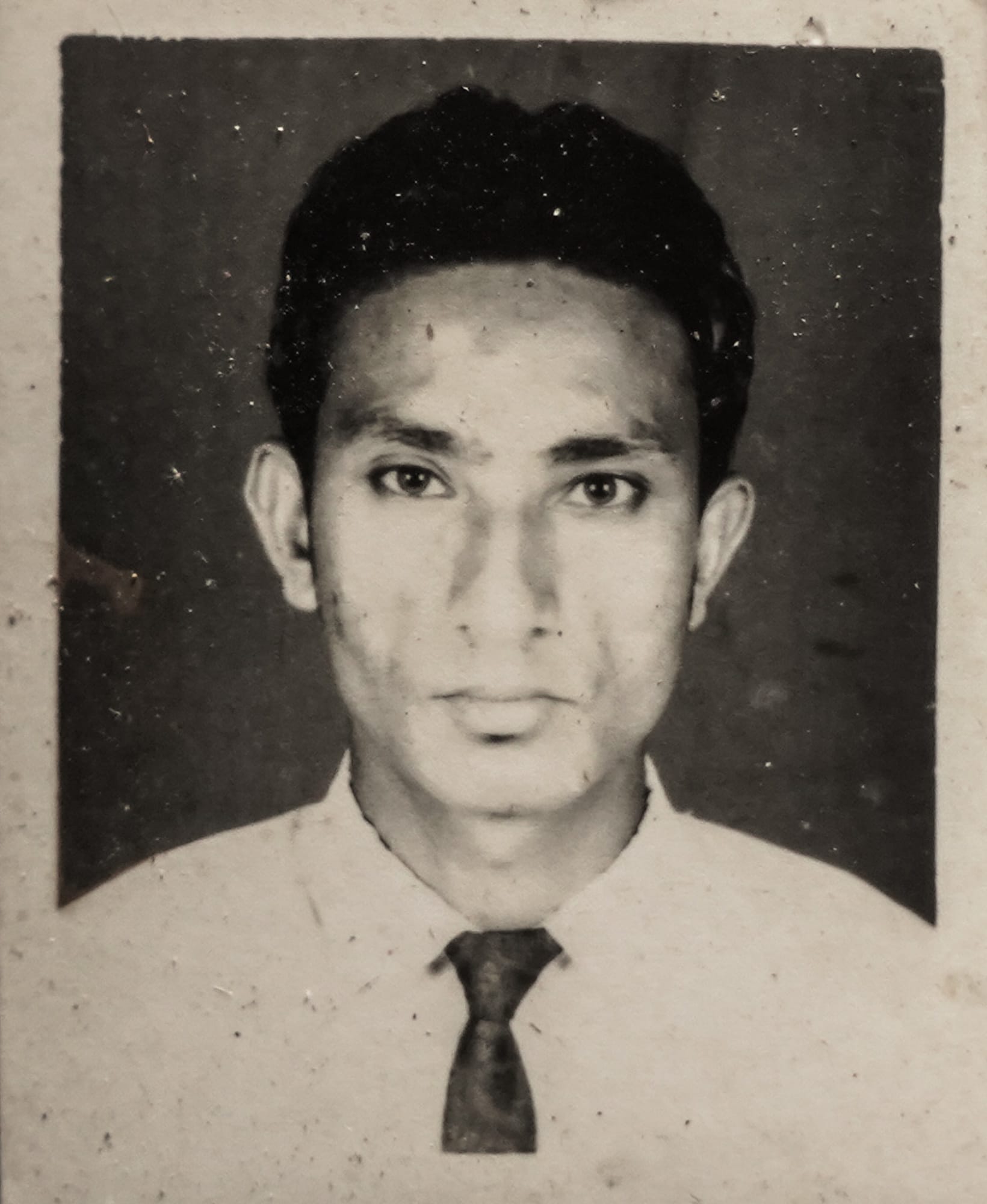

Omnath Adhikari

My love for him would not allow me to remain silent in the face of the situation. After informing the ICRC (International Red Cross) in Kathmandu, we began visiting them four times a month (three months apart). They began to reimburse us for our travel expenses. The police in Fulcholing had told us that if we came in groups of fifteen or sixteen, it would be easier for them to authorize passes, so we began going in groups of fifteen or sixteen. Even if we did all of that, some people would still be unable to obtain permission. We used to wait for two to three days at Funcholing before heading up to see our kids. This Bhadau 15, it will be two years since I first met my son in prison. All cross-border travel has been halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This Bhadau 15, it will be two years since I first met my son in prison. All cross-border travel has been halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite the fact that I was able to meet my son in jail, I am not at peace on the inside. I recall wading into a flooded river with my fatherless children in the hopes of surviving. We lived, but what is the point of a life like this? I now believe that leaving Bhutan was a mistake. Bhutan’s soil appears to have eventually drawn my son. For some, the decision to leave may have been well-informed, but it was not for me. I never found out why or how my son returned to Bhutan. He told me he was going to Goldap to play football because he was a football player. He had said he would return the next day for Bhaitika. I learned that my son, who had fled in Kartik, had been arrested in Bhutan in Fagun, and that he had been detained by the Bhutanese authorities.

When I arrive, the kids in the jail swarm around me like bees around a hive. Not only am I my son’s mother, but I am also everyone else’s. We’re both fish in the same pond. I’m saddened whenever I see a face there. I take a look at another one, and it makes me sad as well. That is unbearable to me. I bring clothes for some people and food for others. I go there with the intention of staying for two or three days and talking to my son about a variety of topics. But, as I caress my son, I’m not aware of how quickly time passes. If no one comes to see one of the children, I go to them and ask how they are. Because many of their families have already relocated to the United States or the United Kingdom, I am “Dambar Kumari Aama” for all of them. According to the information we have, twenty people have left the Beldangi camp. Three of them are missing, and their whereabouts are unknown. Loknath Acharya, Kulbahadur Basnet, and Hengum Dukpa’s whereabouts are unknown to those I know. Later, we learned that Loknath Acharya had left the camp in 2014 to go to Siligudhi to buy medicines for his parents, only to be arrested and deported to Bhutan. We still don’t know where he is or how he is doing. His mother and wife have already moved to a foreign country.

This is how fourteen years have passed in the hope that my son will return. The only way I can console myself is to think about other parents’ children who are serving time for twenty-eight to thirty years, and the possibility that if I live long enough, I’ll meet him. It would bring me peace to know what his fault is and what his punishment will be. I’m not sure if he’s alive or not now that COVID-19 has imposed a lockdown. Unable to sit and wait for him, I considered traveling to Australia, where my son-in-law lives, but the lockdown has put a halt to all plans. I’m here with my daughter and grandson.

Life appears to be like water on a Taro leaf; bend here and it spills. It spills again if you bend there. My son is my only source of hope and assurance. I’ll wait until I can’t.

——————-

“Born and raised in Bhutan, chased away to Jayagaun”

Tilak Katuwal (66)

Tilak Katuwal was born and raised in the Bhutanese town of Pana. He began working in Bhutan Government Public Transport, Funcholing, after completing his matriculation in 1975. He wanted to change his service, so when the opportunity arose, he began working for the Forest Department. He also traveled to Kharsang, India, to train as a Forest Officer.

Bhutan was peaceful at the time, according to Tilak, and he was on good terms with the government. The bad times began in the 1990s. Bhutan developed a policy to prevent “outsiders” from entering the country. The policy made life difficult for Bhutan’s Nepali-speaking population. There was peaceful opposition to the policy. At the time, Teknath Rijal was the Councilor for South Bhutan. Rijal was imprisoned for pleading to Bhutan’s King, Jigme Singe, that “Nepali-speaking people were being placed in a difficult situation.” As the Lhotsampa’s voice was silenced, anger grew, and protests erupted across Bhutan, which were quelled by the government. The general public was subjected to lethal attacks.

Tilak was in Europe (Norway) at the time for a one-year training program sent by the Bhutanese government. He returned to Bhutan near the end of 1989. “But when I returned, I found myself without a job; there were riots in the villages, and people were fleeing. “The government had put my name on the list of defectors,” Tilak, who was discovered in Jayagaun, India, recalls. “I requested the government many times saying that I was not at fault.” They denied and told me to leave the country, as all of my family had done, which is why I quit my job and started living in Jayagaun.”

Tilak had two children, one in Funcholing and the other in Thimpu. But he didn’t fight back. Accepting whatever fate had in store for him, he left the place where he was born and earned a living. Tilak currently resides in Jayagaun with his 98-year-old father, Ganga Bahadur Katuwal.

As far as Tilak is aware, it was a strategic plan to rid Bhutan of Nepali-speaking people (Lhotsampa). The government desired “ethnic cleansing,” and the refugee crisis arose as a result of their failure to do so. Those who left Bhutan after that would never be able to return, while those who stayed lived under government rule.

Tilak, who lives on the Bhutan-India border, believes that India has been protecting Bhutan in the same way that India “cleared” Doklam by taking up arms, and that Bhutan did not even have to fight in the Doklam issue. India is in charge of Bhutan’s borders with China. And the international community pays attention to what India says.

According to his understanding, the Bhutanese refugee crisis is handled in the same way that India has final say in Bhutan’s affairs. “Nepal is powerless to intervene in Bhutan’s affairs. It is politically ineffective. “Nepal cannot also take up the refugees’ issue on a global scale,” Tilak says, “so what should be done with the six to seven thousand elderly and children in refugee camps in eastern Nepal?” I believe it is impossible to return them to Bhutan. Those who can will go abroad, while those who cannot will maybe remain.”

——————-

“There were also those who were beaten to death”

Brahmalal Adhikari, USA

Brahmalal Adhikari, who was born in Gelephu, Bhutan 59 years ago, now lives in Iowa, United States after being listed on the refugees relocation program. Brahmalal and other villagers were involved in cattle rearing when he was in Gelephu. They would travel back and forth across the border in India to sell or graze their cattle in Assam’s Deusire (Meche settlement).

When the Bhutan government began their cruelty against Nepali-speaking people in South Bhutan in the early 1990s through false accusations and incrimination, the Adhikari family was also exiled on the grounds that they held dual citizenship (of Bhutan and India). Brahmalal was imprisoned for four months in Gelephu jail in the early 1990s on charges of “involvement in political activities” before being exiled. At the time, Adhikari was aware of the hangings of Khadgananda HUmagain and Tikaram Dhimal in military custody in Gelephu, as well as Ratna Biwsokarma and Khadga Bahadur Magar in Lodrai jail. Gangaram Rai was beaten in custody in Gelephu and died as a result of his injuries soon after being released, whereas the police-administration threw the body of HB Sapkota in 4 Kilo after he was beaten to death in Thimpu jail. Dharmaraj Gurung was also beaten to death in Damphu, Tsirang.

According to Tsering Ongda, the only lawyer involved in these types of arrests, imprisonments, and punishments was Tsering Ongda, who represented both the plaintiffs and defendants. Ongda was also the then-Home Secretary, who served as both the plaintiff’s and defendant’s lawyer for all prisoners, including state prisoners, and set punishments himself. “We arrived in Timai, eastern Nepal, in early 1992, after being exiled. Later, in February 1993, when we went to Meche settlement in Assam to raise money by selling our livestock that were kept there, I was arrested by the Indian police in Kokrajhar, Assam and handed over to Bhutan,” Brahmalal explained over the phone. “Then, I was imprisoned in Zhemgang for sixteen years, the previous nine of which I was with Leader Teknath Rijal.”” Adhikari arrived in the United States in mid-2017, near the end of the Bhutanese refugee relocation program to a third country.

Biswonath Chhetri, like Brahmalal, was imprisoned for a long time and is now in the United States with Devdatt Sharma and Bhakti Bhandari. Bhutanese political activists Ratan Gajmer, IB Chhetri, Jogen Gajmer, and Sushil Pokhrel, on the other hand, live in Australia.

__

“We don’t have the permission to inspect Bhutan’s jails,”- ICRC

Following the burgeoning protests in the 1990s, the Bhutan government began exiling Nepali-speaking people, particularly in South Bhutan. In response to the uprising, over one lakh Bhutanese citizens crossed 200 kilometers of Indian territory to seek refuge in eastern Nepal. The International Red Cross (ICRC) entered Bhutan in 1994, in the midst of a situation characterized by the Bhutan government’s terror on its citizens, extra-judicial detentions, disappearances, and killings. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) delegation was only permitted to visit Bhutan’s central jail in Zhemgang and pressurize the government to provide state prisoners with adequate food, shelter, and clothing. The International Committee of the Red Cross was granted permission to enter Bhutan on the condition that it only inspect state prisoners detained under Bhutan’s National Security Act.

Following the burgeoning protests in the 1990s, the Bhutan government began exiling Nepali-speaking people, particularly in South Bhutan. In response to the uprising, over one lakh Bhutanese citizens crossed 200 kilometers of Indian territory to seek refuge in eastern Nepal. The International Red Cross (ICRC) entered Bhutan in 1994, in the midst of a situation characterized by the Bhutan government’s terror on its citizens, extra-judicial detentions, disappearances, and killings. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) delegation was only permitted to visit Bhutan’s central jail in Zhemgang and pressurize the government to provide state prisoners with adequate food, shelter, and clothing. The International Committee of the Red Cross was granted permission to enter Bhutan on the condition that it only inspect state prisoners detained under Bhutan’s National Security Act.

After the International Committee of the Red Cross entered Bhutan, there was a decrease in the number of inmates who testified about torture and extrajudicial activities. Under the ICRC’s initiative, state prisoners in custody were also allowed up to four family visits per year. Family members of inmates at Chengang jail continue to praise this aspect of the ICRC’s work. The International Committee of the Red Cross has also been involved in the jail’s cleanliness, healthcare, and guesthouse for visitors (conjugal ward). However, since 2012, the Bhutanese government has stopped granting the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) permission for prison visits. According to Mira Rana, Liaison Officer for the Bhutan issue at the ICRC’s Nepal office, the Bhutan government informed the ICRC that because guidelines inside the jail, provisions for health and security were already in place due to agencies such as the ICRC’s insistence, ICRC visits were no longer required. In 1993, Bhutan’s government and the International Committee of the Red Cross reached an “agreement” outlining the terms under which visits would be permitted. The ICRC had only been permitted to visit under this “agreement” for ten years. The “agreement,” which was supposed to be renewed every year, was not renewed after 2012.

One condition that remains intact in the agreement with the ICRC is the right of inmates’ family members to visit them. When family members in Nepalese refugee camps request visits from the ICRC office in Kathmandu, the Kathmandu office contacts its Delhi office, which then contacts its Thimpu office. Permissions are granted only after an investigation of the inmates and their family members.

Yan Miskok, Deputy-head of the Regional Delegation in Delhi that oversees the Bhutan issue on behalf of the Red Cross International Committee, provided the following written response:

We apologize and want to make it clear that the International Red Cross (ICRC) is not in a position to easily inspect Bhutan’s jails. The main goal of the ICRC is to reinforce custodies where they are present, to continue and reinforce family visits, and to maintain a general respect for legal protection. In the midst of the pandemic, the ICRC has provided guidelines and distributed solutions for effective operations in an effort to maintain dialogue with relevant authorities regarding the general management of custodies.

Concerning the information gathered by the ICRC about the prisoners housed in these facilities, it can only be shared with the Detention Authority and no one else. As per the agreement, such information cannot be shared without prior permission from the jail authority.

Concerning the personal information of inmates collected in advance by the ICRC, it should be noted that the ICRC is strictly governed by its statistics protection rules. In general, the ICRC tries to avoid causing harm to the concerned person or their family members by disclosing this information to a third party.

In terms of statistics, we request that you use publicly available statistics; otherwise, we will only be able to inform the relevant authority about the subject.